It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Julie Huard - Die With A Smile (Live Version)

Nicole Scherzinger Disney Mulan "Reflection" Live Coronation Concert

Colors of the Wind - Live Orchestra | Pocahontas Masterpiece

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

13 year old performs Bohemian Rhapsody in front of 10,000+ students!

Michel Béroff at 75: a pianist beyond borders

James Jolly

With a milestone birthday on the horizon, James Jolly meets the pianist Michel Béroff to find out how this French musician forged a major reputation with a broad repertoire

Often when I’ve interviewed French pianists the subject has been their native music, and, invariably, after enthusing about their extraordinary rich musical heritage – Debussy, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Satie, Fauré, Messiaen and many others – they’d pause and say something along the lines of: ‘But I wish concert promoters/A&R executives would ask me to play some Brahms or Beethoven’. It’s not something an Italian, British or American pianist would ever have to worry about, but for some reason French players have invariably been constrained – hardly le mot juste – to play their own music. It’s no hardship, of course, and it has given us some staggering performances and recordings. (Nowadays things have relaxed a bit – Alexandre Kantorow, for example, is one of the finest Brahms players of his generation and he sailed through the three rounds of the 2019 Tchaikovsky Competition offering just a single Fauré nocturne to fly the Tricolour.) One pianist, though, who side-stepped this pigeon-holing very early on – though he certainly hasn’t avoided French music – is Michel Béroff, who celebrates his 75th birthday on May 9. To mark the occasion Erato has gathered together all his recordings made for the label and the various branches of EMI and issued them in a 42-CD set. And nestling among them is his set of the five Prokofiev piano concertos that put him on the international music map (not to mention his cherishable Debussy recordings including Pour le piano, Estampes, Images, Préludes and much else.)

I took the train to Paris to talk to Béroff, a musician who introduced me to a large swathe of the piano repertoire in my teens, to look back over a distinguished career. We met up on a beautiful spring day and reminisced over a cup of coffee.

20th-century music was natural to me because when you are young, your mind is open, your hard drive empty

MICHEL BÉROFFThere are a number of his recordings I’ve owned for years that I wanted to ask him about, and the first was – yes, French music! – Olivier Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, a work he recorded at the Abbey Road studios in 1968 while still a teenager. ‘I first met Messiaen when I was 11 years old, so it would have been in 1961. It came about because my father took a few lessons with Messiaen during the war and we also had a friend who was one of his harmony students. So I started playing his music because my father loved it very much – my mother had bought him the score of Vingt regards sur l’enfant Jésus. Since I was learning the piano he gave me the music and I began to play some of the pieces – I was maybe nine years old. Then, at 11, I went to a meeting with Messiaen, and I played for him and [his wife, the pianist] Yvonne Loriod.’ I suggest that they must have pretty amazed at this little boy playing such music. Béroff laughs. ‘Of course! They’d never seen anyone so young playing these pieces. So that was how I began with his music. And then I won First Prize in the Messiaen Competition in 1967. I was only the second person after Loriod to play the complete Vingt regards. Of course being young there were so many things I should have asked Messiaen but at that age you don’t think like that. I used to see him a lot and knowing a composer is fantastic, and I should have been more curious. But Messiaen’s music has been like baby milk to me – I heard it even before I started playing. And for me it was always very natural. It’s been with me throughout my life.’

Michel Béroff recording in Leipzig with the Gewandhaus Orchestra and Kurt Masur

The HMV recording of the Quartet, the work that Messiaen wrote for clarinet, violin, cello and piano in 1940 while a prisoner of war in Stalag VIII-A, followed Béroff’s win in the Messiaen prize. For it the 18-year-old Béroff was partnered by some pretty illustrious UK-based players, all of whom were at least 25 years older than him: Gervase de Peyer (clarinet), Erich Gruenberg (violin) and William Pleeth (cello). ‘They were really wonderful musicians,’ Béroff recalls. ‘Before the sessions I went to see Messiaen for advice. He didn’t actually have much to say: it was just a question of adjusting some dynamics, and where the music was so slow that even a string or woodwind player could not do it without too much phrasing, he agreed that it should be a little bit faster than what he wrote. So it was just a few small things which I still have in my score. I was really very happy to do this because it was a great introduction to making recordings. The sleeve design was done by a woman called Arlette de Grouchy – she was in charge of the recording covers – and she had found this image which I found very flashy. But Messiaen, who experienced synaesthesia, approved because he couldn’t see any colours that he didn’t like!’

