by Hermione Lai, Interlude

Alexander Scriabin

By blending elements of mysticism, spirituality, and even philosophy, Scriabin developed a highly personal chromatic style that was both erotically expressive and grandiose. Sadly, his life was tragically short, but his bold and visionary style left a lasting mark on the world of classical music that inspired generations of composers and listeners alike.

To celebrate his birthday, we’ve decided to feature some of his most celebrated works, the Études for piano. These works are such a fascinating blend of technical virtuosity and deep emotional expression. The early etudes are lush and Romantic pieces, full of lyrical beauty and sweeping arpeggios, while his later works shift to a more dissonant, mystically charged style. One thing for sure, Scriabin pushes both the technical and expressive limits of the piano, creating pieces that are as challenging as they are evocative. Are you ready for the 5 hottest Etudes by Scriabin?

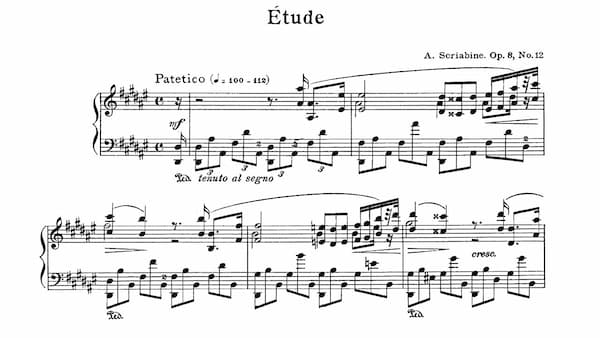

Étude in D-sharp minor, Op. 8, No. 12

I think it’s fair to start this blog on the 5 hottest etudes with the best-known piano composition by Scriabin. The Étude in D-sharp minor, Op. 8, No. 12 is one of his most dramatic and technically demanding works. Deeply influenced by Chopin, Scriabin’s etudes are much more than just technical exercises, they are fully developed concert pieces. The harmonic language is already highly chromatic, with frequent modulations that avoid clear resolutions.

Alexander Scriabin’s Etude Op. 8 No. 12 music score excerpt

Some pianists describe Op. 8 No. 12 as “ostensibly an octave study,” but I am more interested in the emotional intensity of the piece. The surging, restless rhythms and constantly shifting harmonies create a sense of unease and urgency, while the lyrical moments in the second theme introduce a contrast of yearning and melancholia. The explosive outbursts in the coda describe the emotional apex, and the tension is finally released in a frenzied flurry of notes.

The unresolved ending, which abruptly cuts off after the tumultuous build-up, leaves a lingering sense of ambiguity and unfinished business. This seems very characteristic of Scriabin’s early works, where he often leaves the listener in a state of emotional suspension.

