It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, November 6, 2024

15-Year-Old Karolina Protsenko plays "Love Theme" by Ennio Morricone

Monday, November 4, 2024

A Tribute to MARILYN MONROE

Marilyn Monroe In "River Of No Return" - "One Silver Dollar"

Friday, November 1, 2024

ABBA - Thank You For The Music

/ abba

Instagram:

/ abba

Instagram:  / abba

Twitter:

/ abba

Twitter:  / abba

TikTok:

/ abba

TikTok:  / abba

Read More About ABBA: http://www.abbasite.com/

Video produced by: Lasse Hallström

/ abba

Read More About ABBA: http://www.abbasite.com/

Video produced by: Lasse HallströmThe Dangers of being a Musical Prodigy

by Georg Predota

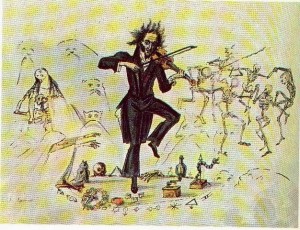

Niccolò Paganini left an irrefutable mark on the history of instrumental music and 19th century social life. Born in Genoa on 27 October 1782 he was the third of six children of Antonio and Teresa Paganini. Antonio Paganini was a dockworker and day laborer, managing to supplement his meager income by playing the mandolin. So he was absolutely delighted when young Niccolò displayed great musical talent at an early age. It was not his son’s musical talent that brought excitement to Antonio Paganini’s life, but the prospect of reaping substantial financial benefits from the boy’s musical talents. Antonio started Niccolò on the mandolin, but switched him to the violin at age 7. Giving musical instructions to this son was not a labor of love, as Niccolò later wrote. “My father Antonio soon recognized my natural talent and I have him to thank for teaching me the rudiments of the art. His principal passion kept him at home a great deal, trying by certain calculations and combinations to figure out lottery numbers from which he hoped to reap considerable gain. He therefore pondered over the matter a great deal and would not let me leave him, so that I had the violin in my hand from morn till night. It would be hard to conceive of a stricter father. If he didn’t think I was industrious enough, he compelled me to redouble my efforts by making me go without food so that I had to endure a great deal physically and my health began to give way.”

Niccolò Paganini left an irrefutable mark on the history of instrumental music and 19th century social life. Born in Genoa on 27 October 1782 he was the third of six children of Antonio and Teresa Paganini. Antonio Paganini was a dockworker and day laborer, managing to supplement his meager income by playing the mandolin. So he was absolutely delighted when young Niccolò displayed great musical talent at an early age. It was not his son’s musical talent that brought excitement to Antonio Paganini’s life, but the prospect of reaping substantial financial benefits from the boy’s musical talents. Antonio started Niccolò on the mandolin, but switched him to the violin at age 7. Giving musical instructions to this son was not a labor of love, as Niccolò later wrote. “My father Antonio soon recognized my natural talent and I have him to thank for teaching me the rudiments of the art. His principal passion kept him at home a great deal, trying by certain calculations and combinations to figure out lottery numbers from which he hoped to reap considerable gain. He therefore pondered over the matter a great deal and would not let me leave him, so that I had the violin in my hand from morn till night. It would be hard to conceive of a stricter father. If he didn’t think I was industrious enough, he compelled me to redouble my efforts by making me go without food so that I had to endure a great deal physically and my health began to give way.”

Niccolò Paganini: Sonata Concertata

Being forced to practice the violin up to 15 hours a day hardly seems a recipe for a healthy childhood. Neither is withholding food and water as punishment for lack of enthusiasm. “I really didn’t require such harsh stimulus,” writes Niccolò “because I was enthusiastic about my instrument and studied it unceasingly in order to discover new and hitherto unsuspected effects that would astound people.” As the immediate result of his father’s abuse, Niccolò health became so scarred that he would never fully recover. He also developed a serious drinking problem by the age of 16! But even more troubling were the psychological effects. He became obsessed with fame and money, and his relentless ambition translated into increasingly bizarre behavior. Supposedly, he was once invited to play at a funeral, but interrupted the ceremony with a twenty-minute solo concerto. And I am sure you’ve heard the story of him spending eight days in jail for drugging his girlfriend and forcing the abortion of his child.

