It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Frank Sinatra - The World We Knew (1967)

Tuesday, January 9, 2024

Aaron Copland - his music and his life

Aaron Copland managed the difficult feat of becoming a popular classical composer while retaining the respect of critics and the ‘serious musical establishment'.

Born in a humble street in Brooklyn, the son of Lithuanian immigrants, Copland is generally regarded as the first indisputably great American composer. The piano came easily to him and, after he’d graduated from the local high school, he had lessons in harmony and counterpoint from the eminent (though conservative) teacher and composer Rubin Goldmark. His first published piece, The Cat and the Mouse, appeared in 1920.

He was able to scrape together enough to go to Paris to study with the doyenne of European teachers, Nadia Boulanger. Here, during his four years at the New School for Americans at Fontainebleau (1921-25), Copland was introduced to an enormous range of musical influences, all of which he was encouraged to absorb: jazz, the neo-classicism of Stravinsky and the whimsicality of Les Six made a particularly strong impression on him and colour the first period of his mature compositions. With a thorough grounding in composition and orchestration under his belt, he returned to America where he became involved in a wide range of musical activities, working as a pianist in a hotel, as a lecturer and as an organiser of various musical societies, as well as composing.

Conductor, publisher and patron of music Serge Koussevitzky became an influential champion of his music throughout his tenure as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, an incalculable boost to Copland’s growing reputation. Between 1930 and 1936 he entered a phase of experimental and dissonant writing (Variations and the Piano Sonata, for instance, are difficult works) before discovering the power of American folk idioms. Here his music is as essentially American as Mussorgky’s or Stravinsky’s is Russian – El Salón México, the ballets Billy the Kid, Rodeo and Appalachian Spring are as American as apple pie. His Lincoln Portrait, using texts from Lincoln’s speeches and letters, has been performed (for better or worse, but generally worse) by world leaders. His patriotic Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) has been used for the opening of every type of formal ceremony. Some of Copland’s film music (The Red Pony, for example, Our Town and Of Mice and Men) is among the most distinguished ever written (he won an Oscar in 1950 for the score of The Heiress). In a nutshell, Copland managed the difficult feat of becoming a popular classical composer while retaining the respect of critics and the ‘serious musical establishment’. In his later works, Copland reverted to serial techniques, writing in a far less approachable, more austere manner.

Whatever one thinks of his virtually unknown middle- and late-period music, Copland has to be admired for his steadfast independence and unwillingness to court popularity for its own sake.

YESTERDAY WHEN I WAS YOUNG - Shirley Bassey (Lyrics)

Franz Lehar- "Gold und Silber",Walzer (Springtime In Vienna 98)

Iosif Ivanovici - Waves of the Danube

Sinead O'Connor died of 'natural causes', UK coroner rules

AT A GLANCE

The Grammy award-winning singer, best known for her 1990 cover of "Nothing Compares 2 U", was found unresponsive at her south London home last July. She was 56.

LONDON (AFP) - Irish musician Sinead O'Connor died last year of "natural causes", a London coroner announced Tuesday.

The Grammy award-winning singer, best known for her 1990 cover of "Nothing Compares 2 U", was found unresponsive at her south London home last July. She was 56.

London police said at the time that officers were not treating it as suspicious as an autopsy was carried out to determine the cause of her death.

A short statement by Southwark Coroner's Court in south London said: "This is to confirm that Ms O'Connor died of natural causes. The coroner has therefore ceased their involvement in her death."

O'Connor's death prompted an outpouring of sympathy from her legions of fans including other musicians and celebrities around the world, particularly in her homeland of Ireland.

Hundreds lined the route of her cortege in Bray, the Irish town 20 kilometres (13 miles) south of Dublin that she called home for 15 years, on the day of her funeral last August.

The willingness of the musician, who rose to international fame in the 1990s, to criticise the Catholic Church in particular saw her vilified by some and praised as a trailblazer by others.

O'Connor's agents revealed she had been completing a new album and planning a tour as well as a movie based on her autobiography "Rememberings" before she died.

The musician had also spoken publicly about her mental health, telling the US television host Oprah Winfrey in 2007 that she struggled with thoughts of suicide and had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

More recently she had shunned the limelight, in particular following the death of her son Shane from suicide in 2022 aged 17.

