It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Thursday, January 6, 2022

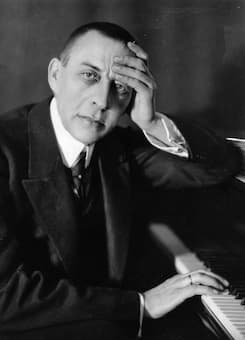

Serge Rachmaninoff - his music and his life

Tuesday, January 4, 2022

Leningrad Does Varietee: Wooding, Shostakovich, Dunayesky and Prokofiev

by Georg Predota , Interlude

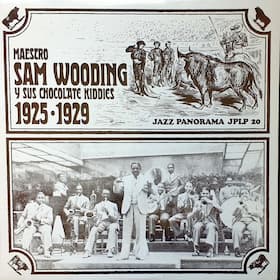

Sam Wooding and his Chocolate Kiddies

Just a couple of years after Western Europe fell under the spell of popular American musical styles, it also debuted in the Soviet Union. As a musical language increasingly placed at the service of social commentary, and with its strong connotations for freedom, jazz in the Soviet era led a somewhat tortured existence. Constantly in flux between prohibition, censorship and even state sponsorship, jazz developed into a popular form of music and it became an element of Soviet cultural life. The birth of Soviet jazz is celebrated on 1 October 1922 when Valentin Parnach and his band played their first concert in Moscow.

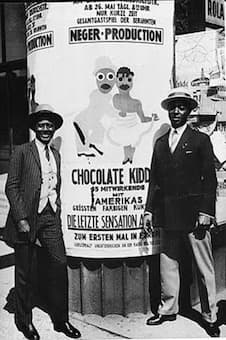

Chocolate Kiddies poster

Parnach came into contact with jazz at a concert of the American band Louis Mitchel Jazz Kings during his exile in Paris in 1921. He returned to Moscow a year later with a complete set of instruments. But what really got the jazz craze properly started were appearances of bandleader Sam Wooding and his “Chocolate Kiddies.” Essentially a Broadway-styled revue billed as a “negro operetta,” it toured the Soviet Union in 1926 for three months with appearances in Moscow and Leningrad. Joseph Stalin was in the Moscow audience, and criticism focused on the visual aspects of the performance. As a reviewer wrote, “it is not important how blacks play, how they dance, sing and think… What is important is that they are all black.”

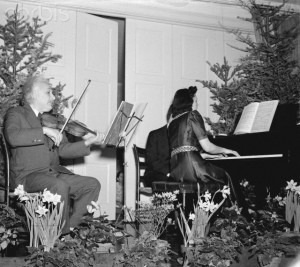

Sam Wooding & his Chocolate Kiddies in Leningrad

Dmitri Shostakovich

When the Chocolate Kiddies Company arrived in Leningrad, a highly interested Dmitri Shostakovich sat in the audience. According to musicologists, this “was, to Shostakovich a musical revelation of America.” Growing up in the young Leninist Soviet Union, Shostakovich had previously only gleaned jazz through selected friends and sparse historical information. The vitality and enthusiasm of the performers made an indelible impression, and jazz remained part of his compositional toolkit. Political circumstances beyond his control made it impossible to overtly practise his appreciation, but in 1934 he was commissioned by a Leningrad dance band to furnish some dancing music. The resulting Suite for Jazz Orchestra is a whimsical take on jazz, reflecting more of the composer’s interest in gypsy music and the music of the Yiddish theatre. As such, we expectedly find a waltz and a polka, but it also features a concluding foxtrot. Conforming to severe Soviet guidelines, this jazz suite leaves no room for improvisation but unfolds in strict time and rhythm.

May Day in Leningrad (1925)

The Soviet Union experienced massive political and economic upheavals in the early 1930s, and jazz was eyed as an undesirable import of Western culture. Joseph Stalin tightly controlled all manner of artistic expression, and he demanded that all forms of art convey the struggles and triumphs of the proletariat and present a realistic reflection of Soviet life and society. Searching for a musical style “in which the ideology of the emerging communist communal society could be expressed most effectively” also meant that jazz had to be politicized.

Isaak Dunayesky

Maxim Gorki, writing during his exile in Sorrento, equated jazz with homosexuality, drugs and eroticism. He describes jazz as “a dry knock of an idiotic hammer penetrates the utter stillness. One, two, three, ten, twenty strikes, and afterwards a wild whistling and squeaking as if a ball of mud was falling into clear water; then follows a rattling, howling and screaming like the clamor of a metal pig, the cry of a donkey or the amorous croaking of a monstrous frog. The offensive chaos of this insanity combines into a pulsing rhythm. Listen to this screaming for only a few minutes, and one involuntarily pictures an orchestra of sexually wound-up madmen, conducted by a Stallion-like creature who is swinging his giant genitals.” The alleged connection between jazz, modern dance and sexuality was officially classified as “sonic idiocy in the bourgeois-capitalist world.” Given such overt hostility, jazz idioms found refuge in motion pictures.

