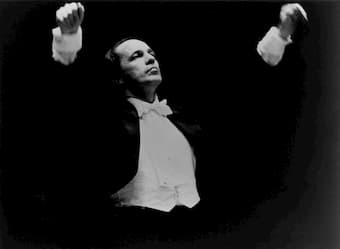

Did you know that Berlioz composed his Symphonie Fantastique in just two months? In 1827, the young composer goes to the theater in Paris for a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The Irish actress Harriet Smithson, performing the role of the tormented Ophelia, entrances him and inspires him to incredible artistic heights, leading him to compose Symphonie fantastique. They did get married eventually in 1833! Watch Leonard Bernstein lead the Orchestre National de France in an exciting interpretation of Berlioz’s unforgettable work, filmed in 1976 at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs Élysées.

It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, January 26, 2025

Love Theme, Orquesta Real de Xalapa, Esencial

Friday, January 24, 2025

9 Unforgettably Beautiful Melodies from SYMPHONIES

A Day in the Life: Daily Creative Habits of the Most Well-Known Classical Composers

by Doug Thomas, Interlude

Beethoven composing at the piano © Bettmann/Corbis

What is the daily life of a composer like? How much time did Mozart spend on composing? Did Bach have a day job? What was Ives’ parallel career? Let’s find out the daily creative habits of some of the most well-known classical composers.

Mozart was known for only spending a couple of hours a day on composing, short sparks of creation; although ideas would constantly flow in his mind. Beethoven, on the opposite, would embark on long uninterrupted lengthy creative processes, lasting until the early morning. Tchaikovsky’s creativity was very fertile, and it took him little time to produce musical material; an hour here and there per day.

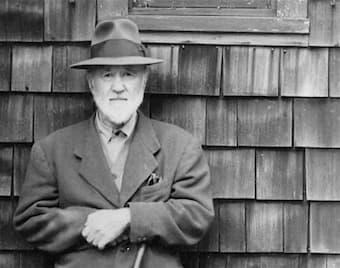

Charles Ives © www.jmeshel.com

Many composers have also been prolific teachers — whether in private circles, such as with Chopin and Liszt, or in religious institutions and conservatoires, such as with Bach and Fauré. Handel, Scarlatti, Haydn, Salieri, Weber and Wagner were all at some point of their career kapellmeister.

Some artists diversified their activities outside of composing, such as Berlioz and Schumann who were also well-known as critics. Other composers ended up being successful performers — especially when it comes to piano music —, such as Schubert and Brahms, and in some cases talented conductors, such as Boulez and Bernstein.

© nspp.mofa.gov.tw

Some composers have sustained their creative activities through a day job, outside of the music world. Ives used to say that “if a composer has a nice wife and some nice children, how can he let them starve on his dissonances?” Verdi was a politician and Glass took on several day jobs — such as plumber and taxi driver — before spending his time solely on composing and performing.

Today, there is a great return from composers to performing their own works. Furthermore, many composers are also recording artists, have their own home studio and release their works independently — in the United Kingdom, examples include Rackham and Crane.

Pierre Boulez © static01.nyt.com

What is there to learn from all this? It is very often a matter of context; Bach’s and Mozart’s music had to be delivered quickly and on a regular basis, therefore it followed particular frames and structures. It was therefore a lot quicker for them to create a piece of music, as they only had to “fill in the blanks”. Beethoven and Wagner on the other hand, wrote independently, freely and spent a lot more time developing new ideas, through trial and error.

Composing is very rarely a single activity, and a good artist often excels at different areas of work that each in some way inform his creativity.

Today’s daily life of a composer has not changed much, although technology has allowed him to share his music quickly, differently and universally. In all, composing and creativity are daily habits.

Life of Chopin: The Controversial Chopin Biography by Liszt

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

On 14 November 1849, Ludwika Jędrzejewicz opened an envelope.

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz

Ludwika Jędrzejewicz was having a bad month. Her marriage was in shambles because she had left Poland to be at her brother Frédéric Chopin’s deathbed.

She had just attended his final illness and funeral and was going through his papers and other personal effects.

