Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1

In my previous article I wrote about the Ogdon-Stokowski recording of Brahms’ first piano concerto. Here, I would like to write about the performance of the concerto with consideration to the original score.

Johannes Brahms in 1865

The concerto, Op. 15, was finished in 1857; but it began rather earlier and had taken forms such as a symphony and a double piano sonata before finally becoming a piano concerto. Unfortunately, there were no known surviving copies of the earlier forms as Brahms was very obsessed with destroying draft copies of his own work as well as his compositions that he deemed unworthy.

Driven by curiosity, I decided to look for the manuscript of the concerto. With the direction from the Johannes-Brahms-Gesellschaft (Brahms Society), I located Margrit McCorkle’s book ‘Johannes Brahms: Thematic Bibliographical List of Works’, in the Cambridge University Library, one of the six legal deposit libraries in the U.K. and Ireland. (A legal deposit library houses at least a copy of virtually every book published.) There I found that the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (German State Library in Berlin) keeps the autograph version given by the Joseph-Joachim family in 1917. In fact, it is the only orchestral full score manuscript of the piece (there are two-piano transcriptions). I made an appointment with their Musikabteilung (Music Department) and went to Germany to see the microfiche.

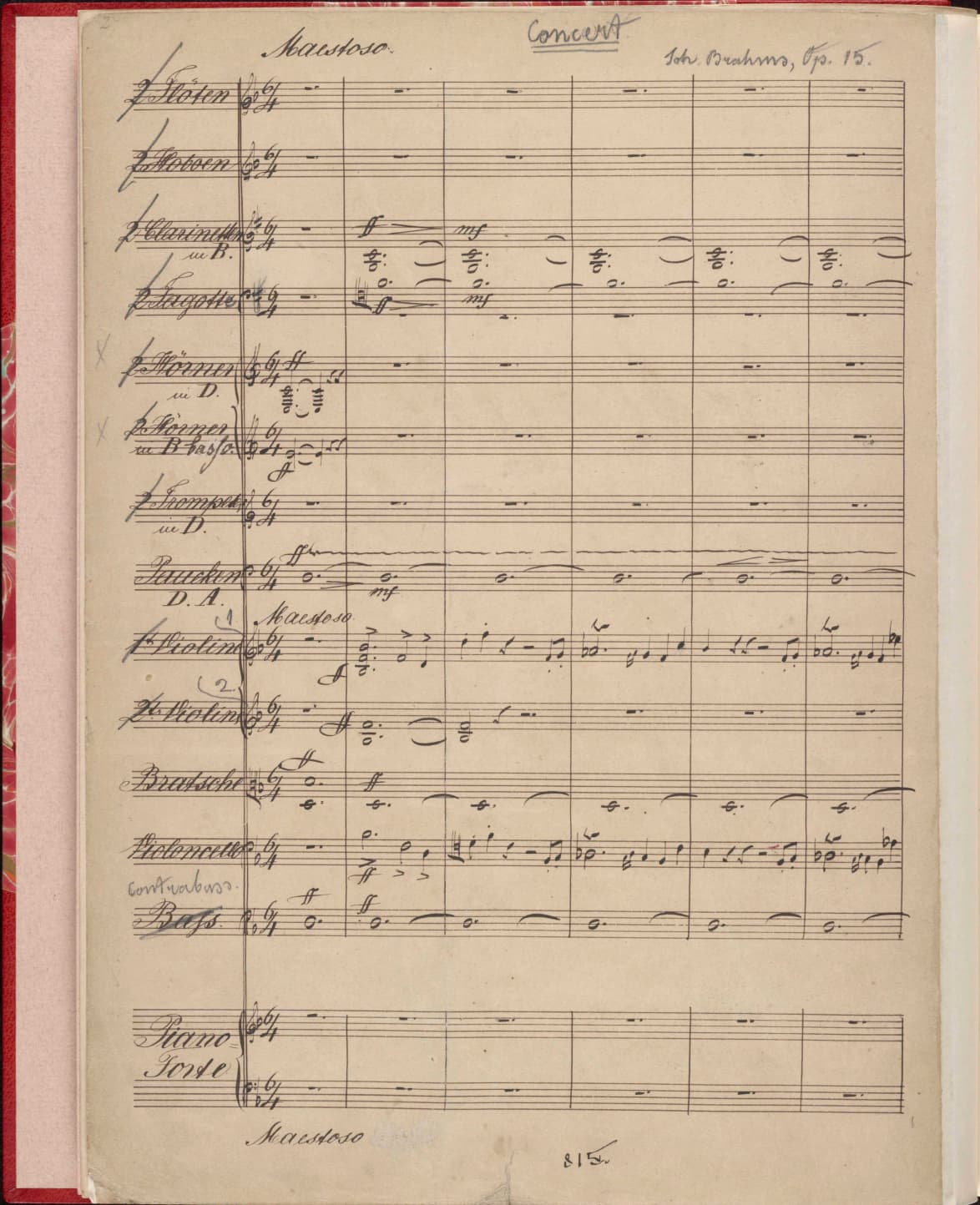

Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 15 copyist’s manuscript © The Morgan Library Museum

There are many very interesting features that can only be revealed by the manuscript. For instance, the way the piano part was written suggested that the staves did not reflect whether the notes should be played by the left hand or the right. There are also places that are different from popular printed version of the piece. One most intriguing observation is the beginning of the second movement, where between the two full-rested piano staves lies a line of writing taken from the Eucharistic Sanctus, Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini, with hyphens between some of the syllables such that the words and the phrasing of the strings agree. At the recapitulation, however, the words do not reappear, nor is the instrumental phrasing the same. It has been suggested that the movement may have been intended for a requiem, or related to Schumann’s death, but there is insufficient evidence linking them together.

In terms of performance practicality, arguably the most significant marking is the metronome marking for the first movement, of 58 to the dotted minim (MM=58), which is not seen in popular editions. Brahms performed the piece himself on multiple occasions, including the rather disastrous premier. As a touring concert pianist, he would likely have sent the orchestral parts ahead of time for the orchestra to rehearse. Therefore, the metronome marking most probably reflects at least the approximate speed that he preferred. Of course, one could always argue that the same Brahms might have preferred a dramatically different tempo on a different day or later in his long career, just as many have observed that Rachmaninoff, who lived well into the recording era, did not follow many of his own markings. Nevertheless, there are other evidences that show, in my opinion, that Brahms’ played his own music considerably faster than recent generations of musicians have been playing.

