It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Friday, November 26, 2021

4 Hands 4 More Piano Fun

by Georg Predota, Interlude

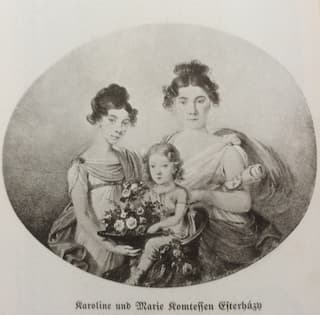

Marie and Karoline Esterházy

It is certainly telling that the earliest surviving music by Franz Schubert is the extended Fantasie D. 48 for piano duet. Composed at the age of thirteen, Schubert composed prolifically for the medium until his untimely death at the age of 31. For Schubert and his friends, four-hand piano music was a natural part of convivial evenings. Since this repertoire was almost exclusively destined for the private amateur salon market, however, a large number of these genial and charming works are still virtually unknown. Presumably written in 1818 or 1824, Schubert’s Variations D. 968a for piano four hands is one of series of compositions written for the two daughters of Count Johann Karl Esterházy. Schubert was engaged as music tutor to the two girls and spent two summers at the Count’s estate at Zseliz in Hungary. Schubert wrote to his friend Moritz von Schwind, “I have composed a big sonata and variations for four hands; the latter are enjoying great applause here, but since I don’t quite trust the taste of the Hungarians I’ll let you and the Viennese decide about them.”

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, 1952

Sketched in 1952 and completed in the spring of 1953, Poulenc’s Sonata for two pianos is dedicated to pianists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale “as much with friendship as with admiration.” Considered one of the most important piano duos of the 20th century, Gold and Fizdale commissioned and premiered a number of important works in the second half of the 20th century, including works by John Cage, Virgil Thomson, and Ned Rorem. As part of the tsunami of American artists, musicians and writers, the Duo traveled to Europe and arrived in Paris in 1948 with a letter of introduction to Germaine Tailleferre. A lunch with Francis Poulenc and Georges Auric was quickly arranged, which in turn lead to a number of works dedicated and composed for the Duo. Tailleferre wrote her Toccata for two Pianos and her Sonata for Two Pianos for Gold and Fizdale, while Poulenc contributed his own Sonata for Two Pianos for “the Boyz,” as he called them. The work was first introduced to the public on 2 November 1953 at London’s Wigmore Hall.

Francis Poulenc: Sonata for Two Pianos (François Chaplin, piano; Alexandre Tharaud, piano)

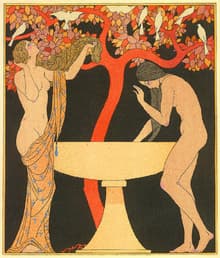

Chansons de Bilitis

Claude Debussy’s friend Pierre Louÿs published his Chansons de Bilitis in 1894. Louÿs claimed that the 143 prose poems were the work of a woman of Ancient Greece called Bilitis, and originally found on the walls of a tomb in Cyprus. Although this amiable case of literary fraud was quickly uncovered, his contemporaries were greatly impressed with the poems skillful and evocative blending of the antique and the modern, and the erotic with the spiritual. In fact, Louÿs sympathetic celebration of “lesbian sexuality earned him sensation and historic significance.” These poems not only inspired 3 operas, but also a number of settings for voice and piano. And Debussy added his three exquisite setting in 1897. To accompany a reading of twelve Bilits poems in 1900, Debussy wrote incidental music scored for two flutes, two harps and celesta. Soon after returning home from a trip to London, which would sadly be his last journey abroad, Debussy returned to his 1900 Bilitis music and reworked it into his Six Épigraphes Antiques for piano four hands. Critics have noted that these, “six pieces capture well the spirit of classical antiquity in cold, marmoreal and simultaneously sensual whole tone scales, modal structures and short repetitive motifs.”