She was even preparing to smuggle his heart in a cognac bottle underneath her coat so it could be buried in Poland.

It turns out that the envelope had been sent by no one other than Franz Liszt.

Inside was a questionnaire full of various inquiries about Chopin’s life. Liszt wanted the answers because he was interested in writing a book about Chopin’s life.

On top of the inconsiderate timing, Liszt had included personal questions about her brother’s love life, such as his multi-year liaison with authoress George Sand.

It is believed that the gesture irritated her – or at the least overwhelmed her. She didn’t know what to do with the envelope, so she gave it to Jane Stirling, the wealthy woman who had been serving as Chopin’s concert agent and secretary and who had subsidised Jędrzejewicz’s travels and Chopin’s large funeral.

The fastidious Jane Stirling returned Liszt’s questionnaire to him, but she brushed over some facts in the process. Ultimately, Liszt never used Stirling’s answers.

The First Liszt/Chopin Meetings

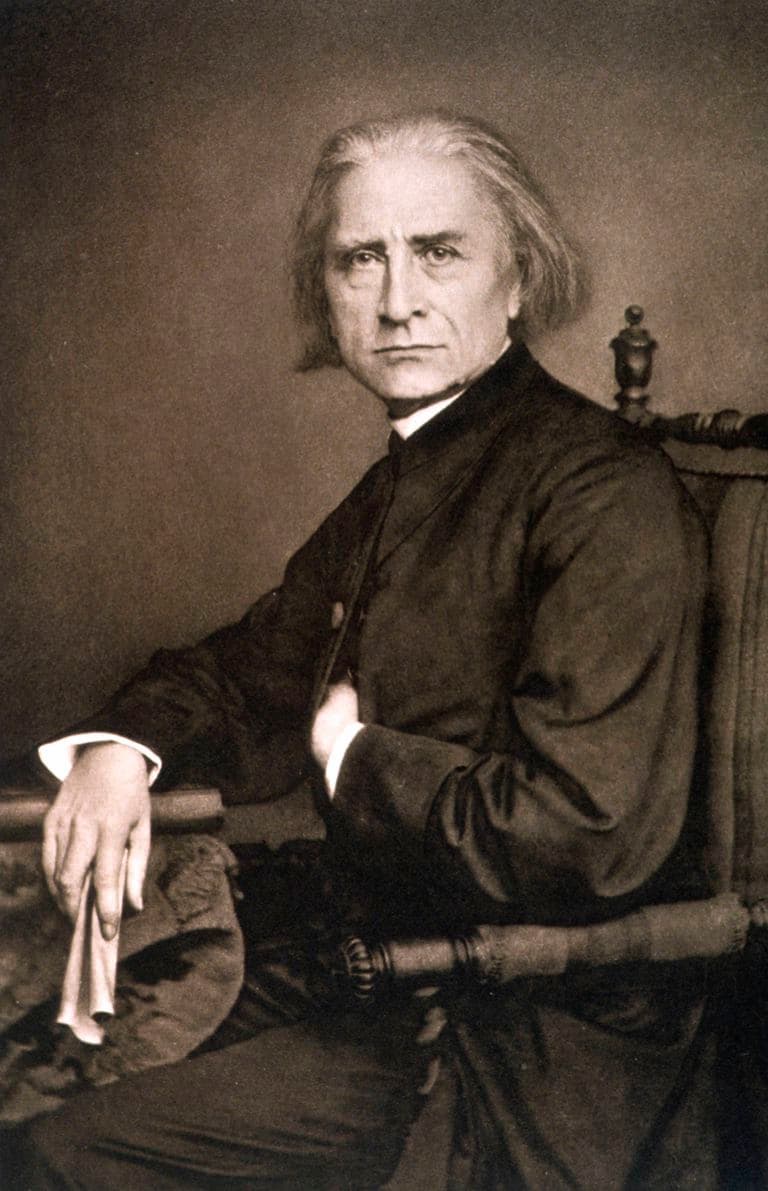

Franz Liszt in 1870

Franz Liszt had known Chopin for many years.