Being forced to practice the violin up to 15 hours a day hardly seems a recipe for a healthy childhood. Neither is withholding food and water as punishment for lack of enthusiasm. “I really didn’t require such harsh stimulus,” writes Niccolò “because I was enthusiastic about my instrument and studied it unceasingly in order to discover new and hitherto unsuspected effects that would astound people.” As the immediate result of his father’s abuse, Niccolò health became so scarred that he would never fully recover. He also developed a serious drinking problem by the age of 16! But even more troubling were the psychological effects. He became obsessed with fame and money, and his relentless ambition translated into increasingly bizarre behavior. Supposedly, he was once invited to play at a funeral, but interrupted the ceremony with a twenty-minute solo concerto. And I am sure you’ve heard the story of him spending eight days in jail for drugging his girlfriend and forcing the abortion of his child.

15 Pieces of Classical Music About Trees

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

Classical composers are no exception. In fact, a huge percentage of them were great nature lovers (Beethoven, for one, often composed in his head during his walks), and many of them went so far as to write music inspired by forests.

Forest under bright sunlight © Flux AI Image Generator

Today, we’re looking at fifteen pieces of classical music about trees. Put on your hiking boots and join us!

Francesco Geminiani: La foresta incantata (1754)

Italian composer Francesco Geminiani lived from 1687 to 1762. He helped to popularise the Italian style of violin playing abroad, most famously in London.

He was widely admired during his lifetime, being considered the equal of composers like Handel and Corelli, but for whatever reason, he has fallen out of favour today.

In 1754, he wrote a pantomime ballet called La foresta incantata (“The Enchanted Forest”).

Franz Schubert: Der Lindenbaum from Winterreise (1827)

Winterreise (“Winter Journey”) is a series of twenty-four songs for voice and piano.

These two dozen songs are narrated by a man who, when he hears of his beloved’s betrothal to another, goes on a wintertime journey to escape the memory of her.

Der Lindenbaum (“The Linden Tree”) is the fifth song of the cycle. In it, the narrator notices a linden tree as he travels. It serves as a reminder of happier days, during which he used to sit under one and enjoy his day.

As he passes, the linden tree seems to call out to him. However, he doesn’t turn back. Instead, he leaves the tree and all the memories it represents and keeps travelling forward into an uncertain, unsettled future.

Vincent d’Indy: La Forêt Enchantée (1878)

French composer Vincent d’Indy wrote La Forêt Enchantée in 1878 when he was just twenty-seven years old.

At the time, Wagner was a major influence on the young composer (as he was to many young composers), and you can really hear that influence here.

In this piece, d’Indy follows the story of a knight named Harald, who visits an enchanted forest and meets seductive elves. In the finale, he drinks from an enchanted forest lake and falls into a deep sleep.

Franz Liszt: Waldesrauschen (1862-63)

In the early 1860s, pianist and composer Franz Liszt wrote two concert etudes. The first is called Waldesrauschen, or “Forest Murmurs.”

This piece uses the piano to imitate the sound of breezes blowing through trees. Those breezes begin very quietly with a marking of vivace, or “in a lively manner.” Eventually, the work and the wind become loud and passionate.

Johann Strauss II: Tales from the Vienna Woods (1868)

One of the most famous parts of Vienna is its woods, found just outside the city. It’s a sizable woods: almost thirty miles long and between twelve to eighteen miles wide.

Julius Schmid: Beethoven’s Walk in Nature

Schubert and Beethoven often found creative inspiration in those woods, and so did Johann Strauss II.

In 1868, he wrote one of his famous waltzes (which is actually an arrangement of multiple waltzes) and called it Tales from the Vienna Woods.

