It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, January 18, 2025

While My Guitar Gently Weeps (Taken from Concert For George)

Big, Bigger, HUGE OPEN AIR CONCERTS | OUTSTANDING VOICES - The Maestro

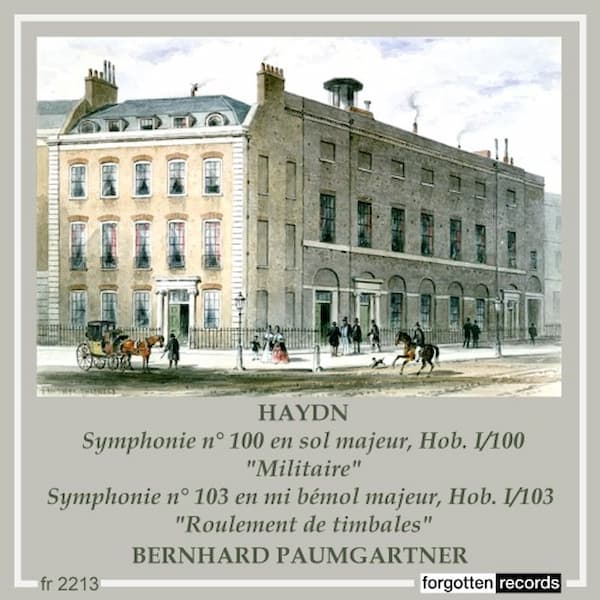

Impressing London: Haydn’s Symphony No. 100

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Thomas Hardy: Haydn, 1791 (London: Royal College of Music)

He had been commissioned by Johann Peter Salomon to write 6 new symphonies for the start of Salomon’s new subscription season. Haydn had met Salomon when the impresario met him in Vienna and succeeded in getting him to travel to England, first in 1791—1792 and then in 1794–1795. The acquaintance suited both – Haydn needed the exposure, and Salomon needed material for his concerts. For Salomon and London, Haydn wrote 12 symphonies (Nos. 93 to 104), first known as the Salomon Symphonies and now as the London Symphonies.

Thomas Hardy: Johann Peter Salomon, ca 792 (London: Royal College of Music)

Symphony No. 100 in G major was played on 31 March 1794 in the Hanover Square Rooms, i.e., in the heart of fashionable London. The original title for the work was the Grand Military Overture, due to the use of kettledrums and other percussion in the second movement. The end of the last movement sees the reappearance of the kettledrums and military percussion, tying the work together.

The final movement is a rondo, and the recurring main theme became widely popular in England, where it would appear as a dance theme in ballrooms around the country, anxious to reflect what was happening in London.

This recording was made in 1960, with Bernhard Paumgartner leading the Camerata Academica of the Salzburg Mozarteum.

Bernhard Paumgartner

Bernhard Paumgartner (1887–1971) was a leading Austrian composer, conductor, and musicologist. He taught at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, where he was Herbert von Karajan’s composition teacher and brought out his conducting skills. He was an important musical focus for the city, being one of the founders of the Salzburg Festival.

The Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg has a very direct connection with the Mozart family – it was founded in 1841 with the help of Wolfgang’s widow Constanze and his sons, Franz Xaver and Karl Thomas, as part of the Cathedral Music Association and Mozarteum that Constanze was promoting. The orchestra was named the Mozarteum Orchestra in 1908.

Performed by

Bernhard Paumgartner

Camerata Academica du Mozarteum de Salzbourg

Recorded in 1960

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Six Women In Brahms’s Life

by Emily E. Hogstadt, Interlude

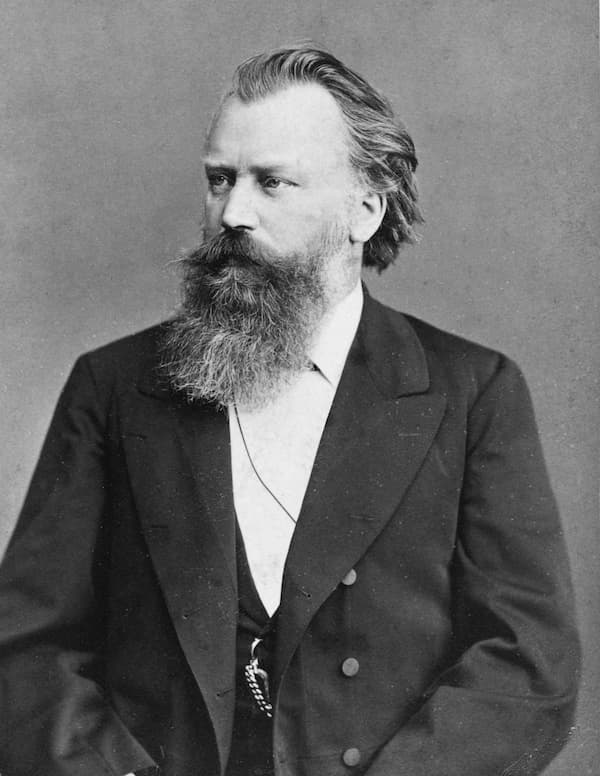

Johannes Brahms, c. 1885

And yet, despite his best efforts to stay free from emotional attachments to women, over the course of his life, he had deeply meaningful relationships with several of them.

