© weinberger.co.at

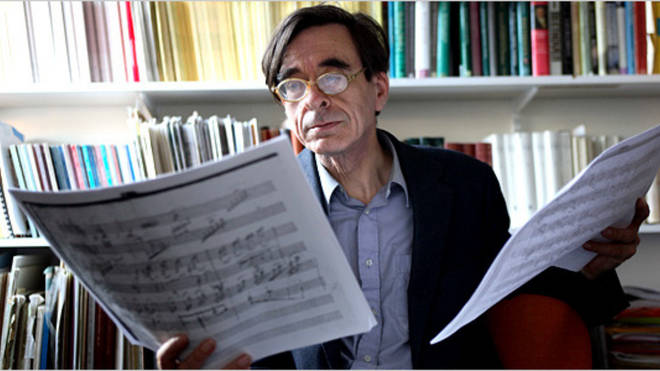

The genius pianist Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) was lauded for his extraordinary interpretations of the music of Bach, Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven. Highly sought after as a piano teacher, his students included Martha Argerich and Claudio Abbado. However, Gulda openly flaunted classical music etiquettes and conventions, playing some recitals in the nude. And in what some people have described as a tasteless publicity stunt, he even faked his own death in 1999. The entire classical music world lined up to pay tribute to Gulda, when a Geneva concert agent contacted the news media and reported seeing the pianist “remarkably alive.” Seemingly, Gulda sent a fax from Zurich airport announcing his own death in order to see what kind of obituaries would be written about him. “People have thrown so much muck at me while I am alive, I do not want them to chuck it into my grave as well.” All protestations aside, it might be telling that Gulda’s very next concert titled “Resurrection Party,” was fully booked.

Friedrich Gulda: Cello Concerto (Ernst Simon Glaser, cello; Royal Norwegian Navy Band; Peter Szilvay, cond.)

Gulda had a strong dislike for authority, and he refused to accept the “Beethoven Ring” offered by the Vienna Academy in recognition of his performances and recordings. He often made last-minute program changes onstage, and freely cultivated an interest in jazz. For Gulda, pianists who didn’t also compose were not to be considered real musicians. In his compositions, stylistic references to jazz gave way to improvisations and arrangements of the popular-music repertory. Teaming up with the likes of jazz great Chick Corea, Gulda uncompromisingly expressed his anti-bourgeois artistic convictions by jarringly juxtaposing elements and styles borrowed from jazz, folksong, electronic music and the classical music repertoire. It is hardly surprising that in classical circles he earned the nickname “terrorist pianist,” a moniker Gulda was predictably rather proud of.

Gulda is commonly regarded as the “cross-over” pioneer of his time, and his most frequently performed work is the Concerto for Cello and Wind ensemble.

Composed for the cellist Heinrich Schiff in 1980, the work premiered at the Vienna Konzerthaus on 9 October 1981 with Schiff as the soloist and Gulda conducting. According to Gulda, Schiff only commissioned and performed this work because he wanted to make a recording of the Beethoven cello sonatas with Gulda. However, the cello concerto became such a rousing success that Schiff eventually forgot about Beethoven. The work bears a surprising double dedication—to Schiff and to the controversial socialist chancellor Bruno Kreisky, who held office at that time.

Composed for the cellist Heinrich Schiff in 1980, the work premiered at the Vienna Konzerthaus on 9 October 1981 with Schiff as the soloist and Gulda conducting. According to Gulda, Schiff only commissioned and performed this work because he wanted to make a recording of the Beethoven cello sonatas with Gulda. However, the cello concerto became such a rousing success that Schiff eventually forgot about Beethoven. The work bears a surprising double dedication—to Schiff and to the controversial socialist chancellor Bruno Kreisky, who held office at that time.

A conventional and classically inspired cello gesture immediately leads into a swinging Big Band riff, including percussive back beats and improvisatory cello passages. The contrasting theme in this “Overture,” on the other hand, comes straight from the Austrian mountainside. This “Ländler” features lilting dance rhythms in the woodwinds with obligatory Alpine horn calls, and eventually both sections are repeated. The “Idyll” returns us to the Austrian Alps. Indigenous and melodious folk tunes are first sounded in the brass chorus and subsequently taken by the soloist. The “Cadenza” skillfully embeds a variety of musical styles within a virtuoso character, while the “Menuett” opens with a cello cantilena accompanied by the guitar. Subsequently, the flute in conversation with the cello gracefully presents the musical contrast. Critics have spitefully suggested that Gulda’s music conveys an ironic distance to his native folk music. These sentiments, however, are not confirmed in the “Finale,” as a stylized marching band splendidly communicates with a classically inspired soloist.