Béroff enlarged on his approach to the repertoire. ‘This 20th-century music was something natural to me, because when you are young, you are free, your mind is open. You have lots of places inside you – your hard drive is really empty. So it could be Webern or Boulez or Schoenberg – everything is simple to learn. There is no contradiction. You can learn sometime Bach or Mozart or Schoenberg. If you do this later, intellectually it’s much more difficult. So for me it was natural, but it was also out of the question not to play Mozart, Liszt, Chopin, Schumann, Beethoven – all the things which you learn and just couldn’t live without. Someone told me about some kind of biography of me they’d read – it was so ridiculous – it said I was playing only 20th-century music, except the Mozart sonatas! This was stupid because I played some Mozart but never made Mozart a big part of my repertoire. But of course Russian repertoire has been very important – I’ve played a lot of Stravinsky, Mussorgsky and, of course, Prokofiev. Maybe it was my background – my father was born in Bulgaria which is very close to Russia. But Bartók I love even more than Prokofiev, I must say. For me he is the greatest of the composers of the first part of the 20th century.’

Two other recordings I wanted to talk to Michel Béroff about were ones he made in 1974 in Leipzig with the Gewandhaus Orchestra and Kurt Masur – that career-changing set of the complete Prokofiev piano concertos and all of Liszt’s concertante works for piano. ‘I’m not sure why they were made in Leipzig,’ Béroff muses. ‘Probably it had to do with being cheaper. If they didn’t sell well it wouldn’t be too bad! It was always very strange having to go to Berlin and pass through Checkpoint Charlie. But the orchestra was very fine – the only thing that sometimes was a weakness with those East German ensembles were the woodwinds because they didn’t have access to good instruments. Kurt Masur in Leipzig was very strict, and worked everyone very hard. Interestingly, when he later came to the West – I worked with him in London, in New York and on tour – he became much more free, much nicer and much more generous. He was a different person, a very nice man.’ (Béroff also played with the Staatskapelle Dresden and Eugen Jochum. He recalls that it was his first Brahms Second Concerto and it was broadcast. He was asked for his permission, more as a courtesy, and was then rather surprised when in Japan some time later he saw that the performance had been issued on LP.)

The Prokofiev set was only the second of the five concertos to be made in the West (preceded by John Browning’s RCA survey with the Boston Symphony and Erich Leinsdorf, and subsequently reissued by Testament). To return to my opening comments about French repertoire and French pianists, Béroff attributes his atypical repertoire to his teacher, one of the major musical figures in France at the time, to Pierre Sancan, who also taught, inter alia, Jean-Philippe Collard, Emile Naoumoff, Jacques Rouvier, Jean-Bernard Pommier and Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (who credited Sancan as being ‘the Master who gave me all the means I needed … to truly become a pianist’).

Sancan’s method, and he is known for tailoring his approach to his individual students, drew on the Russian school of pianism. As Béroff explains it, it was not only focused on the fingers and sometimes the wrists à la française, but also involved the arms and shoulders – the resultant, and more muscular, approach clearly set Béroff up to tackle the Prokofiev concertos (something that Bavouzet would later also do, with comparable success). The Prokofiev set was a commercial hit, and Béroff would later often play all the concertos, Nos 3 and 5 the most, and when he had to take a break from performance with two hands due to focal dystonia, he would play No 4 (for the left hand) quite often. But when pressed he revealed a particular fondness for No 2 – ‘You know, like with Bartók, No 2 is my favourite. And this number is magic for composers … just think of Brahms No 2!’