We don’t know when exactly they met, but in December 1831, Chopin wrote a letter to his best friend back in Poland suggesting that he had met Liszt. Liszt would have been twenty and Chopin almost twenty-two at the time.

A few months later, Liszt was in the audience for Chopin’s Parisian debut, which happened at the Salle Pleyel in February 1832.

“We remember his first appearance in the salons of Pleyel, where the most enthusiastic and redoubled applause seemed scarcely sufficient to express our enchantment for the genius which had revealed new phases of poetic feeling and made such happy yet bold innovations in the form of musical art,” Liszt wrote years later in his biography.

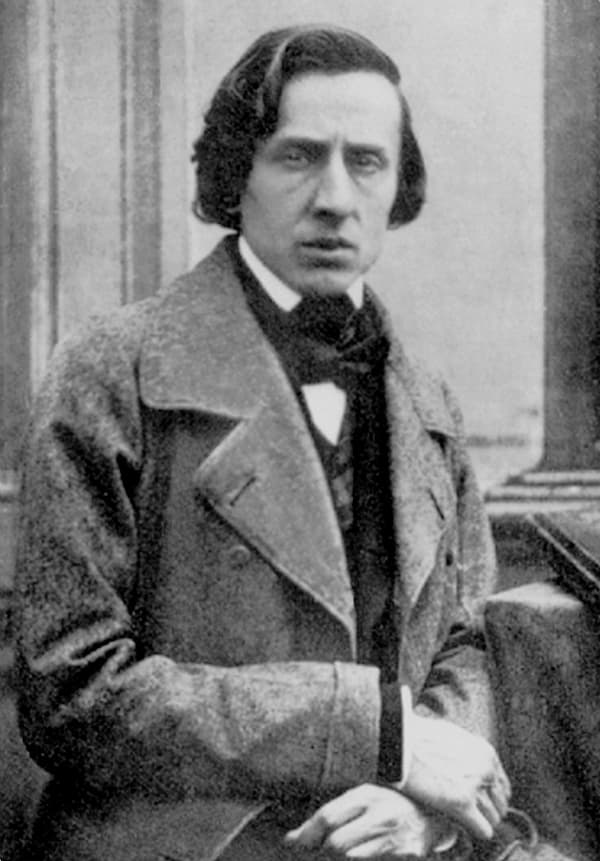

Frédéric Chopin

The two young men became friends and eventually near-neighbours, living a few blocks apart.

They also made a splash performing together in Paris. (Their debut as a duo happened in 1833 at a benefit concert for the bankrupt Harriet Smithson, the actress who Hector Berlioz had written his Symphonie Fantastique and who had since become his fiancée.)

However, they went through their rough patches, too. In 1835, Liszt asked Chopin if he could borrow his apartment while Chopin was away. Chopin agreed. When he returned home, he found out that Liszt had used it for an amorous encounter with the great pianist Camille Marie Pleyel, who had just separated from her husband on account of her infidelities.

On a professional note, there was a certain amount of jealousy, too. Chopin once wrote to a friend, “I should like to rob [Liszt] of the way he plays my studies.” However, he also protested against the way that Liszt added improvisatory elements to a performance of one of his nocturnes. Chopin was so upset that Liszt had to apologise.

Liszt and Chopin’s Romantic Interests

Portrait of Marie d’Agoult by Henri Lehmann, 1843

In 1836, Liszt and his lover, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, hosted a party that would prove fateful to Chopin.

The countess was a great fan of Chopin and extended an invitation to him. She also invited another friend, the radical writer Aurore Dupin, better known by her pen name George Sand, who was arguably the most popular writer in Europe.

Although Chopin was initially put off by the strong-willed Sand, the two eventually fell in love and were a couple for ten years.

Not long after Chopin and Sand paired up, Liszt and the Countess Marie d’Agoult had a protracted and acrimonious breakup.

His next long-term partner was a woman named Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, an unhappily married noblewoman who fell in love with Liszt and remained his partner for forty years. Sayn-Wittgenstein was an extremely prolific author and letter writer, and she encouraged Liszt to also focus on writing, both prose and music.

