Franz Schubert

Throughout the 19th century, piano music for four hands played an important role in the home. Since larger ensembles could only be afforded by the upper classes and the aristocracy, salons everywhere sounded with music for four hands, be it arrangements of works written for larger ensembles, the operatic stage, or original compositions.

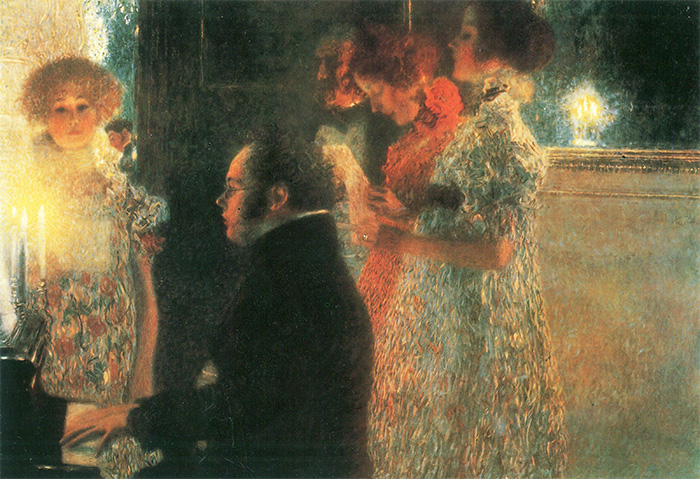

For Schubert, the four-hand set-up seemed ideally suited to his temperament as “it was a congenial form of music-making that was emblematic in Biedermeier culture as an activity of friendship and sociability.” These works were a staple in Schubertiade’s gatherings, and they ranked among his most successful publications during his lifetime. As we commemorate Schubert’s passing on 19 November at the age of 31, let us celebrate his genius by exploring some of his genial and charming original works for piano 4-hands.