Today, we’re looking at six of the women he was closest to and how they impacted his life, work, and music.

Christiane Nissen Brahms (1789-1865)

Christiane Nissen Brahms

Christiane Nissen was born to a tailor in Hamburg, Germany, in 1789.

She began working as a seamstress when she was just thirteen. During her twenties, she worked as a servant before returning to seamstress. Eventually, she moved in with her sister and brother-in-law and helped to run their shop, where they sold sewing notions.

To make some extra money, the family took in a lodger. He was a musician by the name of Johann Jakob Brahms. Eight days into his stay, he proposed to Christiane.

The proposal was surprising, to say the least. He was 24, she was 41. But she accepted, and they were married soon afterward, on 9 June 1830. They would have three children together: Elise, Johannes, and Fritz.

Brahms biographer Jan Swafford describes Christiane as “small, sickly, gimpy from a short leg, plain of face though she had enchanting blue eyes.” But she was a talented cook and housekeeper, and Johannes loved her deeply.

Unfortunately, her marriage deteriorated by the 1860s; the age difference and other issues caught up with the couple, and they separated. She died in 1865 after having a stroke.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896)

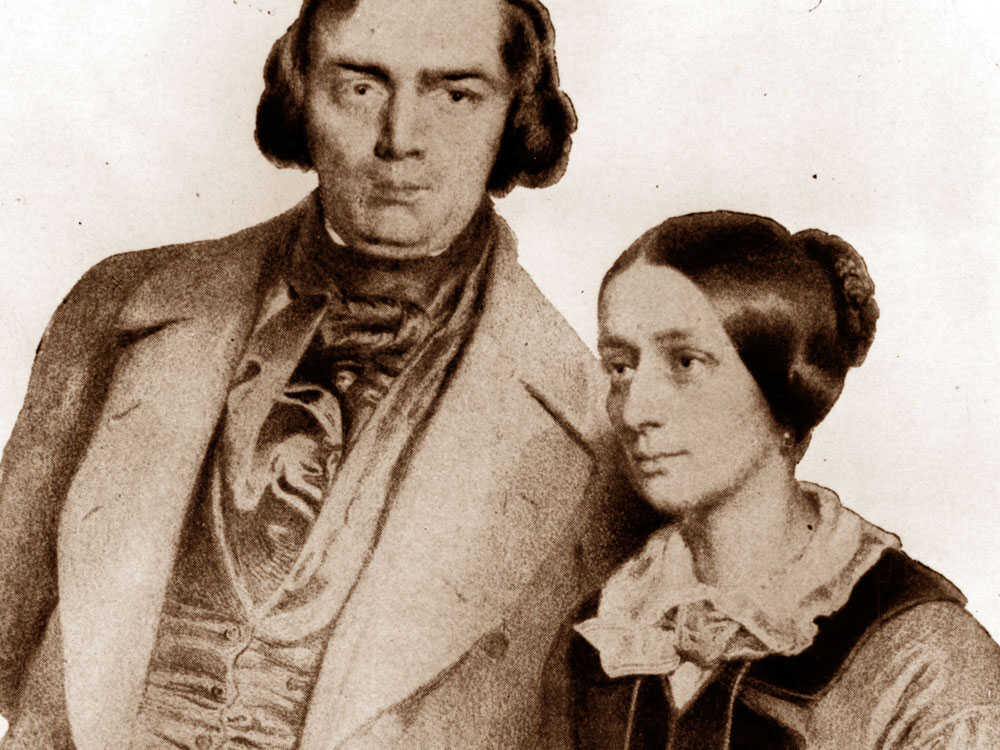

Robert and Clara Schumann

Clara Wieck Schumann was born to Friedrich Wieck, a piano teacher and music store owner, and his wife, singer Mariane.

Wieck was determined to make his daughter into a prodigy pianist as a kind of walking advertisement for his methods. He got very lucky: Clara became one of the most celebrated piano prodigies of her era.

As a teenager, she fell in love with one of her father’s students, Robert Schumann. Despite her father’s protestations, she married him in 1840.

On 1 October 1853, Clara and Robert met a 20-year-old Johannes Brahms, who nervously visited their home to network. The Schumanns were immediately taken by the music of this young genius from Hamburg. They invited Brahms to stay for a few weeks.

Robert Schumann believed him to be the future of music, and he wrote an article saying as much that was distributed in a magazine called the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

Brahms was starstruck by Robert’s faith in him…and, awkwardly, found himself falling in love with Clara.

Unfortunately, Robert Schumann’s mental health, never good, deteriorated drastically over the next few months. He attempted suicide in February 1854 and agreed to be admitted into an asylum. He would never return home.

After Robert’s departure, Brahms stayed to comfort Clara – who was pregnant at the time – and help with the children. Robert died in the summer of 1856.

We don’t know exactly what conversations Brahms had with Clara during this time. We do know that the idea of being in a marriage where his wife would out-earn him was unappealing, and Clara didn’t want any more children. Ultimately, they decided not to marry.

However, they stayed close friends for the rest of their lives, and neither of them married anyone else.