The Origins of the Chopin Biography

Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

It is believed that after Chopin’s death, Liszt and Sayn-Wittgenstein worked together on the manuscript of the Chopin biography.

The biography began appearing in installments in La France Musicale in 1851.

It turns out that the book was a bit of a disaster. The worshipful Jane Stirling, for one, wasn’t satisfied with how Liszt had described her former boss’s musicianship.

Meanwhile, his Polish friends and family were upset that a non-Pole had published a biography before them, gotten the subtleties of Chopin’s Polish identity wrong, and sucked up all the oxygen in the room when it came to the subject of a Chopin biography. It would be difficult, they believed, for a work by one of them to be taken more seriously than one by Franz Liszt, the internationally renowned musical celebrity…and they were probably right.

George Sand offered her measured thoughts about Liszt’s biography of her ex: “a little exuberant in style but filled with good things and very beautiful pages,” she allowed.

In 1879, Liszt and Sayn-Wittgenstein returned to the project, creating an even longer version, this time, with additional emphasis on Polish politics and identity.

Sayn-Wittgenstein was apparently the driver behind many of the changes, and unfortunately the changes – and her turgid writing style generally – has proven to be unpopular with modern scholars and historians.

The Biography’s Legacy

Life of Chopin by Franz Liszt

Of course, given Liszt’s fame, some of the facts in his biography were distributed in other later biographies.

One of the ideas that gained traction was Chopin’s perceived aristocratic nature.

For instance, it was reported in Liszt’s book that Chopin’s education had been financed by Prince Radziwill (it had not been) and that the friends who he spent the most time with were members of the Polish aristocracy (they were not).

Conclusion

Today, the historians brave enough to wade into the messy, complicated subject of Liszt’s Chopin biography generally believe that while the biography is a helpful document for understanding how Liszt and his Parisian contemporaries viewed Chopin, there’s much about it that’s misleading or even flat-out wrong.

That said, as long as you keep all of that in mind, it’s definitely worth a read, as the English translation has long been in the public domain. So why don’t you download a copy and see what you think?

Intimate and Irresistible Schubert Piano Favourites

By Hermione Lai, Interlude

Franz Schubert

Schubert composed extensively for the piano, with his oeuvre ranging from intimate miniatures to expansive sonatas. Actually, his piano sonatas are central to his piano repertoire. He composed 21 sonatas, combining lyrical, song-like melodies with intricate harmonic progressions. As some commentators have noted, “Schubert bridged the clear formal structures of Classical music with more exploratory and expressive Romantic tendencies.”

Schubert also composed several sets of character pieces, works that reflect his gift for melody and mood. Each work encapsulates a distinct emotional landscape, ranging from deeply introspective to playful. We also find shorter, more whimsical pieces that draw from folk-like rhythms and melodies, giving them a sense of charm and immediacy. To commemorate Schubert’s birthday on 31 January, we decided to dedicate a blog to his 10 most popular piano works.

Impromptu in G-flat Major, Op. 90, No. 3 (D. 899)

Let’s get started with one of Schubert’s most popular and best-loved piano compositions, the Impromptu in G-flat major, Op. 90, No. 3 (D. 899). What a stunning exploration of lyrical elegance and expressive depth. Just listen how Schubert weaves together moments of tranquillity and exuberance!

From the opening notes, the piece introduces a melody that seems to shimmer and flow effortlessly, casting a spell of quiet beauty. The theme is delicate but imbued with a quiet longing, its long and sweeping phrases unfolding as if in a dream. But beneath its serene surface, Schubert crafts subtle harmonic shifts that add layers of complexity and intrigue, creating a sense of ongoing motion.

Schubert’s Impromptu in G-flat Major, Op. 90, No. 3 (D. 899)

The work takes a more playful turn in the middle section. Syncopated rhythms and rapid cascading figures inject a sense of sparkle and vitality. The music suddenly comes alive, even hinting at a joyful dance before returning to the opening’s more introspective and lyrical atmosphere.