Claude Debussy: Six Épigraphes Antiques (Genevieve Joy, piano; Jacqueline Bonneau, piano)

Brahms Pavillon on Lake Starnberg in Tutzing

Johannes Brahms spent his summer holidays of 1873 on the shores of Lake Starnberg in southern Bavaria. Here he managed to complete a key work in his development towards his first symphony. The Variations on a theme by Joseph Haydn Op. 56 might not actually have been based on a Haydn theme, but they are at the pinnacle of Brahms’s variations craft. In eight dense variations Brahms manages to liberate compositional rationality from any kind of effectual aesthetics. “One cannot just wait for inspiration to turn up,” Brahms once remarked, “but it needs to be earned legitimately, thanks to incessant work.” The original version called for two pianos with Brahms gradually envisioning the work as an orchestral piece. The reason was entirely practical and musical, as the counterpoint eventually becomes so intricate and pervasive that it requires orchestral forces to be heard clearly.

The young Beethoven, c. 1780

Craer’s Magazine of Music dated 2 March 1783 contains the first ever-printed notice pertaining to Ludwig van Beethoven. The correspondent writes, “Louis van Beethoven, son of the tenor singer already mentioned, a boy of 11 years and of most promising talent. He plays the piano very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well, and I need say no more than that the chief piece he plays is Das wohltemperirte Clavier of Sebastian Bach…. This youthful genius is deserving of help to enable him to travel. He would surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart if he were to continue as he has begun.” In 1787 Beethoven was sent to Vienna by the Archbishop of Cologne to take lessons with Mozart. However, the illness of his mother immediately forced his return home to Bonn. Finally in 1792, Beethoven relocated to Vienna to seek his fortunes in the imperial capital. He soon attracted a number of piano students, and he published the didactic Sonata for Piano four hands as Op. 6 with Artaria. It might come as a surprise that Maurice Ravel originally composed relatively few of his works for orchestra. In fact, some of his most recognized pieces are rearrangements of original piano versions. It has been suggested that Ravel approached composition like a painter approaches a canvas. The piano originals, it has been argued, became the equivalent of a charcoal outline to be colored at a later stage. This is certainly the case with Ravel’s major orchestral tribute to Spain, the Rapsodie espagnole, composed between 1907 and 1908. The origin of this composition was a “Habanera” for two pianos, which Ravel wrote in 1895. It was the first Ravel composition to be performed publicly, and it made a strong impression on Claude Debussy. In 1907, Ravel composed three companion pieces, and by October of that year, the two-piano version was completed. It took Ravel a further 4 months before he had fully orchestrated the work by February 1908.

Eleonor Bindman and Jenny Lin

With the piano taking center stage in the salons and living rooms of the 19th century, music became a widely accepted form of home entertainment. Realizing the full sonorities and orchestral potential of the instrument, it was also a way to actively make and hear music that would otherwise not be accessible. Reductions of chamber music and orchestral works allowed musicians and their audiences to experience a broad range of music. And when two people sit at one instrument sharing space and often the same notes, the interactive side of music making is elevated to a physical level. Composers ranging from Schubert and Brahms and from Rachmaninoff to Debussy made various piano 4 hands arrangements of their own music. Although J.S. Bach also produced a number of arrangements, the time had not yet come to explore the full potential of the piano. As such, a substantial number of composers and performers have taken up this delightful and satisfying task.

Scriabin

At the age of 16, Alexander Scriabin enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory. His musical talents developed rapidly, and he was mainly regarded as a pianist. A review of a concert on 28 February 1891 reads, “Henselt’s Piano concerto, whose unconventional virtuosic techniques make it one of the most difficult piano compositions, was played by Scriabin, student of Professor Safonov, with such calm and self-assurance that can only be expected from an experienced virtuoso. Scriabin definitely makes huge progress and not only with his technique; his playing is extremely charismatic, having all signs of purely artistic talent.” In addition, Scriabin made his first forays into composition, and that included a Fantasy in A minor for two pianos. Published only after his death, the work is described as “a dazzling exercise in ornated melody built upon a rock-solid harmonic base.”

