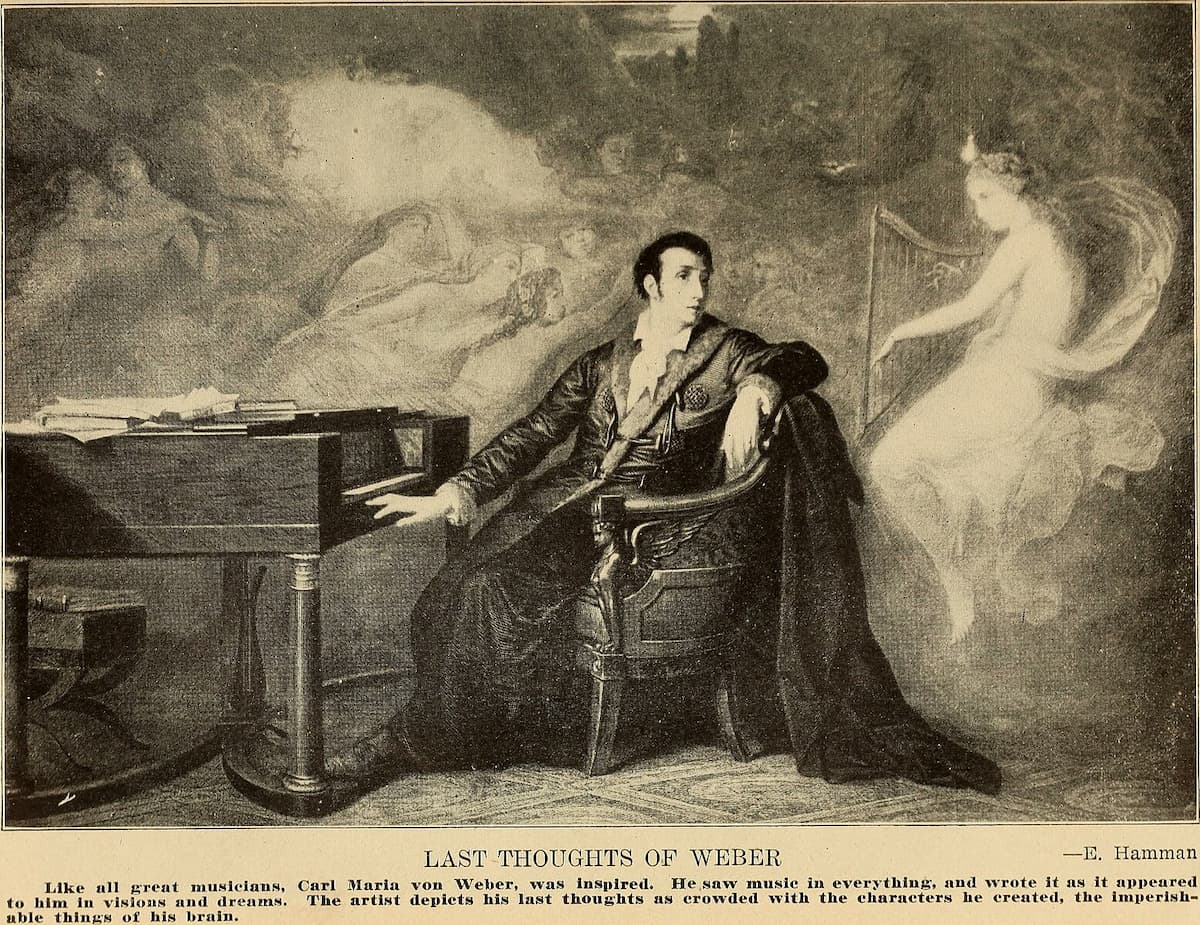

Last Thoughts of Carl Maria von Weber, by Edouard Hamman

Carl Maria von Weber left us four piano sonatas, all composed between 1812 and 1822. These works are considered the pillars of his piano oeuvre. As we remember his all too early death in early June 1826—he was only 39 years old—let us explore Carl Maria von Weber, the pianist. To get us started, here comes his arguably most famous piece, the delightful Invitation to the Dance.