Elise Brahms Grund (1831-1892)

Elise was the eldest child of Johann Jakob and Christiane Brahms, born in February 1831, eight months after her parents’ wedding.

She suffered from headaches and was often bedridden with chronic pain. Because of her health issues, combined with the sexist mores of the time, she wasn’t able to get a good education. Christiane’s purportedly affectionate nickname for her was “the fat dumb peasant.” Her little brother Johannes, however, loved her.

In the 1860s, her parents split, although they never formally divorced. Elise’s mother was her ally in the household. The rift in the household deepened after Johann Jakob refused to pay for their expenses.

Unfortunately for Elise, her mother died suddenly of a stroke in 1865. Her father remarried. The situation left her vulnerable, and she ended up renting a room from friends, being subsidised by Johannes.

In 1871, when she was forty, she married a widowed watchmaker named Christian Grund, who was twenty years her senior. Johannes urged her not to, believing she was too naive and inexperienced to be a successful wife and mother. He even offered to pay for her room and board at a convent. (Clara Schumann, on the other hand, perhaps remembering how her father had once disapproved of her marriage to Robert, urged Johannes to support his sister.)

Happily, Johannes’s doubts were misplaced, and the marriage was happy. The two even had a child together, but unfortunately, the baby died a few days after it was born.

Her husband died in 1888 and she died in 1892. The letters Johannes had written to her were all returned to him after her death. Interestingly, although Brahms burned most other correspondences, he couldn’t bring himself to burn Elise’s.

Agathe von Siebold Schütte (1835-1909)

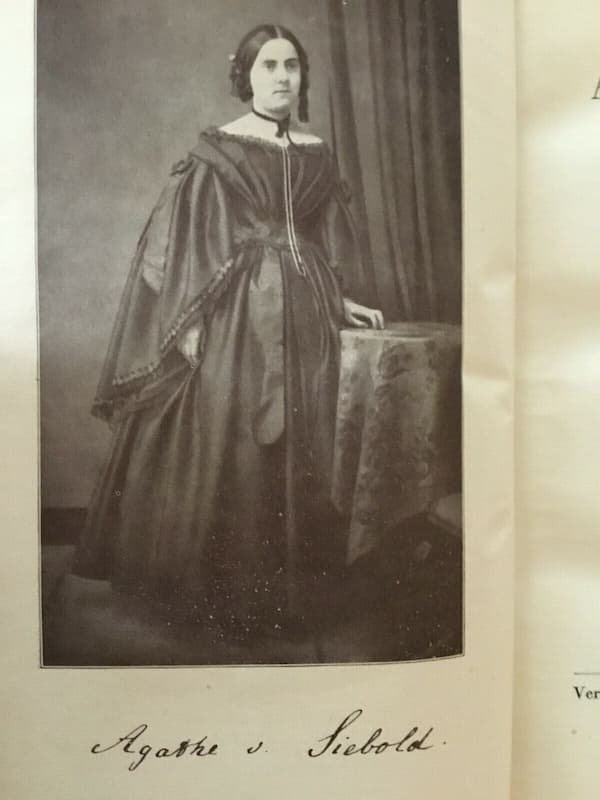

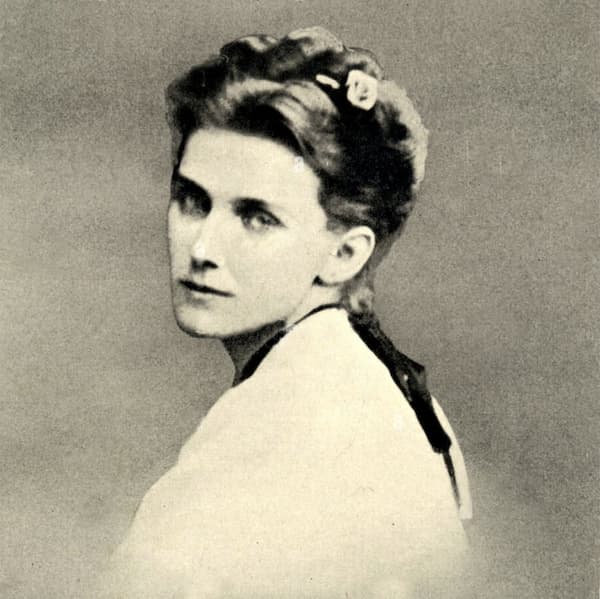

Agathe von Siebold Schütte

In July 1858, two years after the death of Robert Schumann, Brahms went to the town of Göttingen to visit friends and conduct the local women’s chorus. Clara Schumann, her composer brother, and five of her children also came with her.

During the trip, he befriended one of the sopranos in the chorus, a young woman named Agathe von Siebold. She had lovely dark hair, an attractive figure, and a playful sense of humour. She was also an amateur composer.

Their friend group stayed out late into the summer evenings, laughing and playing games, and Brahms and Agathe soon started flirting. However, he gave away to her that he still had Clara on a pedestal, telling Agathe at one point that he had to also walk with Clara occasionally so she wouldn’t get jealous.

He was right: Clara was so upset when she caught Brahms and Agathe embracing that she abruptly cut the vacation short.

After New Year’s, her family politely encouraged Brahms to propose, so that there would be no risk to their daughter’s reputation. He obliged, but they didn’t set a date for the wedding.

