It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Showing posts with label Ludwig van Beethoven. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ludwig van Beethoven. Show all posts

Monday, January 5, 2026

Friday, October 3, 2025

Why Did the Great Composers Rewrite Beethoven?

by Emily E. Hogstad

Romantic Era composers had a unique relationship with Ludwig van Beethoven. The man and his music cast a massive shadow over the nineteenth century, especially when it came to orchestral music.

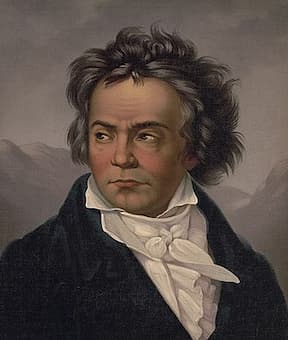

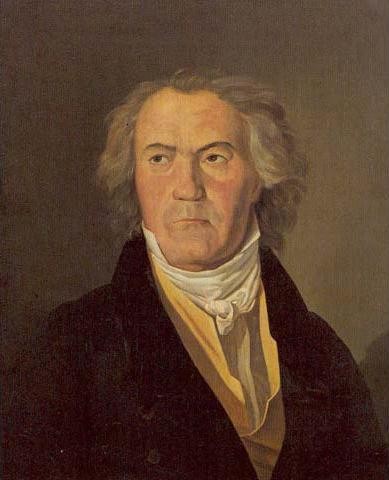

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Ludwig van Beethoven, ca 1804–1805 (Vienna Museum)

The Beethoven works that loomed the largest were his nine symphonies, especially the Third (composed between 1802 and 1804) and the Ninth (composed between 1822 and 1824).

These works were so revolutionary that many composers found it difficult to write orchestral works after them.

Brahms, for instance, knew that any symphony he’d write would inevitably be compared to Beethoven’s. He struggled for over twenty years to write his first symphony. And even after all that effort, he still couldn’t escape Beethoven’s shadow: Brahms’s First quickly earned the nickname “Beethoven’s Tenth.”

Interestingly, one of the surprising ways that composers engaged with Beethoven’s towering legacy was by completely – and creatively – reimagining his works.

Today, we’re looking at three major composers who rewrote the Beethoven symphonies.

Franz Liszt Rewrites the Symphonies for Piano

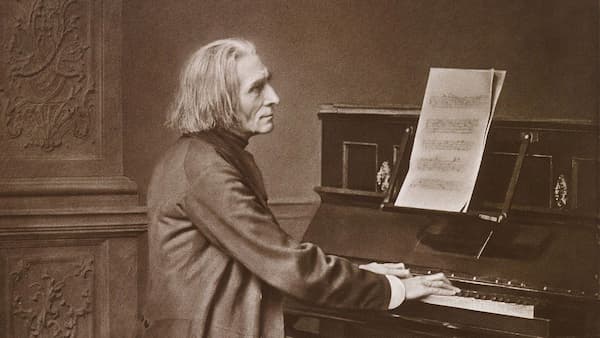

Carbon print circa 1869 by photographer Franz Hanfstaengl

Franz Liszt was born in 1811 and apparently met Beethoven as a young prodigy shortly before Beethoven died in 1827.

At the beginning of his career as a daredevil virtuoso pianist, Liszt would transcribe the fifth, sixth, and seventh symphonies for piano. Decades later, he would finally complete the set.

These transcriptions have a frenetic brilliance to them that makes for gripping listening.

In the 1960s, Glenn Gould became the first pianist to record the transcripts of the Fifth and Sixth symphonies. Gould described them before a radio broadcast:

According to a rather touching paragraph in Grove’s Dictionary, these keyboard extravaganzas were intended for his own use in towns which could boast no municipal orchestra, and before audiences which were otherwise without access to the symphonic milestones of Beethoven.

We have no such access problem these days, but Liszt’s transcription is much more than a tremolo-laden silent movie style period piece.

It’s not just remarkable as an archival curio, nor even as a typically Lisztian object lesson in the deployment of pianistic sonority, for even while it maintains an almost puritanical fidelity to the original text, it captures, I think, Liszt’s view of Beethoven, and, by implication, the attitude of the Romantic Age toward the classicist who unleashed romanticism.

In his pre-performance remarks, Gould verbalised a couple of reasons for Liszt to take on the project: to increase the symphonies’ accessibility in cities without orchestras, and to capture nineteenth-century ideas about the works for future generations.

Wagner Takes on Beethoven

Richard Wagner

Composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) was just a boy when Beethoven died.

He had recently fallen in love with music and was devastated by the loss. He later wrote about meeting Beethoven in his dreams, then awakening in tears.

In 1831, when he was still in his teens, Wagner made a transcription of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for solo piano and voices. (Liszt had circumvented the difficulty of transcribing the choral part in the ninth by adding a second piano to his transcription.)

Wagner wrote of his attraction to the symphony:

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony became the mystical goal of all my strange thoughts and desires about music… It was considered the ‘non plus ultra’ of all that was fantastic and incomprehensible, and this was quite enough to rouse in me a passionate desire to study this mysterious work.

