It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, December 14, 2024

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E‑flat Major "Emperor"

Nostalgic Noel: The Coziest Christmas Carols - The Maestro & The European Pop Orchestra

Friday, December 13, 2024

When Simple is Necessary: Fauré’s Berceuse

by Maureen Buja

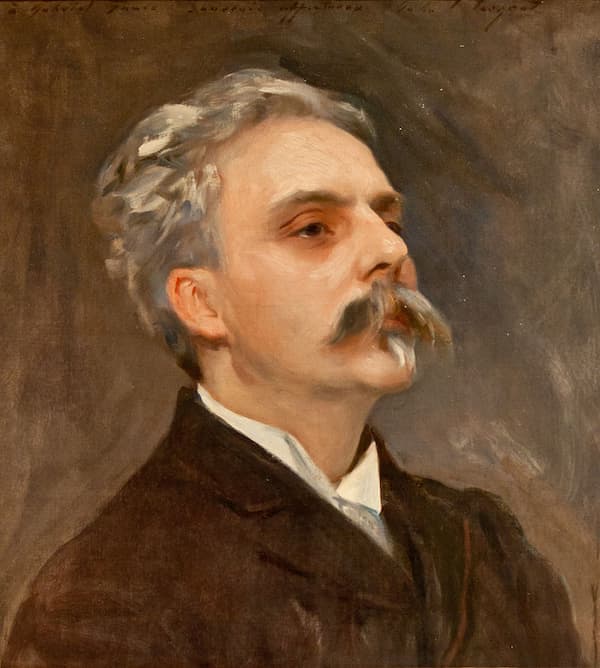

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1899 (Paris: Musée de la Musique)

Fauré made his name at two major French churches as an organist. First at the Église Saint-Sulpice, where he started as the choirmaster in 1871 under the organist Chares-Marie Widor before moving to the Église de la Madeleine in 1874, where he was deputy organist under Camille Saint-Saëns, taking over when the senior organist was on one of his frequent tours. Although he was recognised as a leading organist and played it professionally for some 40 years, he didn’t appreciate its size, with one commentator saying, ‘for a composer of such delicacy of nuance, and such sensuality, the organ was simply not subtle enough’.

In 1879, he wrote a little Berceuse that was quickly appreciated by violinists. Fauré himself didn’t quite see what the fuss was about, but the work went into the repertoire of many violinists in the late 19th century and was recorded by the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe.

The premiere of the work was given in February 1880 at the Société Nationale de Musique (which Fauré was a founding member) with the violinist Ovide Musin and the composer at the piano. The French publisher Julien Hamelle was at the performance and quickly put the work into print, where it sold over 700 copies in its first year alone.

It has been arranged for cello, violin and orchestra, and even as a vocalise for text-less voice and harp.

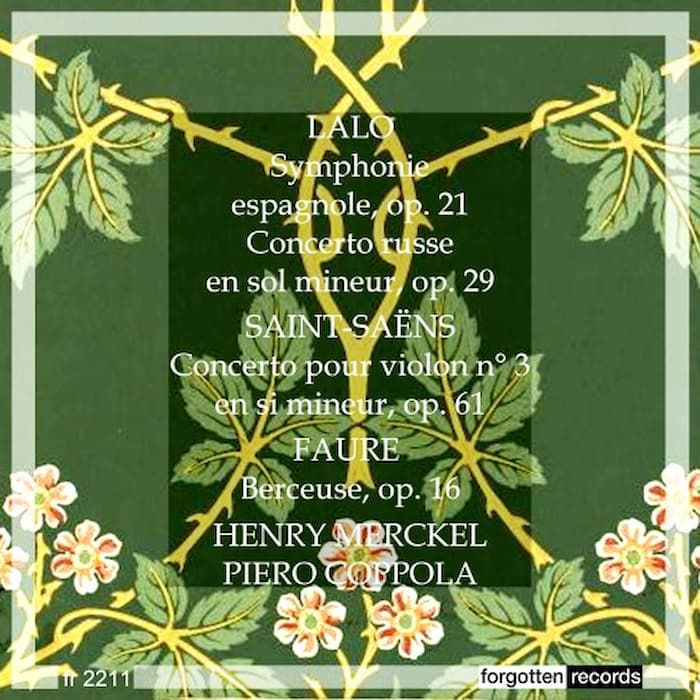

This recording was made in 1935, with violinist Henry Merckel, under Piero Coppola leading the Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup.