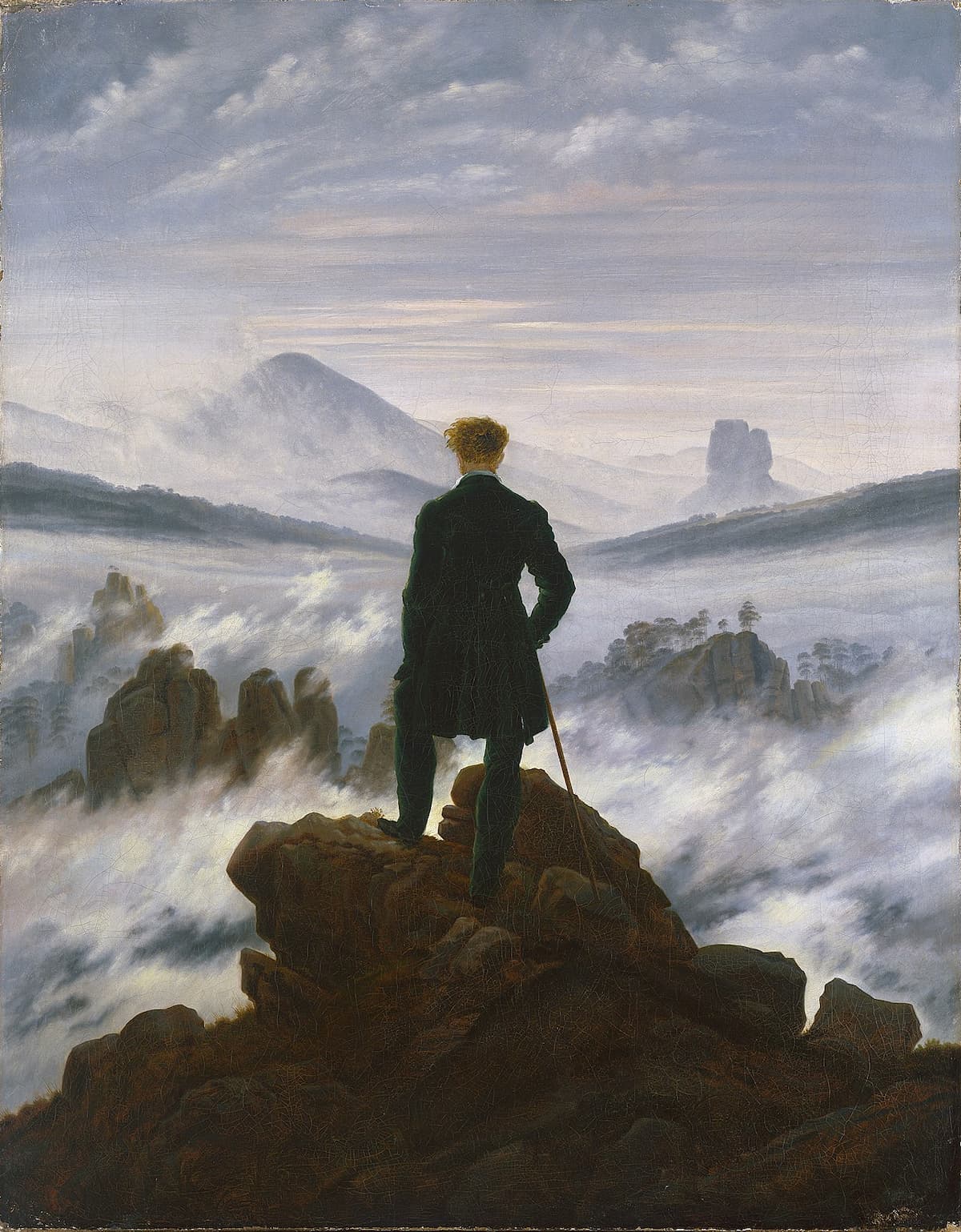

Franz Schubert wrote to a friend, “Every night when I go to bed, I hope that I may never wake again, and every morning renews my grief.” Yet, it was music that gave him purpose. As he wrote, “I compose every morning, and when one piece is done, I begin another.” In May and June 1828, Schubert composed the Allegro in A Minor, D 947 and the Rondo in A Major, D 951, as a possible two-movement sonata.

The Rondo was published in December 1828, a month after his death, but the Allegro only appeared in print in 1840. Anton Diabelli added the heading “Lebensstürme” (The storms of life), presumably with an eye on prospective customers. This trite sobriquet does not prepare us for the depth of Schubert’s music, as harmonic and structural shifts create subtleties of light and shade. Schubert was the undisputed master of compressing emotional complexity, joy, sorrow, friendship, and solace into a simple change of key.

Turbulent minor chords prepare for an opening statement that emerges from within a deep silence. An introspective melody murmurs in the unsmiling minor key, but the serenity of the second theme, sounding a distant chorale, leaves all storms far behind. However, Schubert has led the music into a highly remote territory, with the harmonic ground shifting restlessly. Suddenly, the music breaks off mid-stream, and an unceremonious plunge takes us to the central development stage. And while the radiant chorale takes centre stage in the recapitulation, the movement ends in the stormy minor key.

With the “Lebensstürme” Allegro and the “Grand Rondeau,” Schubert completely transcended the confines of the salon and, in the process, wrote highly original and wonderful music for piano duet. The Schubert biographer Christopher H. Gibbs writes, “Such innovations may explain why his attraction to the medium continued even after his energies shifted increasingly to large-scale instrumental works. Indeed, the audacious harmonic and structural adventures in his finest keyboard duets may have pointed the way to orchestral projects that he did not live to realise…The late piano duets exquisitely merge Schubert’s lyrical gifts with daring formal structures.”

Franz Liszt called Schubert “the most poetic musician who had ever lived,” and musicologist Alfred Einstein called the A-Major Rondo D. 951 “the apotheosis of all Schubert compositions for four hands.” The piece is modelled on the lyrical second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in E minor, Op. 90. It mirrors the tranquillity of mood, the layout, and the harmonic pattern.

The Rondo theme is quietly accompanied by running 16th notes and immediately sounds an octave higher. This theme appears in various keys and registers throughout, and it is interspersed with episodes and subsidiary themes derived from it. A slightly stormy section in C Major is quickly cast aside, and the Rondo theme returns in the cello register to conclude the movement in a warm and quiet manner.

Variations in B-flat Major, D. 968a

Caroline Esterhazy

For Schubert and his friends, four-hand piano music was a natural part of convivial evenings. This repertoire was almost exclusively destined for the private amateur salon market, and the prospects for having such pieces published were higher than they were for solo piano music, specifically when it came to works of the ambitious scope Schubert wanted to write.

Presumably written in 1818 or 1824, Schubert’s Variations D. 968a for piano four hands is one of series of compositions written for the two daughters of Count Johann Karl Esterházy. Schubert was engaged as a music tutor to the two girls and spent two summers at the Count’s estate at Zseliz in Hungary. Schubert wrote to his friend Moritz von Schwind, “I have composed a big sonata and variations for four hands; the latter is enjoying great applause here, but since I don’t quite trust the taste of the Hungarians, I’ll let you and the Viennese decide about them.”