However, unlike Liszt, Wagner didn’t stop at a piano transcription.

In 1846, when he was working as a music director in Dresden, he mounted a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth. He prepared the local population for the performance by writing articles in the local newspaper.

He also altered the score. He believed that Beethoven wrote particular passages in certain ways because of his deafness or the limitations of earlier, more primitive instruments.

For instance, in bars 53-68 of the Scherzo, Wagner doubled a woodwind passage with brass.

Wagner also addressed the tempos of the symphony, encouraging musicians to discard the metronome markings that Beethoven had left behind, and taking the final two movements at almost half the speed of what Beethoven had indicated in the score.

(For a long time, conventional wisdom suggested that Beethoven’s deafness had made him incapable of judging the effects of the metronome markings, which many interpreters believed were too fast.)

Here’s a performance close to Beethoven’s stated metronome mark, as played by the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra under Nicholas McGegan:

And here’s a Wagnerian tempo, as typified by the Vienna Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler:

The difference is stark.

Interestingly, Wagner also moved the chorus from in front of the orchestra to behind it: an arrangement that has been adopted in modern performances today.

Gustav Mahler Takes on Beethoven

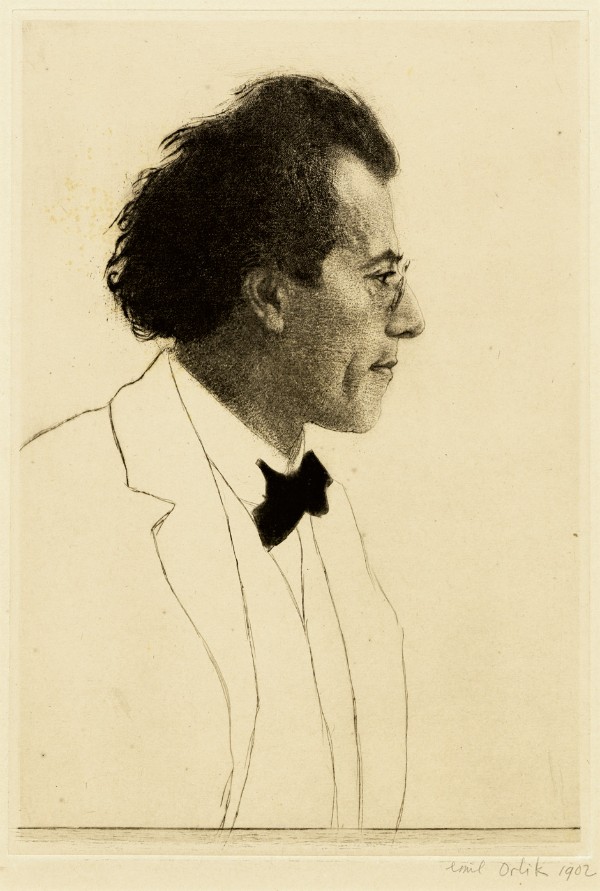

Gustav Mahler, 1902

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) agreed with many of Wagner’s interpretive ideas. He was also in a position to put them into action after he became the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic in 1898.

Mahler decided he wanted to modernise Beethoven’s symphonies to sound better in larger modern concert halls. Accordingly, he set about tinkering with the scores of all of them, save the Fourth.

Conductor Michael Francis, who has conducted a 2024 recording of these versions, says:

Mahler was concerned that in the turn of the 20th century that Beethoven’s classical language had lost some of the power. You think about some of the pieces that Strauss is writing; think of the pieces that Mahler was writing. So these are huge, big pieces, and he wanted Beethoven’s strength to be heard.

In order to create a bigger sound, Mahler doubled the winds and horns and even added a timpani player and tuba player.

In February 1900, Mahler debuted his new version of Beethoven’s Ninth.

Audiences were scandalised. Purists claimed they were upset because they valued Beethoven’s original score so highly, but the entire hullabaloo was also a convenient outlet for raging Viennese anti-Semitism.

The outcry became so loud that Mahler was forced to write an explanatory note in the press about his choices!

Judge for yourself; here’s the version of the Ninth Symphony that was so controversial.

In 2024, we published an article looking at his changes to Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

In 2020, we did an interview with conductor Johannes Vogel about what it’s actually like to perform these Mahler adaptations.

And here’s critic Dave Hurwitz sharing his opinions about the Mahler reorchestrations:

Conclusion

Every composer has to reckon with the shadow of Beethoven.

These three composers – Liszt, Wagner, and Mahler – did so in an especially intriguing way: by rearranging and rewriting his music, all for their own unique reasons.

Liszt wanted to be able to share Beethoven’s works with a wider audience. Wagner wanted to better understand his composer idol and translate Beethoven’s intentions for a new generation. Mahler continued that same mission where Wagner left off.

Whether you appreciate their work or not, it’s undeniable that each of these men made major contributions to Beethoven’s legacy. In the process, they proved the symphonies’ relevance and timelessness.

