It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, April 26, 2024

Discover Margaret Bonds

By Fanny Po Sim Head, Interlude

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

And my throat

It is deep with song

You do not think

I suffer after

I have held my pain

So long?

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry?

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing

You do not know

I die?

These are Minstrel Man’s lyrics, the first piece of Three Dream Portraits composed by Margaret Bonds. I discovered Bonds through playing this piece for a singer. The emotional text accompanied by a relatively straightforward piano part creates a powerful effect and led me to want to know more about her and her music.

Margaret Allison Bonds

Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) was born in Chicago, the United States. Her parents, Estrella Bonds and Dr. Monroe Majors were divorced when Margaret was very young. While her mother and her grandmother raised Margaret, she remained close with her father. Dr. Monroe Majors (1864-1960) was a physician, a writer, and a civil rights activist. He opened one of the first black hospitals in Texas. One of his popular publications, Noted Negro Women: Their Triumphs and Activities, acknowledges the accomplishments of black women since the end of slavery in the 1860s. Margaret had once collaborated with her father for his campaign song We’re All for Hoover Today.

Margaret Bonds took piano lessons from her mother when she was little. Estrella Bonds was a renowned piano teacher. She was also a charter member of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM). Margaret Bonds grew up meeting many African American artists and literary figures, including Abbie Mitchell, Will Marion Cook, and prominent female composer Florence Price (1887-1953). Bonds composed her first work, Marquette Street Blues, at the age of five. In addition to taking piano lessons, she took composition lessons from Florence Price and William Dawson (1899-1990) before going to Northwestern University, a traditionally “white” college.

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Bonds completed both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music at Northwestern University. During her studies, her song Sea Ghost won the Wanamaker Prize’s vocal category (1932). Also skilled as a professional pianist, she was the first African American woman to perform as a soloist with a major American orchestra. In 1933, she served as a solo pianist with the Chicago Symphony orchestra, playing John Alden Carpenter’s Concertino for piano and orchestra. In 1934, she performed Price’s Piano Concerto in D minor with the Women’s Symphony Orchestra. The same year, she finished her master’s degree at Northwestern University.

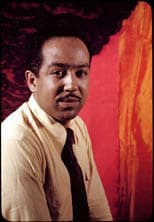

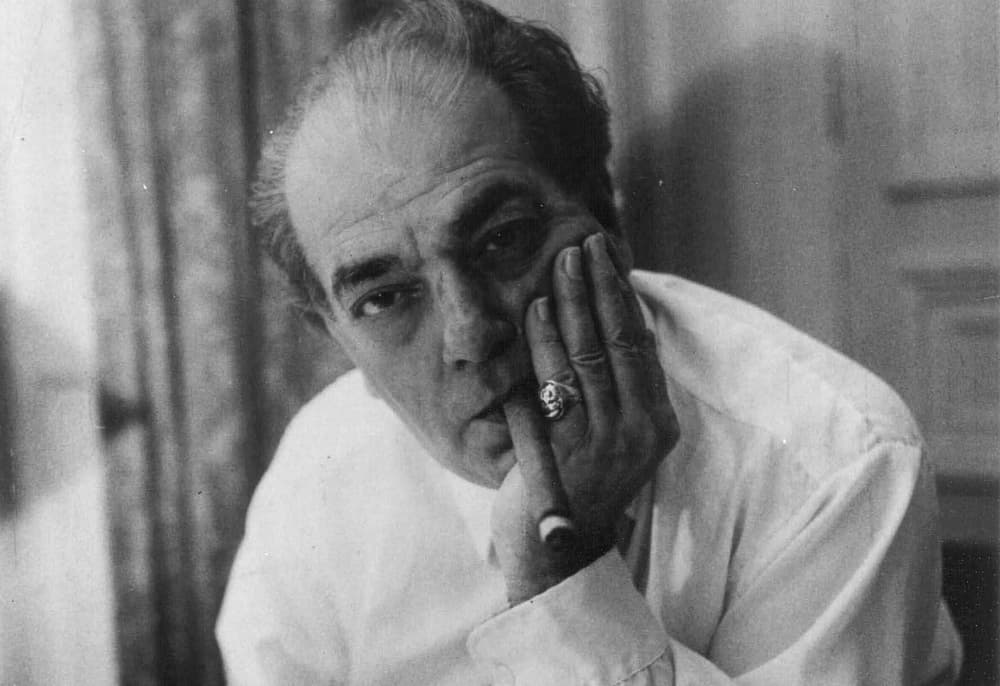

Langston Hughes © Carl Van Vechten / Carl Van Vechten Trust / Beinecke Library, Yale

