by Georg Predota , Interlude

Robert Schumann

For the 7th birthday of his daughter Marie, Robert Schumann compiled a short album of “Little Piano Pieces.” Once he had gotten that process started, Schumann kept adding miniatures to the collection. His wife Clara Schumann wrote in her diary, “The pieces usually given to children at their piano lessons are so bad, that it has occurred to Robert to bring out a collection of such little works himself.” Schumann was on fire and reported to his friend Carl Reinecke, “I cannot remember ever feeling as content as when working on these pieces… I felt as though I were starting to compose all over again!” Schumann composed the 43 pieces of his Album for the Young in barely 2 weeks, but a good many more miniatures have surfaced in various manuscripts but were not included in the published collection. The set is subdivided into two parts, starting with pieces “suitable for younger players,” and concluding with pieces “appropriate for more mature players.” Clara Schumann prepared the final edition and tellingly wrote, “Never play bad compositions, nor even listen to them, unless absolutely obliged to do so.”

The Evening Star

You lovely star,

You shine from afar,

And so I hold you

Dearly in my heart.

How I do love you

So deep in my heart!

Your twinkling eyes

Look ever on me.

So I look to on you,

As you are there or here:

Your friendly eyes

Stand ever before me.

How you nod at me

In peaceful rest!

O lovely little star,

O were I like you!

(Translation © Gary Bachlund)

Robert Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young

Six months later, Clara Schumann was expecting her fifth child, and Robert Schumann followed up his Album for young pianists with one for young singers. The inspiration for his Album of Songs for the Young might well have been pedagogical, as he considered singing a fundamental part of music education. As he recommended in his pamphlet Musical House and Life Rules, “Try, if you also have only a little voice, to sing from the page without the help of the instrument … But if you have a resonant voice, do not hesitate a moment in cultivating it, consider it as the finest gift that heaven bestows on you! He who wants to cultivate a complete musical personality should not only strive for instrumental virtuosity, as on the piano, but should not neglect singing.” In no time, Schumann had composed 25 solos songs and 4 duets, and he wrote to his publishers: “This collection will best express what I had in mind. I have selected poems appropriate to childhood, exclusively from the best poets, and have tried to arrange them in order of difficulty, progressing from the easy and simple to the difficult and complex. At the end comes Mignon, gazing into a more troubled emotional life.”

Butterfly

[Oh] butterfly tell,

Why do you flee me?

Why are you in such haste,

Now far and then near?

Now far and then near,

Now here and then there–

I shall not catch you,

I shall not harm you.

I shall not harm you:

O stay here always!

And I were a little flower,

I would say to you,

I would say to you:

Come, come to me!

I give you my little heart,

How fond I am of you!

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

Clara and Robert Schumann

Scholars have suggested “for all their apparent simplicity, these songs need to be performed with loving detachment rather than wallowing sentimentality, and the singers who have been most successful with this repertoire are those who have not turned themselves into children.” The Album of Songs for the Young is not simply a loose collection of songs, but it should be considered a genuine cycle. Fundamentally, “it reflects Schumann’s understanding of the formal and substantial development of folksong into something more elaborate, and it also discloses an exemplary exegesis of a phenomenon by way of varied possibilities for interpreting a given poem in a musical setting.” Following the pattern established in his Album for the Young, Schumann divides the song collection into two sections “For the Younger,” and “For the Older.” The first section begins in the world of children and deals with animals, nature, and daily life. We also find songs of the gypsy lads and shepherd boys, as well as the sandman and the ladybird. The second section leads us into a world of wider experiences and feelings, from the pantheism of Goethe’s “Song of Lynceus the Watchman” to the yearning of “Mignon.”

The Sandman

I wear a fine pair of boots

with wondrously soft soles,

I carry a sack upon my back!

Hush, I scamper quickly up the stairs.

And when I enter the chamber

The children are saying their prayers:

Two little grains of my sand

I scatter into their eyes,

Then they sleep the whole night

Watched over by God and the angels.

Two little grains of my sand

I scattered into their eyes:

The good little children should be visited

By a beautiful dream.

Now rapidly and swiftly with my sack and my stick

back down the stairs!

I can no longer stand around idly,

I must still visit many [children] tonight.

You are already nodding off and laughing in your dreams,

And I barely opened my little sack.

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

Robert Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young, 29 May, 1849

In terms of music, Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young offers increasing levels of difficulties. In the opening “children’s songs” the melody is primarily supported by simple but delightful harmonic progressions in the piano. The harmonic accompaniment, sophisticated as it well may be, is simply intended to support a young singer. It has been suggested that Schumann here “follows the tradition of pedagogically oriented collections of songs for children from the 18th century, found in a variety of published sources.” These songs can also be performed together in the family circle. Mailied (May Song) has a second voice ad lib, some numbers are for two voices, while Spinnelied (Spinning Song) is for three, and in Weihnachtlied (Christmas Song), with the text attributed to Hans Christian Andersen, at the end a chorus can join in with the refrain ‘Hallelujah, Kind Jesus’ (Alleluia, Child Jesus).”

Christmas Song

When the Christchild was brought to the world,

Who has rescued us from hell,

He lay in a manger in dark night,

Pillowed on straw and hay;

But above the hut there shone the star,

And the ox kissed the foot of the Lord.

Halleluja, Child Jesus!