Schubert effortlessly navigates between lyrical beauty and impetuous energy, with moments of delicate intimacy and sudden surges of emotion creating an engaging character. As with much of Schubert’s music, there is a sense of improvisation as each phrase feels spontaneous, yet it is carefully crafted. This gorgeous Impromptu is an intimate journey through the full range of human emotions, wrapped in Schubert’s unforgettable signature harmonic richness and melodic inventiveness. For me, it’s a musical miracle!

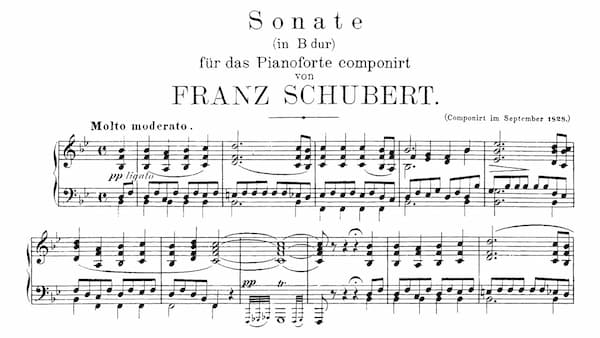

Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960

Franz Schubert composed his B-flat Major Sonata, D. 960, during the final months of his life in 1928. It is a profound and introspective work that showcases the composer’s exceptional ability to express deep emotional complexity through his music. This sonata is often regarded as a summation of his compositional style, blending lyrical beauty, harmonic richness, and a kind of emotional vulnerability. It is a work that speaks with a quiet but unmistakable intensity, reflecting both the joy and the melancholy of Schubert’s final years.

Schubert’s Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960

The sonata is structured in four movements, each offering its own distinct emotional landscape while contributing to the larger narrative of the piece. The grand and restless “Allegro” is filled with tension and lyrical beauty, while the second movement “Andante sostenuto” offers a deeply introspective and meditative contrast. The “Scherzo” injects a playful and complex energy with darker undertones, the concluding “Allegro” reflects Schubert’s creativity and looming mortality.

It’s amazing how Schubert balances a sense of sweeping grandeur with profound intimacy in D. 960. The sonata is sometimes described as an elegy, filled with an almost palpable sense of nostalgia, resignation, and yet, at times, quiet optimism. It represents a musical reflection on the fragility of life and the passage of time, and it is regarded as a crowning achievement of Schubert’s career. It is a late masterpiece, one of the most emotionally profound and structurally sophisticated works in the piano repertoire.

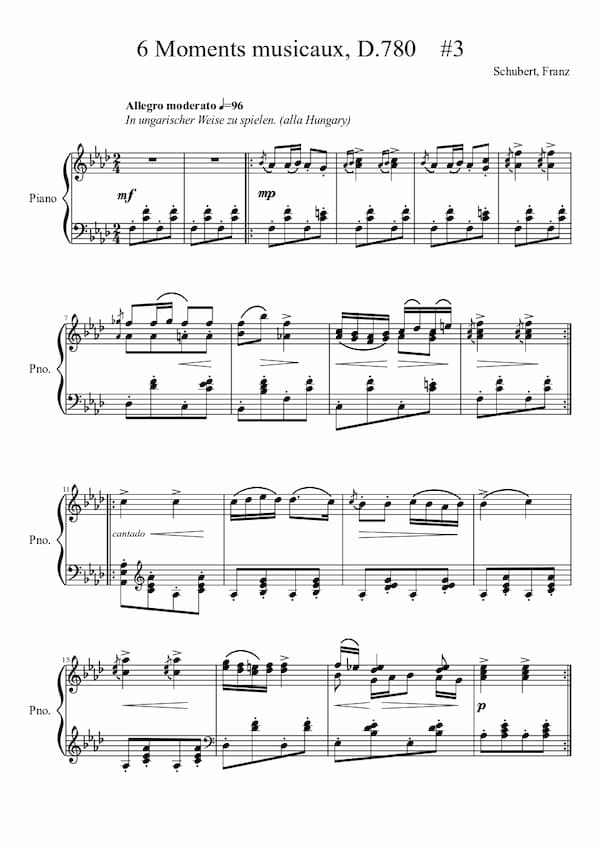

Moments Musicaux, Op. 94 No. 3

Schubert composed the “Moments Musicaux,” actually not his title, in 1827 when he was already dealing with his illness. Despite his health problems, he continued to compose music full of emotional depth, and each piece in the set captures a fleeting moment. The third piece of the set in F minor has an air of contemplation, almost like a musical sigh, and it is often seen as a window into Schubert’s more personal and reflective side.