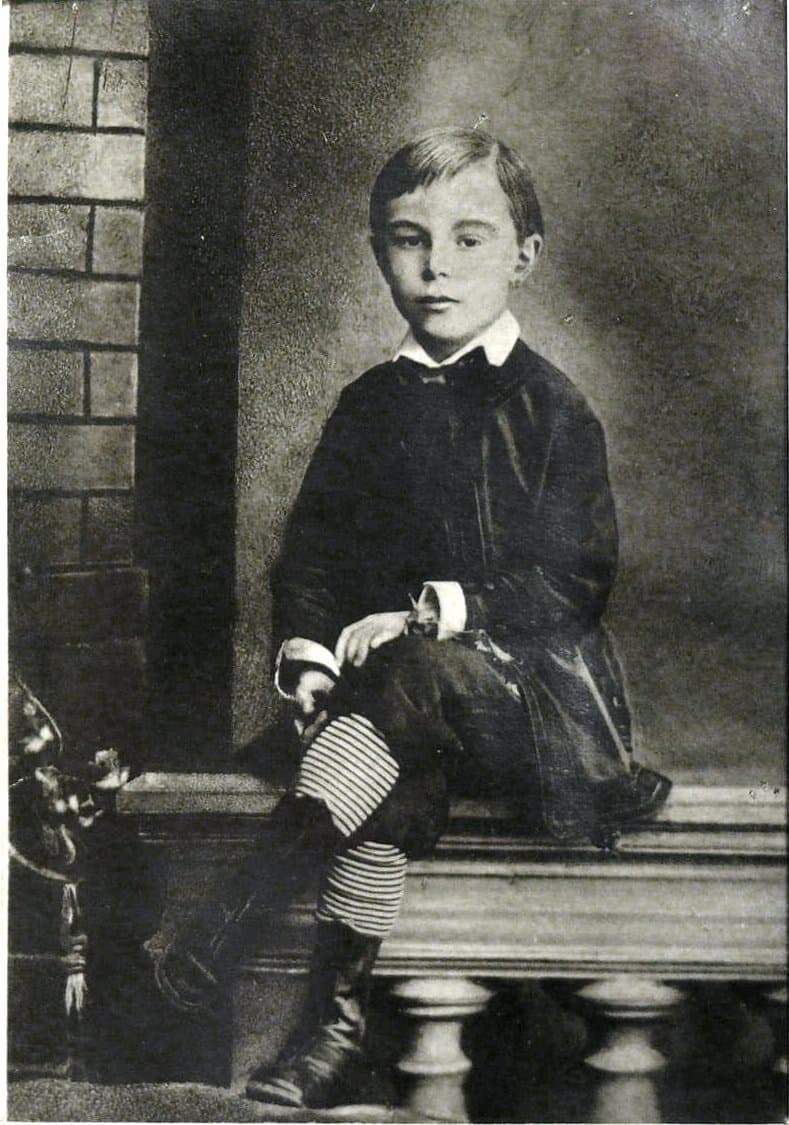

Étude in C-sharp minor, Op. 2 No. 1

Scriabin was only 14 years old when he wrote his Étude Op. 2 No. 1. An astonishingly mature composition for a teenager, this etude is a study in tonal balance, pedalling and cantabile chord playing. Long arching phrases and passionate melancholy are reminiscent of Rachmaninoff, and they offer pianists the opportunity to showcase passion, intensity, and lyrical beauty. As is the case in all Scriabin etudes, the contrasting sections create a journey through emotional extremes, requiring the performer to balance technical brilliance with expressive depth.

The young Alexander Scriabin

This teenage work already shows glimpses of Scriabin’s genius as it contains the seeds of what would become Scriabin’s hallmark style. And that is an intricate balance between dramatic intensity, harmonic experimentation, and lyrical beauty. In terms of harmony, we hear a rich chromaticism and exotic harmonies like the “French sixth,” a chord with profound anti-tonal implications consisting of two interlocking tritones.

For me personally, Op. 2 No. 1 is a miracle as it exposes a vast emotional range, moving from conflict and passion to yearning and introspection. And just listen to the aching sense of restlessness throughout; this is one of the hottest Scriabin etudes for sure.

Étude in B Major, Op. 8 No. 4

The Scriabin Op. 8 blends lyrical expression with technical brilliance. Composed in 1894, I very much love Op. 8 No. 4 because of its intense lyricism, its shimmering harmonies, and the delicious tension between lightness and intensity. Scriabin once again uses extended harmonies to evoke a sense of depth and complexity, and chromatic modulations dart between related and distant keys.

This most lyrical and expressive etude is like an emotional journey that contrasts melancholy and exuberance. In the opening, the pianist explores subtle phrasing to bring out the song-like quality in the right hand. In the middle section, however, the mood shifts to a stormy and dramatic expression with rapid passages creating a sense of turbulence and the shifting harmonies enhancing a feeling of uncertainty and struggle.

What a beautiful work, demanding a delicate balance between lyrical beauty and emotional drama. Technical challenges aside, the best pianists are capable of expressing complex emotional nuances, with the opening theme returning to allow for a satisfying resolution.