Henry Merckel

Henry Merckel (1887–1969) was a classical violinist from Belgium who graduated from the Paris Conservatoire in 1912. He had his own string quartet and was concertmaster of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra (now known as the Orchestra de Paris) from 1929 to 1934, and also served as concertmaster of the Paris Opera Orchestra from 1930 until 1960.

Piero Coppola

The Italian conductor Piero Coppola (1888–1971) studied piano and composition at the Milan Conservatory. He graduated in 1910 and, in 1911, was already conducting at La Scala. He is known for his recordings of Debussy and Ravel in the 1920s and 1930s, including the first recordings of Debussy’s La Mer and Ravel’s Boléro, with his Debussy recordings being praised as ‘close to Debussy’s thoughts’. From 1923 to 1934, he was the artistic director of the recording company La Voix de son Maître, the French branch of The Gramophone Company, under whose name this recording was made.

The Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup, founded in 1861 by Jules Pasdeloup, is the oldest symphony orchestra in France. They scheduled their concerts for Sundays to catch concert-goers who weren’t able to make evening concerts. It started out with the name of Concerts Populaires and ran until 1884. It was started up again in 1919 under Serge Sandberg as the Orchestre Pasdeloup.

Performed by

Henry Merckel

Piero Coppola

Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup

Recorded in 1935

César Franck (1822-1890): A Birthday Tribute

by Hermione Lai

César was a child genius who loved drawing and playing the piano. His father spotted these talents early and decided to market his young son as a piano prodigy. We come across irresponsible and ambitious parents in the arts all the time, but Nicholas-Joseph was especially aggressive.

The young César Franck

He took his son from one concert tour to the next and made him enrol at the Conservatoire, only to withdraw him from his studies for lengthy concert tours. Much later in life, César confided in his diary, “my father had grand ideas of money flowing like a river towards us, but unfortunately, it was not so.”

The press took strong exception to the highly aggressive promotional efforts of his father, and only at the age of 24 did César Franck walk out of his parent’s house, making a clear break. But life wasn’t easy as his compositions received only mixed reactions and were not embraced by the public. On the anniversary of his birth on 10 December, we decided to pay tribute to this marvellous composer who played an important role in French music.

Violin Sonata in A major,

Let’s get started with Franck’s most famous work, the Violin Sonata in A major. Written in 1886, it is like a musical rollercoaster, full of twists and turns. It is a vibrant and passionate piece that is already a favourite for violinists and audiences. Actually, it’s considered a cornerstone of the violin repertoire and is cherished for its rich thematic material and emotional depth.

One can easily hear Franck’s famous “cyclic structure,” which just means that themes reappear in different movements. This creates a wonderful sense of unity throughout the piece. The opening theme sweeps you into a world of deep emotions, but just when you think it’s getting serious, the music lightens up and dances through playful, joyful passages.

César Franck’s Violin Sonata

The way the violin and piano work together is like a conversation, with each instrument taking turns to lead, complement, and surprise the other. With its lush harmonies and soaring melodies, the sonata has this magical ability to move you, making you feel like you’re on an exciting adventure through sound. This piece is a true gem of the late Romantic period, brimming with passion, warmth, and joy.

Symphony in D minor

Initially, nobody much liked Franck’s D-minor symphony. It was first performed in 1889 with critics unsure about its place in the symphonic tradition. Some found the work bold and thrilling, while others were critical of the harmonic language and the overall structure. It was just too unconventional for its time. Times have changed, however, and today, it is considered one of Franck’s greatest masterpieces, full of emotional power and depth.