The Prokofiev set led to the Liszt collection. ‘Obviously there were quite a few pieces which I’d never played – and never have since! – and I suspect there have been a few other things that have been found since then. But at the time it was the first complete recording of all the music for piano and orchestra. And there are some wonderful things there, like that early piece for strings, Malédiction, with some very avant-garde writing. It was very interesting for me to do this and I enjoyed it very much and obviously I got along very well with Masur.’

Mention of Kurt Masur led us on to some of Béroff’s other conductor collaborators: ‘I was really fascinated by Seiji Ozawa [with whom he recorded the Stravinsky concertante works]. Pierre Boulez – there’s was really nothing to say because he was so helpful. We started with Bartók’s Second with the New York Philharmonic in 1972. We often worked together and he was so nice. He had quite a reputation but it couldn’t have been more wrong. Of course, if someone was trying to trap him with questions, he could kill them in just one sentence. An Englishman I liked very much was Colin Davis. He was a very good musician, so humble and such a nice person to work with, really fantastic. I also enjoyed working with Andrew Davis, a very warm person. Bernstein, of course, because he was such an amazing man! And Michael Tilson Thomas was also great to work with, probably because he was also a really good pianist. And André Previn [with whom Béroff made one of the finest recordings ever of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie] was such a gifted musician. And Claudio Abbado [with whom he recorded, for DG, the Ravel Left-hand Concerto] was such a wonderful conductor.’

These days Béroff conducts, teaches – Seong-Jin Cho was one of his students – and sits on numerous competition juries. The Chopin Competition beckons later this year, but meanwhile he’s still surprised, and flattered, to be the focus of this retrospective Erato set, quite a tribute to a musician who has contributed so much to the recorded catalogue.

Sunday, April 27, 2025

3 Songs That Make Us Cry Every Time | Les Misérables

Friday, April 25, 2025

KATICA ILLÉNYI - Once Upon a Time in the West

Ludwig von Beethoven “The Sounds of Silence”

by Georg Predota

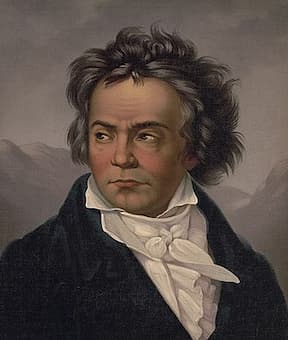

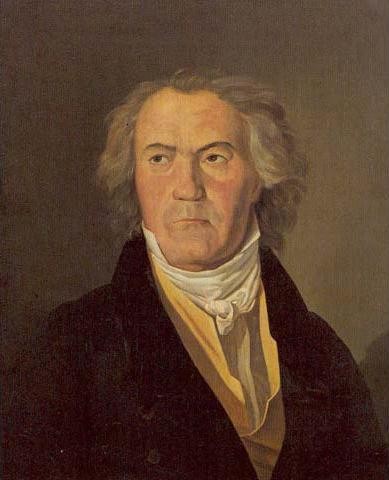

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1818

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was the rising star on the Viennese music scene in the last decade of the 18th century. He made his name by showcasing his talents as a pianist, and he composed and performed piano sonatas of extreme technical difficulty. At the same time he composed music for a variety of musical ensemble and occasions. Ludwig van Beethoven needed to be busy, because he was a freelance musician. In fact, he was the first major composer in that city who did not depend on a fixed musical appointment. However, Beethoven had a dark secret. During his mid-20s, he gradually started to lose his hearing. At first, these periods of temporary hearing loss might not have caused him much concern, as he had suffered from a number of ailments, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and spells of fever since childhood. It seems that he noticed the first symptoms in 1796, or possibly somewhat earlier. In 1815, he told the English pianist Charles Neate that the cause of his hearing loss could be traced back to a quarrel he had with a singer in 1798.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2, No. 3

