by

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years.

Later mythologized as a true Italian, Giuseppe Verdi was born on October 10, 1813 in Busseto as a French subject, which seems to have disturbed him enough to lead him to represent that he had in fact been born in 1814, in which year the Dukedom of Parma, to which Busseto belonged, became an independent Italian state. Throughout most of the 19th century, Italy was not a political entity, but rather a cultural idea, where everyone, whether in Milano, Venice, Genoa, in the Piedmont and in the many other cities and states, could live as a member of an ancient, noble and respectable cultural community, irrespective of borders, customs and tariffs. A political union had been impossible, since the major European powers — Germany, Spain, France and Austria, as well as the Papal States — controlled the various Italian regions. The 19th century saw a re-awakening, the ‘risorgimento’ as it would later be called — a cry for political unity and independence, whose most outspoken representative was the writer Vittorio Alfieri, whom Verdi very much admired. Alfieri conceived Italian nationalism as a spiritual/political idea of liberation and freedom, a concept which became the focus of various political movements in the following years.

The Italian Root of Giuseppe Verdi

In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with Vivaldi, Salieri and many others, was the Italian musical capital per se. In the 19th century, even though Italy was not a single national political entity, opera brought people together. Italian masters, Rossini from Bologna, Bellini from Catania and Donizetti from Bergamo, were successful in all of Europe and brought Italian opera to the North.

In Italy, even language divided the different Italian regions, in which everyone spoke the specific dialect of the district — Italian as such was used only as a written language and was unfamiliar to most. The only languages everyone did understand, were those of music and poetry, such as that of Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso. Music and opera made it possible for every Italian to be part of this nation of culture, a unity of the people. Music, as the true expression of feelings, of the heart, of passions, could therefore be considered the true language of the people. Already in earlier centuries, Italians knew that they were a European musical power, for example with Cherubini in Paris and Spontini in Berlin, and that Vienna, with Vivaldi, Salieri and many others, was the Italian musical capital per se. In the 19th century, even though Italy was not a single national political entity, opera brought people together. Italian masters, Rossini from Bologna, Bellini from Catania and Donizetti from Bergamo, were successful in all of Europe and brought Italian opera to the North.

Verdi was very much influenced by Italian republican ideas — he named his children Icilio and Virginia after idealized Republican Roman heroes — but he also made sure not to offend the Austrian authorities by openly supporting the regional independence movements.

While working in Milano in 1832, which at that time was still under Austrian command, he not only heard Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and major works of Viennese classical music, but broke his contract to work in Busseto in order to remain in Milano, where his first opera, ‘Oberto’, received a favorable reception.

Nationalism in Giuseppe Verdi’s Operas?

In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel, Goethe, Schiller, Grillparzer and particularly Madame de Staël’s book on Germany (‘De l’Allemagne’). Andrea Maffai was also a member of the ‘Societá dei filodrammatici’, whose focus was to unite opera and drama – an idea Verdi would apply to all of his future operas – just as Wagner was seeking to do. Under the influence of Maffai and his friends, Verdi became one of the Italian composers most knowledgeable about European dramatic literature. The northern ‘high’ aristocratic families, such as the Strassoldo, Colloredo, Pallavicini, Thurn und Taxis as well as many others, had international focus and background — they provided support to artists without consideration of language or nationality. For them, music, and in particular opera, had to be good, with themes that could be presented anywhere — not patriotic political pieces, but great Italian music. Verdi did not think of an Italian nationalistic piece when he composed ‘Nabucco’, but in later years, the choir of prisoners, ‘Va pensiero’, anchored the myth that Verdi had given voice to Italian demands for freedom, unity and independence. Interestingly, nowhere other than in Italy, whether in Vienna, Berlin or Weimar, was the famous choir of prisoners considered as political provocation, and the opera was a great success.

In 1842, again in Milano, Verdi achieved real fame with his opera, ‘Nabucco’, which also saw tremendous success in Vienna in 1843. All of the famous salons in Milano now became open to him, in particular the salon of Clarina and Andrea Maffai (descendants of the Italian/German aristocracy with familial connections to Munich and Salzburg), who introduced Verdi to ‘world literature’, in particular the works of Klopstock, Schlegel, Goethe, Schiller, Grillparzer and particularly Madame de Staël’s book on Germany (‘De l’Allemagne’). Andrea Maffai was also a member of the ‘Societá dei filodrammatici’, whose focus was to unite opera and drama – an idea Verdi would apply to all of his future operas – just as Wagner was seeking to do. Under the influence of Maffai and his friends, Verdi became one of the Italian composers most knowledgeable about European dramatic literature. The northern ‘high’ aristocratic families, such as the Strassoldo, Colloredo, Pallavicini, Thurn und Taxis as well as many others, had international focus and background — they provided support to artists without consideration of language or nationality. For them, music, and in particular opera, had to be good, with themes that could be presented anywhere — not patriotic political pieces, but great Italian music. Verdi did not think of an Italian nationalistic piece when he composed ‘Nabucco’, but in later years, the choir of prisoners, ‘Va pensiero’, anchored the myth that Verdi had given voice to Italian demands for freedom, unity and independence. Interestingly, nowhere other than in Italy, whether in Vienna, Berlin or Weimar, was the famous choir of prisoners considered as political provocation, and the opera was a great success.