The music is like a thrilling, whirlwind musical journey. It’s packed with rich and sweeping themes and plenty of dramatic contrasts. The more I listen to it, the more it feels almost cinematic. There is bold and fiery energy from the very beginning, and just listen to these almost heroic declarations in the interaction between strings and brass. But it’s not all drama, as the second movement offers lush and lyrical melodies in a quiet conversation between the string and woodwinds.

The third movement is a bit of a surprise, as it is almost mischievous at times. It seems full of life and certainly puts a smile on your face. In the finale, Franck pulls out all the stops. He takes all the themes and musical ideas that have been bubbling throughout the piece and brings them together in a thrilling and triumphant conclusion. It is a masterpiece containing intense drama, moments of reflection, and pure moments of joy.

Trois Pièces for Organ

Organ of Sainte-Clotilde, Paris

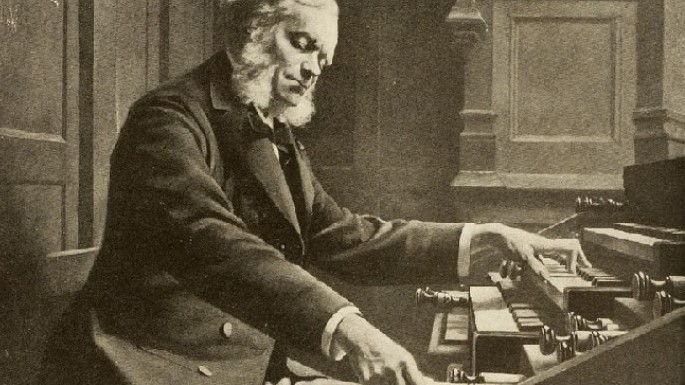

Franck had always aspired to become an organist, and when he was appointed at the church of Sainte-Clotilde, his dream became a reality. As he later explained, “if you only knew how I love this instrument. It is so supple beneath my fingers and so obedient to all my thoughts.” His improvisations became legendary, and his organ compositions stand at the apex of the Romantic organ repertoire.

Franck’s Three Pieces for Organ are like musical gems, each with its own distinct character, but all combining the composer’s genius for combining passion, drama, and tenderness. Composed in 1878, these pieces are full of vivid contrasts and stunning harmonic colours, almost like sweeping landscapes painted with sound.

The “Fantaisie” transports us into a grand cathedral with organ pipes resonating through the space. Expansive chords and soaring themes offer a diverse musical flow, with moments of turbulent energy followed by calm reflections. The powerful sound of the organ takes centre stage in the “Pièce Héroïque.” It is majestic and commanding, full of energy, and almost like a call to arms. But even within this intensity, there are tender moments that add layers of emotional depth. The “Cantabile” returns to a more intimate and serene space. It is the heart of the set, a gentle and lyrical work that contrasts with the fiery drama of the previous movements.

Prelude, Fugue, and Variation

As I wrote in the introduction, Franck was an exceptional pianist. For a time, he seemed to be in competition with Franz Liszt. They personally met on a couple of occasions, and Liszt later wrote to a friend. “He will find the road steeper and rockier than others may, for, as I have told you, he made the fundamental error of being christened César-Auguste, and, in addition, I fancy he is lacking in that convenient social sense that opens all doors before him.”

Clearly, Franck was never comfortable under the glaring light of the virtuoso stage, and to prove that point, he composed the “Prelude, Fugue, and Variation” in 1884. Franck was at the height of his maturity as a composer, and this beautiful and intricate work, initially for organ but later arranged for solo piano, reflects Franck’s rich harmonic language and his deep understanding of counterpoint. It’s basically a homage to Bach, and each section offers a different way of approaching the initial theme.

Franck introduces us to a beautifully simple theme that is immediately inviting and conversational. The real fun begins in the “Fugue” when Franck stretches out the theme, and each new entry of the theme adds its own twist. He also incorporates surprising harmonic turns or playful rhythms, with each voice giving a new level of depth to the original theme. In the “Variation”, he dresses the theme in different costumes, with each variation showing a new side of its character. He certainly is having fun exploring all the possibilities of what the theme has to offer.