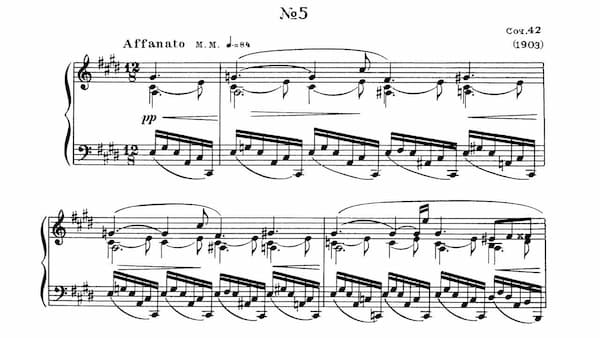

Étude in C-sharp minor, Op. 42 No. 5

It is frequently pointed out that Scriabin’s twenty-six etudes for solo piano reflect different stages of his composing career. We have already seen how his earliest etudes are very similar in style to the works of Chopin. By 1903, however, Scriabin’s life became somewhat tumultuous. He resigned his teaching position from the Moscow Conservatory, divorced his first wife, and began a relationship with his former student, Tatyana Schloezer. He also started work on an opera and used the title of “poem” regularly in his work.

His etudes Op. 42 are said to be stimulated by Scriabin’s relationship with Schloezer, and the strong lyricism and emotional power of the melodies suggest the influence of vocal writing from his opera. But in this set, Scriabin is exploring his own unique tonality, noticeably the extended use of tritones. And let’s not forget those amazing cross-rhythms, melodic lines, and bittersweet and intense qualities.

Alexander Scriabin’s Etude Op. 42 No. 5 music score excerpt

The most famous etude in this set is the overpowering 5th etude in C-sharp minor. I just love the description of George Ledin, who writes, “Here Scriabin’s canvas is galactic, and his strokes are colossal. The cosmic ship is buffeted by giant breakers, waves that boom and bellow with primal authority. The ship’s journey is rebellious and daring, yet its destiny and destination are uncertain.”

Étude in F-sharp Major, Op. 42 No. 4 (Vadym Kholodenko, piano)

Let’s stay with the Op. 42 set, specifically the F-sharp Major etude No. 4. It is one of the hottest pieces in this set, showcasing a distinctive compositional style and a transition into a more complex and expressive harmonic language. It certainly demands both a virtuosic technique and an advanced understanding of musical expression, particularly in terms of colour, phrasing, and dynamic control.

Once again, the rich harmonies are rapidly shifting, and Scriabin uses plenty of diminished and augmented chords. The use of non-functional harmonies is typical of Scriabin’s style during this period. It all provides a sense of harmonic instability, contributing to its emotional depth and a sense of tension.

This etude is a showcase for the careful use of rubato and flexible phrasing, particularly in the lyrical passages. There is always a sense of urgency, but everything is garnished with moments of delicate introspection.

3 Étude Op. 65

Helena Blavatsky

As a bonus, I have to briefly feature the set of 3 Etudes Op. 65. These pieces date from 1911-12 and are the final stage of his composing career. This set of etudes is the result of his discovery of a new spiritual realm in the person of Helena Blavatsky, a founding member of the theosophic society. This society was looking to find hidden knowledge or wisdom in all faiths, philosophies and cults and offered individual enlightenment and salvation.

For Scriabin, this new spiritual realm coincided with a new direction in music. He created his own surreal universe where time and space seemingly disappear, and his music becomes filled with colour, perfume, fantasy, dance, and illusion. For sure, the etudes Op. 65 carry a cosmic or celestial feel with ascending runs leading to a higher register and to his signature “celestial” textures.

A scholar writes, “Scriabin’s eccentric personality and self-promoting tendencies have led to his music being undervalued by many, and his works are often dismissed due to his reputation.” For me personally, they are wonderful miniatures of great technical difficulties that provide an entry into an often neglected musical world.