It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, January 19, 2024

Tony Bennett, Amy Winehouse - Body and Soul

19 January: Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1 Was Premiered

By Georg Predota, Interlude

Saint-Saëns, 1875

On 19 January 1873, the French cellist, viola da gamba player and instrument maker Auguste Tolbecque premiered Camille Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 33, a work specifically composed for him. Tolbecque was a close personal friend, and the solo cellist of the Conservatoire orchestra. He was a composer himself, and also a published music historian. Tolbecque was influential in the performance of early music as he conducted research into historical instruments and their restoration.

Saint-Saëns as a boy, 1846

His compositions tend to be light in style and influenced by Mendelssohn and Schumann. Tolbecque retired before he was able to produce a recording, and he does not figure prominently in the review of the Saint-Saëns concerto published in the Revue et gazette musicale de Paris immediately after the premiere. “If Mr. Saint-Saëns should decide to continue in this vein,” the reviewer wrote, “which is consistent with his violin concerto, the Trio in F, and other works of lesser significance, he is certain to recover many of the votes that he lost with his all-too-obvious divergence from classicism and the tendencies in a number of his recent works. We must say that the Cello Concerto seems to us to be a beautiful and good work of excellent sentiment and perfect cohesiveness, and as usual the form is of greatest interest.”

Auguste Tolbecque

At the time Saint-Saëns composed his first Cello Concerto he had already reached the age of thirty-seven. He was highly regarded in French musical circles, but as a composer he was still searching for his breakthrough work. He clearly possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness and productivity was compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Although he was living in a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional. Romain Rolland wrote in 1908, “He brings into the midst of our modern restlessness something of the sweetness and clarity of past periods, something that seems like fragments of a vanished world.” In his first Cello Concert, Saint-Saëns takes a deliberate stance away from what the critic calls “the (modernist) tendencies in a number of his recent works.” His unmistakable melodic charm and characteristic freshness and vitality are clothed in a formal clarity that undoubtedly accounts for the widespread popularity the 1st Cello Concerto enjoyed from the very onset.

Opening of Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1

For Saint-Saëns, “form was the essence of art.” As he once wrote, “the music-lover is most of all enchanted by expressiveness and passion, but that is not the case for the artist. An artist who does not feel a deep sense of personal satisfaction with elegant lines, harmonious colors or a perfect progression of chords has no comprehension of true art.” As the anonymous critic had written after the premiere, “it should be clarified that this is in reality a “Concertstück,” since the three relatively short movements run together. The orchestra plays such a major role that it gives the work symphonic character, a tendency present in every concerto of any significance since Beethoven.” Saint-Saëns might have been looking at Franz Liszt, a composer he greatly admired, as the three movements of the concerto are interconnected. In fact, the principle theme is sounded in legato running triplets, and it appears in all movements of the concerto.

Saint-Saëns, circa 1880

Sir Donald Francis Tovey later wrote “Here, for once, is a violoncello concerto in which the solo instrument displays every register without the slightest difficulty in penetrating the orchestra.” The orchestra clearly plays a role beyond that of mere accompaniment, “as this work never succumbs to the imbalance frequently encountered in cello concertos whereby for long stretches the soloist is seen bowing furiously but is scarcely heard.” As Saint-Saëns tellingly suggested, “Virtuosity gives a composer wings with which to soar above the commonplace and the platitudinous.” Uniting the lyrical quality of the cello with instrumental virtuosity and carful orchestral scoring produced a work valued by performers and loved by audiences. But what is more, a good many composers, including Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff considered Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1 to be the greatest of all cello concertos.

Saint-Saëns: 1. Cellokonzert ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Gautier Capuçon ∙ ...

Sir Stephen Hough: The Composer

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Sir Stephen Hough

While his achievements as a pianist are well-known and documented, Hough is also a respected author with four books and hundreds of articles to his name. In addition, a solo exhibition of his paintings was presented in London in 2012. It’s hardly surprising that The Economist included him in the list of “Twenty Living Polymaths.”

In addition, Hough is also a published and frequently commissioned composer, having crafted works for orchestra, choir, chamber ensemble, organ, harpsichord, and solo piano. He has received commissions from the Takács Quartet, the Cliburn, the Berlin Philharmonic Wind Quintet, and the Gilmore Foundation, among many others.