(C) 2021 by Interlude

Classical Music in Cartoons

by Fanny Po Sim Head, Interlude

For years, film and television producers and writers have been using classical music to make their work more memorable. It should come as no surprise that some of our earliest memories of classical music might be from the cartoons we watched as children. From Beethoven to Wagner, cartoons have used this music not only as a charming background, but also as a point of focus, almost like another character.

In this article I’ve collected a few of my favorite musical cartoon collaborations. Let us know your favorite appearance of classical music in cartoons!

SpongeBob SquarePants

Spongebob and Gary

Classical music is so popular that it is frequently used in cartoons, including this award-winning cartoon, SpongeBob SquarePants (SpongeBob)! Premiered in 1999, Spongebob is one of the longest-running animated series in the United States. It is currently in its thirteenth season.

Created by former marine biologist and animator Stephen Hillenburg, the story follows the adventures of an accident-prone sea sponge named SpongeBob SquarePants. He and his pet snail Gary live together in a pineapple underwater.

The show has tapped into classical music repertoire often, from old to present, including Johann Strauss‘ The Blue Danube.

The show also commissioned Emmy nominated composer Gary Stockdale to write a piece for an episode called Suction Cup Symphony in season six. That episode features Squidward, an octopus, as well as an arrogant musician, who writes music for his symphony.

Marsha and the Bear

Marsha and the Bear

Originally from Russia, Marsha and the Bear is a famous cartoon all over the world. It has been translated to over twenty languages. Created by Oleg Kuzovkov, the story loosely follows a folk story of the same title. Marsha, a bright, mischievous little girl, is the main character of the story. She lives in the forest with her bear, who protects her and keeps her from getting into trouble. This sweet and funny cartoon has been on the air since 2009. Classical music has been used in many ways in the show, such as this electronic version of Chopin‘s Grand Waltz Brillante, Op.18, No. 1:

McDull: The Pork of Music

My Life as Mcdull

My Life as McDull is one of my favorite cartoon movies. Made in Hong Kong and created by Alice Mak and Brian Tse, McDull the piglet has become hugely popular ever since the movie was shown in 2001. The story of this piglet reflects the many lives of Hong Kong people. It also documents McDull’s childhood life, his dreams, and his positive attitude towards the future.

This theme song is adapted from Franz Schubert’s Moment Musicaux No.3 in F minor. A series of McDull movies were released after the success of My Life as McDull. The McDull series adapted much classical music, including this gem, the Sabre Dance, by Aram Khachaturian in McDull: The Pork of Music (2012).

The Simpsons

The Simpsons

This famous American TV show, The Simpsons, regularly features classical music in a satirical way. In the episode “The Seven-beer Snitch” in season 16, the writers of the show aim their satire at the contemporary concert audience. This scene shows the audience leaving after hearing the first few measures of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (because that’s part of the piece everyone knows), and then running out of the concert hall when they learn an “atonal masterpiece” is on the program. The cultural commentary, as always, is sharp and funny!

Not only featuring classical music but a music history lesson about Mozart and Salieri is also taught in the episode “The Magical Musical Tour” in season 15. Mozart was played by Bart who performed the Sonata in A major, K.311. Some of Mozart’s compositions were replaced with different titles such as The Musical Fruit (The Magic Flute) and Beans, Beans, the Musical Fruit (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik). You can also hear a fragment of Mozart’s Requiem in addition to Beethoven’s Ode To Joy and a snippet of the Fifth Symphony in that episode.

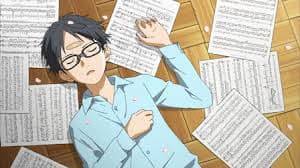

Your Lie In April

Your Lie In April

This Japanese anime television series was adapted from the manga with the same title created by Naoshi Arakawa. Your Lie In April is about Kōsei Arima, a child prodigy and became famous after winning major piano competitions. However, he lost his ability to play following his mother’s passing. The story focuses on his friendship and romantic relationship with Kaori Miyazono, who encourages Kōsei to return to the musical world. The tv series was released in 2014-2015. It included many classical works, including Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op.28, and Mozart’s Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.