Sergei Prokofiev

With Soviet artists and performers increasingly falling under the microscope of uncompromising state machinery, Sergei Prokofiev—with permission from the government—packed his bags and settled in Paris in October 1923. In a city awash with artistic personalities, Prokofiev quickly became interested in jazz and rubbed shoulders with leading composers, including George Gershwin in 1928. Vernon Duke reports, “George came and played his head off; Prokofiev liked the tunes and the flavoursome embellishments, but thought little of the Concerto in F, which he said later, consisted of “32-bar choruses ineptly bridged together.” Prokofiev thought highly of Gershwin’s gifts, both as a composer and pianist, and he predicted “he’d go far should he leave dollars and dinners alone.” Duke also remembered Prokofiev saying, “Gershwin’s piano playing is full of amusing tricks, but the music is amateurish.” Prokofiev met Gershwin again in 1930 in New York, and noted in his journal afterward, “Gershwin also attempts to compose serious music, and sometimes he even does that with a certain flair, but not always successfully.” For all the criticism and posturing, it is clear that Prokofiev was highly receptive to jazz influences. One might actually describe the slow movement of his Third Piano Concerto, a work that had been started as far back as 1913, as greatly indebted to Gershwin.

Beethoven and Money

by Georg Predota , Interlude

For much of his career and life, Beethoven was struggling financially. He would on occasion make a shedload of money, which he tended to invest in bank shares. However, the severe depreciation of the Austrian currency as a result of the extended Napoleonic war, slashed his wealth by over fifty percent, and it also significantly reduced the value of the annuity paid to him by Archduke Rudolph, and the Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky. And even when Beethoven was relieved from any rational grounds for financial worry, he was constantly apprehensive about his financial situation.

For much of his career and life, Beethoven was struggling financially. He would on occasion make a shedload of money, which he tended to invest in bank shares. However, the severe depreciation of the Austrian currency as a result of the extended Napoleonic war, slashed his wealth by over fifty percent, and it also significantly reduced the value of the annuity paid to him by Archduke Rudolph, and the Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky. And even when Beethoven was relieved from any rational grounds for financial worry, he was constantly apprehensive about his financial situation.

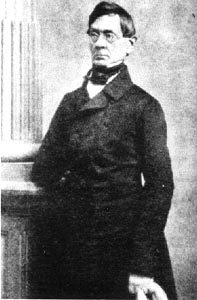

Beethoven, 1803

To make a living as a freelance musician is no easy task and during his early days in Vienna Beethoven established a reputation as a piano virtuoso. But what is more, his ability to improvise was legendary. Most of his income during his early years in Vienna was earned by performing in salons. Only later was he able to charge admission to public concerts of his music, and in his 34 years in Vienna Beethoven was paid for performing in only fifteen public concerts. However, Vienna initially had attracted pianists and musicians from all parts of the Continent, and it took a bit of time to work through the intrigues and jealousies of his contemporaries and rivals. Cherubini, for example, described Beethoven’s piano style as “rough,” and the man himself as “an unlicked bear cub.” In the end, Beethoven became all the rage and was capable of commanding large sums for his performances. Sadly, as his hearing diminished, this particular revenue stream would close for good.

Giulietta Guicciardi

To supplement his income, Beethoven would give private lessons, an activity he absolutely hated. He clearly was not temperamentally suited for such pedagogical pursuits, and a colorful anecdote relates that be became so enraged by his student Karl Hirsch that he “bit him on the shoulder.” Apparently he also pinched the unfortunate child, and yelled at him incessantly in great rage. He would, however, accept charming young countesses as students, but in accordance with some outdated tradition and his desire to be viewed as part of the upper classes, often refused to accept money for his services. When the Countess Susanne Guicciardi sent him a gift for instructing her daughter Giulietta, Beethoven wrote, “I think you should know, dearest countess, that you would have received your present back yesterday morning almost on the spot if my brother hadn’t happened to be with me… But now for my warning. I accept this present, but should it ever occur to you to let yourself think up anything even remotely similar, I swear by everything that I hold sacred that you will never see me again in your house. Your greatly upset Beethoven.” Well, today we know all about Beethoven’s feelings for Giulietta, but with his loss of hearing, he was no longer able to provide teaching services as well.