It was inspired by the dances of the rural citizens. To imitate folk instruments, Strauss employed a zither.

Alexander Glazunov: The Forest (1887)

Russian composer Alexander Glazunov wrote an orchestral fantasy called The Forest at the age of twenty-two.

He wrote an entire program for it, describing in exacting detail what he’d seen in his mind’s eye: daybreak, birds chirping, the appearance of nymphs, a hunting party, and finally, more bird calls.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: The Forest of Fir Trees in Winter from The Nutcracker (1892)

Every ballet lover knows the story of The Nutcracker. A little girl named Clara receives an enchanted nutcracker doll on Christmas Eve. In the middle of the night, Clara visits the doll while the rest of the household is asleep – and magical events transpire.

After witnessing a battle between gingerbread soldiers and mice, Clara is astonished to see the nutcracker turn into a handsome prince.

The ballet’s first act ends when the prince leads her into a forest as snow falls. This stunning music by Tchaikovsky accompanies their journey.

Edward MacDowell: To an Old White Pine from New England Idyls (1896)

In 1896, American composer Edward MacDowell and his wife moved into a farmhouse in the New Hampshire countryside.

MacDowell was deeply inspired by his New England surroundings. In 1902, he wrote a series of ten piano miniatures depicting various natural phenomena and history, including “An Old Garden” and “From Puritan Days.”

The seventh in the set of ten is called “To an Old White Pine.” There is a brief poem at the top of the score:

A giant of an ancient race

He stands, a stubborn sentinel

O’er swaying, gentle forest trees

That whisper at his feet.

John Ireland: The Almond Trees (1913)

John Ireland was an English composer born in 1879. He began his musical studies with piano and organ, then became interested in composition in the late 1890s.

The Almond Trees is a slender, evocative, meandering work with a real Impressionist tinge.

Jean Sibelius: The Trees (1914)

Finnish composer Jean Sibelius may be best-known for his symphonies, but his piano music is worth checking out, too.

One of the loveliest examples is The Trees, a collection of five sensitive pieces for solo piano.

Each movement is named after a particular species of tree: When the Rowan Blossoms, The Solitary Pine, The Aspen, The Birch and The Spruce.

Ottorino Respighi: The Pines of Rome (1924)

The Pines of Rome is an orchestral tone poem in four movements, and possibly the most famous example of tree-inspired classical music.

The pines at the Villa Borghese

Each of the four movements portrays pines in a particular location in Rome: The Pines of the Villa Borghese, Pines Near a Catacomb, The Pines of the Janiculum, and The Pines of the Appian Way.

The piece moves backwards in time in a striking way. The first movement portrays children playing in twentieth-century Rome, but with each movement, Respighi goes further back in time, and by the end, he’s depicting a legion of Roman soldiers marching down the tree-lined Appian Way.

Arnold Bax: The Tale the Pine Trees Knew (1931)

While listening to the ominous opening measures to Arnold Bax’s tone poem The Tale the Pine Trees Knew, one wonders what dark events these trees have witnessed.

We’re left to speculate since Bax didn’t leave a concrete program.

However, he did at least mention that the work was inspired by visits to Norway and Scotland. He wrote:

This work is concerned solely with the abstract mood of these places, and the pine trees’ tale must be taken purely as a generic one. Certainly, I had no specific coniferous story to relate.

Igor Stravinsky: Dumbarton Oaks (1937-38)

In the late 1930s, American diplomat and philanthropist Robert Woods Bliss and his wife Mildred Barnes Bliss gave themselves quite the anniversary gift: they commissioned a work by Igor Stravinsky!

Stravinsky answered the call by writing this attractive neoclassical concerto for chamber orchestra.

It was named after Dumbarton Oaks, the Bliss’s massive estate in Georgetown, Washington, DC.

If the name sounds familiar to you, it might be because a few years later, in 1944, the Dumbarton Oaks Conference was held at the estate. Participants came out of the conference with proposals for the establishment of what ultimately became the United Nations.