Adventure Time

Jake the Dog

Adventure Time is another popular animated show in the 2000s. It has 283 episodes which have lasted for ten seasons since 2007. Produced by Pendleton Ward, Adam Muto, and Fred Seibert. About the adventures of a boy named Finn and his best friend Jake the Dog. This animated show is full of humor and entertaining to watch! Classical music is often played in the show. In season 2, Food Chain, when a magician transforms Finn and Jake into birds, and an electronic version of Mozart’s Queen of the Night’s Aria from the opera The Magic Flute is played.

In the show, Jake the dog is a magical dog who is already 28 years old. He is also a good fighter and a skilled musician. In this excerpt, he plays some Moonlight Sonata, the theme of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik.

The Family Guy

Family Guy

As a pianist and a piano teacher, I am always curious about the lives of other piano teachers. In the Family Guy, Lois (Peter’s wife) is a piano teacher. Her playing and teaching are featured occasionally throughout the show. In one episode, Lois made Peter drunk during a student recital as he could play better. I wish it could be that easy!

In fact, Peter is portrayed as a very musical person who can play several other instruments pretty well. In this clip, Peter plays the violin in a quartet for a wedding gig, and you can hear his spectacular technique on Mendelssohn‘s Wedding March. Well, growing up in such musical family, the show also features Stevie the son and his musical talent. You cannot miss this episode that Stevie mimics “Mozart” in the movie Amadeus. Funny enough, you will hear some works written by Beethoven in addition to some of Mozart’s works.

(C) 2021 Interlude

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

Rossini and His Overtures

by Georg Predota, Interlude

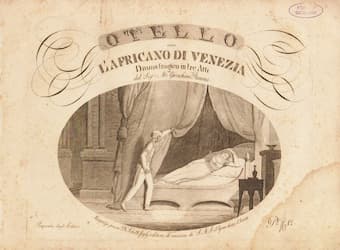

Rossini’s Otello

We celebrate Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) as one of the most successful and popular operatic composers of his time. And although you might never have actually seen or heard a complete Rossini opera, I am sure you know a good many of his overtures. In fact, the overtures have long been staples of the orchestral repertory and much more frequently performed than the operas to which they belong. It is a curious situation in that the reputation of his dramas has never equaled the sweetness “of their melodies, the richness of their harmonies, the brilliance of their orchestration, and the power of their rhythms.” We do know that almost all of his overtures make use of musical elements and melodies that appear somewhere in the opera, which begs the question if Rossini composed the overture before or after he had completed the opera? According to legend, that’s exactly the question a young composer asked Rossini, who described six different ways of composing overtures. Rossini apparently said, “I composed the overture to Otello in a little room in which that most ferocious of all managers, Barbaja, shut me up with a dish of macaroni and told me that he would let me out only after the last note of the overture had been written.” As a point of reference, Otello was first performed in Naples at the Teatro del Fondo in 1816, and the notorious Barbaja was indeed involved. As far as the overture goes, this one was clearly written after the opera had been completed.

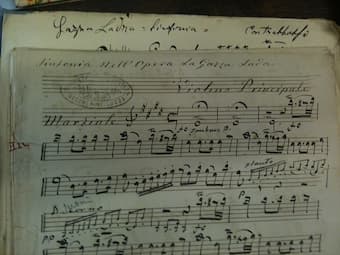

Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra

The same process was apparently at work with the overture to La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie). Rossini reports that he “wrote the overture to Gazza Ladra, on the very day of the first performance of the opera in the wings of the Scala Theatre in Milan. The manager had put me under the guard of four stagehands who were ordered to throw down the music pages, sheet by sheet, to copyist seated below. As the manuscript was copied, it was sent page by page to the conductor who then rehearsed the music. If I had failed to keep the production going fast, my guards were instructed to throw me in person down to the copyists.” Fortunately, Rossini was able to keep up, and therefore managed to witness the huge success of the opera. Rossini himself was thrilled by his opera and a few days after the première wrote in an excited letter to his mother “that it was so full of music that one could make three or four operas from it,” and that it was “the most beautiful music I have written so far.”