Elements of many of his other works, such as parts of Ernani, I Lombardi, Don Carlos and Macbeth, were also later seen by Italians as the voice of the people protesting foreign dominance, although Verdi himself made no such connection. Unlike Wagner, who had actively participated in the 1848 revolution in Dresden, Verdi saw the various Italian political attempts at liberation and reunification from afar –(i.e., the revolutions of 1830, 1848, 1861, 1866 and finally, the unification of Italy in 1871) — from Paris or from his luxurious country estate in Roncole. In his personal letters, he expressed his interest in Italian political matters, but what most interested him was the financial success of his operas and his friendships throughout Europe. Italy was and remained for him a cultural idea, an idea of Italian art, music and way of life.

Can Giuseppe Verdi Be Considered a True Romantic?

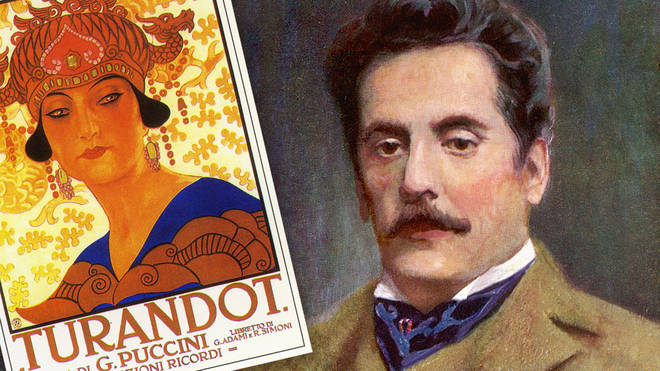

As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is Puccini’s ‘Tosca’, which starts with the meeting of the protagonists in church and ends with the execution the next morning, again 24 hours. Virtually all classical plays and operas would follow these rules.

As I have mentioned before, Verdi was very familiar with the ‘classical’ works of Shakespeare, the ‘romantic’ works of Victor Hugo, Lord Byron and Alexandre Dumas and based many of his operas on their works. Interestingly, Shakespeare had been rediscovered by the French Romantic painters and writers in the 19th century, who saw him as a revolutionary playwright. In his plays, Shakespeare had never adhered to, and had broken, with the classical French dictum of the ‘unity of time, action and space’, where all stage performance had to adhere to the 24-hour rule, i.e. that all the action on stage had to be started and completed within a 24 hour day. In opera, one such example of the rule is Mozart’s ‘Abduction from the Seraglio’, where the action starts with the abduction and ends with the resolution and celebratory meal 24 hours later. Another example is Puccini’s ‘Tosca’, which starts with the meeting of the protagonists in church and ends with the execution the next morning, again 24 hours. Virtually all classical plays and operas would follow these rules.

Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.

Verdi used Victor Hugo’s play ‘Hernani’ as the basis for his opera by the same name. In 1830, Hugo’s ‘Hernani’ had its first Paris performance as the first Romantic play, and had met with fierce opposition from the French audience, although valiantly defended by Hector Berlioz, Théophile Gautier and many of the French Romantic writers and painters. Hugo had broken all of the classical rules — the locale and action in his play changed often and they exceeded the 24 hour day. Composed in 1844, Verdi insisted that his opera libretto follow Hugo’s play as closely as possible, and so, in Act I, the action is situated in the mountains of Aragon; in Act II, in Don Ruy Gomez Castle; in Act III, in Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen; and in act IV, back to Spain, in Saragossa. The opera also shows the young Verdi honing his operatic skills in creating dramatic tension (three men pay court to one woman), with the conspiracy scene, its evocative orchestral coloring, and in general, the lyrical fervor of his arias (‘Ernani… Ernani involami’; ‘Vieni meco, sol di rose’, etc.), setting the new standards for Romantic operas — Italian style.

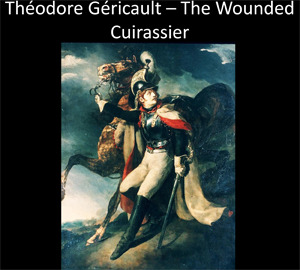

In the 19th century, we not only see the change from the Classical to the Romantic canon in theatre and music, but also in painting. Verdi continued his successes with ‘Rigoletto’ (based on Victor Hugo’s, ‘Le Roi s’amuse’), ‘Il Trovatore’, and ‘La Traviatia’ (based on Alexandre Dumas’ play ‘La dame aux camélias’). All three operas can be seen as Verdi’s supreme achievement of the Romantic Italian melodrama, and we can consider him a true Romantic — but not a true Revolutionary.