L’arbre des songes by Henri Dutilleux (1983-85)

French composer Henri Dutilleux wrote L’arbre des songes (or “The Tree of Dreams”) in the mid-1980s. It’s a four-movement violin concerto that was dedicated to violinist Isaac Stern.

Dutilleux described it like this:

All in all the piece grows somewhat like a tree, for the constant multiplication and renewal of its branches is the lyrical essence of the tree. This symbolic image, as well as the notion of a seasonal cycle, inspired my choice of ‘L’arbre des songes’ as the title of the piece.

Treesong by John Williams (2001)

American composer John Williams also took inspiration from trees when writing this violin concerto.

He found himself drawn to a particular tree at the Boston Public Garden: in his words, “a beautiful specimen of the Chinese dawn redwood, or metasequoia.”

This species of tree was once thought to have gone extinct. Fortunately, however, some modern-day examples were discovered, thereby saving the species and enabling modern humans to enjoy them.

Later, Williams met Dr. Shiu-Ying Hu, a botanist from Harvard. While they were walking in the Arnold Arboretum, she pointed out the oldest metasequoia and told the story of how she planted it in the 1940s.

“I was thunderstruck by this coincidence, and when I told her of ‘my’ metasequoia in the Public Garden, she informed me that the younger tree I loved so much was also one of her children,” Williams wrote.

The awe and human warmth of this realisation, along with Williams’s love for these trees, colours TreeSong.

Conclusion

From John Williams’s portrait of redwoods to Geminiani’s portrait of an enchanted forest, it’s clear that composers from every generation have enjoyed branching out by writing tree-inspired music, and there will surely be more tree-inspired music to come!

Which of these works best evokes the magic of trees? Have we missed any of your favourites? Let us know!

The 10 Most Beautiful Piano Quintets in Classical Music

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

Piano Quintet

Interestingly, piano quintets are less common than keyboard chamber music for smaller ensembles, probably because of the challenges of clearly defining the relationship between piano and strings. Piano quintets had been written before, but it was only by the middle of the 19th century that this particular genre took on the seriousness of other prestigious chamber music genres.

Are you ready to explore the 10 most beautiful piano quintets in standardised scoring? Once again, we do have a rather substantial number of works on offer, and all playlists of this kind are subject to personal taste. However, one thing we can probably agree on is that the Schumann E-flat Major Piano Quintet is one of the greatest works in this genre.

Robert Schumann: Piano Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 44

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) was rather severely harassed by his sceptical father-in-law. In order to prove potential earnings from composition, Schumann wrote over one hundred songs in 1840. In 1841, he wrote nothing but symphonic works, and in 1842, he turned his attention towards chamber music. To prepare, he studied quartets by Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, and composed a piano trio, three string quartets, a piano quartet, and the Piano Quintet Op. 44.

Dedicated to his wife Clara, Schumann featured a complete string quartet with added piano. The opening “Allegro brillante” features a bold and sparkling musical idea that organically expands. Almost immediately, however, this is contrasted by a soft and tender dialogue between the viola and the cello. In due course, both themes are extensively fragmented and subjected to far-reaching modulations. The second movement unfolds in the manner of a funeral march, with a dark and mysterious melody accompanied by sobbing musical rhythms.

Robert Schumann, 1850 © pianolit.com

The “Scherzo” joyously and exuberantly presents ascending and descending major scales, contrasted by two “Trios,” which sound a lyrical canon and Hungarian gypsy music, respectively. Schumann’s contrapuntal and expressive prowess emerges in the concluding “Allegro”, as he blends strict canonic and fugal passages with passages of nervous lyricism. The coda is cast as a double fugue and breathtakingly combines the main themes of the first and last movements.