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville

Rossini’s opera buffa The Barber of Seville is primarily known today for its rousing overture. However, the premiere on 20 February 1816 at the Teatro Argentina in Rome was a disaster! The next day Rossini wrote to his mother, “Last night my opera was staged and it was solemnly booed, what mad, what extraordinary things are to be seen in this country. I will tell you that in the midst of it all the music is very fine and already people are talking about its second evening when the music will be heard, something that did not happen last night, from the beginning to the end without the constant noise accompanying the whole performance.” Rossini was entirely correct about the second performance, as it was an unqualified triumph. But how did Rossini compose the famous overture? He writes, “I made my task easier in the case of the overture to the Barber of Seville, which I left unwritten; instead I made use of the overture to my opera Elisabetta, which is a very serious opera, whereas the Barber of Seville is a comic opera.” In fact, the overture is actually twice re-cycled as he had originally written it for the opera Aureliano in Palmira of 1813.

Rossini’s Le Comte Ory

Rossini’s fourth opera for Paris, Le Comte Ory, was first staged at the Paris Opéra in August 1828. Set in thirteenth-century France, the opera deals with the attempts of Count Ory to woo the Countess Adèle, whose husband is away on a crusade. There is much disguising—including hermits and nuns—and everybody manages to run away just before the husband of the Countess returns. The “Introduction” is well matched to the plot, its outer sections suggesting the Count’s cunning exploits, with a martial passage at its heart, the returning opening section ending in the plucked notes of the strings.” How did Rossini go about composing the “Introduction?” According to the composer, “I composed the overture to the Comte Orly while fishing in the company of a Spanish musician who the whole time talked incessantly about the Spanish political situation.” Really doesn’t tell us much about the creative process, but it’s a nice anecdote nevertheless.

Rossini’s William Tell

When we talk about instrumental favorites in contemporary concert halls, we invariably stumble across the overture to William Tell. While the opera itself has been largely forgotten, the overture owns much of its popularity to varied incorporations within expressions of popular culture. Let’s not be deceived, however, because the popular appeal of Rossini’s William Tell Overture was instantaneous. It was immediately published independently from the opera, and Franz Liszt promptly fashioned his famous piano transcription. Rossini tells us that he “composed the overture to William Tell in the lodgings on the Boulevard Montmartre filled night and day with a crowd of people smoking, drinking, talking, singing, and bellowing in my ears while I was laboring on the music.”

Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto

Friday, November 19, 2021

Schubert’s Illness and His Last Piano Sonatas

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Franz Schubert

On 19 November 1828, Franz Schubert died at the age of 31 in his brother’s flat in Vienna. He had been seriously ill for some time, with the primary symptoms of syphilis presenting themselves as early as December 1822. Premonitions of death consistently haunted Schubert following his diagnosis, and he wrote to a close friend, “I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, a man whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain, whose enthusiasm for all things beautiful is gone, and I ask you, is he not a miserable, unhappy being? Each night, on retiring to bed, I hope I may not wake again, and each morning but recalls yesterday’s grief.” His physical and mental health oscillated between hope and despair, and Schubert took to bed with a fever on 5 November. Suffering from tertiary syphilis and the effects of highly toxic mercury treatment, Schubert passed away at 3pm on 19 November. His final and horribly painful days in November 1828 included bouts of delirium, ceaseless singing, and moments of great lucidity when he was working on his compositions. Astonishingly, with the period between the spring and autumn of 1828, Schubert composed his last major compositions for solo piano, the sonatas D 958, 959 and 960.