A curiously pompous introduction terminates in a short cadenza for the primo pianist, and it is followed by a simple theme of Schubertian charm. The variations get progressively more brilliant, with Schubert accelerating the rhythms and adding rapid figuration. The third variation is aptly marked “Brilliante,” and it is followed by the mock solemnity of a slower variation. The merry finale features folk-like elements, including a yodelling call. It has been called “one of Schubert’s most jovial and overtly entertaining pieces.”

Sonata for Piano 4-hands in C Major, D. 812 “Grand Duo”

The big sonata Schubert mentioned to Moritz von Schwind turned out to be one of the most monumental and powerful achievements of the composer. Generally known as the “Grand Duo,” the work caused a bit of confusion. As Robert Schumann wrote in 1838, “I thought at first it was a symphony transcribed for piano, but the original manuscript on which Schubert has written Sonata for four hands would suggest I was wrong.”

Schumann continues, “I say I would suggest, for I am still not convinced of my error. A composer as prolific as Schubert may well, in haste, have written Sonata when what he really had in mind was a symphony. Knowing his style and his manner of writing for the piano and comparing this work with his other sonatas where the purest pianistic character is evident, I cannot but think that it was composed for the orchestra. You can hear the strings, the woodwind, the tutti, some solos, the drum roll; the symphonic form in all its breadth and depth.”

Joachim’s orchestration of Schubert’s Grand Duo

Joseph Joachim went ahead and orchestrated the “Grand Duo” in 1855, and the musicologist and composer Donald Francis Tovey included this orchestration in his book analysing symphonies. He wrote, “there is not a trace of piano style in the work.” More recently, the Sonata has been more readily appreciated as a piano work with orchestral effects, one of many other piano works by Schubert that have been called “symphonies in disguise.”

Actually, Schubert wrote two sonatas for piano 4-hands. While the “Grand Duo” dates from 1824, the “Grande Sonata” originated in 1818. The two works couldn’t be more different, as the “Grande Sonata” seems very close to the world of Mozart, “the unique combination of purity, subtlety and emotional richness of whose music was an abiding source of wonder to Schubert.”

A grand opening gesture, a wonderful curtain-raiser, proceeds to an easy-going theme. The contrasting second subject sounds in a remote key, but it cheekily meanders back to the correct key just in time to close the exposition. Schubert also introduces a charming new melody in the middle of the development, which will be echoed in the beautiful slow movement. The Rondo finale takes a renewed look at Mozart with a dramatic, almost operatic middle section and replaces the development.

The work stems from Schubert’s time at the Esterházy’s estate at Zseliz in Hungary, and it found the composer in a jovial mood. He writes, “I am in the best of health. I live and compose like a god, as though indeed nothing else in the world were possible… I am really alive at last, thank God!”