Monday, January 8, 2024

Carl Michael Ziehrer - Faschingskinder (Waltz / Walzer)

Sunday, January 7, 2024

Yusuf / Cat Stevens – Morning Has Broken (Official Lyric Video)

Lea Salonga and Simon Bowman: The Last Night of the World (1990)

REGINE VELASQUEZ - WRITTEN IN THE SAND - Millennium Y2K

Friday, January 5, 2024

Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1

Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1

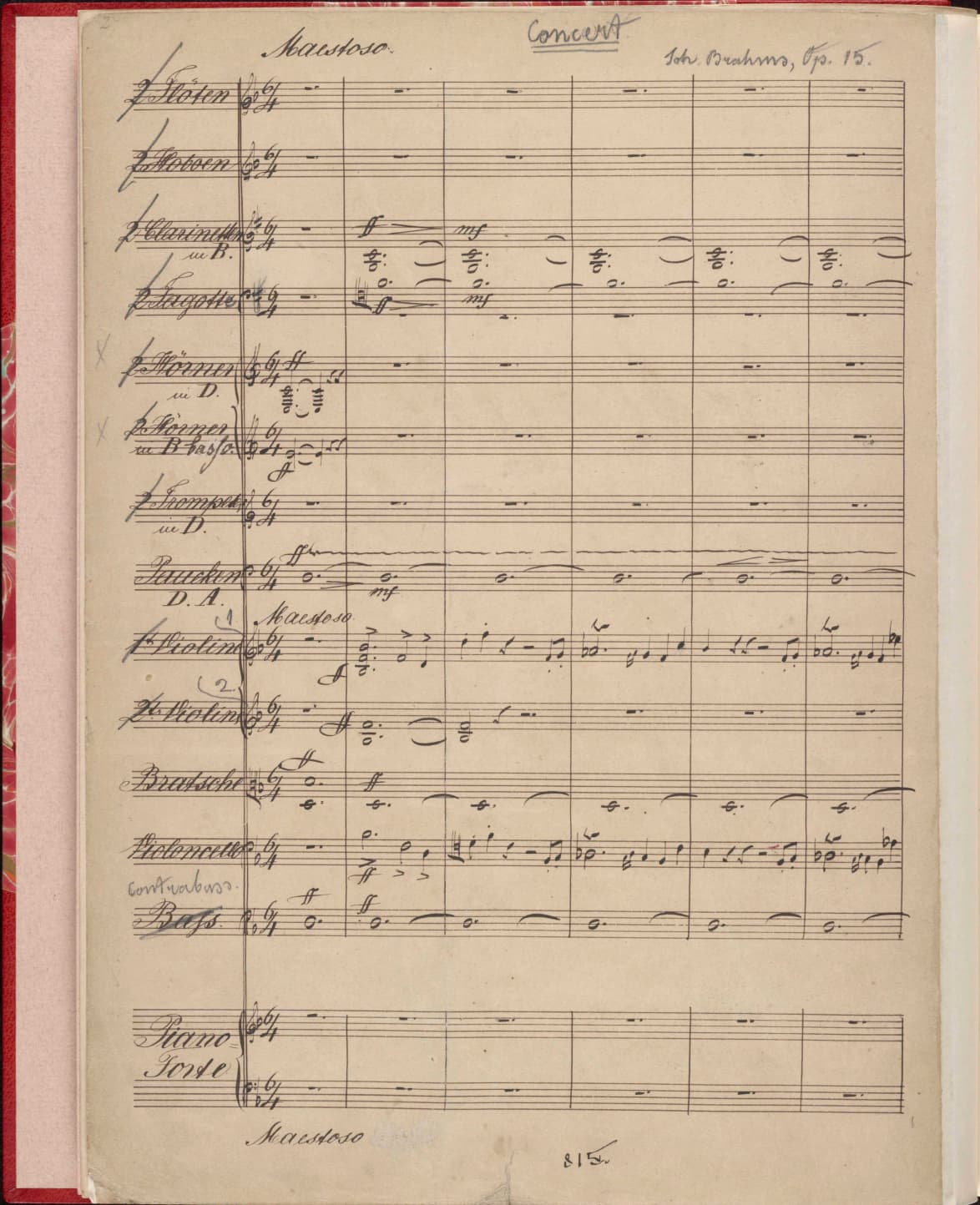

In my previous article I wrote about the Ogdon-Stokowski recording of Brahms’ first piano concerto. Here, I would like to write about the performance of the concerto with consideration to the original score.