In 1939, Bonds received a scholarship studying composition with Roy Harris (1898-1979) at the Julliard School of Music. She moved to New York, living in the historically black neighborhood of Harlem. She met her husband, Lawrence Richardson, through Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes (1902-1967), a prominent poet and a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, inspired Margaret Bonds in many ways. During her years studying at Northwestern University, Margaret Bonds experienced her first prolonged racism. She found great comfort in Langston Hughes’ signature poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Margaret Bonds discovered more of his works and became more aware of her black heritage. They finally met in person in 1936, and they became lifelong friends and collaborators. According to Bonds’ daughter, Hughes was such a part of the family that he usually stayed at their house during Thanksgiving and Christmas. Soon after their first meeting in 1936, Margaret Bonds began to set his poems into music, including The Negro Speaks of Rivers.

Margaret Bonds devoted herself to elevating African American music and art. By blending the idiomatic musical language of spirituals and work songs, and the increasingly sophisticated vocabulary of jazz with the conventions of the western classical traditions, Bonds sought to re-establish African American culture and art as something complex, beautiful, something essential to the American identity. The collaborations between Langston Hughes and Margaret Bonds include numbers of vocal and choral works and plays.

Ballad of the Brown King

During the Civil Rights Movement, Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes continued to collaborate and emphasize African American culture and values. She composed two significant works dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr., and one of them is the Ballad of the Brown King, which remained one of the most popular and frequently performed pieces of their collaboration. Inspired by the Civil Rights movement, this work was a Christmas cantata in honor of the African king, Balthazar. Premiered in New York in 1954, Bonds extended this short version to an orchestral version with nine movements, and it was performed in 1960 by Westminster Choir. The movements are all related in terms of keys and theme. Their musical styles continue to display Bonds’ trademark of utilizing European compositional technique with African American vernacular music. The 9-movements exhibit a variety of African American musical styles. It ranges from the traditional four-part hymn gospel, spirituals to calypso. Mary had a Little Baby, the fourth movement of the work, became one of the most famous pieces of the Ballad.

Troubled Water

For instrumental works, the majority of them are arrangements of spirituals. Bonds arranged over 50 spirituals into her compositions, and they often feature active and independent lines with expanded and rich harmonies. Troubled Water is perhaps the only published work for solo piano. The last movement of a three-movement Spiritual Suite, Troubled Water, is based on the spiritual Wade in the Water, and the title is probably inspired by its lyrics, “God’s gonna trouble the water.” Essentially a theme and variation, the contrapuntal technique and the overlapping “call and response” pattern once again represent Bonds’ blending of the classical western tradition and African American musical idioms, respectively. Idioms such as syncopation and jazz harmonies are found throughout the entire piece. This piece is full of excitement and drama with a triumphant ending that gets a strong audience response.

Margaret Bonds: Troubled Water

Due to its popularity, Bonds also rearranged Troubled Water for cello and piano, and symphony orchestra.

After Langston Hughes died in 1967, Margaret Bonds left New York and moved alone to Los Angeles. Although she continued to work diligently and kept bringing Langston Hughes’ works to the public, depression and alcoholism continued to affect her life. Sadly, when she passed away, many of her letters, music, and manuscripts were discovered in the dumpster by her house. While some of them are collected and stored in libraries’ archives, most of her work remains unpublished and unheard. The scope of her work and influence is yet to be fully known.

Unique Concertos Works by Glière, Daetwyler, Horovitz, Villa-Lobos, Diemer, and Akiho

By Georg Predota, Interlude

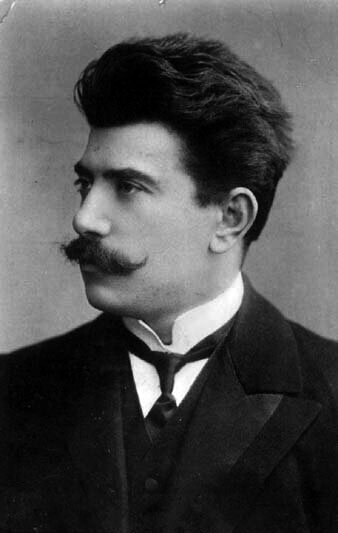

The Young Reinhold Gliére

Composed in 1943, the Concerto in F Minor for Coloratura Soprano and Orchestra unfolds in two movements. Glière does not provide instruction about the type of sounds required, and there are no provisions in the score for actually taking a breath. In the absence of text, musical expression is left entirely up to the soprano. In fact, the whole composition is conceived as though the voice were an instrument of almost limitless possibilities. Composing a concerto for voice is one thing; writing one for Alphorn presents some very special challenges.