Schubert’s Moments Musicaux Op. 94, No. 3

Op. 94 No. 3 is scored in a straightforward ABA structure. The opening section in F minor has a melancholy feel, as the mood is calm but carries an undertone of quiet reflection or remembrance. As the key changes to A-flat Major, the mood lightens, and Schubert offers a brief moment of relief. The opening section returns, but with some variations. The overall mood is still melancholy, but there is a sense of acceptance now as if returning to something familiar but with a fresh perspective and deeper understanding.

The piece has an air of contemplation, like a short reflection on a fleeting emotion. It is not overly dramatic but rather quiet and introspective. The music moves through subtle shifts in mood, balancing melancholy with moments of warmth, all while maintaining a gentle and understated elegance. It surely is one of the 10 most popular piano works by Franz Schubert.

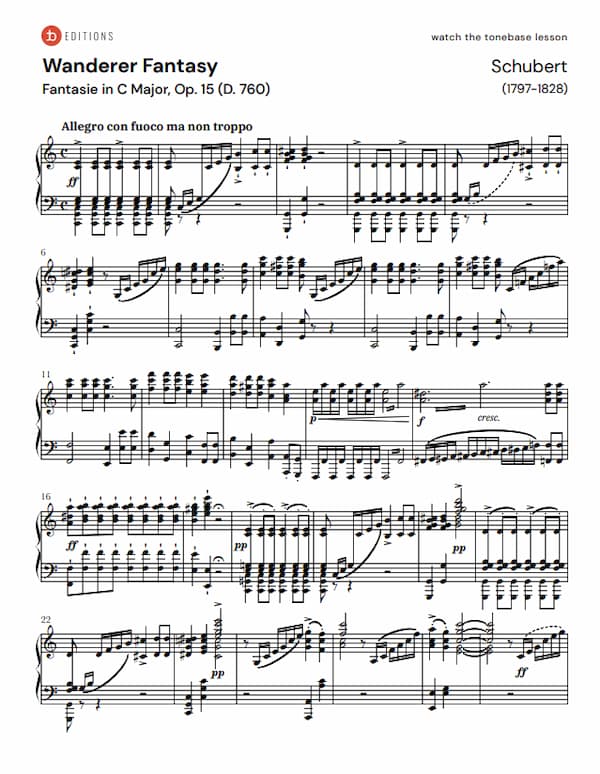

Wanderer Fantasy D. 760

Franz Schubert composed his Fantasie in C Major, nicknamed the “Wanderer Fantasy”, in 1822. It is a vast and ambitious piece that pushes the boundaries of both form and expression. With its blend of lyrical beauty, harmonic richness, and technical complexity, the “Wanderer Fantasy” is a deeply emotional and highly intricate work.

The title “Wanderer Fantasy” is actually referencing the “Wanderer motif,” which appears in many of Schubert’s songs and instrumental works. The image of the wanderer evokes themes of longing and transcendence, and Schubert’s own feeling of alienation brought on by relative obscurity and financial struggles is thought to resonate within the music.

Schubert’s Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy D. 760

The work unfolds in four movements, but it is considered a single large-scale entity unified by recurring motifs. The “Wanderer motif” appears throughout the piece in different guises, harmonically, rhythmically, and contrapuntally transformed. The emotional trajectory is highly varied, with sudden shifts in mood and the portrayal of tension and release. Schubert’s harmonic language is unpredictable, as frequent modulations shift between distant keys, creating a sense of movement and unpredictability. Without a doubt, this is one of Schubert’s most popular piano works.