Johannes Brahms in 1865

The concerto, Op. 15, was finished in 1857; but it began rather earlier and had taken forms such as a symphony and a double piano sonata before finally becoming a piano concerto. Unfortunately, there were no known surviving copies of the earlier forms as Brahms was very obsessed with destroying draft copies of his own work as well as his compositions that he deemed unworthy.

Driven by curiosity, I decided to look for the manuscript of the concerto. With the direction from the Johannes-Brahms-Gesellschaft (Brahms Society), I located Margrit McCorkle’s book ‘Johannes Brahms: Thematic Bibliographical List of Works’, in the Cambridge University Library, one of the six legal deposit libraries in the U.K. and Ireland. (A legal deposit library houses at least a copy of virtually every book published.) There I found that the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (German State Library in Berlin) keeps the autograph version given by the Joseph-Joachim family in 1917. In fact, it is the only orchestral full score manuscript of the piece (there are two-piano transcriptions). I made an appointment with their Musikabteilung (Music Department) and went to Germany to see the microfiche.

Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 15 copyist’s manuscript © The Morgan Library Museum

There are many very interesting features that can only be revealed by the manuscript. For instance, the way the piano part was written suggested that the staves did not reflect whether the notes should be played by the left hand or the right. There are also places that are different from popular printed version of the piece. One most intriguing observation is the beginning of the second movement, where between the two full-rested piano staves lies a line of writing taken from the Eucharistic Sanctus, Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini, with hyphens between some of the syllables such that the words and the phrasing of the strings agree. At the recapitulation, however, the words do not reappear, nor is the instrumental phrasing the same. It has been suggested that the movement may have been intended for a requiem, or related to Schumann’s death, but there is insufficient evidence linking them together.

In terms of performance practicality, arguably the most significant marking is the metronome marking for the first movement, of 58 to the dotted minim (MM=58), which is not seen in popular editions. Brahms performed the piece himself on multiple occasions, including the rather disastrous premier. As a touring concert pianist, he would likely have sent the orchestral parts ahead of time for the orchestra to rehearse. Therefore, the metronome marking most probably reflects at least the approximate speed that he preferred. Of course, one could always argue that the same Brahms might have preferred a dramatically different tempo on a different day or later in his long career, just as many have observed that Rachmaninoff, who lived well into the recording era, did not follow many of his own markings. Nevertheless, there are other evidences that show, in my opinion, that Brahms’ played his own music considerably faster than recent generations of musicians have been playing.

Brahms at the piano

In Brahms’ days, tempi chosen must have been, ironically, rather faster than they are in the fast-paced modern days. If we consider the tempo MM=58, it would theoretically give the 485 bars (there are only 484 bars in the piece, but two have a time signature of 9/4 instead of 6/4) of the first movement a duration of well under 17 minutes. This is remarkable in that even if we add 30% to this timing to account for agogics, rubato, etc., it will still be considerably faster than many recordings one can find today. In fact, the ducal orchestra of Meiningen, with which Brahms had worked closely, was known to have given concerts with programmes such as Beethoven’s Leonore Overture no. 3 and the seventh symphony, together with Brahms’ first piano concerto and second symphony – all in a single evening. This would have been a pretty long evening if they were played at the tempi common nowadays!

Brahms the conductor also performed the piece. C V Stanford, a pianist who had performed under Brahms’ baton, observed that Brahms conducted the 6/4 as an uneven four-beat. In this way, the beating would agree with a slow-feeling compound duple and give a good deal of lilt. Indeed, in a letter to Clara Schumann, Brahms described the first movement’s 6/4 as ‘slow’. It is not hard to imagine that, for the same tempo to be beaten in six, it would feel uncomfortably fast. I also suspect, given the fact that Brahms was a keen walker, his andante must be fairly brisk too. But did Brahms slow down when he aged?