Friday, August 29, 2025

Composer Emilie Mayer: Was She the Female Beethoven?

by Emily E. Hogstad

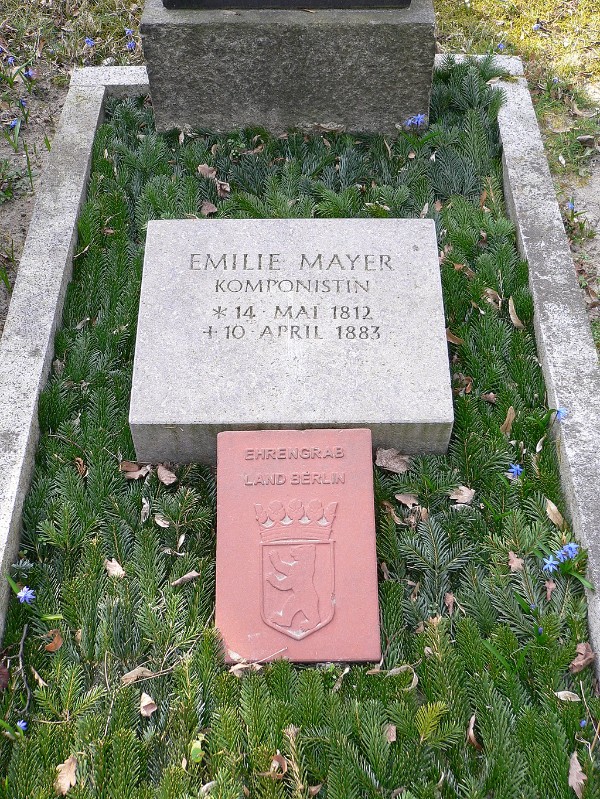

Emilie Mayer, sometimes referred to as the “female Beethoven,” was one of the most prolific composers of her generation.

Emilie Mayer

Mayer’s symphonies, chamber music, and piano works stand as testaments to both her talent and her determination to succeed in a male-dominated world.

Today, we’re looking at her gripping biography and how she made a hugely successful career for herself in her middle age, after enduring unimaginably painful personal loss.

Emilie Mayer’s Family

Emilie Mayer was born Emilie Luise Friderica Mayer on 14 May 1812. She was the third of five children and the eldest daughter.

The Mayers lived in the German town of Friedland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, roughly seventy kilometers from the Baltic Sea, where her father worked as an apothecary.

Tragedy struck the family a few years after Emilie’s birth, when her mother died. After her mother’s death, Emilie would have been expected to play the role of matriarch within the immediate family.

This may have been one reason why she never married…and one reason why she felt freer to become a composer.

Emilie Mayer’s Early Education

Emilie Mayer

It is believed that Emilie’s education was overseen by private tutors, as the local Latin school only accepted boys.

She began piano lessons at the age of five with a local organist named Carl Heinrich Ernst Driver.

She later wrote modestly, “After a few lessons… I composed variations, dances, little rondos, etc.” Driver was amused by his student’s precocity and helped notate these works for her.

Her father was thrilled by his daughter’s musical talent and supported her studies throughout her childhood.

Unexpected Tragedy Changes Everything

The defining event of Emilie’s life occurred in 1840, on the twenty-sixth anniversary of her mother’s burial, when her father shot and killed himself.

She dealt with her shock and grief by throwing herself into composing. But tragically, she suffered another major blow a few months later, when her teacher, Driver, also died.

Emilie was fast approaching thirty, without the economic protection a nineteenth-century husband would provide. Suddenly, she had to figure out what to do with the rest of her life, and how to make a living – and fast.

She decided to devote herself to music. Fortunately, her brothers supported the decision.

Moving to Szczecin

After her father’s affairs were settled, she moved to the city of Stettin (now known as Szczecin, Poland) where her younger sister and brother-in-law had moved after their marriage.

Women were barred from formally studying composition at most institutions of higher learning. The only option for most women who were interested in composing was private study with a tutor.

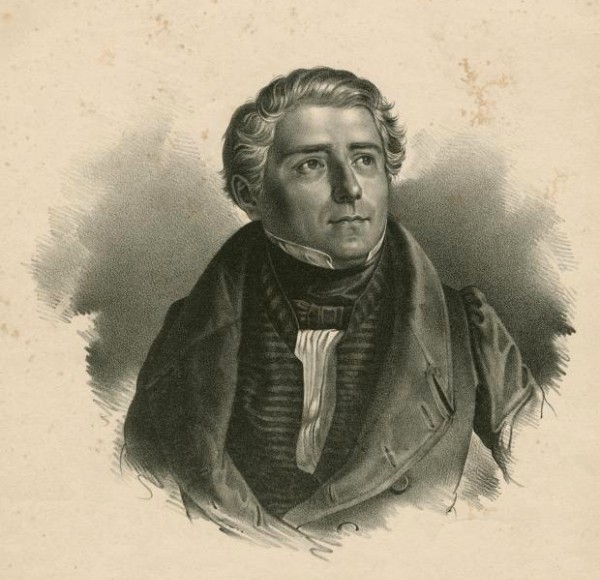

Carl Loewe

So she began taking private lessons from composer and conductor Carl Loewe, whose nickname was the “Schubert of North Germany.”