Impromptu in E-flat Major, Op. 90, No. 2 (D.899)

For our next selection, let us return to the set of Impromptus Op. 90. The E-flat Major piece of the set is known for its grandeur and lyrical warmth. It is often interpreted as one of the most elevated works in Schubert’s piano repertoire. Less introspective than the G-flat Major No. 3, it nevertheless possesses its own unique charm and emotional depth.

The lyrical and flowing theme in E-flat Major is characterised by long and sweeping phrases, and it almost feels orchestral. Schubert introduces subtle contrasts through modulations, enhancing the emotional expressiveness of the piece. The central section is scored in the minor key and sounds more agitated and complex. It is filled with chromaticism and harmonic tension, and the contrast between major and minor and between the lyrical and dramatic, is quintessentially Schubertian.

The return to the opening brings back the original lyrical warmth but it feels much enriched as it is now heard through the emotional contrast of the middle section. There is a gentle and peaceful coda that revisits elements from the opening, but it has become more introspective. Schubert’s expressive lyricism, his sensitivity to harmonic colour, and his mastery of form are all on full display in this work, making it one of the standout pieces in the Op. 90 set and a favourite in the piano repertoire.

Impromptu in A-flat Major, Op. 142 No. 2 (D.935)

Published more than a decade after Schubert’s death, the set of four Impromptus D. 935 actually dates from the year after he had completed his “Unfinished Symphony.” Although these pieces are labelled “Impromptus,” they reach far beyond mere improvisatory charm. They are highly structured and emotionally profound, and demonstrate Schubert’s ability to blend technical brilliance with lyrical depth.

The Impromptu in A-flat Major (Op. 142 No. 2) stands out for its rich, song-like themes, its subtle use of counterpoint, and its dynamic contrasts. The piece has a relaxed, almost conversational quality, but beneath its surface lies a sophisticated exploration of form and harmony, making it one of the gems of Schubert’s piano repertoire.

The piece is a perfect balance of lyricism and elegance, with an effortless flow that disguises its underlying harmonic complexity. The piece moves from the warmth of the opening theme to the lively contrast of the B section before returning to the familiarity of the opening melody, enriched with new nuances. The coda provides for a peaceful resolution. Schubert blends spontaneity with deep emotional resonance and structural sophistication; it’s a miniature masterpiece!

Sonata in A Major, D. 959

Like D. 960, the Piano Sonata in A Major, D. 959 was composed in 1828, shortly before his untimely death in the same year. It is part of a pair of monumental piano sonatas as both reflect Schubert’s deep maturity as a composer. Both display profound emotional depth, innovative harmonic progressions, and an intimate, lyrical style. D. 959 stands out for its elegance and sense of balance, juxtaposing light-hearted and classical elements with moments of profound lyricism and subtle harmonic complexity.

This sonata stands out for its lyrical richness and melody beauty. The harmonic language is rooted in Classical tradition, however, Schubert pushes all the boundaries. Shifts between major and minor modes and unconventional key relationships greatly enhance the emotional depth of the work. Schubert combines Classical forms like sonata, menuetto, and rondo with innovative developments and expressive contrasts. Despite moments of grandeur, the sonata retains an intimate, personal character, with subtle nuances and dynamic contrasts that invite deep reflection.

Surely one of the 10 most popular piano works by Franz Schubert, D. 959 is a beautiful example of his late style, combining lyricism, harmonic sophistication, and thematic inventiveness. With its graceful menuetto, elegiac second movement, and jubilant finale, this sonata is one of Schubert’s crowning achievements. Its warmth, depth, and emotional range continue to captivate pianists and audiences alike.

Moments Musicaux, Op. 94 No. 6

I think we can safely feature one more Moments Musicaux, specifically Op. 94 No. 6 in A-flat Major. It is a delightful work that blends lyrical beauty, subtle harmonic twists, and an almost improvisatory character. It reflects Schubert’s deepening sense of introspection and his mastery of melody, yet it retains a certain lightness that is almost playful at times.