Unfortunately, simultaneously, Brahms experienced the relative failure of his first piano concerto. He claimed he could never face a wife after enduring any similar professional failures.

He wrote Agathe a rather appalling letter with the lines, “I love you! I must see you again! But I must not wear fetters!” Agathe interpreted this as shorthand for “Be my mistress, but not my wife.” She replied by sending her engagement ring back to him. The marriage was off.

She never forgot the relationship. In fact, later in life, she wrote a novel inspired by it. As for his part, Brahms included a theme made out of the letters of Agathe’s name in several musical works, including his second string sextett.

Julie Schumann (1845-1872)

Julie Schumann

Julie Schumann was Robert and Clara Schumann’s third child. She had been seven years old when her father left home for the asylum and Johannes Brahms moved in to help her mother.

Unfortunately, Julie’s health was poor. She traveled to stay with family friends in more southern climates, hoping to grow stronger.

During one of those trips, she met an Italian count, who fell in love with her. In 1869, she married him.

Johannes Brahms served as witness. Little did Julie know that doing so was torture. He’d fallen in love with her, but, given the complicated dynamics at play, he hadn’t verbalised his love fast enough – and now she was lost to him forever.

Johannes Brahms: Alto Rhapsody

He had confusing romantic feelings for Julie that he never really verbalised, instead choosing to write them into his Alto Rhapsody.

He wrote to his publisher, “Here I’ve written a bridal song for the Schumann countess – but I wrote it with anger, with wrath! What do you expect!”

Clara Schumann had feared that childbearing would weaken Julie, and tragically, her fears were well-founded. She had two children, her health weakened, and she died of tuberculosis in Paris in 1872 when pregnant with her third.

Learn more about what happened to the Schumann children.

Elisabeth von Stockhausen Herzogenberg (1847-1892)

Elisabeth and Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Elisabeth von Stockhausen was born in 1847. She was a musical child from a musical family (her father had studied piano with Chopin), and in the winter of 1863-64, she began taking piano lessons from Johannes Brahms. He found her very attractive and was so unnerved by her that he passed her to a colleague to teach.

Elisabeth met Heinrich von Herzogenberg in 1865, and they married the following year. After she was married, Brahms grew less afraid of her and felt freer to befriend her and her husband properly.

The couple moved to Graz before settling in Leipzig in 1872 and then Berlin in 1885. Heinrich taught music; Elisabeth maintained a cheerful household and charming correspondence; and both played piano and composed. Here are some of her pieces:

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: 8 Clavierstücke

To their devastation, they were unable to have children, so their musical friends became their family. Brahms became an especially treasured friend.

He was deeply impressed by Elisabeth’s musical opinion and began sending her work to get her feedback. “You should know and believe that you are among the few persons whom one holds so dear that one cannot tell them so,” he wrote to her.

The couple’s health was not great, and in 1891, they went to the Italian town of Sanremo, where Elisabeth died in 1892 when she was just forty-four years old.

Brahms wrote to her grief-stricken husband: “It is vain to attempt any expression of the feelings that absorb me so completely. You know how unutterably I myself suffer from the loss of your beloved wife and can gauge accordingly my emotions in thinking of you, who were associated with her by the closest possible human ties.”

He dedicated his Rhapsodies, op. 79 to her.

The 5 Hottest Etudes by Scriabin

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

Alexander Scriabin

By blending elements of mysticism, spirituality, and even philosophy, Scriabin developed a highly personal chromatic style that was both erotically expressive and grandiose. Sadly, his life was tragically short, but his bold and visionary style left a lasting mark on the world of classical music that inspired generations of composers and listeners alike.

To celebrate his birthday, we’ve decided to feature some of his most celebrated works, the Études for piano. These works are such a fascinating blend of technical virtuosity and deep emotional expression. The early etudes are lush and Romantic pieces, full of lyrical beauty and sweeping arpeggios, while his later works shift to a more dissonant, mystically charged style. One thing for sure, Scriabin pushes both the technical and expressive limits of the piano, creating pieces that are as challenging as they are evocative. Are you ready for the 5 hottest Etudes by Scriabin?

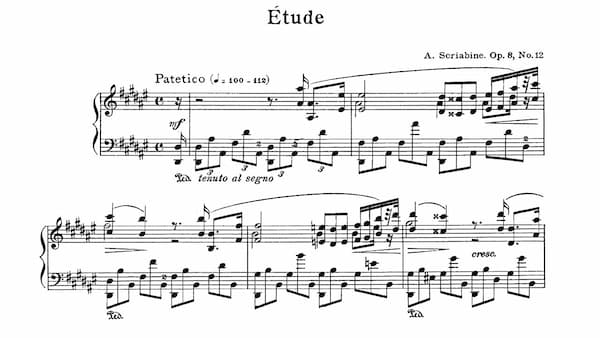

Étude in D-sharp minor, Op. 8, No. 12

I think it’s fair to start this blog on the 5 hottest etudes with the best-known piano composition by Scriabin. The Étude in D-sharp minor, Op. 8, No. 12 is one of his most dramatic and technically demanding works. Deeply influenced by Chopin, Scriabin’s etudes are much more than just technical exercises, they are fully developed concert pieces. The harmonic language is already highly chromatic, with frequent modulations that avoid clear resolutions.