He was astonished by her natural ability, claiming that “such a God-given talent as hers had not been bestowed upon any other person he knew.”

He also famously commented: “You actually know nothing and everything at the same time! I shall be the gardener who grows your talent from a bud to a beautiful flower.”

The wording may have been patronising, but his heart was in the right place, as evidenced by the support and encouragement he gave her over the following years.

Studying with Loewe

During her apprenticeship with Loewe, she wrote her first two symphonies (No. 1 in C-minor and No. 2 in E-minor).

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 1

Because of his support and the support of the local music directors, Mayer had the opportunity to hear her orchestral works performed: an unusual opportunity for a woman composer of the era.

She incorporated what she learned into her next compositions for large ensembles.

She also began performing her chamber music at more and more private concerts and salons.

But there was only so much she could accomplish in Szczecin, and she became curious how far she could go if she relocated to a bigger city.

In 1847, on Loewe’s advice, she moved to Berlin – this time by herself, without any family.

Studying in Berlin

Adolf Bernard Marx

In Berlin, Emilie began studying fugue and double counterpoint with theorist and musicologist Adolf Bernard Marx.

Marx was a one-time friend of Felix Mendelssohn who had since feuded with him (and, in a fit of typically dramatic Romantic Era pique, destroyed their correspondence by throwing it into a river).

She also studied instrumentation with pioneering military bandmaster Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht.

Reviews of her scores soon began appearing in local music journals. At first, she submitted them under the name E. Mayer, where they were widely praised.

However, as soon as it became known that she was Emilie Mayer and not, say, Edward Mayer, reviewers’ attitudes grew more critical.

Publishing Her Music

Around this time, she set her mind on publishing her works.

To publish music in 1847 Berlin was a provocative step for a woman to take. Many women composers opted to keep their works private. To many, a woman publishing was seen as unseemly and immodest…as well as an implicit criticism of male relatives’ abilities to provide economically.

To grant perspective to Emilie’s decision, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’s family – also based in Berlin at the time – were notably cool on the idea of her publishing her works.

In 1846, the year before Mayer arrived in town, Hensel had gone against her family’s wishes and overseen the publication of a few of her hundreds of works.

In August 1846, Hensel wrote to a friend about pursuing publication:

I can truthfully say that I let it happen more than made it happen, and it is this in particular which cheers me… If [the publishers] want more from me, it should act as a stimulus to achieve. If the matter comes to an end, then I also won’t grieve, for I’m not ambitious.

Mayer, however, was ambitious. She was determined to “[make] it happen”…which it soon did.

Organising a Concert

Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, 1847

In the spring of 1850, Emilie began organising a concert consisting solely of her own works. The date was set for 21 April 1850.

The professional connections she’d been making paid off. Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, subsidised the costs of the performance and made free tickets available to the hand-picked audience.

The program ultimately included an overture, two symphonies, and her setting of Psalm 118 for chorus and orchestra, as well as chamber works including a string quartet and some works for solo piano.

Her teacher Wilhelm Wieprecht conducted.

Soon after, Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria, the Queen of Prussia, awarded her a gold medal of art.

The audience came away impressed. Famous critic Ludwig Rellstab wrote that her themes “flow smoothly through the securely defined realm of tonal colours, often with surprising elegance.”

A Blossoming Career

Over the following months, she would continue to organise concerts of her music. As a result, her output as a whole became increasingly acclaimed.

Her dramatic B-minor symphony, dating from 1851, with its bold Beethovenian gestures, became especially popular.

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 4

Loewe wrote of his student’s work, “The minor symphony by Miss Emilie Mayer is, in my deepest conviction, in any case an important and ingenious work of art with which the talented artist has enriched musical literature.”

Remarkably, Emilie would write a symphony annually during her time in Berlin, on top of her other compositions.

An International Career

Her productivity and self-promotion paid off. Soon her works were being performed in cities across Europe.

She traveled to Cologne, Munich, Leipzig, Halle, Brussels, Strasbourg, Dessau, and Lyon to oversee various performances.

She also became an honorary member of the Philharmonic Society in Munich, and, back home, started co-chairing the Berlin Opera Academy.

In 1856, she was invited by Archduchess Sophie, the mother of Emperor Franz Josef I, to perform her chamber music in Vienna, which she did. She was accompanied to Vienna by her brothers.