The melody has a singing, almost vocal quality. Its long, lyrical phrases are reflective of Schubert’s ability to craft deeply expressive lines. The melody is sweet and flowing but not without moments of chromaticism that lend a bittersweet edge to the otherwise peaceful character of the piece. However, it isn’t a melody that reveals all of its meaning immediately; instead, it invites the listener to explore its varied shades that often mirror a poetic, emotional landscape.

Franz Schubert

Schubert also provides a particularly engaging harmonic language. While the A-flat major key gives the piece a rich, warm colour, Schubert subtly shifts between major and minor modes and introduces some unexpected harmonic turns. These moments provide emotional depth without disrupting the overall calm atmosphere. Although it is not overtly dramatic or technically demanding, it feels like a brief but meaningful moment in time.

Sonata in G Major D. 894

As with all Schubert’s late piano sonatas, D. 894 is often noted for its intimate, almost introspective character. It does not showcase a grandiose or virtuosic techniques but emphasises inner depth and provides a subtle personal connection with the performer and listener. With its lyrical melodies, rich harmonic textures, and emotional depth, this sonata blends classical form with the emerging Romantic sensibilities of Schubert’s time.

Robert Schumann called the G-Major Sonata “a poem in the form of a sonata.” This poetic reference highlights Schumann’s view that Schubert’s style was not only about structural mastery but also about emotional expression and lyricism. To Schumann, Schubert’s music seemed to convey an inner world of reflection and feeling, much like the expressions found in poetry.

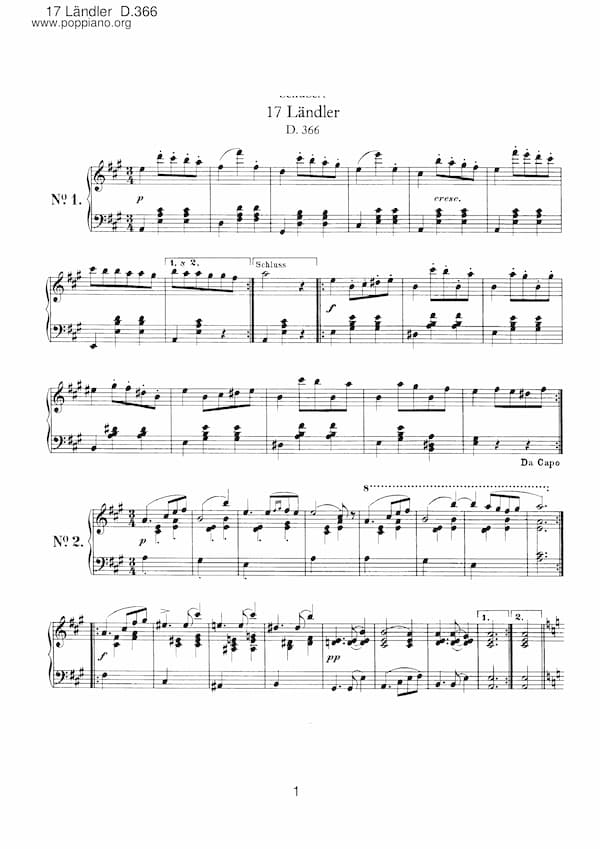

Ländler D. 366

Let us conclude this blog on the 10 most popular piano works by Franz Schubert, with some delightful short pieces often associated with a folk dance. The “Ländler” is a traditional Austrian dance that was a precursor to the waltz, a dance with a slightly rustic feel. Schubert composed a substantial number of “Ländler” throughout his life, either as part of larger piano works or as standalone pieces. These pieces show Schubert’s deep connection to Austrian folk music, which was a key influence in his compositions.

Schubert’s Ländler D. 366

Schubert’s “Ländler” are beautiful examples of how a simple folk dance can be transformed into something rich, nuanced, and emotionally resonant. With their infectious rhythms, graceful melodies, and subtle harmonic depth, Schubert takes what might be seen as a humble dance form and elevates it into a moment of emotional reflection. These miniatures are windows into the emotional life of the composer, tinged with both joy and a quiet sense of melancholy.

I hope you enjoyed this little survey of the most popular piano works by Franz Schubert. Which ones are your favourite, and could you let us know which one should have been included?