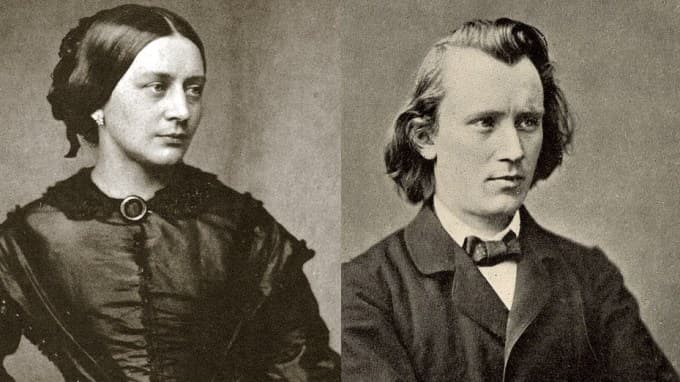

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34

In terms of the Piano Quintet, it is difficult to say Schumann without also saying Brahms. However, the marvellous Brahms Piano Quintet started out as a quintet for two violins, viola, and two cellos. Clara Schumann was enthusiastic and praised that “inner strength and richness written for the instruments.” However, when Brahms sent it to Joseph Joachim, the famous violinist had reservations and suggested that it “lacked charm and sounded artificial in spots.”

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

Not entirely confident in his abilities, Brahms reworked the piece as a piano sonata for two pianos. When he played it with Clara, she was overwhelmed by the music’s grandeur but refused to call it a sonata. As Clara wrote, “it is so full of ideas that it requires an orchestra for its interpretation.” Brahm once again started to transform the work, and it was the conductor Hermann Levi who suggested that it should be recast as a piano quintet.

In the end, the piano quintet is a hybrid of two earlier versions, combining Brahms’ youthful exuberance with sophisticated musical textures and a logical way of constructing motives and their subsequent development and continuation. When Levi heard the finished composition in 1865, he wrote, “The quintet is beautiful beyond measure; Out of the monotony of the two pianos a model of tonal beauty has arisen; a restorative for every music-lover, a masterpiece of chamber music.”