Lisztian Praise

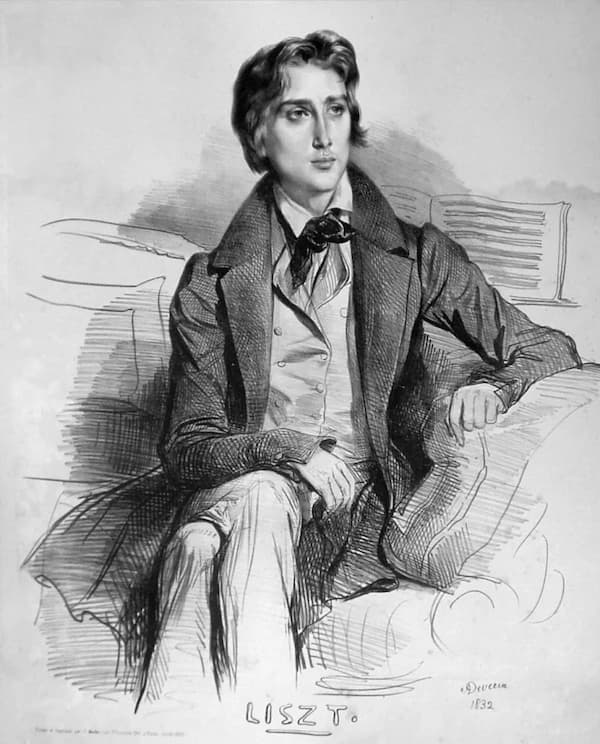

Franz Liszt

Ever scrappy and resourceful, she kept up the momentum by writing to Franz Liszt, the most famous musical celebrity of his day, asking if he would be interested in transcribing her D-minor String Quintet for piano. (Savvily, she had dedicated the piece to him.)

Emilie Mayer: String Quintet in D major (a similar work)

He turned her down because he didn’t want to transcribe a string quintet for piano, but he praised the work:

I received your excellent quintet in D minor, which you are so kind to dedicate to me, only when I returned to Weimar these days, and therefore I would like to apologise for the delay in my sincere thanks to you.

Reading this work has given me a lot of interest – and I hope to hear even more[…]

The impossibility of reproducing orchestral works and especially string quartets with their indispensable sound and color on the dry piano has been with me for a long time of all arrangements – Attempts averted.

So do not misinterpret it, dear composer, when I [decline] your kindly wish, to transfer your quintets for the piano forte…

Returning to Szczecin and Her Roots

In 1861, at the age of forty-nine, she moved back to Szczecin.

We don’t know exactly why, but it may have been to be closer to her family, or possibly due to health reasons. In any case, she moved in with her brother and his family.

She still composed, but, having written eight symphonies, turned her attention to mastering chamber music.

Historians are still assembling her output, but it appears that she wrote at least…

- Seven violin sonatas

- Eleven cello sonatas

- Eight piano trios

- Two piano quartets

- Seven string quartets

- Two string quintets

- Eight symphonies

- Seven overtures

- One piano concerto

- One unfinished Singspiel opera, Die Fischerin

Some scores were lost in World War II when libraries were bombed.

However, the scores to many of these works (some of them still handwritten) are available on IMSLP for free here.

Return to Berlin and Later Life

In 1876, Mayer moved back to Berlin. As her comeback piece, she wrote and presented her Faust overture, inspired by Goethe.

The work was a major success and marked two decades of triumph in the music industry.

Emilie Mayer died in Berlin on 10 April 1883 from pneumonia, a few weeks before her seventy-first birthday. She was buried at the Holy Trinity Church near Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel and her brother Felix.

She died unmarried. Without a husband or children to carry on her legacy, many of her works fell into obscurity, despite their high quality and popularity.

Emilie Mayer’s grave

With the increased interest in women composers nowadays, more and more modern people are discovering her works. A series of wonderful recordings have been produced over the past few years. Hopefully, we will see her music on programs more and more in the seasons to come.

For further reading on Mayer, here is a link to “The Lieder of Emilie Mayer”, a research paper by Stephanie Sadownik.

Friday, May 9, 2025

Finding a New Creative Path: Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto

by Maureen Buja

When he finally arrived in Vienna as a permanent resident in 1795, Beethoven fit into an interesting hiatus in the city’s music life. Mozart‘s recent death left a place open for a daring piano virtuoso and composer. In his first 10 years in the city, Beethoven wrote 20 of his 32 piano sonatas and 3 of his piano concertos—who better to show off his skills than himself?

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Ludwig van Beethoven, ca 1804–1805 (Vienna Museum)

Completed in 1803 and revised in 1804, Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto started with sketches as far back as 1796, and the first and second movements were completed around 1800. It was given its premiere with the composer at the keyboard on 5 April 1803 in a concert that included the Second Symphony and Christ on the Mount of Olives, his oratorio.

Beethoven was starting to have problems with his hearing as he approached this concerto, and this set him on his new creative path. Music, for him, became a dynamic process, rather than the filling in of architectural forms. One example of this can be seen in his 3rd Symphony, the Eroica, where the first theme isn’t as it is first stated but comes to define its form through the progress of the first movement.

The 3rd Piano Concerto falls between this new compositional method of the Eroica and his earlier Viennese style, when he was more concerned with establishing his name and credentials as a composer and performer.

If we look at just the first movement, we seem to be starting with a theme more intended for a symphonic movement, rather than a concerto movement. The orchestra gives the first statement of the theme, and Beethoven uses the orchestra to create motivic blocks that can be moved around as necessary. He plays with the different registers of the orchestra and inserts his ‘heavy beats on light places’ to play with the rhythms. His focus, however, is the soloist, and the piano is given a brilliant placement that foreshadows much of his later piano writing.

