by Maureen Buja, Interlude

For the listener on the ground, the song seems to come from nowhere – we’re not in a forest but in open ground. At 100 meters, the little bird is only a dot in the sky.

Skylark (Alauda arvensisO (Photo by Margaret Holland)

This being the bird kingdom, the remarkable ability to hover and sing seems to be one of those sexual tests that nature provides: can hover and sing, therefore in good fitness and good parent material. In real life, a lark’s song can last as long as 20 minutes before it returns to earth to rise again. We don’t hear the melody that Vaughan Williams used – the lark’s song is sweet and piercing but very repetitive.

On the other hand, we’re not the recipients of the lark’s song – that’s for the female lark to interpret.

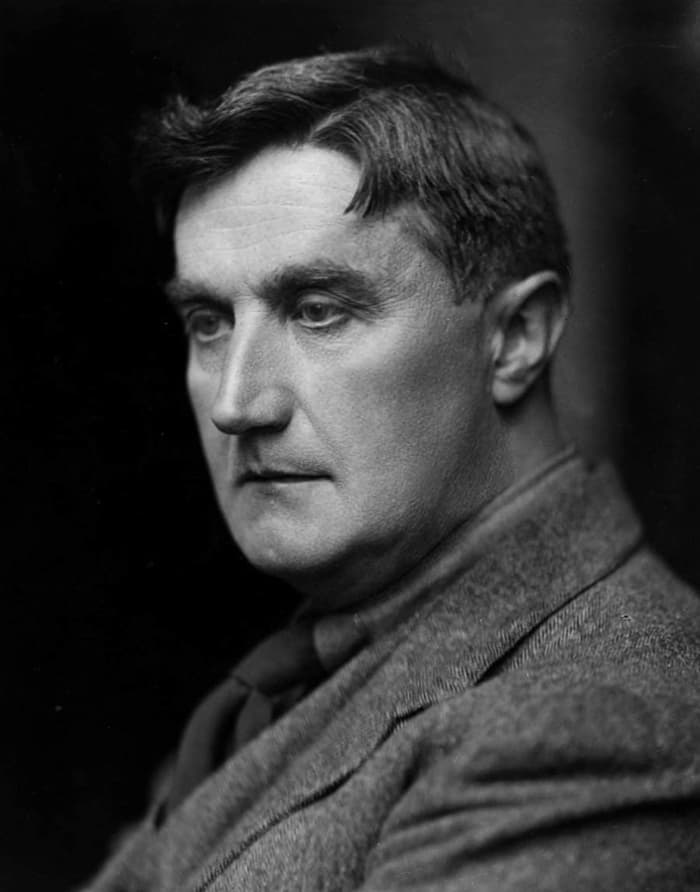

E.O. Hoppé: Vaughan Williams, 1920

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) wrote the first version of his remarkable pastoral romance, The Lark Ascending in the dark days of 1914, first as a version for violin and piano before setting it aside for war service. Returning to composition in 1919, it was the first work he took up, creating the orchestral version. The violin and piano version received its premiere on 15 December 1920, with Marie Hall, the dedicatee, as soloist. She reprised her solo part in the orchestral premiere in London on 14 June 1921. As an occasional piece, it has remained one of the most enjoyable pieces for violin soloists and orchestras of the 20th century.

In his manuscript, Vaughan Williams quotes lines from the eponymous poem by George Meredith (1828–1909), taking lines from different sections of the 122-line poem: lines 1–4, 65–70, 77–79, and then the closing couplet.