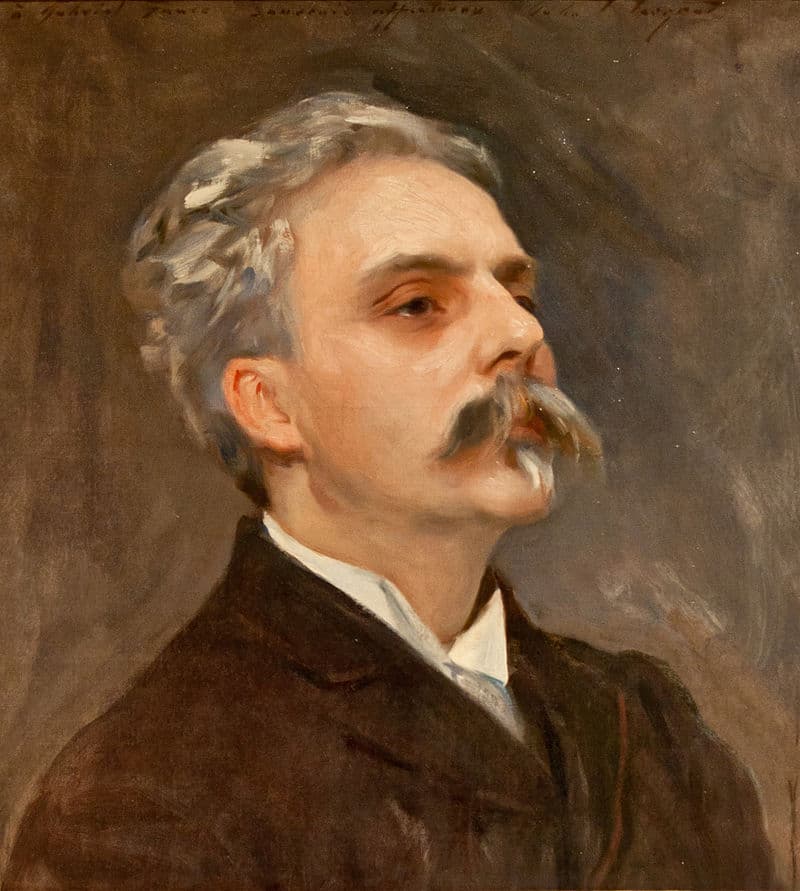

Gabriel Fauré: Piano Quintet No. 1 in D minor, Op. 89

Not unlike Brahms, it took Gabriel Fauré a number of years before he came to terms with his first Piano Quintet. First published in 1906, drafts for the work actually date from 1887. Four years later, Fauré contemplated the addition of a second violin to what might have been a third piano quartet. After drafting two movements, he put the work aside once more and only returned to work again in 1903. The composer referred to the work as “this animal of a quintet”, and the piece was finally completed towards the end of 1905.

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1896

The work is dedicated to Eugène Ysaÿe, and a first performance in Brussels with the Ysaÿe Quartet in March 1906 was repeated in Paris the following month. Commentators heard a “strangely inward melancholy” possibly connected to some medical problems the composer experienced during the 1880s. Fauré experienced dizziness and severe headaches, and suffered from depression possibly related to the death of his father in 1885. He also started to experience hearing loss, which began to affect him in earnest in 1902. Fauré grew tired “of repeating himself endlessly in his music,” but the Op. 89 Piano Quintet stands apart from his other chamber works, including his 2nd Piano Quintet, Opus 115.

Jean Sibelius: Piano Quintet in G minor

Jean Sibelius

On 19 January 1890, Ferruccio Busoni performed the Piano Quintet in E minor, Op. 5 by the Norwegian composer Christian Sinding at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. In the audience, by invitation from Busoni, was Jean Sibelius. It has long been suspected that this occasion provided the impulse for Sibelius to start work on his own five-movement Piano Quintet in G minor. The work was completed in April 1890, and the first concert performance took place in Helsinki, with Busoni playing the piano part.

While Busoni greatly admired the composition, Sibelius’ former composition teacher, Martin Wegelius, was highly critical of the piano writing, especially in the first movement. As he commented, “his curious whims and fancies have obscured his real self.” Surprisingly, the “Finale” was never performed during the composer’s lifetime, and it first sounded in public only in 1965. A scholar writes, “maybe Sibelius feared that it would never actually be performed and wished to salvage some of its musical material; or perhaps he felt that he had not exhausted the potential of its themes.” In the event, the Piano Quintet is one of the most impressive chamber works by Sibelius, with the composer “striving for a new ruggedness and severity of mood.”

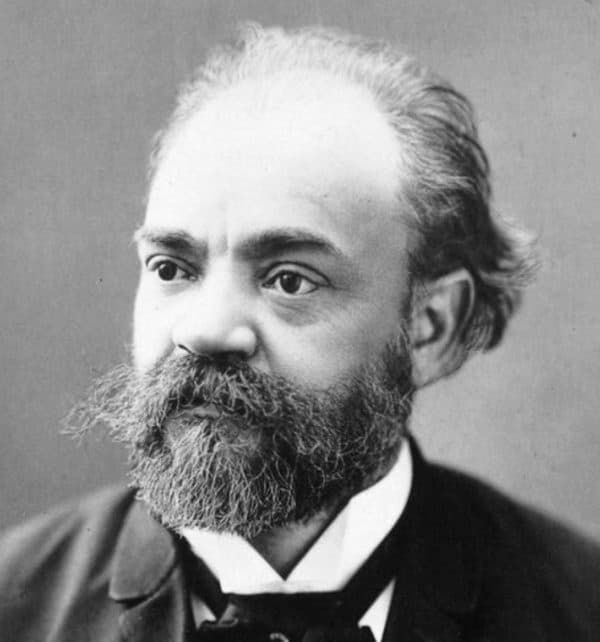

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Quintet in A Major

Following in the footsteps of his idol Johannes Brahms, Antonín Dvorák (1841- 1904) exhibited a heightened sense of musical insecurity. The Piano Quintet in A Major, published as Op. 5 in 1872, makes a convincing case in point. Although received enthusiastically by critics and audiences alike, Dvorák remained highly dissatisfied with the work and destroyed the manuscript soon after its premiere.