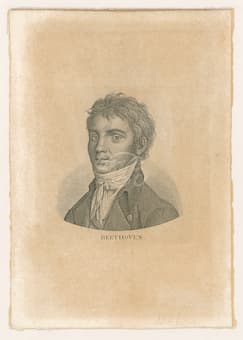

Beethoven, 1800-01

The story goes that a tenor was visiting Beethoven in his apartment. Apparently, they got into a heated argument and the tenor stormed out in a huff. Unexpectedly he returned and knocked on the door. Beethoven is said to have jumped up from the piano angrily to rush and open the door. However, his leg got stuck and he fell face down to the floor. This small accident was not the cause of Beethoven’s deafness, but it triggered a long and continuous hearing loss that would end in almost complete silence. Supposedly, Beethoven said about that particular fall, “I found myself deaf, and have been so ever since.” The hearing loss initially affected mostly his left ear, and as it grew worse Beethoven started to suffer from a severe form of tinnitus. The continued buzzing in his ear made it increasingly difficult to hear music or conversations, and it drove him to the brink of suicide. Beethoven writes, “my ears keep buzzing and humming day and night, and if someone yells, it is unbearable to me.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No.1 in C major, Op. 21

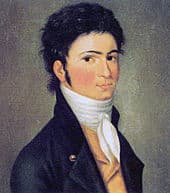

The young Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven continued to perform publically, and he was very careful to not reveal his deafness. He rightly believed that it would ruin his career. He writes, “I don’t hear the high notes of the instruments and voices, and sometimes, I cannot hear people who speak quietly. I can hear the sounds, but not the words. I can with truth say that my life is very wretched. For nearly 2 years past I have avoided all society, because I find it impossible to say to people, ‘I am deaf!’ In any other profession this might be more tolerable, but in mine such a condition is truly frightful. As for my enemies, of whom I have a fair number, what would they say?” In June 1801 Beethoven confides in his Bonn friend F. G. Wegeler, “that the malicious demon, however, bad health, has been a stumbling-block in my path; my hearing during the last three years has become gradually worse.” At that particular time, Ludwig van Beethoven was still hoping that his doctors might be able to help him. He was aware that his hearing loss would present some problems in his professional life, and “what was of equal importance for him, his social life as well.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 14, No. 4

Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven, Beethoven’s brother

In a letter to his good friend Karl Amenda, Beethoven writes, “Your Beethoven is leading a very unhappy life and is at variance with Nature and his Creator…When I am playing and composing my affliction is hampering me least—it is affecting me most when I am in company.” However, he also reports that Lichnowsky had agreed to pay him an annuity of 600 florins for some years, removing all his financial concerns. His childhood friend Stephan von Breuning had moved to Vienna, and six or seven publishers were competing for each new work. “I often produce three or four works at the same time,” he writes. “My piano playing has considerably improved, and at the moment I feel equal to anything.” Predictably, Beethoven consulted a number of doctors in the hope of finding a cure for his hearing troubles. Initially he looked up Johann Frank, a local professor of medicine. Frank believed that the cause of Beethoven’s hearing loss was related to his abdominal problems. He prescribed a number of traditional herbal remedies that included pushing balls of cotton soaked in almond oil into his ears. Beethoven reports, “Frank has tried to tone up my constitution with strengthening medicines, and my hearing with almond oil, but much good did it do me! His treatment had no effect, my deafness became even worse, and my abdomen continued to be in the same state as before.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Serenade in D major Op. 25

Beethoven’s ear trumpets

Gerhard von Vering was a former German military surgeon and subsequently the Director of the Viennese Health Institute. He was a celebrity doctor, and among his patients was none other than Emperor Joseph II. When Frank’s almond oil treatment showed no healing effect, Beethoven consulted von Vering. He recommended that Beethoven take daily “Danube baths.” Beethoven followed that advice, and sat in tepid baths of river water combined with the ingestion of a small vial of herbal tonic. Apparently, “this treatment miraculously improved Beethoven’s digestive ailments, but his deafness not only persisted, it became even worse.” Beethoven continued to see Dr. von Vering for several months, but he started to protest the increasingly bizarre and unpleasant treatments. It was reported that Dr. Vering strapped toxic bark to Beethoven’s forearms that caused his skin to blister and itch painfully for several days at the time. Beethoven reports to his friend Franz Wegeler in November 1801, “Vering, for the last few months, has applied blisters to both my arms, consisting of a certain bark … This is a most disagreeable remedy, as it deprives me of the free use of my arms for two or three days at a time, until the bark has drawn sufficiently, which occasions a good deal of pain. It is true the ringing in my ears is somewhat less than it was, especially in my left ear where the illness began, but my hearing is by no means improved; indeed I am not sure but that the evil is increased … I am upon the whole much dissatisfied with Vering; he cares too little about his patients.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15