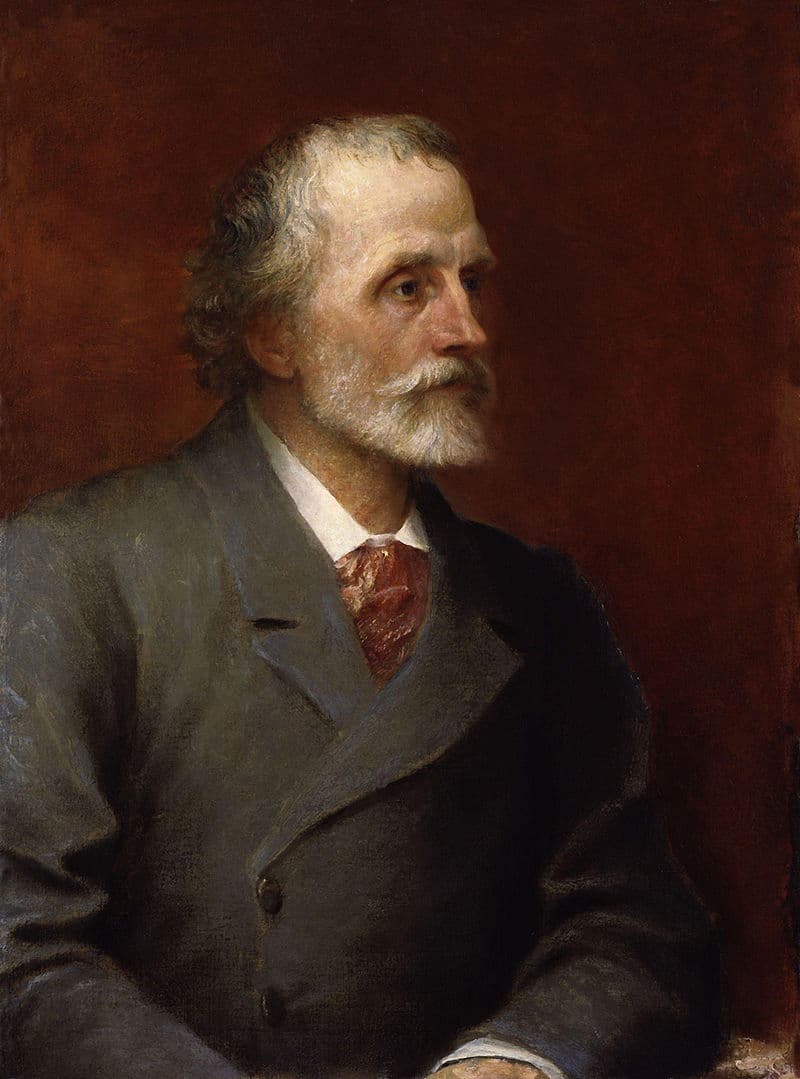

G.F. Watts: George Meredith, 1893 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake,

…

For singing till his heaven fills,

’T is love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup,

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes:

…

He is, the dance of children, thanks

Of sowers, shout of primrose-banks,

And eye of violets while they breathe;

…

Till lost on his aërial rings

In light, and then the fancy sings.

In those 15 lines, Vaughan Williams gives us his image of the lark, rising into the air and dropping his melody to the earth below. It’s the song of heaven, the love of the earth, and all the hope for tomorrow and tomorrow’s children that are encapsulated in the little bird’s sound.

The work unfolds in one continuous movement, with each new theme introduced and linked by the violinist’s ‘eloquent soliloquies’. In the end, the violin returns to its opening phrases, and the sound drops away, ‘lost on his aerial rings’ as he flies higher and higher.

Meredith describes the song as linking ‘chirrup, whistle, slur and shake’ in an unbroken line. Yet it’s all the other elements that contribute to the effectiveness of Vaughan Williams’ setting: the calmness of the scene, the contented happiness of the lark, and the prospect of only good.

Why do we hear this as not only a song of nature but also as one of hope? The bird must sing his song and never knows on whose ears it will fall. When it falls on ours, we can only look up in awe at this sound descending from the sky above. It draws us up into the lark’s world, and in Vaughan Williams’ setting, which creates melody from just suggestions from the bird, we are carried on wings of song to a better tomorrow.

No comments:

Post a Comment