Johann Sebastian Bach

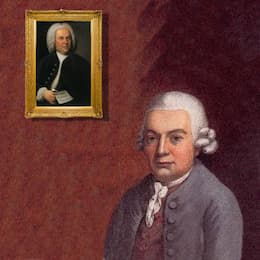

Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714-1788) described his father’s household in Leipzig as a “pigeon coop.” People were constantly swarming in and out all the time, and he told the Bach biographer Forkel, “with his many activities Bach hardly had time for the most necessary correspondence, and accordingly would not indulge in lengthy written exchanges. But he had the opportunity to talk personally to good people, since his house was full of life.”

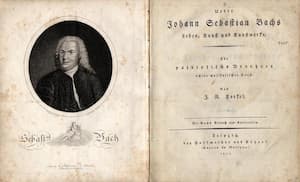

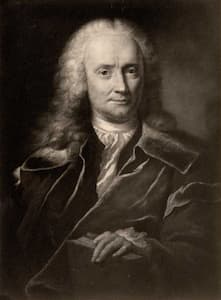

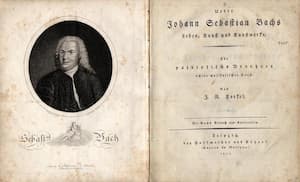

Forkel: J.S. Bach Biography

Johann Sebastian and his wife Anna Magdalena Bach kept an open house, welcoming friends and colleagues from near and far. “No master of music was apt to pass through Leipzig without making Bach’s acquaintance and letting himself be heard by him.” And that included a good number of the leading figures in contemporary German musical life, including Carl Heinrich and Johann Gottlieb Graun, Franz Benda, Johann Joachim Quantz and the famous husband and wife team of Johann Adolph Hasse and Faustina Bordoni, who came to Leipzig several times. The Bach family frequently entertained at home, and that always included house concerts. And we do know that Carl Philipp Emanuel performed in his father’s Concerto for two Violins, BWV 1043.

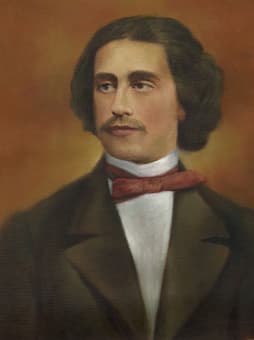

Johann Nikolaus Forkel

From 1736 until his death, Johann Sebastian Bach held the title of Royal Polish and electoral Saxon Court Composer. The composer actually never traveled to the Kingdom of Poland or the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, governed by Augustus II (Augustus the Strong,) and his son Augustus III. However, when Augustus III succeeded his father in 1733, he announced a surprise visit to Leipzig one year later. Bach immediately went to work and in a mere three days composed his secular cantata “Preise dein Glücke, gesegnetes Sachsen,” (Praise your good fortune, blessed Saxony) BWV 215.

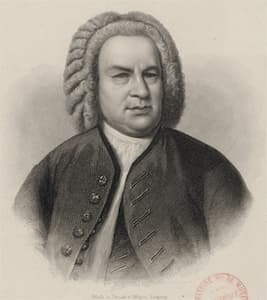

August Weger: J.S. Bach

This cantata was first performed on 5 October 1734, in front of the Apels Haus, the Elector’s palace on the market square in Leipzig. Apparently, Augustus III was overjoyed, and he wrote in his official account that he had been “warmly pleased.” Bach had already been in contact with Augustus III in 1733, when he presented the manuscript of a “Missa of Kyrie and Gloria” to the monarch. These movements later became part of the B-minor mass, and Bach eventually did get his “Royal Polish” 1736 appointment.

St. Michaelis monastery in Lüneburg

Johann Sebastian Bach lost both parents before the age of ten. He spent the next five years with his older brother Johann Christoph in the town of Ohrdruf. And at school, he became best friends with Georg Erdmann. When Johann Christoph’s ordered his younger brother out of the house, the two friends decided to walk to Lüneburg, a distance of almost 350 miles. There they joined the choir of the wealthy Michaelis monastery, which provided free places for poor boys with musical talent. The boys were inseparable until their paths diverged in 1702. Bach moved back to Thuringia, and we have no idea what happened to Erdmann over the next 27 years.

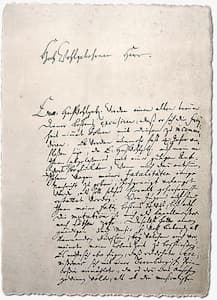

Bach’s letter to Erdmann

Bach and Erdmann had lost touch, but their friendship endured, as we learn from two surviving letters dating from around 1730. “Dear Friend,” Bach writes, “you might excuse an old friend, who allows himself to bother you with this letter. Almost four years are gone, since you answered my last letter. I remember you asked me to report about my difficulties, which I would like to do now. Since our youth you know my career, until my change as a bandmaster in Koethen…” Bach also reports to Erdmann about personal matters, “I am married for the second time… From my first marriage three sons and one daughter are still living, whom you saw in Weimar years ago. From my second marriage one son and two daughters are living. My oldest son is studying law; the two others still go to school, one in the prima; the other one in the secunda. The children from the second marriage are still little; the oldest is six years of age. They are all future musicians.” The “Partite diverse” BWV 766 dates from around 1700, at a time when both Ermann and Bach were studying at the Michaelis School.