Beethoven, 1801

Dr. Johann Adam Schmidt had also started his medical career as an army surgeon. In 1789 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy in Vienna, and he published a number of important scientific articles. Beethoven implicitly trusted Dr. Schmidt, who recommended leeches and bloodletting as a means of treating the composer’s hearing loss. Dr. Schmidt dejectedly wrote to Beethoven after a number of treatments, “From leeches we can expect no further relief.” Schmidt also recommended for Beethoven to have one of his teeth pulled in hopes of improving the gout-related headache from which Beethoven had been suffering. I am not sure Beethoven heeded this particular advice, but he was clearly interested “in the newest trend sweeping medical science at the time, called galvanism.” That particular treatment involved passing a mild electric current through the afflicted part of the body “as a means of simulating normal bodily activity and aiding the healing process.” Beethoven wrote to a friend, “People talk about miraculous cures by galvanism; what is your opinion? A medical man told me that in Berlin he saw a deaf and dumb child recover its hearing, and a man who had also been deaf for seven years recover his—I have just heard that Schmidt is making experiments with galvanism.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in E-flat major, Op. 38

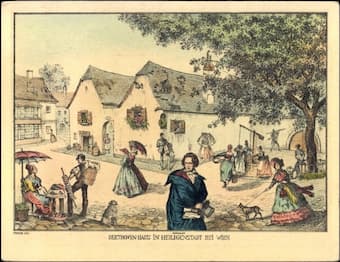

Beethoven’s house in Heiligenstadt

There has been some scholarly debate whether or not Beethoven ever received galvanic treatment. The only known instance comes from an entry in his conversation books from April 1823. Apparently, he conversed with a man suffering from worsening deafness. Beethoven advised, “do not start using hearing aids too soon… Lately, I have not been able to stand galvanism. It is sad. Doctors do not know much, one tires of them eventually.” None of the proposed cures offered any kind of relief, and Beethoven fell into a deep depression. He gradually had begun to realize that his deafness was progressive and probably incurable. Dr. Schmidt finally advised Beethoven to move away from the bustling city and take refuge in the countryside. As such, Beethoven moved to the small town of Heiligenstadt in 1802, at that time located just outside the city limits. Being socially isolated with his hearing further deteriorating, Beethoven wrote a long letter to his two brothers, Carl and Johann, in which he explained his feelings and his condition in great detail, and admitted to having contemplated suicide. He writes, “For six years I have been a hopeless case, aggravated by senseless physicians, cheated year after year in the hope of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31 No. 2 “Tempest”

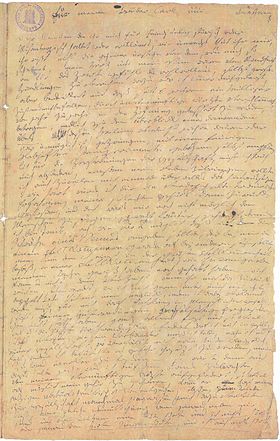

“The Heiligenstadt Testament”

The “Heiligenstadt Testament”, as this letter has become known, continues, “What a humiliation, when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing, and again I heard nothing. Such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life. Only art it was that withheld me … and so I endured this wretched existence—truly wretched … It was virtue that upheld me in misery, to it, next to my art, I owe the fact that I did not end my life with suicide. Farewell and love each other. I thank all my friends … how glad will I be if I can still be helpful to you in my grave—with joy I hasten towards death. If it comes before I shall have had an opportunity to show all my artistic capacities, it will still come too early for me, despite my hard fate, and I shall probably wish it had come later—but even then I am satisfied, will it not free me from my state? Come when thou will, I shall meet thee bravely. Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 7 in C minor, Op. 30 No. 2