Jean Daetwyler: Alphorn Concerto

Jean Daetwyler

The Swiss composer Jean Daetwyler (1907-1994), who had studied with Vincent d’Indy at the Paris Conservatoire, took on that enormous challenge. Traditionally used as a signaling instrument in the alpine regions of Europe, the Alphorn is of phenomenal size. The instrument consists of a straight several-meter-long wooden natural horn of conical bore. The composer writes, “it is very difficult to write music for the alphorn. The instrument, in spite of its size, has only five notes that can be used to write a melody… For me, the alphorn represents solitude, man alone before Nature. With its five notes but above all with its powerful and magnificent sound, the instrument demands of the composer the greatest simplicity in evoking feelings of the deepest truth.”

Alphorns

Joseph Horovitz: Euphonium Concerto

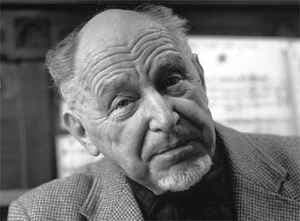

Joseph Horovitz

The non-transposing brass instrument called euphonium was invented in the early 19th century. Its name derives from an Ancient Greek word meaning “well-sounding” or “sweet-voiced.” The instrument was made possible by the invention of the piston valve system, which allowed brass instruments with an even sound the facility of playing in all registers. A number of euphonium variants with either three or four valves were constructed, but the fingerings on the euphonium are the same as those on a trumpet. Often mistaken for a baritone horn, the euphonium produces a darker tone and a gentle sound. It still plays an important role in military and brass bands around the world. While most euphoniums can be played from a sitting position, a slight change in design also allows the instrument to be easily carried while marching. The instrument has always played an important role in ensembles. As such, solo literature was slow to appear and Joseph Horovitz composed the first concerto for the euphonium only in 1972.

The Euphonium and Tuba

Horovitz was born in Vienna in 1926 and emigrated to England in 1938. Throughout his long and productive career, he composed twelve ballets, nine concertos, two one-act operas, chamber music, works for brass and wind bands, film, television and radio, and choral works. His compositions have always been known for their melodic richness, its energy, and its craftsmanship. His Euphonium Concerto set “the benchmark” for future generations of soloists and composers, and Horowitz propelled the euphonium as a solo instrument towards international popularity.

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Concerto for Harmonica

Heitor Villa-Lobos

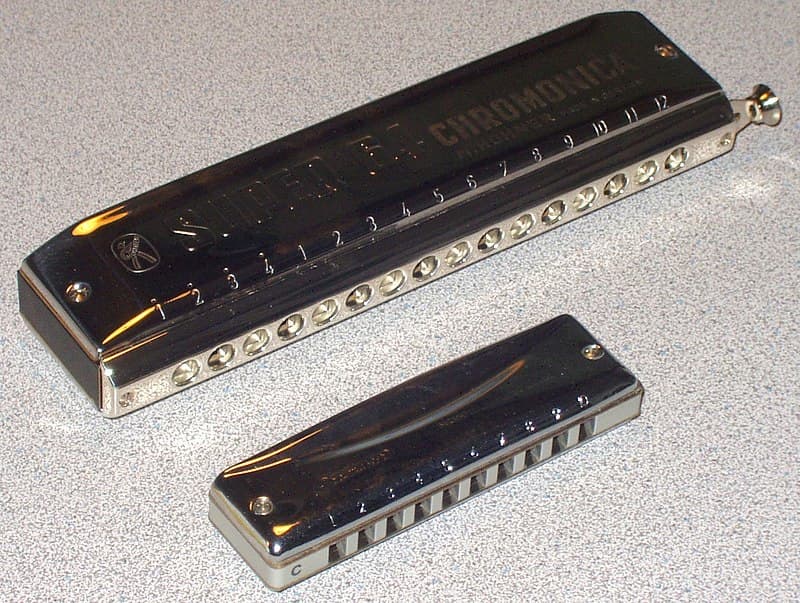

The harmonica, also known as the mouth organ, is a free-reed wind instrument developed in Europe in the early part of the 19th century. Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann is often cited as the inventor of the harmonica in 1821, and the first harmonicas produced by clockmakers appeared in Vienna shortly thereafter. Joseph Richter invented the blow and draw mechanism that allows players to activate twenty differently tuned reeds by inhaling and exhaling. These diatonic harmonicas were primarily designed to play folk music, and by mid-century, the instrument was being mass-produced. The invention of the chromatic harmonica by Hohner in 1924 created new possibilities for the instrument, and it appeared in a variety of musical styles, including American folk music, blues, jazz, country, and rock. Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) composed a substantial number of concertos for famous performers. This was certainly the case with the famous harmonica player John Sebastian, who enjoyed a long career as a soloist that started in Philadelphia in the early 1940s. Sebastian commissioned a harmonica concerto from Villa-Lobos in 1955, and he premiered the work in Jerusalem with the Kol Israel Orchestra in 1959. The concerto is packed with technical challenges for the soloist, including octaves and chords, but Villa-Lobos also highlights the powerfully expressive qualities of the instruments. Villa-Lobos and Sebastian are essentially responsible for introducing the harmonica into the concert hall.