Johann Matthias Gesner

During his time in Weimar, Bach became good friends with the eminent philologist and scholar Johann Matthias Gesner (1691-1761). An expert in Semitic languages, classical literature, metaphysics and theology, Gesner became librarian and vice-principal at Weimar. Eventually, Gesner was appointed rector at the School of St. Thomas, and he therefore became Bach’s boss. As it turns out, Gesner was the only superior in Bach’s 27 years of service in Leipzig who recognized, admired and fostered his greatness. Gesner freed Bach from many unnecessary responsibilities, and since he was an admirer of Bach’s music, “he allowed Bach to assume his social position as a truly great musician and to assert his influence at the school as well.” Gesner raised Bach’s salary, allowed him to travel, freed him from teaching Latin, and asked for advice on updating the curriculum, admissions, and administrative approaches. In fact, Gesner published an extensive description of Bach in 1738, placing the composer far above the musical gods of Greece. In turn, to celebrate Gesner’s 40th birthday on 9 April 1732, Bach adapted his Cantata “Soar upwards in your joy” to celebrate the occasion.

Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen

In 1719, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen sent Johann Sebastian Bach on an errand to Berlin. Bach was placed in charge of negotiating for a new harpsichord for the court, and he tried out a number of instruments in the presence of Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt. We don’t know what Bach played on that occasion, but he was invited to send in some compositions.

Christian Ludwig, Margrave of

Brandenburg-Schwedt

Initially, Bach did not respond to the commission as he himself said, he “took a couple of years.” Bach changed his mind in 1721, however, as Prince Leopold summarily dismissed him from his services. As such, Bach was forced to look for employment opportunities elsewhere, and he sent the Margrave six instrumental compositions. These compositions became known as the Brandenburg Concertos, and they represent a compendium of highly original and individual compositions for a varied combination of instruments. According to the composer “they were written to exploit the resources of Cöthen.” However, these resources did not seem to have been available to the Margrave of Brandenburg. As such, Bach received no thanks, no fees and no employment offer.

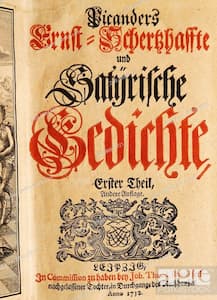

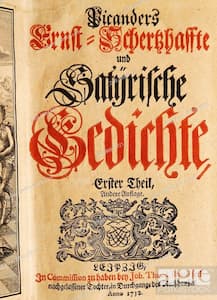

He was born Christian Friedrich Henrici in Dresden in 1700, but everybody knew him under the pseudonym “Picander”. Picander started his poetic career in Leipzig in 1721, and in time, he would become one of Bach’s most important poets. He probably wrote his first text for Bach in 1723 but there are still some uncertainties as to the authorship of texts during Bach’s first years in the city. However, by 1725 Bach and Picander were definitely working together.

Picander: Book of Poems, 1732

Their collaborations produced some of the most important works in the Lutheran tradition, including the St. Matthew Passion (BWV 244), the funeral music for Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, and the St. Mark Passion (BWV 247). Picander claimed that Bach “set a whole cycle of his cantata texts in 1729.” Since only nine of these Bach settings are known to have survived, Picander’s claim must be approached with some caution. Their collaboration, however, wasn’t limited to religious texts, but also produced a number of secular works as well. For one, there is the well-known “Coffee Cantata,” and the delightful “Peasant Cantata,” written at a time when Picander served as a Liquor Tax Collector and Wine Inspector.

Georg Böhm

During his early years at Lüneburg, Bach was probably taking organ lessons from Georg Böhm (1661-1733). Böhm was principal organist at the Johanniskirche in Lüneburg, and the young Bach studied at the Michaelis School between 1700 and 1703.