First Compositions

According to his father, Hough had memorised seventy nursery rhymes by the age of two. Be that as it may, singing was indeed his first form of musical expression, “especially as we had no classical music in my childhood home.” Hough sang hymns in primary school and church; later, he joined a choir in high school, and he joined the compulsory chorus at Julliard.

Hough started piano lessons at the age of six, and he began to compose at around the same time. He remembers writing a “Mass” in his teenage years, but Hough is generally dismissive of his juvenilia compositions. As he writes, “the Mass

Transcriptions

Apparently, Hough composed a substantial number of works, but as he related in an interview, “mercifully, that pile of smudged sketches has disappeared.” These early efforts culminated in a viola sonata, the only early work that was actually published. However, for the next twenty odd years, Hough composed next to nothing, except an odd transcription or two. Hough related the story that after a recital in New York in the late 1990s, when he played his transcription of Rodger’s Carousel Waltz, he was chatting with the composer John Corigliano.

Corigliano told Hough, “You should compose your own music. The only real difference between a transcription and writing your own pieces is using your themes rather than someone else’s.” This conversation became the starting point for a renewed engagement with compositions. Hough started to write little pieces for friends, and the bassoonist Graham Salvage from the Hallé Orchestra asked him to write a concerto. As Hough explained, “In a mad moment or reckless courage, I agreed to have a go and started sketching what eventually became The Loneliest Wilderness, my first serious piece in two decades.”

First Commissions

The Loneliest Wilderness was inspired by the poem “My Company” by Herbert Read (1893–1968), containing the following lines:

But, God! I know that I’ll stand

Someday in the loneliest wilderness,

Someday my heart will cry

For the soul that has been, but that now

Is scatter’d with the winds,

Deceased and devoid.

I know that I’ll wander with a cry:

‘O beautiful men, O men I loved,

O whither are you gone, my company?’

The work is based on two main musical ideas: the interval of a descending fourth and a rising chain of thirds. Introvert and restrained, this musical oration has a strong Jewish flavour to it, taking its inspiration from “the heart-breaking regret of an army officer as he looks back at the loss of the company of soldiers under his command.”

Takács Quartet

Stephen Hough’s String Quartet No. 1

Dedicated to the Takács Quartet, Hough’s first string quartet premiered in December 2021. As it was commissioned as a companion piece to works by Ravel and Dutilleux, the composer set out to explore “not so much what united their musical language, but what was absent from them.” Although there are no quotes or direct references to the composers of Les Six, as captioned in the subtitle, the composer imagines unspecified places and memory where meetings might have taken place.

This string quartet “evokes a flavour more than a style,” according to Hough, “but a flavour rarely found in the music of Ravel and Dutilleux. In Les Six it’s not so much a lack of seriousness, although seeing life through a burlesque lens is one recurring ingredient; rather it’s an aesthetic re-view of the world after the catastrophe of the Great War. Composers like Poulenc and Milhaud were able to discover poignance in the rough and tumble of daily human life in a way which escaped the fastidiousness of those other two composers.”