As his age comes into question and as we are reconstructing the performance practice of Brahms through hints from his manuscript, it is perhaps important to recall that the piece was composed in his early twenties. There is an often overlooked connection between the year of composition and the image of Brahms. It is common to hear people emphasise a rich, substantial bass backed by the argument that Brahms is a big beard, well-sized German, as though he was always so. Although the emphasis itself is most probably correct, as we do know that Brahms favoured orchestras with a large cello and double bass section, the young Brahms in his twenties was thin, kept no beard, and looked almost androgynous. There must be a certain element of youthful energy, enthusiasm, and daringness in Brahms and his music at that age, such that he knocked on Schumann’s door in 1853 unannounced.

Although there may never be answers to how Brahms’ music should be performed definitively (even if Brahms were still alive, there remains the question of which Brahms: Brahms the composer, Brahms the conductor, Brahms the performer, the young Brahms, the aged Brahms…), research into the performance practice of his era and the background of the composition is nonetheless relevant.

Rising Hope: Ralph Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

For the listener on the ground, the song seems to come from nowhere – we’re not in a forest but in open ground. At 100 meters, the little bird is only a dot in the sky.

Skylark (Alauda arvensisO (Photo by Margaret Holland)

This being the bird kingdom, the remarkable ability to hover and sing seems to be one of those sexual tests that nature provides: can hover and sing, therefore in good fitness and good parent material. In real life, a lark’s song can last as long as 20 minutes before it returns to earth to rise again. We don’t hear the melody that Vaughan Williams used – the lark’s song is sweet and piercing but very repetitive.

On the other hand, we’re not the recipients of the lark’s song – that’s for the female lark to interpret.

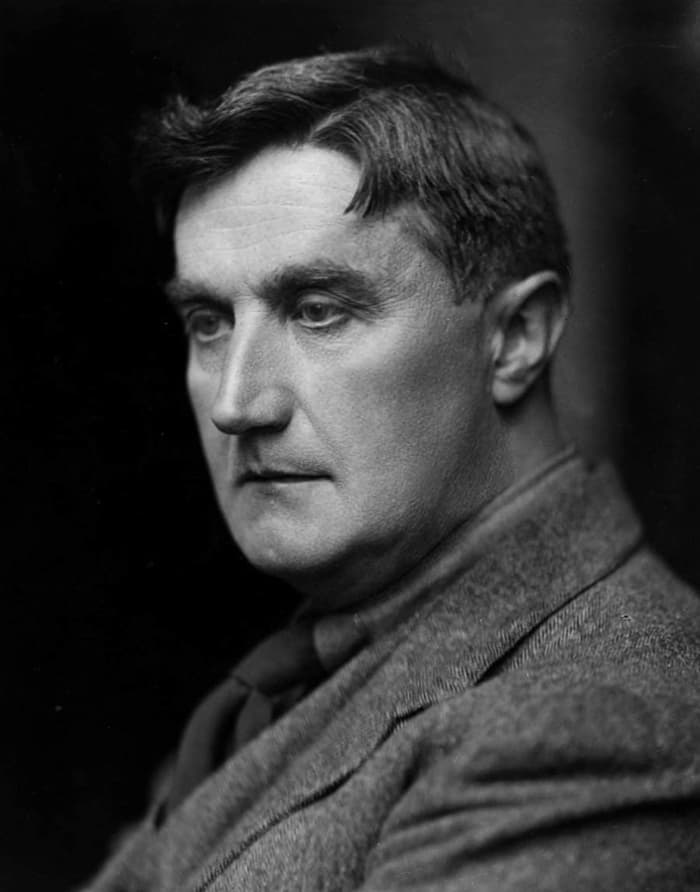

E.O. Hoppé: Vaughan Williams, 1920

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) wrote the first version of his remarkable pastoral romance, The Lark Ascending in the dark days of 1914, first as a version for violin and piano before setting it aside for war service. Returning to composition in 1919, it was the first work he took up, creating the orchestral version. The violin and piano version received its premiere on 15 December 1920, with Marie Hall, the dedicatee, as soloist. She reprised her solo part in the orchestral premiere in London on 14 June 1921. As an occasional piece, it has remained one of the most enjoyable pieces for violin soloists and orchestras of the 20th century.