Postcard of Beethoven in Heiligenstadt

Beethoven never posted that letter, and it was only discovered in his papers after his death. In this famous letter, Beethoven addressed and possibly resolved his inner turmoil. He came to terms with the fact that his hearing would never improve, and it marked a turning point in his life. Beethoven was ready to “seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely—it would be so lovely to live a thousand lives.” This newly found zest for life was also “brought about by a dear charming girl who loves me and whom I love,” as Beethoven confided in a friend. “For the first time I feel that marriage might bring me happiness. Unfortunately she is not of my class.” This “dear charming girl” was no doubt the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi who had not yet celebrated her 17th birthday. Although she was flattered to receive attention from the famous Beethoven, Giulietta wasn’t inclined to take Beethoven’s devotion very seriously. Beethoven noted on one of his musical sketches, “Let your deafness no longer be a secret—even in art.” Determined to continue living for and through his art, he promised “a completely new way of composing.” This new way is reflected in a series of compositions that reflect or embody extra-musical ideas of heroism.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

Waldmüller: Beethoven (1823)

While Beethoven was able to compose music, playing concerts, which had been an important source of income, became increasingly difficult. His student Carl Czerny once said that Beethoven could still hear speech and music normally until about 1812. By 1818, however, “Beethoven’s deafness had progressed to such an extent that, with increasing frequency, he began to carry blank books with him, so that his friends and acquaintances, especially when in public, could write their sides of conversations without being overheard, while Beethoven himself customarily replied orally.” Scholars have suggested that Beethoven never became completely deaf, and that he was able to hear muffled words when they were spoken directly into his left ear. Even in his final years, Beethoven was apparently still able to distinguish low tones and sudden loud sound.

Beethoven’s conversation notebook

One day after his death on 27 March, the Institute of Pathology in Vienna performed an autopsy with “specific focus on his ears and the cochlear nerves…” The Eustachian tube was very thickened… and the facial nerves of considerable thickness; the auditory nerves on the other hand shrunken and without pith; the accompanying auditory arteries were of a calibre of a crow-quill, and of cartilaginous consistency. The left auditory nerve, much thinner, arose by three very thin, greyish roots; the right by one root, stronger and pale white… The vault of the skull showed great tightness throughout and a thickness of about half an inch”. Today, physicians are generally in agreement that Beethoven’s deafness was caused by otosclerosis, a condition that exhibits abnormal bone growth inside the ear. In Beethoven’s case, this was accompanied by the degeneration of the auditory nerve. For almost 25 years of his life Ludwig van Beethoven struggled with his severe disability, but his passion for art was all consuming. Music became a mode of self-expression that “transcended the mundane and the narcissistic, as he artistically realized the potential for optimism and idealism within all of us.” Beethoven’s music is an endearing monument to the persistence of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

The Bach Family: Eight Fascinating Relatives of Johann Sebastian

by Emily E. Hogstad

Many music history lovers know that Johann Sebastian Bach had many children: twenty kids by two wives.

What fewer people know is that the wider Bach family was famously fertile…as well as famously musical.

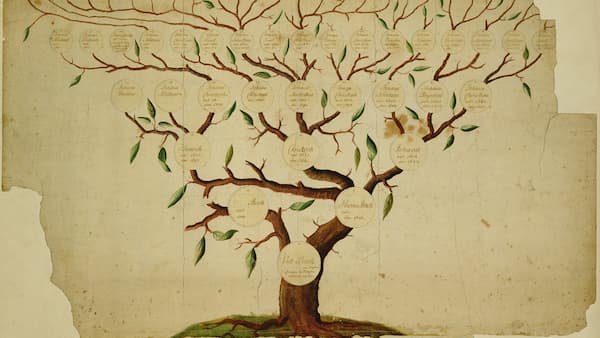

The Bach family tree © aco.com.au

In fact, the Wikipedia article on the Bach family includes over 75 names.

Many of these Bachs – who lived before, during, and after the lifespan of Johann Sebastian Bach – were professional musicians.

Today we’re taking a look at ten of the most interesting musical Bachs who weren’t Johann Sebastian or his children.