Alexander Scriabin’s Etude Op. 8 No. 12 music score excerpt

Some pianists describe Op. 8 No. 12 as “ostensibly an octave study,” but I am more interested in the emotional intensity of the piece. The surging, restless rhythms and constantly shifting harmonies create a sense of unease and urgency, while the lyrical moments in the second theme introduce a contrast of yearning and melancholia. The explosive outbursts in the coda describe the emotional apex, and the tension is finally released in a frenzied flurry of notes.

The unresolved ending, which abruptly cuts off after the tumultuous build-up, leaves a lingering sense of ambiguity and unfinished business. This seems very characteristic of Scriabin’s early works, where he often leaves the listener in a state of emotional suspension.

Étude in C-sharp minor, Op. 2 No. 1

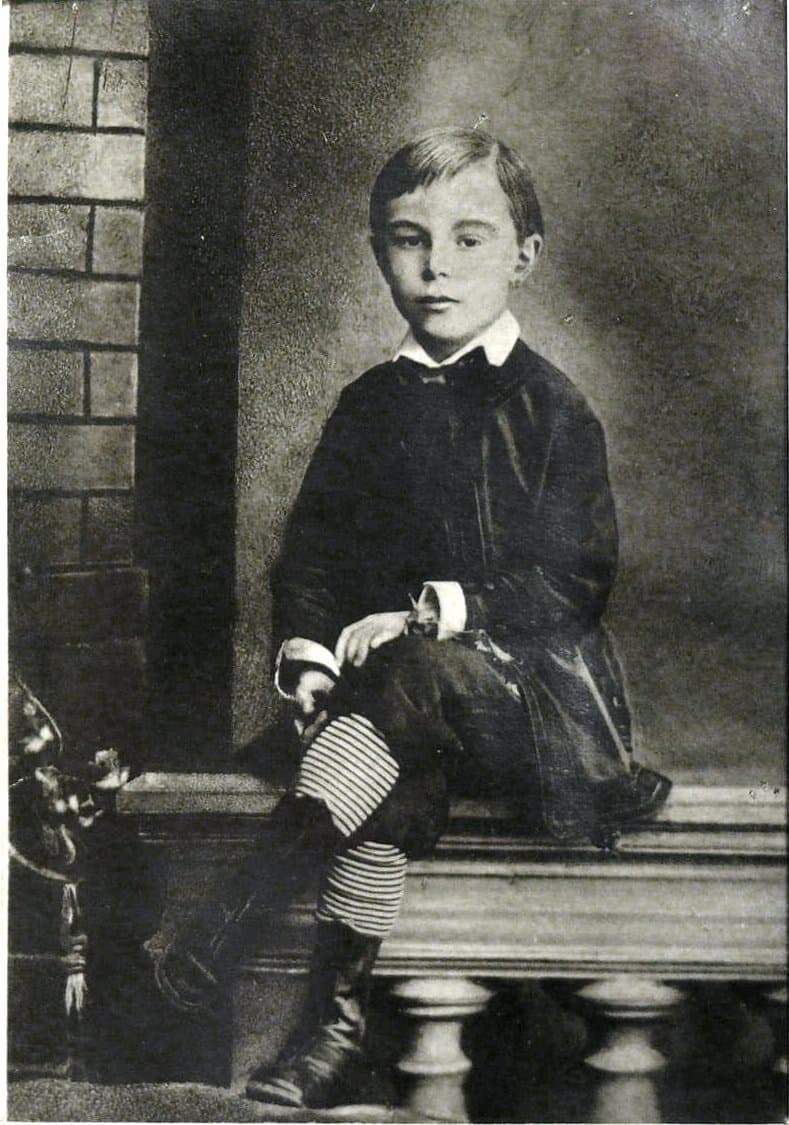

Scriabin was only 14 years old when he wrote his Étude Op. 2 No. 1. An astonishingly mature composition for a teenager, this etude is a study in tonal balance, pedalling and cantabile chord playing. Long arching phrases and passionate melancholy are reminiscent of Rachmaninoff, and they offer pianists the opportunity to showcase passion, intensity, and lyrical beauty. As is the case in all Scriabin etudes, the contrasting sections create a journey through emotional extremes, requiring the performer to balance technical brilliance with expressive depth.

The young Alexander Scriabin

This teenage work already shows glimpses of Scriabin’s genius as it contains the seeds of what would become Scriabin’s hallmark style. And that is an intricate balance between dramatic intensity, harmonic experimentation, and lyrical beauty. In terms of harmony, we hear a rich chromaticism and exotic harmonies like the “French sixth,” a chord with profound anti-tonal implications consisting of two interlocking tritones.

For me personally, Op. 2 No. 1 is a miracle as it exposes a vast emotional range, moving from conflict and passion to yearning and introspection. And just listen to the aching sense of restlessness throughout; this is one of the hottest Scriabin etudes for sure.