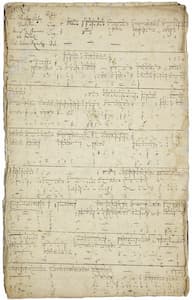

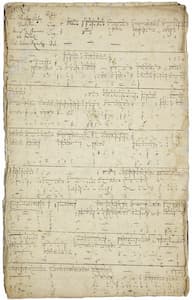

First page of Reincken’s An Wasserflüssen Babylon, with an endnote in J. S. Bach’s hand

Although no formal connection existed between these two institutions, Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel reported to the Bach biographer Forkel in 1775, “My father loved and studied the works of the Lüneburg organist Georg Böhm.” Strong and clear evidence of this teacher/student relationship emerged on 31 August 2006 when the earliest known Bach autograph was discovered. It is a copy of Reincken’s famous chorale fantasy “An Wasserflüssen Babylon,” and Bach signed it “Il Fine â Dom. Georg: Böhme descriptum ao. 1700 Lunaburgi.” It is clear that Bach knew Böhm personally, and they apparently became close friends. This friendship seems to have lasted for many years, as Bach named Böhm as his northern agent for the sale of his keyboard partitas No. 2 and 3 in 1727.

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.

Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach

When Bach’s maternal uncle died in Erfurt, he left Bach a substantial amount of money. As such, Bach was able to marry Maria Barbara on 17 October 1707 in the village of Dornheim, near Arnstadt. Their marriage, by all accounts, was a contented one and four of their seven children lived into adulthood, including Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

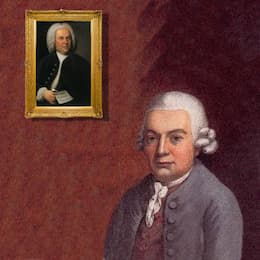

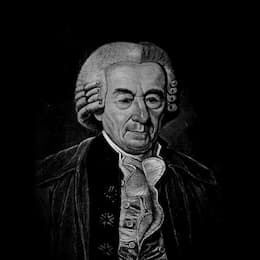

C.P.E. Bach

In 1720, Bach accompanied his employer Prince Leopold to the spa in Karlsbad. When he returned two months later, he discovered that Maria Barbara had died from a sudden illness, and that she was already buried at Köthen’s Old Cemetery. She was only 35, and the heart-broken composer gave voice to his grief in the monumental “Chaconne,” the fifth and final movement of the Partita in D minor for solo violin. Play

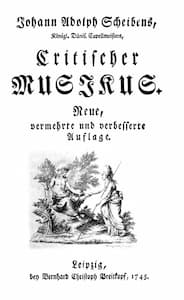

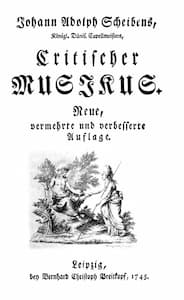

Johann Adolph Scheibe

The composer, organist, theorist and music critic Johann Adolph Scheibe (1708-1776) considered J.S. Bach and George Frideric Handel to be the finest composers of keyboard music. Yet, on 14 May 1737, Scheibe published a weighty criticism of Bach’s music, claiming “by his bombastic and intricate procedures he deprived music of naturalness and obscured their beauty by an excess of art.”

Title page of Scheibe’s music criticism, 1745

Bach was not amused, and he urged his friend, the Leipzig lecturer in rhetoric Johann Abraham Birnbaum (1702-1748) to write a response. That response was printed in January 1738, and Bach distributed the article among his friends and acquaintances. It discusses the issues of naturalness and artificiality in Bach’s style, and his “definition of harmony as an accumulation of counterpoint,” made an important statement about the unique character of Bach’s compositional art. Scheibe’s attack, as it turned out, stimulated a good bit of sympathy for Bach, and in the end he published a conciliatory review of the Italian Concerto, which included the apology “I did this great man an injustice.” Play

Electress Christiane Eberhardine

In order to commemorate the death of the Electress Christiane Eberhardine in 1727, the University of Leipzig planned an extended memorial ceremony. The Electress was somewhat of a religious celebrity, as she had remained a Protestant when her husband, August the Strong of Saxony, had converted to Roman Catholicism.

Johann Christoph Gottsched

Bach was commissioned to set a text by the Leipzig professor poetry, Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700-1766). That commission proofed to be controversial, as the university director of music Johann Gottlieb Görner, considering himself to be Bach’s superior, tried to bar Bach from taking any role in the service. The council thought otherwise and Bach retained the commission. As such, Bach performed the two parts of his Funeral Ode (BWV 198) on 17 October 1727. This cantata unfolds in ten sections, and includes chorales, recitatives and solo arias for soprano, alto, and tenor. Even the bass gets a lengthy accompanied recitative that borders on being an aria itself.

(To be continued!)

%20(1).jpg)

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.

Maria Barbara Bach (1684-1720) was the second cousin of Johann Sebastian Bach. She had been orphaned at an early age and was sent to live with relatives in Arnstadt. Johann Sebastian met her after his appointment as church organist in 1703, and for a time they apparently lived in the same house, as relatives do. In 1706, Bach was severely reprimanded for inviting a “strange maiden” into the church organ loft to “make music.” Scholars today believe that the maiden in question must have been Maria Barbara.