Take courage, soul that is sick and weary,

Forget your gnawing pains.

A child was born in the city of David

As a comfort for all hearts.

Oh let us go to the little child,

And become children in mind and spirit.

Halleluja, Child Jesus!

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

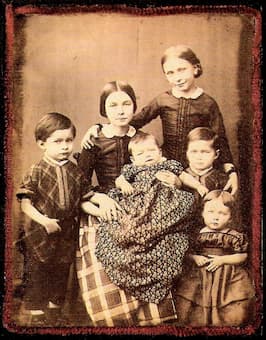

Clara and Robert Schumann’s children

Scholars have suggested that the songs of Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young hold only a marginal position in musical life today. “For young singers they seem in part overtaxing, but because of their pedagogic aims, on the other hand, they are artistically undervalued by adult singers. The first numbers in particular seem too childish for performance by a concert singer. It may be argued, however, that Schumann’s songs conjure up, not naively but in feeling, the innocent world of childhood.” Aesthetically, they seem close to his piano set “Scenes of Childhood,” which also present idyllic reflections of childhood by adults. That sense of childhood idyll is clearly seen on the title-page of the first edition, which portrays a group of children singing and making music in a paradise of a natural setting “of leafy tendrils with flowers, fruits and nesting birds.”

Watching over children

When good children go to sleep,

Two little angels stand by their beds,

They tuck them in and tuck them up,

And keep a loving eye on them.

But when the children get up,

Both the angels go to sleep,

If the angels’ strength is now not enough,

The good Lord himself keeps watch.

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young develops from children’s songs to pure art song in the Mörike setting “Er ist’s” (It is Spring).

Spring is here

Spring is floating its blue banner

On the breezes again;

Sweet, well-remembered scents

Drift portentously across the land.

Violets, already dreaming,

Will soon begin to bloom.

Listen, the sound of a harp!

Spring, that must be you!

It’s you I’ve heard!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

The piano and vocal part are quietly restrained in the first half of the song, possibly suggesting that spring can already be sensed, but that it has not yet arrived. However, after a delicate and light staccato arpeggio imitating the echo of a harp, the “protagonist loudly bursts forth with recognition of the season’s entrance; here, the vocal line simultaneously reaches its highest notes and its first forte crescendo within just two demanding measures.” The composer repeats segments of the text several times, varying each occurrence, especially in terms of dynamics, to emphasize the protagonist’s elation.

Critics have suggested, “Mörike-lovers may consider this song a witless travesty of a beautiful poem.” However, the music is certainly charming and effective, and Schumann has left the innocence of his early songs in this set behind and the music has “grown into the dancing pulse of a girl’s first love song.” Until recently, it has been fashionable to consider the songs of 1849 a decline. “Schumann never again reached or even approached the level of his 1840 masterpieces” a scholar writes. “Other composers of comparable stature are believed to mature in their music; Schumann appears to deteriorate. A favoured explanation is mental illness…and the musical evidence seems to support a theory of progressive disorder from 1849 onward. And while Schumann is still a fine songwriter in 1849, he is no longer a great one. Sometimes, as in Goethe’s text from Faust, he treats great poetry rather cavalierly.”

Song of Lynceus the Watchman

I am born for seeing,

Employed to watch,

Sworn to the tower,

I delight in the world.

I see what is far,

I see what is near,

The moon and the stars,

The wood and the deer.

In all these I see

Eternal beauty,

And as it has pleased me,

I’m content with myself.

O happy eyes,

Whatever you have seen,

Let it be as it may,

How fair it has been!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

Robert Schumann: Lieder-Album fur die Jugend, Op. 79 – No. 24. Spinnerlied (Christina Landshamer, soprano; Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Andreas Burkhart, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Robert Schumann: Lieder-Album fur die Jugend, Op. 79 – No. 27. Lied Lynceus des Türmers (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young – Mignon

It has been said that Goethe’s character “Mignon” beautifully embodied the virtues of Romanticism. “From her simplicity, to her unbreakable loyalty and strength of emotions, she simultaneously embodies youthful innocence and mature longing, helplessness as an abused child and an ambiguous relationship with her protector… She gave voice to those in society who were otherwise ignored or forgotten.” Schumann composed “Mignon” to conclude his Album of Songs for the Young in the summer of 1849 amidst the uproar and danger of the Dresden uprising.” In his reading of the poetry and his musical setting there is no audible suggestion of decline. It might be somewhat taxing for untrained voices, as the melodic line is disjunct and widely spaced. In addition, the phrasing of the vocal lines and their interlinking with the piano part certainly calls for trained interpreters. Assumed mental deterioration aside, Schuman thought highly enough of his “Mignon” setting to place it at the head of his “Songs of Wilhem Meister,” Op. 98a.

Mignon

Do you know the land where the lemons blossom,

Where oranges grow golden among dark leaves,

A gentle wind drifts from the blue sky,

The myrtle stands silent, the laurel tall,

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

I long to go with you, my love.

Do you know the house? Columns support its roof,

Its great hall gleams, its apartments shimmer,

And marble statues stand and stare at me:

What have they done to you, poor child?

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

I long to go with you, my protector.

Do you know the mountain and its cloudy path?

The mule seeks its way through the mist,

Caverns house the dragons’ ancient brood;

The rock falls sheer, the torrent over it,

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

Our pathway lies! O father, let us go!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

No comments:

Post a Comment