(If you want to find out what happened to Bach’s twenty children, we wrote an article about them here.)

Let’s get started!

Veit Bach (1550-1619)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s great-great-grandfather

The Veit-Bach-Mill at Thuringia

Veit Bach was born around 1550 near present-day Bratislava in the Kingdom of Hungary. He worked as a miller and a baker.

During his lifetime, the Kingdom of Hungary was under the control of the Vienna-based Hapsburg dynasty. The Hapsburgs were Catholic, while Veit was Protestant.

At the time, Protestantism was a relatively new movement. Martin Luther had released his famous Ninety-five Theses, a protest against what he viewed as Catholic corruption, in 1517, only a generation before Veit Bach was born.

To escape religious persecution, Veit Bach moved to Wechmar in the German state of Thuringia, almost halfway between the cities of Leipzig and Frankfurt.

He continued working as a miller after the move. According to local legend, he would play an instrument called the cythringen, a kind of Renaissance-era guitar-like instrument, in rhythm to the sounds of the mill.

Johannes Bach I (15?? – 1626)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s great-grandfather

Johannes Bach I was Veit Bach’s son and born in Wechmar. We’re not sure what year.

According to a family genealogy that Johann Sebastian Bach and his sons assembled generations later, Johannes began his professional life as a baker.

Later, however, he took an apprenticeship as a town piper in the town of Gotha, ten kilometers away from his birthplace.

Tragically, he died of the plague in 1626.

Interestingly, the eulogy for one of Johannes Bach I’s sons stated that his father had once been a carpet weaver. The early members of this musical dynasty clearly had non-musical day jobs to support themselves.

Christoph Bach (1613-1661)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s grandfather

Johannes Bach I had several musician sons. One of them was Christoph Bach, who was born in Wechmar, becoming a court musician there. His brothers also became musicians.

During his career, Christoph Bach took musical jobs in the neighboring towns of Erfurt and Arnstadt. (His famous grandson Johann Sebastian would work in Arnstadt, too.)

He married a woman named Maria Magdalena Grabler. She had three sons: Georg Christian Bach in 1642 and twins Johann Ambrosius Bach and Johann Christian Bach in 1645. (Twins ran in the Bach family!)

Christoph Bach died in 1661 in Arnstadt.

Johann Ambrosius Bach (1645-1695)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s father

Johann Ambrosius Bach, J.S. Bach’s father

Johann Ambrosius Bach and his twin Johann Christoph were born in 1645, when their father was working as a musician in Erfurt.

Johann Ambrosius would have been surrounded by music at an early age. He ultimately followed in his father’s footsteps and became a professional violinist and trumpet player.

Tragically, Johann Ambrosius became an orphan when he was just 16. He and his twin moved in with an uncle until they could support themselves.

In 1668, when Johann Ambrosius was 23, he married a woman named Maria Elisabeth Lämmerhirt.

In 1671, the couple moved to Eisenach, forty kilometers from Wechmar, so that Johann Ambrosius could take a job as the town musician. Together they would have eight children, including Johann Sebastian in 1685.

Tragedy struck in the spring of 1694 when Maria Elisabeth died.

Johann Ambrosius, in desperate need of a wife to help raise his children, remarried that November.

But this union was doomed, too: he died in March 1695, making Johann Sebastian Bach an orphan just weeks before his tenth birthday.

Johann Christoph Bach (1645-1693)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s uncle

Johann Christoph Bach was Johann Ambrosius Bach’s twin.

One of Johann Sebastian Bach’s sons later wrote, “They loved each other tenderly, and looked so much alike that even their own wives could not distinguish them.”

Like his twin and their father, Johann Christoph became a professional musician, first working in the town band in Erfurt and later as a violinist in the Arnstadt court.

Johann Christoph had a volatile temper and lashed out at the musicians in Arnstadt. (Apparently, high tempers and perfectionism ran in the Bach family!) Things got so bad that he was fired.

In 1682, he got his job back, thanks to the intervention of Arnstadt-based Count Anton Günther II, a celebrated patron of music.