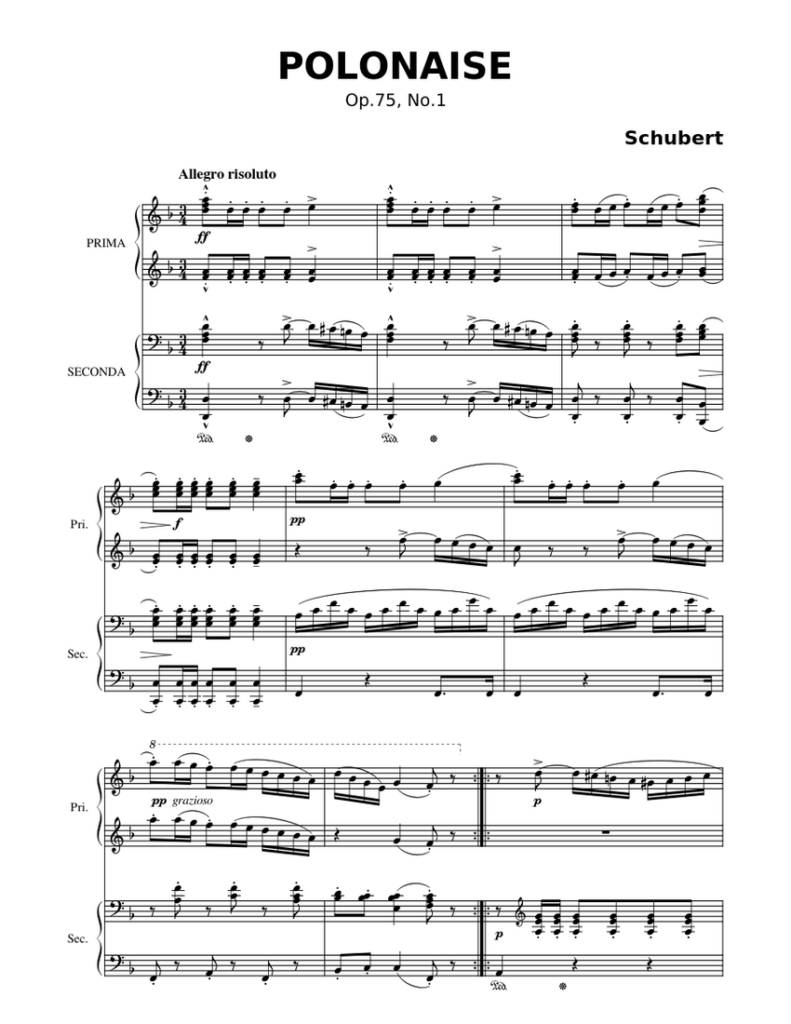

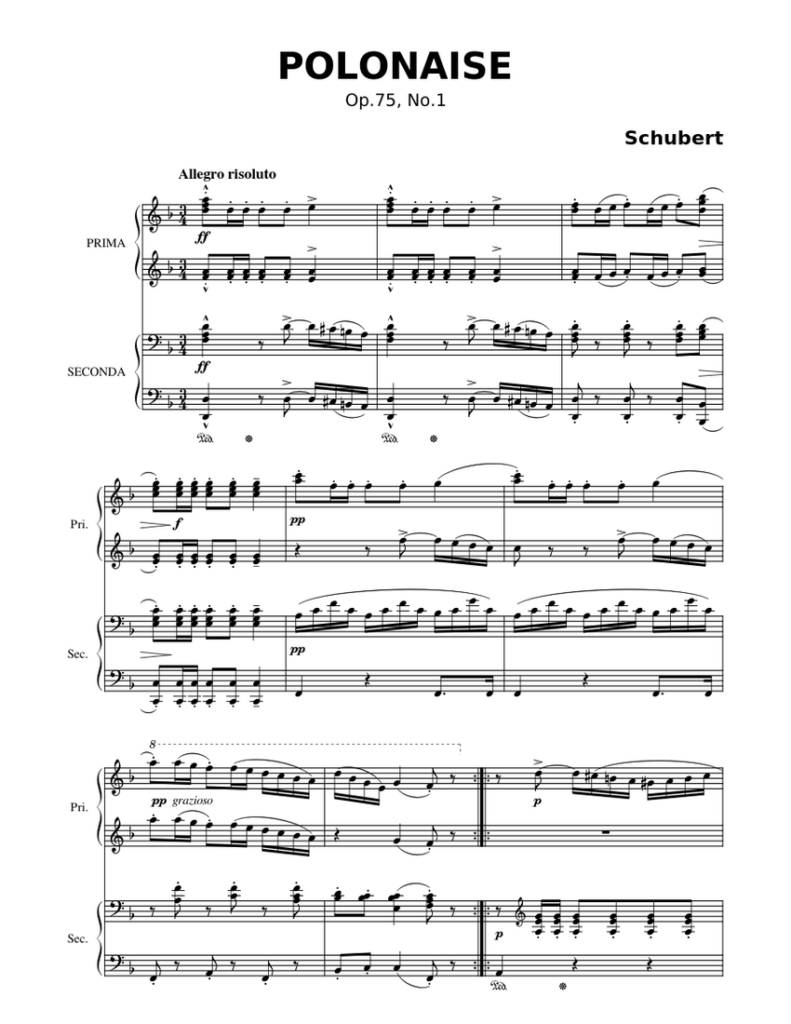

Polonaises, D. 599

Schubert’s Polonaise

Schubert published a couple of sets of Polonaises in 1826 and 1827. The young Robert Schumann, not yet seventeen, was already reviewing for a Frankfurt publication and wrote of “most original and very richly melodious little movements… The execution is difficult at times on account of the sometimes surprising and sometimes far-fetched modulations. Thoroughly recommended.”