The Cursed Hunter

Pierre Petit: César Franck

I just love a good story translated into music. And that is exactly what Franck did in 1883 when he composed “The Cursed Hunter.” It tells the story of the count of the Rhineland who commits the sacrilege of going hunting on a Sunday. He happily ignores the sound of the bells and the singing of the faithful on their way to Mass. But very soon, his horse stopped, and his hunting horn fell silent. A terrifying voice utter a horrendous curse; the huntsman is condemned to ride forever, pursued by demons.

Franck’s symphonic poem, and he composed five such colourful stories in music, is a wild ride through a dark and eerie forest full of dramatic twists and unexpected turns. He brings the legend of the hunter to life with a mix of spooky moments and frantic energy. It all starts with a somewhat mysterious theme, setting the mood for the cursed ride.

The music continues to build, and the orchestra bursts into action with various bold and sweeping melodies that hint at danger. As you might expect from this story, the rhythm is relentless as it mimics the endless chase. Darker and more ominous tones suggest the curse, but finally, it seems that the chase might be over. It all ends in a dramatic and unresolved way, but it is clear that the hunter won’t escape. What a thrilling and atmospheric work, full of suspense and excitement; that’s why I love symphonic poems.

Symphonic Variations

Franck composed his Symphonic Variations for piano and orchestra in 1885. One of Franck’s most approachable compositions, it showcases the composer’s love for harmonic complexity and his mastery of orchestration. However, it also contains moments of deep emotional richness.

The principal theme is introduced by the piano. It is an elegant and simple theme, almost a dreamy melody that is then echoed and explored by the full orchestra. What is really fun about this piece is how Frank takes that theme and spins it into something new and exciting with every variation. He offered different moods, tempos, and textures, alternating between light and playful utterances and bold and dramatic statements.

A real highlight of this work is the interaction between the piano and orchestra, with the theme constantly evolving. It certainly reveals the composer’s deep understanding of both thematic development and orchestral colour. To be sure, Franck uses his gift for blending beauty and drama in a mixture of elegance and compositional genius. It’s a wonderful example of blending tradition with innovation, and it is one of the composer’s most accessible works.

“Nocturne”

The mélodies by César Franck were only known to a small circle of connoisseurs during his lifetime. Today, however, they are recognised for their expressive power and the composer’s ability to merge lyrical melodies with rich and complex harmonies. A scholar wrote, “His contributions to the French mélodie genre helped bridge the gap between the more traditional Romantic style and the more modern, impressionistic approaches that were developing around the turn of the 20th century.”

César Franck at the organ

One of my favourite is “Nocturne,” composed in 1882. It is the setting of a poem by Paul Verlaine and captures the serene and contemplative atmosphere of the night. The gently flowing melody is both lyrical and expressive, with the piano providing a shimmering backdrop. And you can hear how Franck’s chromatic harmonic and shifts of tonality enhance the sense of longing conveyed in Verlaine’s text. What a wonderful mélodie, both tender and sophisticated, as it fuses emotional depth with harmonic complexity.

Panis Angelicus (Angelic Bread)

César Franck’s Panis Angelicus

Stanley Sadie described César Franck as “a man of utmost humility, simplicity, reverence and industry.” We have seen that his reputation rests largely with a few large-scale orchestral and instrumental works of his later years. However, most of his compositions are associated with his employment as an organist, a position he held for over 30 years. Naturally, he composed a vast number of organ compositions, but we also find numerous sacred vocal works.

Among his most celebrated compositions is a musical setting of “Panis Angelius,” a serene piece that feels like a musical prayer. The title refers to the Eucharist, and it was composed in 1872 as part of a larger work. The music perfectly captures a sense of reverence and tranquillity, and the simple melody is surrounded by lush harmonies that give it an almost heavenly quality.