Portrait of Schubert by 3D Sculptor Hadi Karimi

Schubert’s three last sonatas are “cyclically interconnected by diverse structural, harmonic and melodic elements tying together all movements in each sonata, as well as the three sonatas, respectively; consequently, they are often regarded as a trilogy. By including specific allusions to his earlier compositions, Schubert appears to have crafted three highly personal and autobiographical works. Scholars and researchers have even suggested that the sonatas follow specific psychological narratives. In musical and structural terms, all three sonatas share a common dramatic arc, “making considerable use of cyclic motives and tonal relationships, and weave specific musical ideas into the developing narrative.” Each sonata unfolds in four movements, with the exposition of the opening movements exploring two or three thematic and tonal areas. Themes are irregularly constructed and digress into far-flung harmonic regions. Development sections violently plunge the listener into new tonal areas, and a new theme based “on a melodic fragment is presented over recurrent rhythmic figuration, and then developed, undergoing successive transformations.” The opening movements of all three sonatas resolve all internal conflicts and conclude in quiet peacefulness.”

Schubert at the Piano – Gustav Klimt (1899)

The slow movements of all three sonatas are cast in tonally remote keys, and feature two contrasting sections in key and character. In his third movements, Schubert references dances, including “playful figurations for the right hand and abrupt changes in register.” The themes of Schubert’s Finale movements are characterized by “long passages of melody accompanied by relentless flowing rhythms.” Structural and musical similarities aside, the last Schubert sonatas illustrate powerfully emotional states with the music weaving in and out of dreams and memories. Given the proximity of these sonatas to Schubert’s death, they have been read against a background of a psychological or biographical narrative.

Schubert’s death mask

It has been suggested that the sonatas “portray a protagonist going through successive stages of alienation, banishment, exile, and eventual homecoming, or self-assertion. Discrete tonalities or tonal strata, appearing in complete musical segregation from one another at the beginning of each sonata, suggest contrasting psychological states, such as reality and dream, home and exile, etc.; these conflicts are further deepened in the ensuing slow movements. Once these contrasts are resolved at the finale by intensive musical integration and the gradual transition from one tonality to the next, a sense of reconciliation, of acceptance and homecoming, is invoked.” It is entirely plausible that the sonatas do convey Schubert’s feelings of loneliness and alienation, and that the process of composition became a kind of psychological therapy. And if you are looking for a depressing postscript, the sonatas D 958, 959 and 960 were not even published until ten years after Schubert’s death, and they were greatly neglected in the 19th century.

Thursday, November 18, 2021

McDonald’s tweeted ‘All I Want for Christmas’ as music notes and got trolled by Mariah Carey

By Sophia Alexandra Hall

@sophiassocialsG - B - D - F - G - F - D - B - G - C - D - G - D

Ah, Christmas; the smell of French fries, ketchup packets, and a Big Mac in a pear tree.

Or at least that’s what McDonald’s wants you to think of, as it announced its Christmas menu collaboration for 2021 last night.

The cryptic message G - B - D - F - G - F - D - B - G - C - D - G - D was posted on Twitter, and fans were unsurprisingly puzzled.

Some Twitter users immediately started guessing what the global fast-food giant was trying to say.

Others, such as American singer-songwriter Charlie Puth, used this as an opportunity to ask that their favourite McDonald’s meal item remain on the menu forever...

Then, musical fans in the comments section began to realise the sequence could actually be musical, and many took to their pianos to figure the melody out.

But it wasn’t until this tweet from the Christmas queen, Mariah Carey herself, that everyone began to realize what had happened.

G - B - D - F# - G - F# - D - B - G - C - D - G - D are the notes (in G major) which open the Christmas classic, Mariah Carey’s All I Want for Christmas is You.

The 13 notes are played on a glockenspiel as an introduction to the four-minute anthem.

As well as accidentally giving the public a lesson in how accidentals can change the entire context of a song, McDonald’s used the tweet to launch their Christmas menu collaboration with Carey this December.

“Just like McDonald’s brings people around the table with their favourite orders, Mariah’s music connects us all during this time of the year,” said McDonald’s USA Vice President Jennifer Healan. “We’re so excited to team up to bring even more holiday cheer to our fans.”

Starting on 13 December, McDonald’s customers in the US will be able to access a Twelve Days of Christmas-inspired ‘Mariah Menu’ of free food, if they spend a minimum of $1 on the fast-food chain’s app.