Harmonica

Emma Lou Diemer: Concerto in One Movement for Marimba

Emma Lou Diemer

The marimba is a percussion instrument that features a set of wooden bars arranged like the keys of a piano. Resonators are typically suspended underneath the bars to amplify the sound produced by striking the bars with yarn or rubber mallets. The ancestry of the instrument can be traced to Sub-Saharan Africa, and it rapidly spread to Central and South America. Today, marimbas are widely popular around the world and Darius Milhaud introduced the instrument into Western classical music with a Concerto for Marimba and Vibraphone in 1947. Ever since, composers like Leoš Janáček, Carl Orff, Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Hans Werner Henze, Pierre Boulez, and Steve Reich have found new and exciting ways of using the marimba. That also includes the Concerto in One Movement for Marimba by American composer Emma Lou Diemer. A native of Kansas City, Diemer is a keyboard performer, and she has engaged with an eclectic style of composition. She has composed traditional, experimental, and electronic works using tonal and atonal musical languages. Commissioned by the Women’s Philharmonic of San Francisco, the Marimba Concerto premiered on 21 March 1991 at Mills College with JoAnn Falletta conducting and Deborah Schwartz as the featured soloist. A reviewer wrote, “This was a premiere worth waiting for… A stirring score that explores the colors of the marimba in glorious detail… The composer and soloist have taken an inert instrument of wooden bars and metal tubes and given it a human throat with which to sing. Marimbists around the world have cause to celebrate.”

Marimba

Andy Akiho: Ricochet “Ping Pong Concerto”

Ping Pong Concerto

Andy Akiho is a composer of contemporary classical music. He is a virtuoso percussionist based in New York City, and his primary performance instrument is steel pans. In fact, he took several trips to Trinidad after graduating from college in order to learn and play music. His compositional interest was peeked by participating in the “Bang on a Can” Festivals in 2007 and 2008. Akiho developed a reputation for writing music that makes use of metallic sounds and incorporates elements of theatre. Concertos are generally written to highlight a virtuoso soloist or two, but there are no specifications as to what kind of instruments are to be used. Theoretically, they can be written for anything that produces sound.

Andy Akiho

Such is the case in Akiho’s Ricochet, a triple concerto for violin, percussion, and ping-pong players. Working in his preferred instrumental medium, Akiho incorporates a ping-pong tournament into his concerto score. The violinist opens the piece with a solo and is soon joined by a percussionist who turns the ping-pong table into an instrument. But we quickly realize that a game of ping-pong is the major component. Commissioned by the Beijing Music Festival in 2015, the ping-pong soloists at the premier performance are both accomplished athletes. Michael Landers and Ariel Hsing are the youngest U.S. Women’s and Men’s table tennis champions, and Hsing competed in the 2012 London Olympics. A reviewer wrote, “So riveting was this piece as a visual theatre that no one seemed to keep score.”

Wednesday, April 24, 2024

20 Beautiful Female Classical Violinists

Ein Walzertraum - Oscar Straus (1870 - 1954)

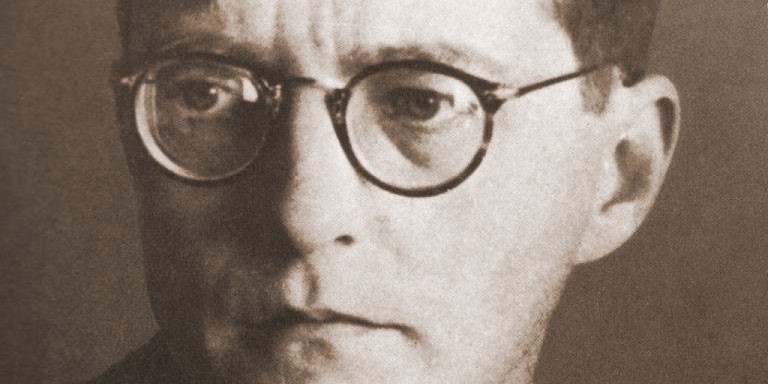

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Following his death, the government of the USSR issued the following summary of Shostakovich’s work, drawing attention to a ‘remarkable example of fidelity to the traditions of musical classicism, and above all, to the Russian traditions, finding his inspiration in the reality of Soviet life, reasserting and developing in his creative innovations the art of socialist realism and, in so doing, contributing to universal progressive musical culture’. The Times wrote of him in its obituary that he was beyond doubt ‘the last great symphonist’.