Music salons of Belle Époque Paris

The piano was the most important musical instrument in the home “because it was useful as both a solo instrument and as accompaniment to a group of singers or instrumentalists.” In essence, the piano was the axis of cultural, communal, and family life. The grand piano became a powerful symbol of the aristocratic salon, but to accommodate home use, smaller pianos were created. Square pianos and uprights took up less space and they were less expensive. “With the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, the mass manufacturing of musical instruments, especially pianos provided a seemingly endless supply for huge markets.

Les Femmes “Compositeurs” eagerly contributed a delightful piano repertoire of richness and complexity, one that is nevertheless, not exclusively tied to the salon. In this blog let us sample piano music by French Romantic Women Composers, starting with 5 Pieces by Mélanie Bonis.

Mélanie Bonis: Cinq pièces pour piano, Op. 11

Mélanie Bonis, 1907

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) and Claude Debussy were fellow students at the Paris Conservatoire. Interestingly, Bonis was rather critical of his impressionistic compositions. As she writes, “In music, harmony corresponds to colour in painting, to building materials in architecture. Debussy uses the most precious materials, brilliant and opaque jewels, but his constructions have neither plan nor scale. He is a delightful illustrator of short little things.” Bonis, on the other hand, felt strongly drawn to traditional forms, but unlike Debussy, she was denied veritable success during her lifetime. She had been forced to discontinue her studies, and prevented from marrying the man she loved. Her parents pushed Bonis into a marriage with Albert Domange, 22 years her senior who brought five children into the marriage. They stayed together for 35 years, but Bonis never gave up composing and left us a substantial collection of piano music. The “Cinq pièces pour piano” are charmingly light and elegant, and you can easily hear the influence of Schubert in the opening impromptu, Mendelssohn in the song without words, and Schumann in the concluding “Papillons.”

Virginie Morel du Verger: 8 Études mélodiques

Virginie Morel (1799-1869) is not a household name, and I must confess that I had never heard of her before the Palazetto Bru Zane published its anthology of French Romantic Women Composers. There is very little biographical information available, but she was apparently born in Metz and taught herself to play the piano. By the age of 12 she “played the piano remarkably well,” and after she entered the Paris Conservatoire in July 1813, she quickly gained attention. The composer Méhul noted, “She has the greatest potential to become a leading pianist.” True to his words, Morel won the Premier Prix in piano the following year and completed her education by taking private lessons with Reicha (in harmony), Clementi, and Hummel. Her first compositions are dedicated to the Duchesse du Berry, and her arranged marriage to the chief of staff in the Armée d’Afrique took her away from musical life in Paris. In fact, she spent ten years in Algiers before returning to France.

Upon her return, Morel continued to teach and compose, writing music for her own instrument. And that includes the collection of Huit Études mélodiques published in 1857 and dedicated to Louise Farrenc. The title “Études” is somewhat misleading as these are not pedagogical words. As the liner notes tell us, “Despite being fraught with various difficulties, these eight short pieces are intended for a salon performance, and as a demonstration of the expressive talent of both the performer and the composer.” As Ernest Reyer wrote on 31 July 1857 in the Revue musicale, “The artistic world still remembers Miss Morel’s successes; and as the skillful pianist became a noble lady, she remained faithful to her art and to the only traditions she ever accepted, those of the great masters. Each page of the work gives a feeling of virility and experience: feminine grace is hidden in the titles the composer gave to each of the melodies that form her collection: ‘La berceuse’ (‘Lullaby’), ‘L’incertezza’ (‘Uncertainty’), ‘Barcarolle’, ‘Le papillon’ (‘The butterfly’), etc. These fresh poetical thoughts are preceded by a very beautiful introduction in which both parts, equally interesting and eventful, reveal the masterly touch of a hand that never fumbles.”

Marie Jaëll: Voix du printemps

Marie Jaëll

With the piano taking center stage in the salons and living rooms of the 19th century, music became a widely accepted form of home entertainment. As my colleague once wrote, “and when two people sit at one instrument sharing space and often the same notes, the interactive side of music making is elevated to a physical level.” Performance by two players simultaneously sharing a single piano requires not only a level of intimacy unique to chamber music, it also presents its own set of technical challenges. There are some notable exceptions, but the piano four hands repertoire is primarily associated with domestic music making. Marie Jaëll (1846-1925) composed a collection of music for four hands in 1885 and titled it Voix du printemps. She premiered the work with pianist Lucie Wassermann in February 1886 at the Salle Érard. A critic considered these works “full of verve, and of the best style.” Les Voix du Printemps “sing in a pleasant rural setting, and if the storm disturbs the tranquility, it is to bring a necessary dramatic contrast.”

Mélanie Bonis: 6 Pièces à quatre mains, Op. 130

Composer Mel Bonis (on the Left in the lounge chair) enjoying a picnic with friends

In her

Six Pièces à quatre mains pour piano composed in 1930, Mel Bonis turned to expressions of religious inspiration and to compositions for the musical education of children, especially her own grandchildren. This delightful set published as her Opus 130 is simultaneously designed for a beginning and advanced pianist sharing the keyboard. For each piece, Bonis “indicates the parts for “l’élève” which, as the title states, are very easy, and those for “le maître,” which are much more elaborate.” And as you can hear this as each piece offers a different level of technical difficulty. “This approach,” as a scholar wrote, “ensures that the beginner is not confined to works that are too basic and is able to hear the subtleties offered by the instrument while participating.” In some pieces, which alternate an exotic with a religious mood, the student plays the lower part of the piano or the higher part, “and is given a single formula, which is repeated ostinato throughout the piece.”