Franck’s setting has been described as invoking a sense of “serene anxiety.” This musical paradox also governs the vocal line, as the soloist performs a melody of angelic lyricism enriched by surprising harmonic inflection and the occasional strain of chromatic intonation.

I hope you enjoyed our little excursion into the musical world of César Franck, a world full of emotional intensity and spirituality. Franck was a wonderful composer whose reputation, especially outside of France, took a little longer to develop. But his influence remains powerful, specifically in organ music and in late-Romantic orchestral and chamber works. Happy Birthday Mr. Franck.

Beethoven the European: The Ninth, Celebrated in Leipzig, Paris, Milan and Vienna

by Georg Predota, Interlude

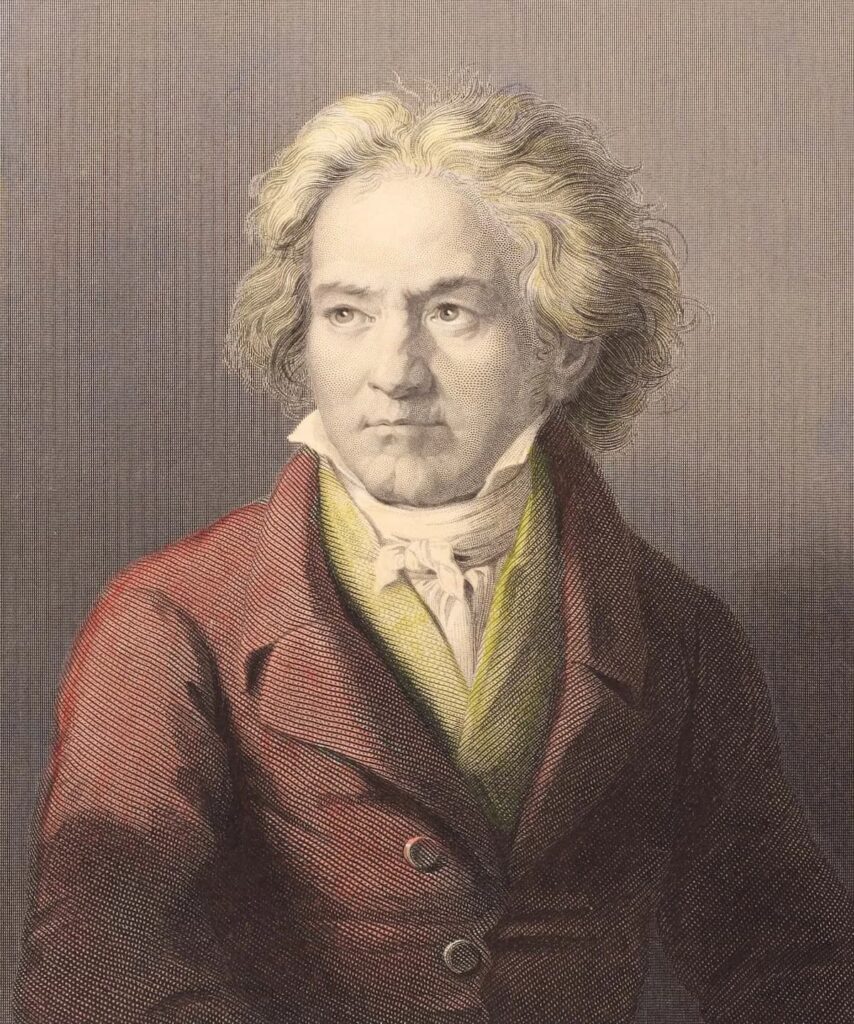

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125

Ludwig van Beethoven was a revolutionary man who lived and worked in tumultuous times as the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars greatly destabilised the European continent. For over two decades of Beethoven’s life, Napoleon was the most powerful man in Europe, an authoritarian who almost succeeded in unifying the continent under French hegemony.