Brahms at the piano

In Brahms’ days, tempi chosen must have been, ironically, rather faster than they are in the fast-paced modern days. If we consider the tempo MM=58, it would theoretically give the 485 bars (there are only 484 bars in the piece, but two have a time signature of 9/4 instead of 6/4) of the first movement a duration of well under 17 minutes. This is remarkable in that even if we add 30% to this timing to account for agogics, rubato, etc., it will still be considerably faster than many recordings one can find today. In fact, the ducal orchestra of Meiningen, with which Brahms had worked closely, was known to have given concerts with programmes such as Beethoven’s Leonore Overture no. 3 and the seventh symphony, together with Brahms’ first piano concerto and second symphony – all in a single evening. This would have been a pretty long evening if they were played at the tempi common nowadays!

Brahms the conductor also performed the piece. C V Stanford, a pianist who had performed under Brahms’ baton, observed that Brahms conducted the 6/4 as an uneven four-beat. In this way, the beating would agree with a slow-feeling compound duple and give a good deal of lilt. Indeed, in a letter to Clara Schumann, Brahms described the first movement’s 6/4 as ‘slow’. It is not hard to imagine that, for the same tempo to be beaten in six, it would feel uncomfortably fast. I also suspect, given the fact that Brahms was a keen walker, his andante must be fairly brisk too. But did Brahms slow down when he aged?

As his age comes into question and as we are reconstructing the performance practice of Brahms through hints from his manuscript, it is perhaps important to recall that the piece was composed in his early twenties. There is an often overlooked connection between the year of composition and the image of Brahms. It is common to hear people emphasise a rich, substantial bass backed by the argument that Brahms is a big beard, well-sized German, as though he was always so. Although the emphasis itself is most probably correct, as we do know that Brahms favoured orchestras with a large cello and double bass section, the young Brahms in his twenties was thin, kept no beard, and looked almost androgynous. There must be a certain element of youthful energy, enthusiasm, and daringness in Brahms and his music at that age, such that he knocked on Schumann’s door in 1853 unannounced.

Although there may never be answers to how Brahms’ music should be performed definitively (even if Brahms were still alive, there remains the question of which Brahms: Brahms the composer, Brahms the conductor, Brahms the performer, the young Brahms, the aged Brahms…), research into the performance practice of his era and the background of the composition is nonetheless relevant.