Schumann called them “romantic rainbows over a sublimely slumbering universe,” as Schubert turned the Polish courtly ceremonial style of music into his own delightful and sparkling character pieces. The Polonaises for piano 4-hands range from light and airy to robust and balletic, but all unfold in three-part form and venture into unexpected keys.

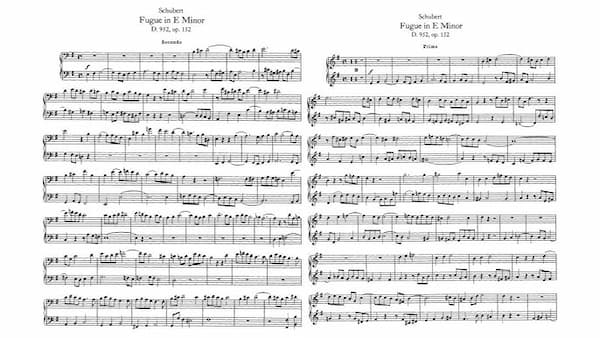

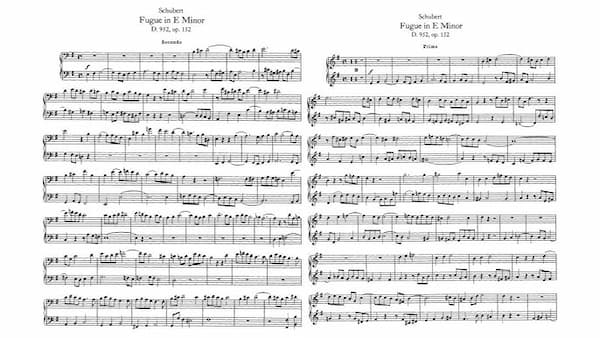

Fugue in E minor of Piano 4-hands, D. 952

Schubert’s Fugue in E minor

In 1828, Schubert and his friend Franz Lachner were invited by Johann Schikh, the editor of a Viennese magazine for art, literature, theatre, and fashion, for a country outing to Baden, near Vienna. Apparently, Schikh told Schubert, “Tomorrow morning, we shall go to Heiligenkreuz to hear the famous organ there. Perhaps you could both compose a small piece and perform it there?” Schubert suggested the composition of a four-hand fugue, which was completed by midnight.As Lachner reports, “on the next day, at 6 in the morning, we travelled to Heiligenkreuz where the fugues were performed in the presence of several monks.” The fugue subject had already appeared in Schubert’s counterpoint lesson with Simon Sechter, and it might well have been his very last completed composition. As he wrote to a friend eight days later, “I am ill. I have had nothing to eat or drink for eleven days now and can only wander feebly and uncertainly between armchair and bed.”

Fantasie in F minor, D 940

Schubert composed a number of Fantasies, but the one in F minor, D 940, is surely one of the best-loved works in the piano duet literature. But what is more, it is widely considered one of Schubert’s greatest masterpieces. Dedicated to Countess Caroline Esterházy, this work completely leaves the sphere of informal social gatherings. During the first months of his last year of life, Schubert created a work of almost symphonic form, whose elegiac atmosphere at the beginning sets the tone for the entire work. Schubert scholar John Reed called it “a work which in its structural organisation, economy of form, and emotional depth represents Schubert’s art at its peak.”

Although Schubert called it a Fantasie and the work unfolds in one continuous flow of music, it might well be structured in the manner of a sonata in four movements. The opening “Allegretto molto moderato” evolves from a murmuring accompaniment that features a theme of halting rhythms and chirping grace notes. When Schubert almost hypnotically repeats the theme, the music has effortlessly shifted from F minor to F Major. The rhythmically conceived second subject drives directly into a powerful “Largo.” We move directly into the “Allegro vivace,” a sparkling scherzo of nostalgia followed by a delicate trio. The trio breaks suddenly, and the music eventually plunges into a complex fugue, which takes us to the point of despair. The concluding section brings back the music from the very beginning, and contrapuntal complexity drives the Fantasie to its climax. It all ends with some heart-rendering chords that bring this masterwork to a quiet close.

A scholar writes, “that a legacy of such beauty should have been bequeathed to all humanity as a result of Schubert’s pain and suffering is a miracle in itself.” And Schubert himself commented in the final moments of his life, “the product of my genius and my misery, and that which I have written in my greatest distress, is that which the world seems to like best.”

Franz Schubert died in Vienna on November 19, 1828, and he was buried at his own request near Beethoven. Schubert had carried the torch at Beethoven’s funeral a year before his own death.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.