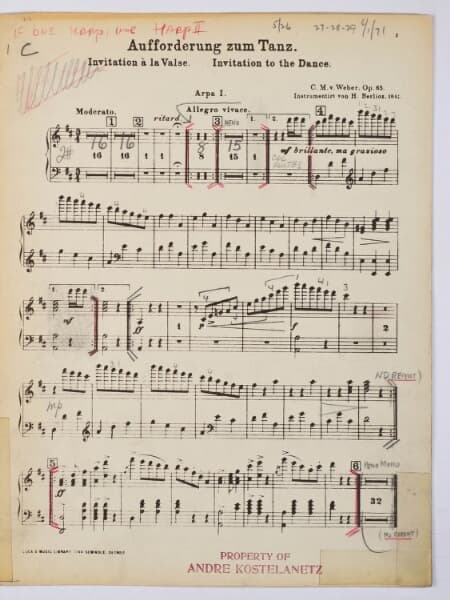

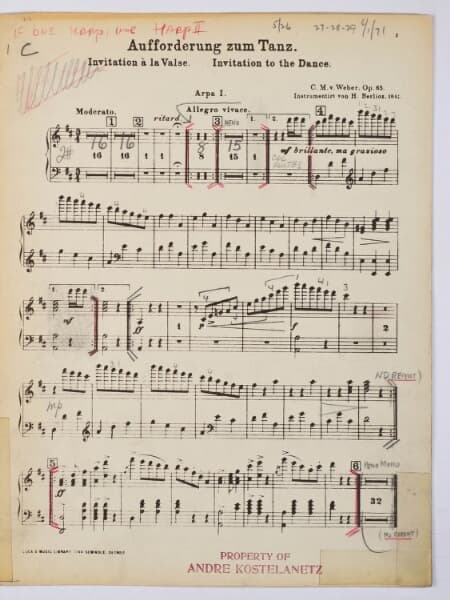

Carl Maria von Weber: Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65

Weber came to the piano sonata relatively late in the game. He was twenty- six when he composed his Sonata No 1 in C major Op. 24 in early 1812. While he was still working on his first two works, his contemporaries had already published a substantial number of piano sonatas. Clementi, for example had already seventy piano sonatas to his name, Dussek had published thirty-five, Hummel four, and Beethoven had already introduced 27 sonatas to the public.

Carl Maria von Weber: Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 24

The young Carl Maria von Weber

From the very beginning it was obvious that these works offered some serious technical demands. Weber apparently attempted to teach his 1st sonata to the talented dedicatee, the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Weimar, but she could not master it. To be sure, the opening “Allegro” is a grand and stately affair, clearly designed to show off the technical skills of the performer.

One of the reasons the Weber sonatas are technically challenging lay in the size of Weber’s hands. His student Julius Benedict wrote that Weber was “able to play tenths with the same facility as octave, and that he produced the most startling effect of sonority, and possessed the power to elicit an almost vocal tone where delicacy or deep expression were required.” We can hear some of that vocal tone in the “Adagio” from the 1st Sonata, as the music resembles a highly embellished operatic aria.

To have large hands like that was certainly an advantage for Weber. As a matter of fact, he incorporated flashy scales and arpeggios, toccata-like double notes, daredevil leaps, and driving rhythms that could impart a sense of dramatic passion. Weber called the third movement “Minuetto,” but in character, it is clearly a playful and majestic scherzo.

It seems that Weber actually wrote his 1st piano sonata in reverse order, starting with the finale. Weber himself called it “L’infatigable,” and Alkan gave it the title “Perpetuum mobile.” It’s an exciting whirlwind of perpetual motion and it became so popular that many pianists arranged it for use. Brahms arranged it as a study for the left hand, Tchaikovsky made a left-hand arrangement and composed a new right hand, and Henselt revised it with additional difficulties. And there are arrangements by Czerny and Godowsky as well.

Carl Maria von Weber: Piano Sonata No. 2 in A-flat Major, Op. 39

Weber’s Piano Sonata No. 1, according to a contemporary, contained “surprises at every turn. Forms, textures, colorations and other elements are contrasted and brought into balance with the virtuosity of a young master—orchestrating at the keyboard with a skill not unlike Beethoven’s.” The Sonata No. 2 in A-flat Major, Op. 39 was written in two separate periods, and also written backwards. Apparently, Weber started with the concluding “Rondo” and then worked his way backward to the first movement.

Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Dance orchestra score

Weber started the work in Prague, where he worked as Kapellmeister of the theatre, and Berlin. He moved to Berlin to be with his fiancée, the soubrette Caroline Brandt who had landed a singing engagement. Weber’s student Julius Benedict reports that “the composer was wrapped up in the love of his future partner for life,” when he wrote the sonata. We can certainly sense this intimate sentiment and spacious grace of human love in the opening movement.

To Benedict, Weber’s Op. 39 was “the grandest and most complete composition of the master because of its originality of form, deep pathos and poetical feeling.” It is a homogeneous composition with a vastly different inner life than the extroverted Sonata No. 1. It was much admired by Chopin, who had his students practice it, and Liszt had a personal copy of the score. Tchaikovsky orchestrated the “Minuet,” and Alfred Cortot fashioned a very useful study edition of it in 1930. The only person hating it was the dedicatee, an unknown Berlin gentleman by the name of Franz Lauska.

We don’t know a lot about Weber the pianist, but in February 1812 he went to Dresden to give a couple of concerts. The reception was mixed, as critics judged that “his playing style is essentially an imitation of Spohr, and that his music reveals a strange and false conception of harmony.” The reason for such a devastated assessment was to be found, according to the composer’s father, in the fact that “Dresden‘s high society has not the slightest interest in artists unless they are Italian.” As elsewhere, Rossini was the toast of the town and Weber’s curious assemblage between skilfully crafted Italian arias and a learned Germanic language caused some confusion indeed.