In some works, as Jürgen Thym explains, “Beethoven gave voice to events that were occurring on the political and military level.” The “Bonaparte Symphony,” eventually subtitled “Eroica,” became a celebration of a hero and the musical representation of the ideal of heroic greatness. However, when Beethoven learned that Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor in 1804, he angrily tore up the title page containing the original dedication. And let’s not forget that he gave voice to the demise of the dictator in his highly popular “Wellington’s Victory.”

Ludwig van Beeethoven

The Human Perspective

Beyond the complex and seemingly incomprehensive enormity of Beethoven’s music, we find a man who was thoroughly human. Much has been written and made about his deafness and its impact on the creative process. It predictably affected his mental health by creating a sense of deep isolation and frustration that informed his interaction with society at large.

Beethoven had a small number of close male friends, and most of the women he admired were happily married, committed to somebody else and usually of higher social standing.

Eternally, in search of “tranquillity and freedom,” he showed utter disdain for discipline and authority and, unable to adopt a submissive attitude, brusquely dismissed the conventions of aristocratic society.

In Beethoven, we discover a fragmented individual who is full of contradictions. He struggled with a severe disability, a failing body, mental instability and an alcohol addiction. Once we add his volatile temperament, unrequited love and dreadful communication and social skills to the thorny mix, it becomes clear that composing and the discipline associated with his art was the personal therapy that confidently anchored the sinking ship.

Defiance

Beethoven’s ear trumpets

By 1814, Beethoven had become profoundly deaf, unable to perform in public, unable to hear music, and unable to talk with friends. This silence, which had slowly enveloped the composer beginning in the late 1790s, halted the enormous productivity of his heroic period and led to four years of almost complete inactivity.

The monumental pieces of his “late period” started to take shape in 1819, and the Ninth Symphony emerged as the result of a commission from the London Philharmonic Society in 1821. Completion of the work was delayed until 1824, and Beethoven actually pondered the possibility of concluding his symphony with an instrumental finale. As William Kindermann explained, “a passionate melody in D minor was eventually used in the A-minor String Quartet Op. 132, as Beethoven opted for an affirmative ending.”

Ode to Joy

By appealing to the spirit of Romanticism and the shared ideals of humanity as expressed in Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” the composer appeared to have made not only a musical point but also issued a decisive cultural statement. As a cultural artefact, Beethoven’s celebration of universal brotherhood has been questioned. However, the utopian ideals expressed are once again highly relevant.

Today, the “Ode to Joy” is the anthem of both the European Union and the Council of Europe. Its described purpose is to “honour shared European values, expressing the ideals of freedom, peace, and unity.” In fact, it has become a trans- and international anthem, “a beacon of hope and community.”

ARTE CONCERT

Beethoven’s “Choral Symphony” first sounded at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna on 7 May 1824. To commemorate the 200th anniversary of this memorable event, ARTE is celebrating Beethoven the European by presenting a special celebration of this work; individual movements are performed in four of the most important concert venues across Europe.

Conductor Andris Nelsons opens the festivities at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, the location of the premiere of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5, also known as the “Emperor Concerto.” The European journey continued in Paris, as the Orchestre de Paris was the first French orchestra to play Beethoven’s symphonies shortly after the composer’s death. For the “Scherzo” movement, the Philharmonie de Paris is in the capable hands of Klaus Mäkelä.

Next, Riccardo Chailly takes us to Milan. He conducts the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala in a performance of the “Adagio e molto cantabile,” a melancholy and pensive, some would say, brooding movement. The crowing conclusion takes place at the Konzerthaus in Vienna, with Petr Popelka conducting the Vienna Symphony with soloists Rachel Willis-Sørensen, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, Andreas Schager, and Christof Fischesser.

Andris Nelsons © Marco Borggreve

Klaus Makela © Marco Borggreve

Riccardo Chailly © riccardochailly.com

Petr Popelka © Susanne Hassler-Smith

Assessment

By artistically realising the potential for freedom and optimism within all of us, Beethoven’s music has not only transcended the mundane and the narcissistic, but it is still capable, as it has done in the past, of successfully challenging regressive political ideology. As the world is becoming increasingly fractured and polarised on countless issues, humanity needs Beethoven’s optimism even more urgently today than it did 200 years ago.