Sonatas and Beyond

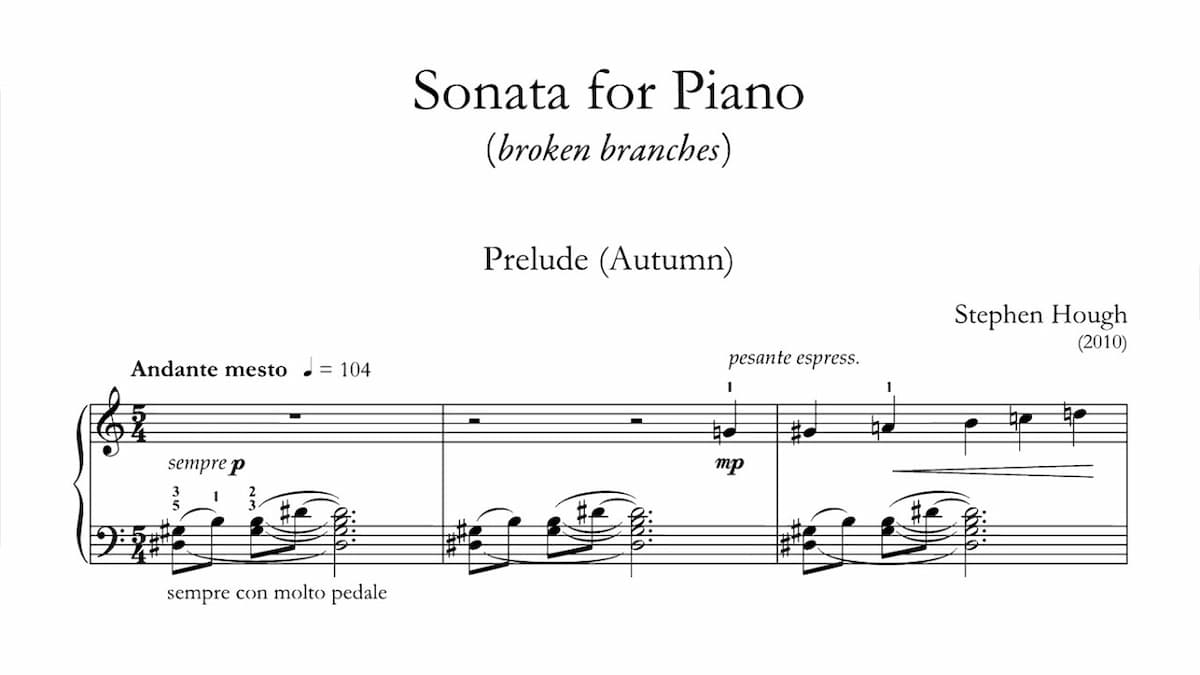

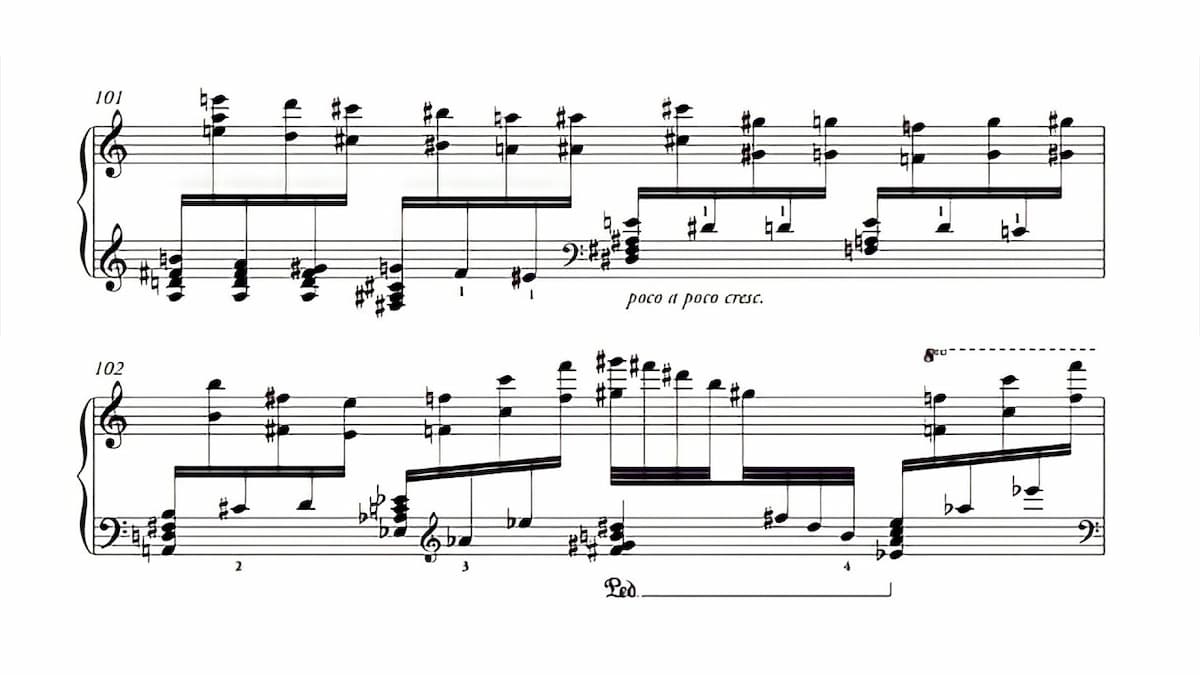

Stephen Hough’s Broken Branches

The term “Sonata” had a multiplicity of meanings over the years, but for Hough “it has kept its wordlessness and its seriousness; a sonata, regardless of form, is a statement of unity, if not uniformity.” And although the composer is wary of words or descriptions attached to them, he argues that “music is neither a thought nor an emotion nor a person, but very much its own entity. His sonata “Broken Branches,” is an oblique tribute to Janáček’s On an Overgrown Path, and a passage from Scripture: “I am the vine, you are the branches. Cut off from me you can do nothing.”

The sonata is constructed of sixteen small and inconclusive sections, like branches from a single tree. “Broken branches” functions in three ways; fragments of fragility, related in theme but incomplete and damaged.” The work seems to grow naturally out of Hough’s style of playing, and it opens with a “Prelude” and ends with a “Postlude” of identical music, but the anguish of the opening G-sharp minor becomes a glowing G major at the end. “Branches beginning life anew in a new spring.” The climax of this sonata is a section called “non credo,” based on “material from the Credo of my Missa Mirabilis, which explores issues of doubt and despair in the context of the concrete affirmations of the Nicene Creed.”

A Statement of Faith

Stephen Hough joined the Roman Catholic Church at the age of 19, and he considered becoming a priest, in particular joining the Franciscan Order. Hough has extensively written about his homosexuality and its relationship with music and his religion. As he wrote, “Catholicism is still home for me. And despite everything, I haven’t found anything that suits me better.” Hough is attracted to the idea that Catholicism doesn’t emphasise rich and powerful people, but embraces poverty and simplicity. “Christianity celebrates what is ultimately important about being human—community, and concern for the widows, the prisoners, the prostitutes, people who are outcasts. I find that very attractive.”

The Missa Mirabilis is connected with a highly personal experience. Hough had been working on the piece for about one year when he had a serious car accident, overturning his car on the motorway at 80 mph. “I stepped out of the one untouched door in my completely mangled car,” he remembers, “with my Mass manuscript and my body intact, then wrote part of the “Agnus Dei” in St. Mary’s Hospital, waiting for four hours for a brain scan. I was conscious, as I was somersaulting with screeching metallic acrobatics on the M1, of feeling regret that I would never get to hear the music on which I’d been working so intensely in the days before. Someone had other ideas.”