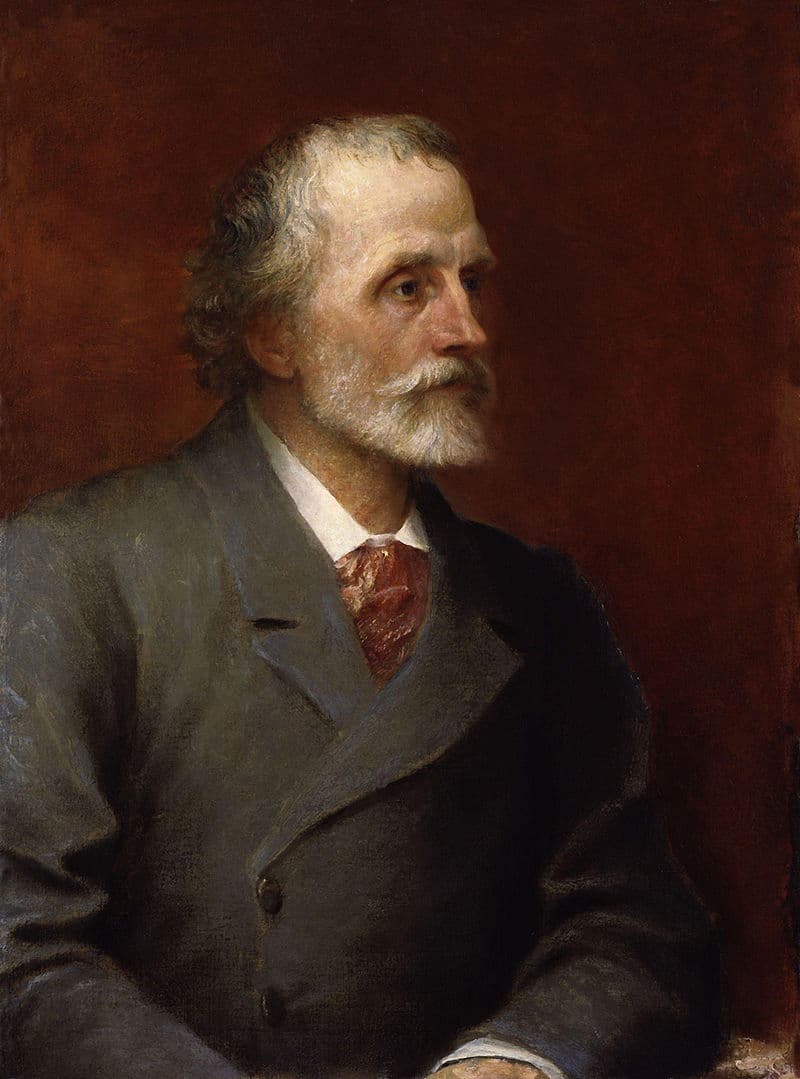

In his manuscript, Vaughan Williams quotes lines from the eponymous poem by George Meredith (1828–1909), taking lines from different sections of the 122-line poem: lines 1–4, 65–70, 77–79, and then the closing couplet.

G.F. Watts: George Meredith, 1893 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake,

…

For singing till his heaven fills,

’T is love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup,

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes:

…

He is, the dance of children, thanks

Of sowers, shout of primrose-banks,

And eye of violets while they breathe;

…

Till lost on his aërial rings

In light, and then the fancy sings.

In those 15 lines, Vaughan Williams gives us his image of the lark, rising into the air and dropping his melody to the earth below. It’s the song of heaven, the love of the earth, and all the hope for tomorrow and tomorrow’s children that are encapsulated in the little bird’s sound.

The work unfolds in one continuous movement, with each new theme introduced and linked by the violinist’s ‘eloquent soliloquies’. In the end, the violin returns to its opening phrases, and the sound drops away, ‘lost on his aerial rings’ as he flies higher and higher.

Meredith describes the song as linking ‘chirrup, whistle, slur and shake’ in an unbroken line. Yet it’s all the other elements that contribute to the effectiveness of Vaughan Williams’ setting: the calmness of the scene, the contented happiness of the lark, and the prospect of only good.

Why do we hear this as not only a song of nature but also as one of hope? The bird must sing his song and never knows on whose ears it will fall. When it falls on ours, we can only look up in awe at this sound descending from the sky above. It draws us up into the lark’s world, and in Vaughan Williams’ setting, which creates melody from just suggestions from the bird, we are carried on wings of song to a better tomorrow.