by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

On 14 November 1849, Ludwika Jędrzejewicz opened an envelope.

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz

Ludwika Jędrzejewicz was having a bad month. Her marriage was in shambles because she had left Poland to be at her brother Frédéric Chopin’s deathbed.

She had just attended his final illness and funeral and was going through his papers and other personal effects.

She was even preparing to smuggle his heart in a cognac bottle underneath her coat so it could be buried in Poland.

It turns out that the envelope had been sent by no one other than Franz Liszt.

Inside was a questionnaire full of various inquiries about Chopin’s life. Liszt wanted the answers because he was interested in writing a book about Chopin’s life.

On top of the inconsiderate timing, Liszt had included personal questions about her brother’s love life, such as his multi-year liaison with authoress George Sand.

It is believed that the gesture irritated her – or at the least overwhelmed her. She didn’t know what to do with the envelope, so she gave it to Jane Stirling, the wealthy woman who had been serving as Chopin’s concert agent and secretary and who had subsidised Jędrzejewicz’s travels and Chopin’s large funeral.

The fastidious Jane Stirling returned Liszt’s questionnaire to him, but she brushed over some facts in the process. Ultimately, Liszt never used Stirling’s answers.

The First Liszt/Chopin Meetings

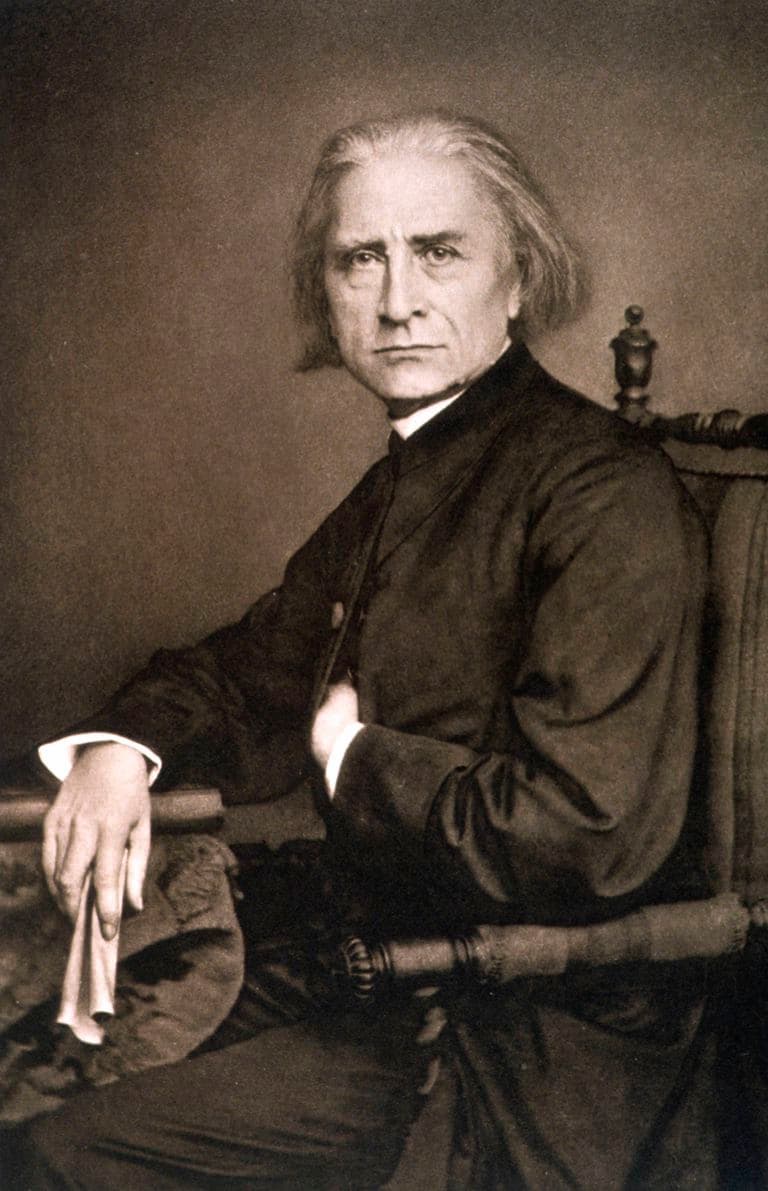

Franz Liszt in 1870

Franz Liszt had known Chopin for many years.

We don’t know when exactly they met, but in December 1831, Chopin wrote a letter to his best friend back in Poland suggesting that he had met Liszt. Liszt would have been twenty and Chopin almost twenty-two at the time.

A few months later, Liszt was in the audience for Chopin’s Parisian debut, which happened at the Salle Pleyel in February 1832.

“We remember his first appearance in the salons of Pleyel, where the most enthusiastic and redoubled applause seemed scarcely sufficient to express our enchantment for the genius which had revealed new phases of poetic feeling and made such happy yet bold innovations in the form of musical art,” Liszt wrote years later in his biography.