Étude in B Major, Op. 8 No. 4

The Scriabin Op. 8 blends lyrical expression with technical brilliance. Composed in 1894, I very much love Op. 8 No. 4 because of its intense lyricism, its shimmering harmonies, and the delicious tension between lightness and intensity. Scriabin once again uses extended harmonies to evoke a sense of depth and complexity, and chromatic modulations dart between related and distant keys.

This most lyrical and expressive etude is like an emotional journey that contrasts melancholy and exuberance. In the opening, the pianist explores subtle phrasing to bring out the song-like quality in the right hand. In the middle section, however, the mood shifts to a stormy and dramatic expression with rapid passages creating a sense of turbulence and the shifting harmonies enhancing a feeling of uncertainty and struggle.

What a beautiful work, demanding a delicate balance between lyrical beauty and emotional drama. Technical challenges aside, the best pianists are capable of expressing complex emotional nuances, with the opening theme returning to allow for a satisfying resolution.

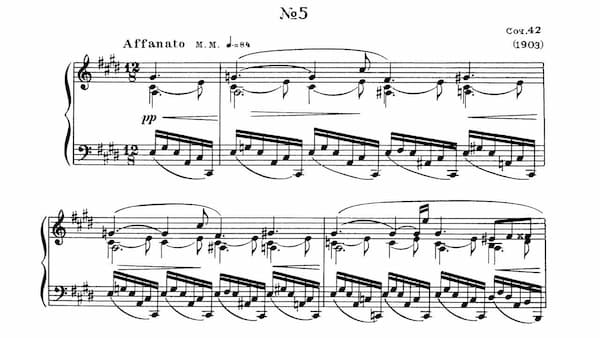

Étude in C-sharp minor, Op. 42 No. 5

It is frequently pointed out that Scriabin’s twenty-six etudes for solo piano reflect different stages of his composing career. We have already seen how his earliest etudes are very similar in style to the works of Chopin. By 1903, however, Scriabin’s life became somewhat tumultuous. He resigned his teaching position from the Moscow Conservatory, divorced his first wife, and began a relationship with his former student, Tatyana Schloezer. He also started work on an opera and used the title of “poem” regularly in his work.

His etudes Op. 42 are said to be stimulated by Scriabin’s relationship with Schloezer, and the strong lyricism and emotional power of the melodies suggest the influence of vocal writing from his opera. But in this set, Scriabin is exploring his own unique tonality, noticeably the extended use of tritones. And let’s not forget those amazing cross-rhythms, melodic lines, and bittersweet and intense qualities.

Alexander Scriabin’s Etude Op. 42 No. 5 music score excerpt

The most famous etude in this set is the overpowering 5th etude in C-sharp minor. I just love the description of George Ledin, who writes, “Here Scriabin’s canvas is galactic, and his strokes are colossal. The cosmic ship is buffeted by giant breakers, waves that boom and bellow with primal authority. The ship’s journey is rebellious and daring, yet its destiny and destination are uncertain.”

Étude in F-sharp Major, Op. 42 No. 4 (Vadym Kholodenko, piano)

Let’s stay with the Op. 42 set, specifically the F-sharp Major etude No. 4. It is one of the hottest pieces in this set, showcasing a distinctive compositional style and a transition into a more complex and expressive harmonic language. It certainly demands both a virtuosic technique and an advanced understanding of musical expression, particularly in terms of colour, phrasing, and dynamic control.

Once again, the rich harmonies are rapidly shifting, and Scriabin uses plenty of diminished and augmented chords. The use of non-functional harmonies is typical of Scriabin’s style during this period. It all provides a sense of harmonic instability, contributing to its emotional depth and a sense of tension.

This etude is a showcase for the careful use of rubato and flexible phrasing, particularly in the lyrical passages. There is always a sense of urgency, but everything is garnished with moments of delicate introspection.

3 Étude Op. 65

Helena Blavatsky

As a bonus, I have to briefly feature the set of 3 Etudes Op. 65. These pieces date from 1911-12 and are the final stage of his composing career. This set of etudes is the result of his discovery of a new spiritual realm in the person of Helena Blavatsky, a founding member of the theosophic society. This society was looking to find hidden knowledge or wisdom in all faiths, philosophies and cults and offered individual enlightenment and salvation.

For Scriabin, this new spiritual realm coincided with a new direction in music. He created his own surreal universe where time and space seemingly disappear, and his music becomes filled with colour, perfume, fantasy, dance, and illusion. For sure, the etudes Op. 65 carry a cosmic or celestial feel with ascending runs leading to a higher register and to his signature “celestial” textures.

A scholar writes, “Scriabin’s eccentric personality and self-promoting tendencies have led to his music being undervalued by many, and his works are often dismissed due to his reputation.” For me personally, they are wonderful miniatures of great technical difficulties that provide an entry into an often neglected musical world.

Heavenly Soundscapes: The Church Sonatas of Mozart

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13 in Verona, 1770

As we celebrate Mozart’s birthday on 27 January, we decided to showcase masterpieces of a very special kind. And I am talking about his church sonatas, sometimes also known as the “Epistle Sonatas.” Mozart wrote 17 of these short works, musical gems of concentration on the small form. As the composer himself said, “you need a special kind of training for this kind of composition.”