The repeat of the opening gives him the opportunity to play with the opening theme, but the following development is kept short. It’s the final section, with the Coda where the theme seems to really blossom and show its potential.

There’s so much in this work that gives us an indication of the unique way that Beethoven will progress – always challenging the norm, pressing forward with new ideas, and rethinking the usual to create the unusual.

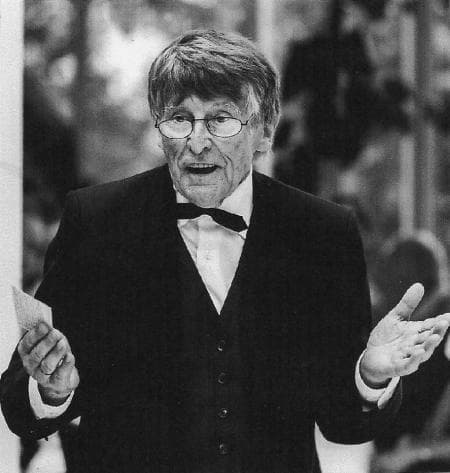

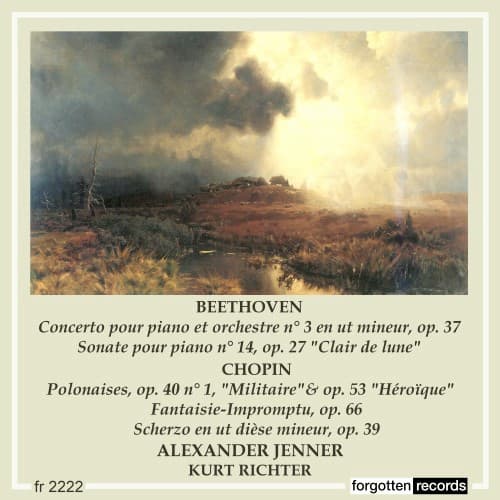

This recording was made in 1958, with Alexander Jenner as soloist under Kurt Richter leading the Symphony Orchestra of the Volksoper Vienna.

Alexander Jenner

Alexander Jenner (b. 1929) studied in Vienna and, upon graduation in 1949, was awarded the ‘Bösendorfer-Preisflügel’, a grand piano given to the best student of that year graduating from the Vienna State Academy of Music. In 1957, by unanimous jury vote, he was awarded first prize in the Rio de Janeiro Contest for Pianists. As a performer, in addition to the classics, he was active in the promotion of modern music, becoming the first Austrian pianist to perform George Gershwin’s two great piano works, the Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F in 1951; he also gave the premiere of Stravinsky’s Petrouchka for solo piano.

Kurt Dietmar Richter

Kurt Dietmar Richter was a German composer and conductor (1931–2019) who lived in Pilzen, Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. He received his musical training in Erfurt, where he fell under the influence of Paul Hindemith and, throughout his life, continued to promote modern music. In 1990, he founded the Berlin artist initiative die neue brücke.

Performed by

Alexander Jenner

Kurt Richter

Symphony Orchestra of the Volksoper Vienna

Recorded in 1958

Official Website

Friday, April 25, 2025

Ludwig von Beethoven “The Sounds of Silence”

by Georg Predota

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1818

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was the rising star on the Viennese music scene in the last decade of the 18th century. He made his name by showcasing his talents as a pianist, and he composed and performed piano sonatas of extreme technical difficulty. At the same time he composed music for a variety of musical ensemble and occasions. Ludwig van Beethoven needed to be busy, because he was a freelance musician. In fact, he was the first major composer in that city who did not depend on a fixed musical appointment. However, Beethoven had a dark secret. During his mid-20s, he gradually started to lose his hearing. At first, these periods of temporary hearing loss might not have caused him much concern, as he had suffered from a number of ailments, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and spells of fever since childhood. It seems that he noticed the first symptoms in 1796, or possibly somewhat earlier. In 1815, he told the English pianist Charles Neate that the cause of his hearing loss could be traced back to a quarrel he had with a singer in 1798.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2, No. 3

Beethoven, 1800-01

The story goes that a tenor was visiting Beethoven in his apartment. Apparently, they got into a heated argument and the tenor stormed out in a huff. Unexpectedly he returned and knocked on the door. Beethoven is said to have jumped up from the piano angrily to rush and open the door. However, his leg got stuck and he fell face down to the floor. This small accident was not the cause of Beethoven’s deafness, but it triggered a long and continuous hearing loss that would end in almost complete silence. Supposedly, Beethoven said about that particular fall, “I found myself deaf, and have been so ever since.” The hearing loss initially affected mostly his left ear, and as it grew worse Beethoven started to suffer from a severe form of tinnitus. The continued buzzing in his ear made it increasingly difficult to hear music or conversations, and it drove him to the brink of suicide. Beethoven writes, “my ears keep buzzing and humming day and night, and if someone yells, it is unbearable to me.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No.1 in C major, Op. 21