Johann Christoph’s biggest claim to fame might be that he introduced his nephew Johann Sebastian to the organ.

Johann Christoph Bach (1671-1721)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s brother

Here’s another Johann Christoph Bach! (The family loved reusing names.)

This particular Johann Christoph Bach was born in Erfurt in 1671, but raised in Eisenach, where his brother Johann Sebastian, fourteen years his junior, was born.

In 1686, as a teenager, he was sent back to Erfurt to apprentice under Johann Pachelbel. He worked as an organist in Erfurt and Arnstadt.

In 1690, he got a job playing organ in the nearby town of Ohrdruf. His and Johann Sebastian’s mother died in the spring of 1694, and their father less than a year later.

In between his parents’ deaths, Johann Christoph got married to a woman named Dorothea von Hof. This meant that after his father’s death, he was no longer a bachelor and was in a position to take in ten-year-old Johann Sebastian.

Not only did Johann Christoph take in Johann Sebastian, he also continued his musical education.

We don’t know exactly what their relationship was like, but Bach’s biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel wrote in his 1802 biography:

The most renowned Clavier composers of that day were Froberger, Fischer, Johann Caspar Kerl, Pachelbel, Buxtehude, Bruhns, and Böhm. Johann Christoph possessed a book containing several pieces by these masters, and [Johann Sebastian] Bach begged earnestly for it, but without effect. Refusal increasing his determination, he laid his plans to get the book without his brother’s knowledge. It was kept on a book-shelf which had a latticed front. Bach’s hands were small. Inserting them, he got hold of the book, rolled it up, and drew it out. As he was not allowed a candle, he could only copy it on moonlight nights, and it was six months before he finished his heavy task. As soon as it was completed, he looked forward to using in secret a treasure won by so much labour. But his brother found the copy and took it from him without pity, nor did Bach recover it until his brother’s death soon after.

If the story is true, Johann Sebastian didn’t hold his brother’s strictness against him. He later composed a Capriccio in E major (BWV 993) in honor of Johann Christoph.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Capriccio in E Major, BWV 993

Johann Ernst Bach I (1683-1739)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s cousin

Twins Johann Ambrosius Bach and Johann Christoph Bach both had children. The former fathered Johann Sebastian, while the latter fathered (among others) Johann Ernst Bach I.

Johann Ernst was born in Arnstadt in 1683. Johann Ernst’s father died ten years later. He moved to Ohrdruf to be near family.

After Johann Sebastian’s parents died and he also moved to Ohrdruf, the two musical cousins began going to school together.

He studied briefly in Frankfurt before securing a job there. A few years later, he moved back to Arnstadt and became Johann Sebastian’s organ-playing substitute.

After Johann Sebastian moved away in 1707, Johann Ernst applied for his vacated position. He won the job…but his salary was less than half of what his cousin’s had been.

He died in 1739 in his mid-fifties.

Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach (1759-1845)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s grandson

Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach

Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach was the grandson of Johann Sebastian Bach, through Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach.

He was born in 1759 and received his initial musical training from two of his uncles, C.P.E. Bach and Johann Christian Bach.

When Johann Christian Bach, Johann Sebastian’s youngest son, died in 1782 in London, Wilhelm was present at his deathbed.

Between 1788 and 1811, he worked as Kapellmeister in Berlin at the court of Prince Frederick William II of Prussia. After he received a pension, he retired.

Wilhelm’s most famous piece is possibly the Dreyblatt, a titillating work for piano six hands. It requires one man sitting in the center of the piano bench, with a woman on either side of him. Over the course of the work, the man has to reach behind and around the women.

Dreyblatt für Klavier zu 6 Händen (William Friedrich Ernst Bach)

In 1843, a monument to Johann Sebastian Bach was erected in Leipzig. Composer Robert Schumann was present, as was Wilhelm. Schumann described Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst as “a very agile old gentleman of 84 years with snow-white hair and expressive features.”

Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach had four children. His eldest daughter Caroline died in 1871. She was the last surviving descendant of Johann Sebastian Bach.

He famously said of himself and his work, “Heredity can tend to run out of musical ideas.”