Carl Maria von Weber: Piano Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 49

Carl Maria von Weber composed his Piano Sonata No. 3 in D minor Op. 49 in 1816. In fact, it was written in just twenty days of feverish inspiration. The work is not particularly popular with pianists or musicologists, who view it “as little more than the successful manifestation of a gallantly courtly Romanticism and particularly brilliant writing technique.” It is certainly different from his Sonata No. 2 in that it is cast in three traditional movements and features skillful counterpoint in the outer movements. It is darker, more dramatic, and almost reminiscent of Beethoven in terms of mood.

Carl Maria von Weber cigarette trading card

This sonata seems less pianistically conceived, as Weber explored new ways of developing his themes through counterpoint, with all three movements looking towards orchestral sonorities and textures. The opening “Allegro” is close to Beethoven as it is based on the conflict between two successive themes. First there is a fortissimo march which is contrasted by a gentle and elegiac opera cantilena.

And the central “Andante” exploits a theme in five variations, bringing vocal improvisation to the keyboard. Just listen to the cadenzas, recitatives and the abrupt changes of key. The concluding “Rondo” sounds Schubertian to me, as delicious melodic ideas closely follow one another. There are no extra-musical connections in this work so it’s just a classically abstract sonata; what a fascinating composition.

Weber took almost three years to produce his final Piano Sonata No. 4 in 1822. He was now a much more seasoned composer, and he attempted to maximize the technical, sonic, and expressive potential in his piano music. In his earlier works, he has taken over all the typical virtuoso techniques of the period around 1800, including scales, arpeggios, double notes, trills, and octaves, “but his search for new techniques and sonorities led to features that set his pianism apart from the brilliant style of Hummel and other virtuosos.”

According to a number of pianists, these new techniques were based on rapid arm movement, including octave glissandos, fast staccato chords, and leaps, and “widely spaced chords in the left hand for a fuller sonority, tremolos, and the combination of legato melody and staccato accompaniment in one hand.”

Carl Maria von Weber: Piano Sonata No. 4 in E minor, Op. 70

The opening “Moderato” appears to have originated with a bad performance of some incidental music. Benedict claimed that, “the first movement, according to Weber’s own ideas, portrays in mournful strains the state of a sufferer from fixed melancholy and despondency, with occasional glimpses of hope which are, however, always darkened and crushed.” We can certainly sense Beethoven’s shadow once more, particularly in its motific development of the movement.

The almost melancholy character of the opening of the first movement is contrasted not by a slow movement, but by a “Menuetto.” This sonata was composed simultaneously with the great operas Der Freischütz and Euryanthe, and it is certainly full of contrasts. However, the nervously driving “Menuetto” does not sound like either of the operas, nor like any of the preceding sonatas. Weber had discovered a new pianistic idiom, although it is still easy to imagine Weber and his enormous hands tickling away at the keyboard.

Caroline Bardua: Carl Maria von Weber, 1821

The slow movement is true Weber, as he presents a simple folk style tune. Consolatory in nature, it “expresses the partly successful entreaties of friendship and affection endeavouring to calm the composer, though there is an undercurrent of agitation and evil augury.” In the concluding “Tarantella” the model once again seems to have been Schubert and “an almost lieder-like delicacy of expression.”

This sonata is dedicated to the critic J.F. Rochlitz, who very much liked the two preceding works. Looking over Weber’s four sonatas, there is a gradual process of moving from dazzling virtuosity to a more reflective and less showy style. The 4th Sonata is still very challenging to perform, but the substance comes from multiple strands of counterpoint and a growing sense of orchestral texture. As a scholar wrote, “Weber’s genius lay in unifying form, content, and expression with telling effect.”

Carl Maria von Weber: Grande Polonaise in E-flat Major, Op. 21

I’ve started this blog by playing Weber’s charming Invitation to the Dance, so it seems fitting to conclude with a Grande Polonaise. Both programmatic pieces and his sonatas readily attest to Weber’s unique manner of pianism. Generally, he elicited mostly enthusiastic responses from the audience. After appearing on stage in 1810, “his reputation as an eminent pianist spread like wildfire. So great was the curiosity excited, so overwhelming the crowd which flocked around him, so startling the marks of homage and reverence lavished upon him that he began to grow weary of what he called his undeserved honours.”

But back to the Grande Polonaise, Op. 21. Weber wrote it for the singer and actress Margarethe Lang in 1808. She was the daughter of the Munich violinist Theobald Lang, and according to Weber Sr. “a plump, seductive little figure and a fund of sprightly, charming humour.” Weber was besotted and he constantly sought her company, neglected friends and official duties. Eventually, he wrote a musical portrait of his infatuation, the Grande Polonaise. That truly another invitation to a “dance,” don’t you think? Of course, at the piano with Carl Maria von Weber also includes 2 Piano Concertos and a Concertück, but that’s a topic for another blog.