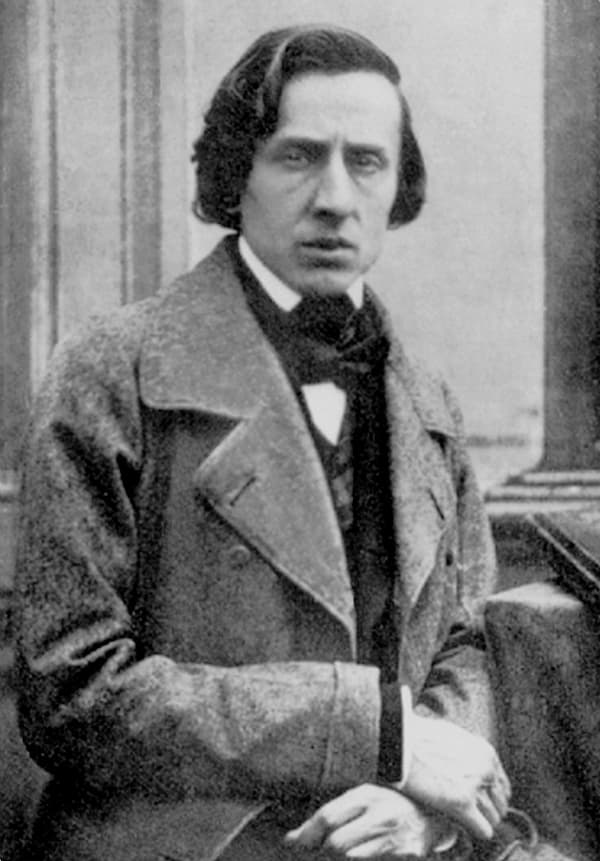

Frédéric Chopin

The two young men became friends and eventually near-neighbours, living a few blocks apart.

They also made a splash performing together in Paris. (Their debut as a duo happened in 1833 at a benefit concert for the bankrupt Harriet Smithson, the actress who Hector Berlioz had written his Symphonie Fantastique and who had since become his fiancée.)

However, they went through their rough patches, too. In 1835, Liszt asked Chopin if he could borrow his apartment while Chopin was away. Chopin agreed. When he returned home, he found out that Liszt had used it for an amorous encounter with the great pianist Camille Marie Pleyel, who had just separated from her husband on account of her infidelities.

On a professional note, there was a certain amount of jealousy, too. Chopin once wrote to a friend, “I should like to rob [Liszt] of the way he plays my studies.” However, he also protested against the way that Liszt added improvisatory elements to a performance of one of his nocturnes. Chopin was so upset that Liszt had to apologise.

Liszt and Chopin’s Romantic Interests

Portrait of Marie d’Agoult by Henri Lehmann, 1843

In 1836, Liszt and his lover, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, hosted a party that would prove fateful to Chopin.

The countess was a great fan of Chopin and extended an invitation to him. She also invited another friend, the radical writer Aurore Dupin, better known by her pen name George Sand, who was arguably the most popular writer in Europe.

Although Chopin was initially put off by the strong-willed Sand, the two eventually fell in love and were a couple for ten years.

Not long after Chopin and Sand paired up, Liszt and the Countess Marie d’Agoult had a protracted and acrimonious breakup.

His next long-term partner was a woman named Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, an unhappily married noblewoman who fell in love with Liszt and remained his partner for forty years. Sayn-Wittgenstein was an extremely prolific author and letter writer, and she encouraged Liszt to also focus on writing, both prose and music.

The Origins of the Chopin Biography

Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

It is believed that after Chopin’s death, Liszt and Sayn-Wittgenstein worked together on the manuscript of the Chopin biography.

The biography began appearing in installments in La France Musicale in 1851.

It turns out that the book was a bit of a disaster. The worshipful Jane Stirling, for one, wasn’t satisfied with how Liszt had described her former boss’s musicianship.

Meanwhile, his Polish friends and family were upset that a non-Pole had published a biography before them, gotten the subtleties of Chopin’s Polish identity wrong, and sucked up all the oxygen in the room when it came to the subject of a Chopin biography. It would be difficult, they believed, for a work by one of them to be taken more seriously than one by Franz Liszt, the internationally renowned musical celebrity…and they were probably right.

George Sand offered her measured thoughts about Liszt’s biography of her ex: “a little exuberant in style but filled with good things and very beautiful pages,” she allowed.

In 1879, Liszt and Sayn-Wittgenstein returned to the project, creating an even longer version, this time, with additional emphasis on Polish politics and identity.

Sayn-Wittgenstein was apparently the driver behind many of the changes, and unfortunately the changes – and her turgid writing style generally – has proven to be unpopular with modern scholars and historians.

The Biography’s Legacy

Life of Chopin by Franz Liszt

Of course, given Liszt’s fame, some of the facts in his biography were distributed in other later biographies.

One of the ideas that gained traction was Chopin’s perceived aristocratic nature.

For instance, it was reported in Liszt’s book that Chopin’s education had been financed by Prince Radziwill (it had not been) and that the friends who he spent the most time with were members of the Polish aristocracy (they were not).

Conclusion

Today, the historians brave enough to wade into the messy, complicated subject of Liszt’s Chopin biography generally believe that while the biography is a helpful document for understanding how Liszt and his Parisian contemporaries viewed Chopin, there’s much about it that’s misleading or even flat-out wrong.

That said, as long as you keep all of that in mind, it’s definitely worth a read, as the English translation has long been in the public domain. So why don’t you download a copy and see what you think?