Forgotten Gems

Don’t feel bad if you are not familiar with these charming miniatures. These works were part of the religious service at the cathedral in Salzburg, written for a very specific function. Today, they no longer have that particular function in the liturgy of the Catholic mass, and they certainly have no fixed place in the concert repertoire. The church sonatas by Mozart have led a life in the shadow; it’s high time to bring them into the light!

Official Church Musician

Salzburg Cathedral

The church sonatas date from a time when Mozart served at the court in Salzburg in an official capacity for 10 years. Initially he was hired as an unsalaried “concert master “on 27 October 1769, but was officially on the payroll in this particular position from August 1772 to August 1777. He was then promoted to “cathedral and court organist,” with a salary of 450 guilders in January 1779. This position would be terminated by the famous “swift kick to the backside” in May 1781.

Archbishop Colloredo

Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo

Mozart had a famously turbulent relationship with his boss, Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo. Colloredo was in charge for much of the 1770s and early 1780s, but their dynamic was strained from the start. Mozart, known for his independent spirit and desire for creative freedom, was at odds with the archbishop, who was more interested in maintaining control and adhering to formalities. The tension escalated as Mozart resented the rigid, often patronising treatment he received, especially when Colloredo limited his opportunities to compose freely and perform outside Salzburg.

Liturgical Function

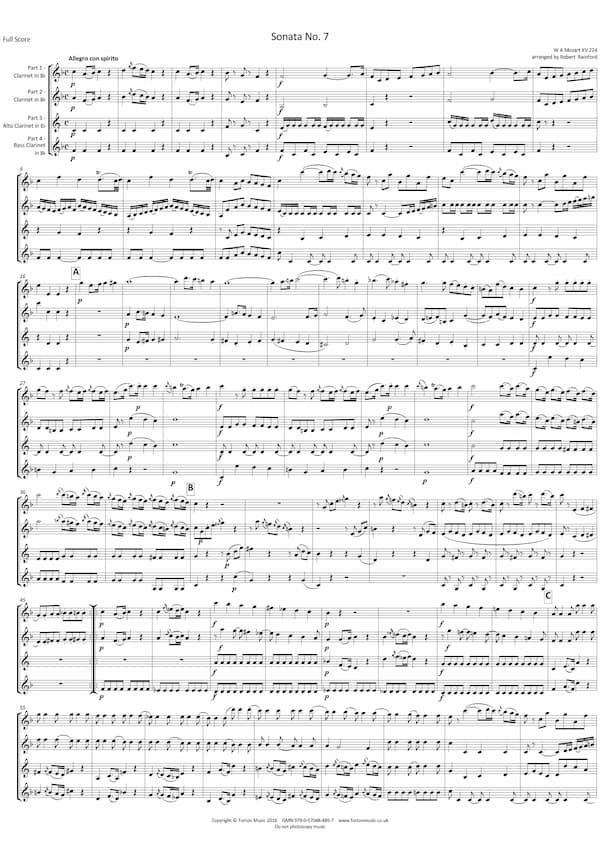

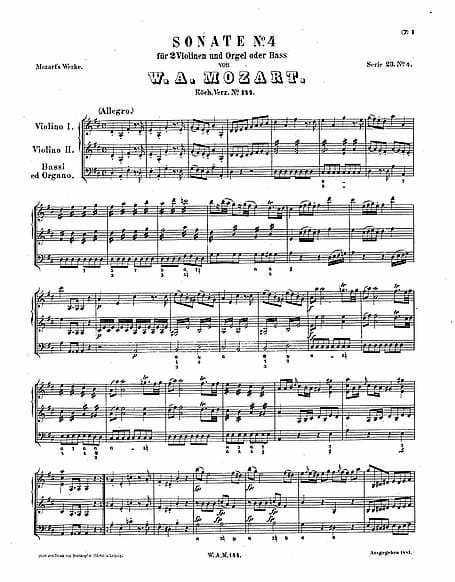

Mozart’s Church Sonata No. 7 in F Major, K. 224 music score excerpt

So, what was the specific liturgical function of Mozart’s church sonatas? We get the answer from a Mozart letter to Padre Martini from September 1776. Mozart wrote in Italian, “our church music is very different from that of Italy, since a mass with the whole Kyrie, the Gloria, the Credo, the Epistle Sonata, the Offertory or Motet, the Sanctus and the Agnus Dei, even the most solemn one, may not last more than a maximum of three-quarters of an hour when the Prince attends it; and yet it must be a mass with all instruments, war trumpets and timpani.”

Epistle Sonata

From Mozart’s letter, we learn about the position of the “Epistle Sonata” in the liturgy, but it’s still not straightforward. One scholar wrote the following explanatory footnote to Mozart’s letter. “While the priest reads the Epistle, the organist played softly a sonata with or without violin accompaniment.” We do know that this type of musical composition probably originated in northern Italian churches in the 17th century and subsequently made their way into Austria.

Solemn Occasion

I can’t believe that Archbishop Colloredo would have tolerated any kind of music to interrupt the reading of the Epistle. It is much more likely that these short instrumental works sounded between the reading of the Epistle and the Gospel as the priest solemnly walked from the southern part of the church to the Nave.