The young Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven continued to perform publically, and he was very careful to not reveal his deafness. He rightly believed that it would ruin his career. He writes, “I don’t hear the high notes of the instruments and voices, and sometimes, I cannot hear people who speak quietly. I can hear the sounds, but not the words. I can with truth say that my life is very wretched. For nearly 2 years past I have avoided all society, because I find it impossible to say to people, ‘I am deaf!’ In any other profession this might be more tolerable, but in mine such a condition is truly frightful. As for my enemies, of whom I have a fair number, what would they say?” In June 1801 Beethoven confides in his Bonn friend F. G. Wegeler, “that the malicious demon, however, bad health, has been a stumbling-block in my path; my hearing during the last three years has become gradually worse.” At that particular time, Ludwig van Beethoven was still hoping that his doctors might be able to help him. He was aware that his hearing loss would present some problems in his professional life, and “what was of equal importance for him, his social life as well.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 14, No. 4

Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven, Beethoven’s brother

In a letter to his good friend Karl Amenda, Beethoven writes, “Your Beethoven is leading a very unhappy life and is at variance with Nature and his Creator…When I am playing and composing my affliction is hampering me least—it is affecting me most when I am in company.” However, he also reports that Lichnowsky had agreed to pay him an annuity of 600 florins for some years, removing all his financial concerns. His childhood friend Stephan von Breuning had moved to Vienna, and six or seven publishers were competing for each new work. “I often produce three or four works at the same time,” he writes. “My piano playing has considerably improved, and at the moment I feel equal to anything.” Predictably, Beethoven consulted a number of doctors in the hope of finding a cure for his hearing troubles. Initially he looked up Johann Frank, a local professor of medicine. Frank believed that the cause of Beethoven’s hearing loss was related to his abdominal problems. He prescribed a number of traditional herbal remedies that included pushing balls of cotton soaked in almond oil into his ears. Beethoven reports, “Frank has tried to tone up my constitution with strengthening medicines, and my hearing with almond oil, but much good did it do me! His treatment had no effect, my deafness became even worse, and my abdomen continued to be in the same state as before.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Serenade in D major Op. 25

Beethoven’s ear trumpets

Gerhard von Vering was a former German military surgeon and subsequently the Director of the Viennese Health Institute. He was a celebrity doctor, and among his patients was none other than Emperor Joseph II. When Frank’s almond oil treatment showed no healing effect, Beethoven consulted von Vering. He recommended that Beethoven take daily “Danube baths.” Beethoven followed that advice, and sat in tepid baths of river water combined with the ingestion of a small vial of herbal tonic. Apparently, “this treatment miraculously improved Beethoven’s digestive ailments, but his deafness not only persisted, it became even worse.” Beethoven continued to see Dr. von Vering for several months, but he started to protest the increasingly bizarre and unpleasant treatments. It was reported that Dr. Vering strapped toxic bark to Beethoven’s forearms that caused his skin to blister and itch painfully for several days at the time. Beethoven reports to his friend Franz Wegeler in November 1801, “Vering, for the last few months, has applied blisters to both my arms, consisting of a certain bark … This is a most disagreeable remedy, as it deprives me of the free use of my arms for two or three days at a time, until the bark has drawn sufficiently, which occasions a good deal of pain. It is true the ringing in my ears is somewhat less than it was, especially in my left ear where the illness began, but my hearing is by no means improved; indeed I am not sure but that the evil is increased … I am upon the whole much dissatisfied with Vering; he cares too little about his patients.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15

Beethoven, 1801

Dr. Johann Adam Schmidt had also started his medical career as an army surgeon. In 1789 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy in Vienna, and he published a number of important scientific articles. Beethoven implicitly trusted Dr. Schmidt, who recommended leeches and bloodletting as a means of treating the composer’s hearing loss. Dr. Schmidt dejectedly wrote to Beethoven after a number of treatments, “From leeches we can expect no further relief.” Schmidt also recommended for Beethoven to have one of his teeth pulled in hopes of improving the gout-related headache from which Beethoven had been suffering. I am not sure Beethoven heeded this particular advice, but he was clearly interested “in the newest trend sweeping medical science at the time, called galvanism.” That particular treatment involved passing a mild electric current through the afflicted part of the body “as a means of simulating normal bodily activity and aiding the healing process.” Beethoven wrote to a friend, “People talk about miraculous cures by galvanism; what is your opinion? A medical man told me that in Berlin he saw a deaf and dumb child recover its hearing, and a man who had also been deaf for seven years recover his—I have just heard that Schmidt is making experiments with galvanism.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in E-flat major, Op. 38