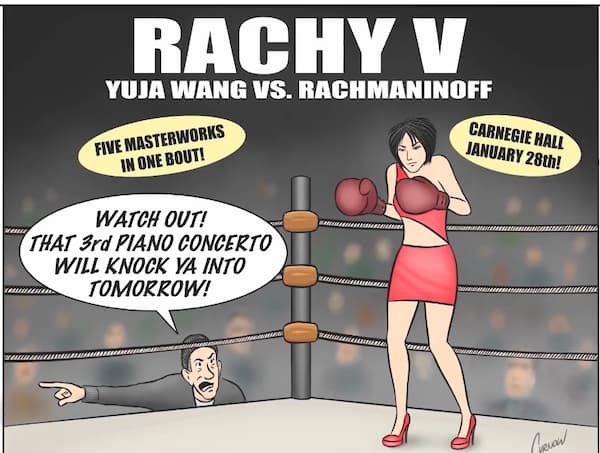

By Janet Horvath, Interlude

The ganjingworld investigation began with statistics: Yuja Wang has played so far, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2, thirty-five times, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 1, fourteen times, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 4, twenty-one times, Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini thirty-one times, and Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3, a total of 72 times.

No one had ever attempted playing all of Rachmaninoff’s five works for piano solo with the orchestra before. Who else would have the stamina to do it? It’s akin to winning a gold medal in the Olympics or climbing Mount Everest.

In planning the program, Yuja decided the 3rd Piano Concerto had to conclude the program as it is the epitome of emotion, drama, and physicality. Who can play anything after that?

Unsurprisingly, Wang’s virtuosity and musicality were riveting from beginning to end. Wang also amazed the audience with a different outfit for each concerto while keeping track of the tracking device.

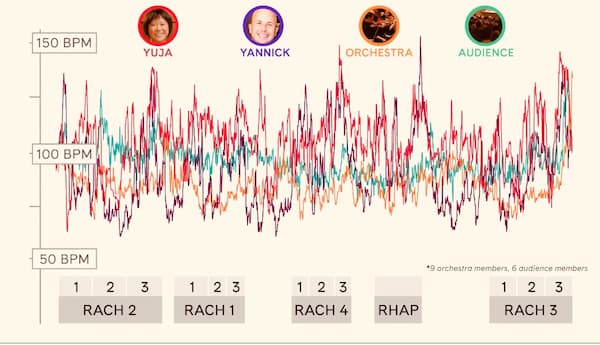

© Carnegie Hall

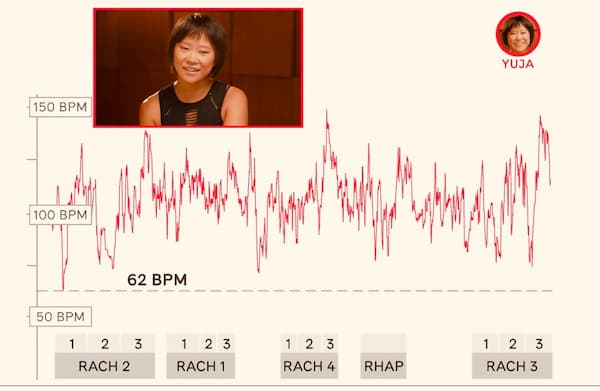

When the results were revealed to Wang, it was uncanny that she could look at the graph and identify exactly where she was in the music just by looking at the peaks and the valleys of her heartbeats.

The highest peaks, of course, occur where the music is physically or psychologically difficult. As a benchmark note, resting beats per minute is approximately 62 BPM. During the finale of the 2nd Concerto, her heart rate reached 139 BPM, predictably where there are more notes, and it’s faster and louder. During the finale of the 3rd Concerto, she surpassed that number at 146 BPM. But the highest level reached 149 BPM— 233% more than resting—was during the finale of the 4th Concerto.

