by

Music is a powerful means of communication, by which people share emotions, intentions, and meanings, and our personal engagement with music, whether in a live concert, listening to a CD or via a streaming service, is driven by the medium’s ability to convey and communicate emotion. Music can arouse strong feelings, recall memories; it can promote extreme happiness or engender feelings of deep love or loss…

Like speech, music has an acoustic code for expressing emotion, and even if a piece of music is unfamiliar, we can “decode” its message. Because of this, while musicians perform music according to their own interpretations, we can still understand the basic acoustic code: a crescendo indicates increased intensity or drama; a minor key suggests seriousness or melancholy; pauses create suspense and anticipation.

For the performer, the ability to communicate emotion, or tell a story, in music requires more than the technical facility to process what’s on the score. A good understanding of the structure of the music is important for a convincing, and communicative, musical performance, allowing the musician to respond to aspects such as variations in tempo and dynamics, harmonic and melodic tension and release, phrasing, repetitions, etc. By responding to these elements, the listener is given a set of musical “signposts” which guide them through the music, and bring cohesion, interest and variety to the performance.

A performer must resolve the entire depth of the ideas contained there. How often carefully notated shadings, accents, tempo changes reveal not simply a positive characteristic of sound but rather the untold sides of the author’s concept. How many directions we find in Schumann, Chopin, Scriabin, even Beethoven that a pianist should follow not in a real sound but by addressing the subtlest hints to the imagination of a listener!

– Samuil Feinberg

Communicating emotion is the most elusive aspect of the performer’s skillset, and is the fundamental reason why people – performers and listeners – engage with music. At a basic level, music communicates specific emotions through simple musical devices, for example:

- Happy – fast tempo, running notes, staccato, bright sound, major key

- Sad – very slow tempo, minor key, legato, descending sequences or falling intervals, diminuendo, ritardando

But there is something else which makes a performance particularly rich in expression or communication. Performance is generally regarded as a synthesis of both technical and expressive skills. Technical skills can be taught, while expression is more instinctive: it is of course possible to act upon expression markings in the score, but in order for these to sound convincing and, more importantly, natural, the performer must draw upon other factors, including extra-musical ones.

Many performers create a vivid internal musical and artistic vision of the music they are playing. This may include an aural model; the use of metaphors or adjectives to create a narrative or picture for the music; and personal experience, including extra-musical experiences. A performer’s own emotional experiences may influence the way they convey emotion in the music. This suggests that only a performer who has actually experienced the highs and lows of romantic love can perform, for example, Schumann’s Fantasie in C with the requisite emotional insight. Of course, not every performer will have the life experience, but they can still convey emotion in their performance by awakening their imagination to bring expression and emotional depth to their playing. In addition, in a concert situation, the imagination of the listener is very much at the disposal of the performer, to be shaped and influenced through sound.

We talk about performers “communicating the composer’s intentions” (i.e. paying attention to and acting upon directions in the score such as dynamics, tempo and expression markings, articulation, rests and pauses etc) or “conveying the story of the music“, but fundamentally I think as listeners we crave a performance which touches us personally. Listening to music is a highly subjective and personal experience – we’ve all had those ‘Proustian rush’ moments when a piece of music, or a single movement or even a phrase, provokes an involuntary memory, sometimes with physical side-effects such as goosebumps or shivers (physiologically, this is the result of the release of Dopamine, the brain’s “reward” neurotransmitter). Sometimes we want to feel uplifted or transported by music, taken us out of ourselves and the mundanity of everyday life to another place, to experience something touching the spiritual or transcendent. Such moments, and the memory of them, are very special and individual.

Occasionally one is at a concert where a very palpable sense of collective concentration can be felt in the auditorium. This occurs when the performer creates an intense communication between music and listener. I experienced it, along with the rest of the Wigmore Hall audience, at a performance of Beethoven’s last three sonatas by the Russian pianist Igor Levit in June 2017. The sense of concentrated listening and suspense was extraordinary. How did Levit achieve it? I’m not sure…. a combination of exquisite tone control, musical understanding and the sheer power of the music itself.

Most people like music because it gives them certain emotions such as joy, grief, sadness, and image of nature, a subject for daydreams or – still better – oblivion from “everyday life”. They want a drug – dope -…. Music would not be worth much if it were reduced to such an end. When people have learned to love music for itself, when they listen with other ears, their enjoyment will be of a far higher and more potent order, and they will be able to judge it on a higher plane and realise its intrinsic value.

– Igor Stravinsky

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years.

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years. In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with

In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with  In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel,

In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel,  As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is

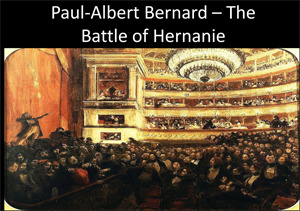

As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is  Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.

Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.