Musician Placement

Now that we know when the Epistle Sonatas would have been performed within the liturgy, we still don’t know where the musicians would have been placed inside the church. Presumably, the position would have been close to the various organs in the Salzburg Cathedral, and we are fortunate to have an exact account of the number and dispositions of the organs from Leopold Mozart.

Organs of the Cathedral

Salzburg Cathedral main organ

Leopold writes, “In the Archiepiscopal Cathedral, the large organ is placed at the back near the entrance of the church; nearer the front, at the choir, there are four auxiliary organs, and below, in the choir itself, there is a small choir-organ about with the singers are placed. During an elaborate service, the large organ is used only for playing the prelude; for the remainder of the service, however, one of the four auxiliary organs is constantly employed, particularly the one nearest the right side of the altar, where the solo singers and basses are stationed.”

Large Forces

Mozart’s Church Sonata No. 4 in D Major, K. 144 music score excerpt

Leopold continues, “opposite, at the left auxiliary organ, are the violinists, etc., and the two groups of trumpets and kettledrums are near the remaining auxiliary organs. The lower choir organ and violins join in at fully scored passages. The oboes and flutes are seldom heard in the Cathedral, and the horn never. All these players are able to play violins if necessary. The full number of persons connected with music, or who receive pay for musical service at the court, is ninety-nine.”

Mozart the Organist

Since every epistle sonata features the organ in one way or another, maybe we also have to look at Mozart’s relationship with that instrument. He held an immense appreciation for the organ, and in a letter to his father in 1777, he wrote, “In my eyes and ears, the organ is the king of instruments.” However, Mozart composed virtually no works for the organ, aside from a few fugues or fragments of fugues.

Mozart the Improvisor

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart © media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com

However, when it came to playing the organ, Mozart was an undisputed master. The composer Carl Czerny reported that Mozart was able to play the organ with great virtuosity and could improvise intricate music on the spot. That impression is confirmed by Johann Friedrich Doles, Kantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. After hearing Mozart improvise, he wrote, “I was enchanted by his playing and thought that my teacher, old Sebastian Bach, had been reborn.”

The 17 Church Sonatas

Mozart composed a total of 17 Church Sonatas during his tenure at Salzburg Cathedral. They correspond, as Martin Haselböck has observed, with the seventeen instrumental masses composed by Mozart. Scored predominantly for strings and organ, which function either as a solo instrument or as continuo, these works display Mozart’s genius for melody, form, and instrumentation. The first three sonatas, K. 67-69 were possibly written when Mozart was only about eleven years old.

Early Efforts

The actual date of Mozart’s earliest church sonatas is uncertain, but together with K. 144 and 145, they were probably written in the first year of Mozart’s appointment at the cathedral. As you can tell, they are really very short and probably exactly what the Archbishop wanted. As a general observation, the 17 Sonatas are written in 7 keys. Although they are all in major, Mozart does include some striking modulations into the minor key. In Mozart’s hand, as we well know, two bars of minor harmonies can say more than an entire symphony elsewhere.

Central Group

The sonatas in the group ranging from K. 212 to K. 278 originate between 1775 and 1777 and were written for the same ensemble as the first five, for two violins, cello, organ, and bass. There are only two exceptions, K. 263 added a pair of trumpets, and K. 278 featured trumpets, timpani, and a pair of oboes as it was a festive piece written for Easter Sunday in 1777.

Delicious Variety

Let us briefly look at two specific examples, first the sonata K. 244, dating from April 1776. Delicately structured and emphasising a light musical texture, this Sonata opens with a stately and invigorating yet charming musical theme. Independently contributing to the musical discourse, the organ plays a separate concertante part, clearly audible in the slightly subdued thematic contrast.

Composed in 1777, the sonata K. 274 begins with a sprightly unison passage that quickly gives way to an energetic theme. A subtle modulation gradually directs the music towards a delicate dialogue between the instruments before the opening section is repeated.

Final Efforts

The last three church sonatas, K. 328, 329, and 336, have a much more important organ part. Since Mozart would have been playing the organ, he made sure that he would have something interesting to do. K. 328 immediately displays a festive character, one that is not necessarily bound to its sacred function. Operatic in character and symphonic in its overall formal and musical structure, the independent organ part once more enriches the musical texture and provides colourful timbral contrasts.

In fact, K. 336 follows the character and convention of an instrumental concerto. Introduced in the strings, the thematic material is immediately taken over by the organ and thoroughly embellished. This miniature concerto even includes a dedicated cadenza, in which the organist performs an elaborate and virtuosic improvisation.

Stylistically, the works written during the course of one decade mirror the rapid development of Mozart the composer. While the spirit of the Italian opera pervades the early compositions, “the polyphonic structure is increasingly interrupted in favour of a symphonic development.” The great movements “correspond to the symphonic and concertante pieces written around the same time in both their construction and thematic work.”

As Gerald Larner writes, “Mozart gradually asserted his authority from K. 224 onwards, enriching both the texture and the construction, adding harmonic and colour interest, and finally achieved mastery of a peculiar Salzburg form by expanding its limitation.” I am pretty sure that Mozart managed to irritate the impatient Archbishop! While these sonatas are not as widely known as some of Mozart’s other works, they are certainly impressive in their depth and spiritual expressiveness. Happy Birthday!