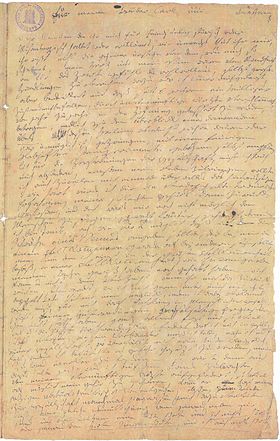

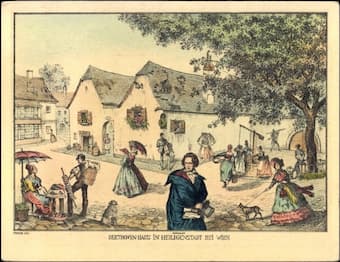

Beethoven’s house in Heiligenstadt

There has been some scholarly debate whether or not Beethoven ever received galvanic treatment. The only known instance comes from an entry in his conversation books from April 1823. Apparently, he conversed with a man suffering from worsening deafness. Beethoven advised, “do not start using hearing aids too soon… Lately, I have not been able to stand galvanism. It is sad. Doctors do not know much, one tires of them eventually.” None of the proposed cures offered any kind of relief, and Beethoven fell into a deep depression. He gradually had begun to realize that his deafness was progressive and probably incurable. Dr. Schmidt finally advised Beethoven to move away from the bustling city and take refuge in the countryside. As such, Beethoven moved to the small town of Heiligenstadt in 1802, at that time located just outside the city limits. Being socially isolated with his hearing further deteriorating, Beethoven wrote a long letter to his two brothers, Carl and Johann, in which he explained his feelings and his condition in great detail, and admitted to having contemplated suicide. He writes, “For six years I have been a hopeless case, aggravated by senseless physicians, cheated year after year in the hope of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31 No. 2 “Tempest”

“The Heiligenstadt Testament”

The “Heiligenstadt Testament”, as this letter has become known, continues, “What a humiliation, when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing, and again I heard nothing. Such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life. Only art it was that withheld me … and so I endured this wretched existence—truly wretched … It was virtue that upheld me in misery, to it, next to my art, I owe the fact that I did not end my life with suicide. Farewell and love each other. I thank all my friends … how glad will I be if I can still be helpful to you in my grave—with joy I hasten towards death. If it comes before I shall have had an opportunity to show all my artistic capacities, it will still come too early for me, despite my hard fate, and I shall probably wish it had come later—but even then I am satisfied, will it not free me from my state? Come when thou will, I shall meet thee bravely. Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 7 in C minor, Op. 30 No. 2

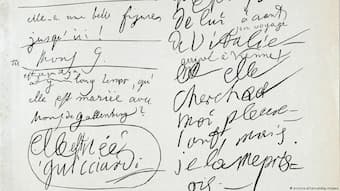

Postcard of Beethoven in Heiligenstadt

Beethoven never posted that letter, and it was only discovered in his papers after his death. In this famous letter, Beethoven addressed and possibly resolved his inner turmoil. He came to terms with the fact that his hearing would never improve, and it marked a turning point in his life. Beethoven was ready to “seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely—it would be so lovely to live a thousand lives.” This newly found zest for life was also “brought about by a dear charming girl who loves me and whom I love,” as Beethoven confided in a friend. “For the first time I feel that marriage might bring me happiness. Unfortunately she is not of my class.” This “dear charming girl” was no doubt the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi who had not yet celebrated her 17th birthday. Although she was flattered to receive attention from the famous Beethoven, Giulietta wasn’t inclined to take Beethoven’s devotion very seriously. Beethoven noted on one of his musical sketches, “Let your deafness no longer be a secret—even in art.” Determined to continue living for and through his art, he promised “a completely new way of composing.” This new way is reflected in a series of compositions that reflect or embody extra-musical ideas of heroism.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

Waldmüller: Beethoven (1823)

While Beethoven was able to compose music, playing concerts, which had been an important source of income, became increasingly difficult. His student Carl Czerny once said that Beethoven could still hear speech and music normally until about 1812. By 1818, however, “Beethoven’s deafness had progressed to such an extent that, with increasing frequency, he began to carry blank books with him, so that his friends and acquaintances, especially when in public, could write their sides of conversations without being overheard, while Beethoven himself customarily replied orally.” Scholars have suggested that Beethoven never became completely deaf, and that he was able to hear muffled words when they were spoken directly into his left ear. Even in his final years, Beethoven was apparently still able to distinguish low tones and sudden loud sound.

Beethoven’s conversation notebook

One day after his death on 27 March, the Institute of Pathology in Vienna performed an autopsy with “specific focus on his ears and the cochlear nerves…” The Eustachian tube was very thickened… and the facial nerves of considerable thickness; the auditory nerves on the other hand shrunken and without pith; the accompanying auditory arteries were of a calibre of a crow-quill, and of cartilaginous consistency. The left auditory nerve, much thinner, arose by three very thin, greyish roots; the right by one root, stronger and pale white… The vault of the skull showed great tightness throughout and a thickness of about half an inch”. Today, physicians are generally in agreement that Beethoven’s deafness was caused by otosclerosis, a condition that exhibits abnormal bone growth inside the ear. In Beethoven’s case, this was accompanied by the degeneration of the auditory nerve. For almost 25 years of his life Ludwig van Beethoven struggled with his severe disability, but his passion for art was all consuming. Music became a mode of self-expression that “transcended the mundane and the narcissistic, as he artistically realized the potential for optimism and idealism within all of us.” Beethoven’s music is an endearing monument to the persistence of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)