The interesting thing is that Wang’s heart rate didn’t always consistently go up when it was loud and fast or just in the finales. In fact, the 3rd Concerto, despite being the longest and most difficult concerto, on average, indicated the lowest BPM rates. Wang thinks there are two reasons for this slower heart rate. Spiritually, the piece has a calming effect on her. Technically, as an elite and superbly skilled pianist, she’s able to save her energy when needed during the performance. Her heart rate is affected by how economical her movements are.

There is a third possibility to consider. Perhaps the reason her heartbeats were higher in the first and fourth concertos is that Wang has had the least experience performing these works. If she was more keyed up, it certainly would affect one’s heart rate.

Another statistic amused Yuja Wang. The numbers indicated how much harder she worked than the conductor. She: 2,427 calories burned and 20,275 steps taken; He: 1,645 calories burned and 15,079 steps taken.

Vindicated! We musicians know this! But Yannick actually recorded the highest peak, higher than any of Wang’s uppermost BPMs, when he reached 153 BPM in the final variations #19-24 of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. It is, of course, a very exciting ending, and it’s strenuous to marshal all the musicians for this mighty climax, as it is for us to play it.

Throughout his career, Nézet-Seguin has sought to bring people in sync with his music-making. He was astonished when he saw this reflected on the graph. There is an amazing synchronicity when comparing the heartbeats of the soloist and the conductor. Yuja and Yannick were musically and physically on the same wavelength throughout. But even more impressive, even during Wang’s cadenzas, when the orchestra and the conductor were “at rest,” their heartbeats rose in sync with the soloist’s playing and emotion. Whenever the music became more emotionally intense, the constant interdependence between all the musicians on stage, even when they weren’t playing, was notable. The phenomenon could be seen in the tracking devices of audience members as well. Their heartbeats went up, too, during the emotionally moving sections.

Does this occur in other settings? Choir music and song have permeated civilisations throughout different cultures and religions. In a 2013 study, it was documented that when choirs sing, their heartbeats become synchronized, beating as one. An article in NPR and the BBC World Service in July of 2013 reported that researchers of the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden studied the heart rates of a high school choir in a variety of choral works. They published their results in Frontiers in Neuroscience. Singers must exhale and inhale in a coordinated fashion. The findings showed that singing in a choir calmed the singer’s heart rate, especially when they were singing in unison, and within a few moments, each person’s heartbeat became synchronised. Somehow, the singers’ collective consciousness is connected to each other. Their controlled breathing, as we’ve seen in yoga and in other meditational practices, had a quietening effect.

Listen to The VocalEssence Ensemble Singers conducted by Philip Brunelle perform “The Day is Done” by Minnesota composer Stephen Paulus to a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “And the night shall be filled with music, And the cares, that infest the day, Shall be banished like restless feelings, That silently steal away.”

I can’t help respiring, sighing with them.

Stephen Paulus: The Day in Done

Choirs breathe together, but so do wind and brass musicians in a band, ensemble, or orchestra—to make a phrase, to play seamlessly, and to express the musical lines homogeneously. Many audience members may not know that string players must also breathe together, especially during chamber music performances when we don’t have a conductor. The sniff at the beginning of a piece, in addition to body language, will lead colleagues, much like a conductor’s upbeat, and the rate of the sniff indicates many things—when to play, the type of entrance, the rhythm, the meter, the style. Breathing helps us stay together and to feel the music as one.

The Yuja Wang Rachmaninoff Heartbeat Study was more than an amusing experiment. Dr. Bjorn Vickhoff concludes, “We speculate that it is possible singing could also be beneficial.” Performing and listening to music is good for us and is a positive experience which can synchronise our heartbeats. Unlike many other activities, music can bring people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds together, in sync, in harmony, despite wide-ranging experiences with music.

Here is the video of the entire study courtesy of Yuja Wang, and Carnegie Hall, director Joe Sabia, producer Greg T. Gordon, Images Carnegie Hall Rose Archives, Cartoon Jeffrey Curnow.