The Partita was commissioned by the Naumburg Foundation for Albert Cano Smit in 2019. As Hough explains, “composing four sonatas of a serious, intense character, I wanted to write something different – something brighter, something more celebratory, more nostalgic.” Scored in five movements, the outer movements “Overture” and “Toccata” are inspired by the world of a grand cathedral organ. The short three inner movements, “Capriccio,” and “Canción y Danza I & II,” are based on the interval of a fifth and partially represent an explicit homage to Federico Mompou.

Stephen Hough’s Fanfare Toccata

In 2002, Hough was commissioned to write a work for the 2022 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, performed by all 30 competitors. Hough took his inspiration from a variety of toccatas he had learned over the years, including Scarlatti, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff, Poulenc, Prokofiev and Samuel Barber. This inspiration accounted for the fanfare flourish complemented by a deeply romantic tune. It really does speak well of Hough’s composition that all 30 competitors have decided to make the Fanfare Toccata a part of their regular recital repertoire.

Thursday, January 18, 2024

Mozart: Requiem – Lacrimosa | SO & GC | CM Berlin

Diana Krall - So Nice (Live In Rio)

Tony Bennett - Fly Me to the Moon (Official Audio)

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

'La Donna E Mobile'

'La Donna E Mobile'

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/164445553-56a153915f9b58b7d0be4d2d.jpg)

Hiroyuki Ito/Hulton Archive / Getty Images

The aria for lyric tenors known as "La donna e mobile" is the centerpiece of the opera "Rigoletto," Giuseppe Verdi's twisted tale of lust, desire, love, and deceit. Composed between 1850 and 1851, Rigoletto was adored by audiences when it first premiered at La Fenice in Venice on March 11, 1851, and even now, over 150 years later, it is one of the world's most performed operas. According to Operabase, which gathers statistical information from opera houses around the world, Verdi's "Rigoletto" was the 8th-most performed opera in the world during the 2014/15 season.