Dvořák in New York, 1893

Fifteen years later, the composer reconsidered and began to make extensive revisions to the work. However, rather than submitting the revised work for publication, he cast it aside for good and instead worked on a brand new quintet in the same key. The resulting Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 81 not only secured Dvorák’s international reputation but also produced a distinctive masterpiece of Nineteenth-Century chamber music.

The gently flowing piano accompaniment provides the colouristic background to one of Dvorák’s most expressive and lyrical melodies, stated in the cello. However, this sense of tranquillity is suddenly interrupted by a rhythmically animated transition in the minor mode that propels the music forward. This process is once repeated before the viola sings another lyrical melody. Subsequently, both themes are thoroughly developed—relying predominantly on the first and second violin—before a rhapsodic recapitulation feeds into a sparkling and virtuosic coda. The second movement invokes a Ukrainian lament, known as “Dumka,” and the ”Scherzo” is cast in the style of a Bohemian folk dance called “Furiant.” Not to be outdone, the “Finale” presents yet another vigorous dance, a Polka.

Edward Elgar: Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 84

Edward Elgar was born in a small village and initially earned his living by working in the office of a local solicitor. He received no formal musical training, but nevertheless succeeded his father as organist and played the violin in an orchestra at Birmingham. His early attempts at composition are patterned after the music of Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms and Wagner, but plans to attend the Leipzig Conservatory were never realized.

Edward Elgar

With his A minor quintet, one of three chamber compositions dating from the concluding years of WWI, Elgar returned to the themes and musical aspirations of his youth. Unwilling to participate in modernist musical experimentations, Elgar provided a summary review of 19th-century European musical practices from a distinctly English perspective.

The first movement opens with a hauntingly beautiful introduction that canvasses a slow-moving melodic fragment played by the piano against a rhythmically animated commentary given by the strings. Sounding at once rhapsodic and almost improvisatory in nature, Elgar himself described the introduction as “ghostly stuff.” The opening movement clearly pays homage to Brahms’s musical personality, while the “Adagio” explores the musical tensions of an extended emotional narrative. The final movement, which also relies on a slow musical introduction, provides the fitting nostalgic conclusion to Elgar’s musical gesture of resignation.

Béla Bartók: Piano Quintet in C Major

Let’s now turn to Béla Bartók (1881-1945), one of the most influential figures in the history of classical music. Composer, performer, educator, and ethnomusicologist, Bartók powerfully shaped the way subsequent generations approached and listened to music. Bartók displayed great musical talent at an early age. He could distinguish between different tunes and rhythms before he started talking, and by age 4 he had roughly 40 pieces in his piano repertory.

Béla Bartók in New York, 1944

Bartók composed the four movements of his Piano Quintet in 1903 and 1904, and thematically, they are reminiscent of the music of Johannes Brahms and Richard Strauss. Yet, Bartók was not slavishly following traditional compositional standards. In the final two movements, we find early inclusions of folk elements, resulting in a distinctive Hungarian flavour.

A tightly organised formal structure builds on the continual repetition and variations of themes and unfolds within a highly flexible tonal space. The consistent use of asymmetrical rhythms completes a vocabulary of stylistic features that would soon become familiar elements of Bartók’s expressive language. For one reason or another, Bartók had to be persuaded not to destroy this composition. Thankfully, he took the manuscript with him to the United States, where it was published after his death.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 57

My list of top 10 Piano Quintets must necessarily include the G-minor work by Dmitry Shostakovich. It was composed during the summer of 1940 and written for the Beethoven Quartet and himself. The work followed on the heels of his Sixth Symphony, a work that received a rather mixed reception. The success of the Piano Quintet, however, was unqualified and long-lasting. In fact, the composition was awarded a Stalin Prize of 100,000 rubles.