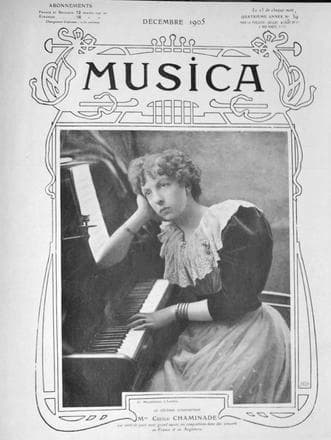

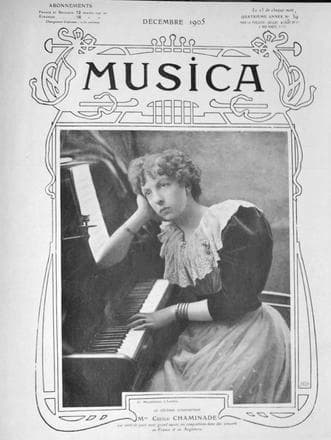

Cécile Chaminade: 6 Pièces romantiques, Op. 55

Cécile Chaminade

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) was born into an upper-middle-class family and her father was against his daughter having a professional musical education. The family did hold regular salons at their house and Cécile made the acquaintance of various musicians who helped her to arrange for her first public performance at the Salle Pleyel in 1877. A critic writes, “the death of her father and the need to provide for her family prompted her, from the 1890s, to give frequent international concert tours and sign publishing contracts which obliged her to produce at speed a large number of minor works which generally lack the harmonic sophistication of her early compositions.” Personally, I don’t hear that lack of harmonic sophistication in her Six Pièces romantiques op. 55 composed around 1890. The poetic qualities of this set are described in the titles of individual pieces and orient themselves by two very popular subjects of the time, nature and exoticism. Just listen to the pastoral freshness and elegant lines and harmonies in “Primavera,” and the modal touches and arpeggiated chords of some plucked string instruments as it evokes a distant land in “Idylle arabe.”

Charlotte Sohy: Piano Sonata, Op. 6

Portrait of Charlotte Sohy

Piano compositions by Les Femmes “Compositeurs” were clearly not exclusively bound to gentle afternoon performances at the salon. In the case of Charlotte Sohy (1887-1955), her Piano Sonata Opus 6 first sounded at a concert given by the Société Nationale de musique on 9 April 1910. Sohy had been a student of Vincent d’Indy and the Schola Cantorum, and a younger generation of avant-garde composers led by Maurice Ravel eyed her with great suspicion. Nevertheless, a critic present at the performance wrote, “The piano sonata by M[onsieur] Ch. Sohy has the great merit of being short and to the point; the author knows what he wants to say and how to say it and has no intention of saying too much. He is to be encouraged in that approach, and it cannot be denied that the first two movements offer some personal qualities as well as some delightful sounds, and the third one, in the form of a rondo based on a Russian dance theme, moves fervently and with ease through many varied tonalities.” As you can tell, Charlotte concealed her gender by signing the work as “Ch. Sohy,” which the critic automatically assumed was a man.

Hélène-Antoinette-Marie de Nervo de Montgeroult: Piano Sonata in F minor, Op. 5 No. 2

Hélène-Antoinette-Marie de Nervo de Montgeroult

The F-minor piano sonata by Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836) was first published in 1811. Born Hélène de Nervo in Lyon, she was “often regarded as the greatest virtuoso of her time, which could have guaranteed her a prestigious career, had her aristocratic background not forced her to remain within the narrow confines of the Paris salons.” She was a student of Dussek and Clementi, and the first woman appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire in 1795. As such, “she actively helped to train the first virtuosos of the 19th century, including Cramer and Boëly. And it seems that music also saved her life. During the Reign of Terror in Revolutionary France, she was imprisoned and had to appear before the Committee of Public Safety. Faced with being marched to the guillotine, de Montgeroult was asked to prove that she might be useful for patriotic events. A piano was brought in and she was asked to perform “La Marseillaise.” After playing the tune, so the story goes, “she began to improvise a set of variations with the music gradually building to a great climax, the melody billowing out over arpeggios.” Having moved everybody to tears, Hélène de Montgeroult was quickly released.

Her biographer Jérôme Dorival considers de Montgeroult a bridge between classicism and romanticism. He described her as “the missing link between Mozart and Chopin.” The featured piano sonata shows an “unexpectedly early influence on French composers of the Germanic piano repertoire, and in particular the works of Beethoven.” It is a highly dramatic composition in which the musical material is highly unified. “The first theme of the Allegro thus proceeds by successive amplifications and transformations, while the second theme is of a more songful character. The second movement features two highly expressive themes, and the work ends with a spirited fast movement full of tonal contrast, setting this sonata firmly in the vein of early Romanticism.”

Mélanie Bonis: Suite en forme de valses, Opp. 35-38, No. 1

Let us conclude this little survey of piano music by French Romantic Women Composers with the delightful Suite en forme de valses by Mel Bonis. This suite exists in several versions, all composed in 1898. There is a version for orchestra and solo piano and one for piano four hands in five movements. The version of piano four hands is not a transcription of the orchestral version. As the liner notes tell us, “technically accessible to amateur pianists, the Suite en forme de valses was intended for domestic use, but the composer also displays new ambitions in confronting here the orchestra for the first time.” Please join us next time for a concluding survey of delightful French mélodies composed by Les Femmes “Compositeurs.”