The Context of "La Donna e Mobile"

The Duke of Mantua sings this unforgettable aria in the third act of Verdi's Rigoletto as he flirts with Maddalena, the sister of the assassin Sparafucile. Rigoletto, the Duke's right-hand man, and his daughter, Gilda, who has fallen in love with the Duke, pay a visit to Sparafucile. Rigoletto is very protective of his daughter and wants to have the Duke killed since he is a man that cannot be trusted with women.

When they reach the inn in which Sparafucile is staying, they hear the Duke's voice bellowing within singing "La donna e mobile" ("Woman is fickle") as he puts on a show for Maddalena with hopes of seducing her. Rigoletto tells Gilda to disguise herself as a man and escape to a nearby town. She follows his instructions and sets out into the night while Rigoletto enters the inn after the Duke leaves.

When Rigoletto makes a deal with Sparafucile and hands over his payment, a calamitous storm rolls in for the night. Rigoletto decides to pay for a room at the inn, and Gilda is forced to return to her father after the road to the nearby town becomes too dangerous to traverse. Gilda, still disguised as a man, arrives just in time to hear Maddalena make a deal with her brother to spare the Duke's life and instead kill the next man that walks into the inn. They will bag the body together and give it to the duped Rigoletto. Despite his nature, Gilda still loves the Duke deeply and resolves herself to put an end to this dilemma.

Italian Lyrics of "La donna e mobile"

La donna è mobile

Qual piuma al vento,

Muta d'accento — e di pensier.

Sempre un amabile,

Leggiadro viso,

In pianto o in riso, — è menzognero.

È sempre misero

Chi a lei s'affida,

Chi le confida — mal cauto il cuore!

Pur mai non sentesi

Felice appieno

Chi su quel seno — non liba amore!

La donna è mobile

Qual piuma al vento,

Muta d'accento — e di pensier,

E di pensier,

E di pensier!

English Translation

Woman is fickle

Like a feather in the wind,

She changes her voice — and her mind.

Always sweet,

Pretty face,

In tears or in laughter, — she is always lying.

Always miserable

Is he who trusts her,

He who confides in her — his unwary heart!

Yet one never feels

Fully happy

Who on that bosom — does not drink love!

Woman is fickle

Like a feather in the wind,

She changes her voice — and her mind,

And her mind,

And her mind!

Giuseppe Verdi, Và pensiero (Nabucco)

Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 • Volker Hartung • Cologne New Philharmonie

MSO celebrates 98 years of music with grand concert

Guest conductor Olivier Ochanine and Filipino violinist Diomedes Saraza Jr.

By MANILA TIMES

Embarking on the illustrious journey towards its centennial milestone, the Manila Symphony Orchestra joyously commemorates its 98th anniversary with a captivating concert gala that will bring together the elegant and graceful sound of the violin and the majestic but lyrical timbre of the MSO.

Titled "Peña, Nielsen, & Tchaikovsky: The MSO 98th Anniversary Concert," this performance is scheduled on January 31 at 7 pm at the Carlos P. Romulo Auditorium in RCBC Plaza.

Headlining the concert is esteemed Filipino Violinist, Diomedes Saraza, Jr., a distinguished Juilliard graduate and the first Filipino violin soloist to grace Carnegie Hall. Saraza currently serves as the concertmaster of the MSO.

Guiding the orchestra with expertise is guest conductor Olivier Ochanine, the acclaimed winner of the 2015 Antal Dorati International Conducting Competition in Budapest, Hungary. Ochanine is also recognized as the former musical director of the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra, which previously performed at Carnegie Hall alongside Saraza. The event promises to be an exciting and memorable musical experience that will leave concert-goers enthralled.

The repertoire for the evening includes Angel Peña's "Trinity," Carl Nielsen's Symphony No. 1, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto No. 1, all masterpieces poised to elevate the senses and transport the audience to new musical heights.