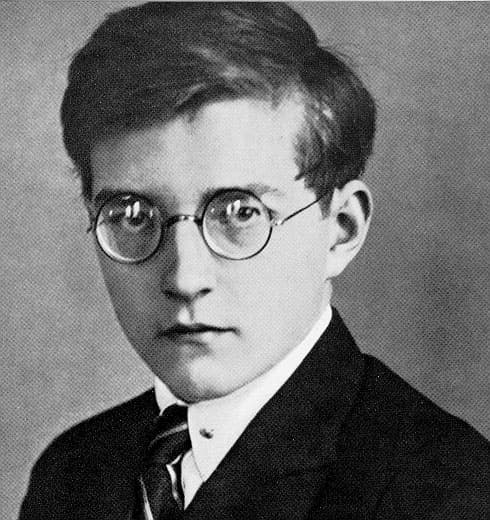

Dmitry Shostakovich, 1925

Robert Matthew-Walker writes, “a glance at the list of movements might lead one to imagine that this is a neoclassical work, but its direct emotional power and thematic integration place it on altogether a higher level than mere pastiche.” The opening movement titled “Prelude” opens with a declamatory three-note cell that provokes an impassioned response from the strings. The four-voiced “Fugue” begins with a strict exposition by muted strings that build into an elegiac web of sound, eventually joined by the piano adding a bass line.

The music continues immediately with a whirlwind “Scherzo,” with the piano presenting a witty theme that interacts with the strings. The first trio sounds a gypsy-like air, while the second involves playful pizzicato. A cool and relaxed “Intermezzo” unfolds over a walking bass accompaniment in the cello, with the remaining strings sounding a bitter-sweet counterpoint. In the “Finale,” the piano sounds a gentle theme over an animated accompaniment. Once the mood quietens, the work returns to the impassioned beginning but ends in a quiet and contented close.

Nicolai Medtner: Piano Quintet in C Major

Nicolai Medtner, who died in London on 13 November 1951, was one of the very last Romantic composer-pianists. Overshadowed by his contemporaries Scriabin and Rachmaninoff, Medtner made the piano the focus of his creative activity and frequently tempered a Russian spirit with music firmly rooted in the Western classical tradition. A scholar writes, “Fully developed almost from the time of his first published works, his musical idiom changed very little throughout his career, and his entire output is remarkably consistent in quality.”

Sadly, the Piano Quintet in C Major was Medtner’s final composition on which he had worked intermittently for almost 45 years. Initial sketches date from 1904 and 1905, and the work was completed towards the end of 1948. A severe heart attack prevented the composer from rehearsing and recording it. Jeremy Lee writes, “Fervent, sincere, personal, and above all intensely soulful, Medtner’s Piano Quintet certainly is one of the most deeply satisfying works ever written.”

Grażyna Bacewicz: Piano Quintet No.1

Let me conclude my list of the 10 most beautiful piano quintets with a work by the Polish violinist, pianist, and composer Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969). One of the most significant voices in European music of the twentieth century, she studied with Nadia Boulanger and the violinists André Touret and Carl Flesch. Her compositional development initially focused on clarity, wit and brevity, while her works from the time of World War II “show a greater muscularity and daring disregard for traditional classical structures.”

Grażyna Bacewicz

Her first piano quintet dates from 1952, and it presents a sound world that mediates between folkloric impulses “and the developmental rigour of classical principles.” It is a highly personal work, and you can hear the use of folk materials directly and indirectly. I hope you enjoyed my selections, but for every piano quintet featured, I had to sadly neglect some equally wonderful choices. The Borodin quintet is fantastic, as are the piano quintets by Rubinstein, Franck, Bruch, Suk, Vierne, Granados, Reger, Amy Beach, Bax, Dohnányi, Milhaud, and many others; would you like to see some of them featured?