Brief Beethoven an Breitkopf & Härtel, 9. Oktober 1811 (BG 523)

Once Beethoven had turned his attention to composition, he would of course receive payments for commissions. This generally involved some kind of cash advance for the composer, and upon completion, the patron was given exclusive performing right for six months. After that, the patron kept the music but Beethoven could sell it for publication. Recent scholarship has described Beethoven as an unscrupulous businessman, but in some respects he seems to have been simply incompetent, as the commissions for even his greatest works barely sufficed to make a living. Beethoven received the pittance of 500 florins from Count Franz Oppersdorf for his 4th Symphony. Oppersdorf was delighted and offered another 500 florins for an additional symphony. That put Beethoven in a bind, as he had previously promised the 4th Symphony to the publisher Breitkopf. He hastily wrote to Breitkopf explaining “a gentleman of quality has taken it from me.” He then sold the symphony he promised, and for which he had already received a cash advance from Oppersdorf, to Breitkopf. His Fifth Symphony went to Breitkopf for 100 ducats, about 450 florins, and Oppersdorf rightly refused to pay his balance. With dealings like that, it is not surprising that Beethoven was unable to maintain his own apartment, and for a time he had to move in with Countess von Erdödy.

Anton Schindler

The business of music publishing changed rapidly during Beethoven’s lifetime, and he essentially “lived as a modern composer on earnings from his work in a free market.” Music publishers were opening businesses all across Germany and Austria, but they still lagged behind England, Italy and France. With the concepts of royalties and international copyrights essentially unknown, the composer could expect a one-time fee for the sale of a work. The publisher in turn had some kind of protection within his own country, but it could still be freely copied and pirated abroad. And pirates dominated the publishing business, as they stole music, “altered it, misattributed it, bribed copyists to steal it, and pasted their own name over copies bought from the original publishers.”

Within this seriously messy environment, Beethoven’s principle aim was to obtain the largest sum possible for each composition, and he compared offers from various publishers, and on occasion, played them against each other. Beethoven, in following the example set by Joseph Haydn, was clearly interested in publishing a work simultaneously in more than one country. That way, he would receive two or more fees and was able to make his works more attractive by charging lower fees from each publisher. Publishers predictably protested vigorously, and so did Beethoven. Beethoven was no pioneering businessman, but he did succeed in publishing a fair number of his compositions by two or more firms in different countries at about the same time. It is possible that the early Beethoven biographer Anton Schindler most aptly summarized Beethoven’s money and business dealings in a motto inscription on the autograph manuscript of the Op. 129 “Rondo alla ingharese quasi un capriccio.” He tellingly wrote “Rage over a lost Penny, vented in a Caprice.”

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

Muses and Musings - Bettina Brentano: Everybody’s Muse!

by Georg Predota , Interlude

Bettina Brentano

© Wikipedia

She aroused the curiosity of Napoleon Bonaparte and went for intimate walks with Karl Marx. She entertained a significant passion for Goethe, who deflected her craving into an extended correspondence and companionship, and she was Beethoven’s muse. Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms dedicated songs to her, and the Grimm brothers devoted an edition of their fairy tales to her. Who was this incredible woman? Her name was Elisabeth Brentano, better known as Bettina. She was the sister of the famous poet Clemens Brentano, and the wife to another, Achim von Arnim, whom she bore 11 children. She never wrote poetry but her writings outraged and fascinated people, and she also composed music. Her first two songs appeared under the pseudonym “Beans Beor” (blessing, I am blessed). Approaching composition from a literary viewpoint, a number of her songs were published during her lifetime. Young virtuosos and composers like Franz Liszt, Joseph Joachim, Peter Cornelius and Johann Kinkel admired her as a friend of Goethe and Beethoven, and her influence on young musicians was of lasting importance. She was “a supreme muse, a one-woman literary movement, at once among the singular and most representative figures of the Romantic century.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

© travel-target.com

Bettina was born in Frankfurt in 1785, and her mother had been Goethe’s first love. When she died, Bettina was sent to the convent, and eventually her mad brother Clemens—at some point he had painted his entire room, floor to ceiling, including the carpet, curtains, furniture, and his own face blue—became her mentor. Clemens and his friend Achim von Arnim, with substantial help from Bettina, collected folk poems, which they eventually published as the seminal work of German Romanticism, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Bettina had always been a rebel, and her first love was a girl five years her senior whom she met in the convent. When she was 21, she was introduced to Goethe, and when he asked what interested her, she replied “Nothing interests me but you.” Apparently, “she leapt into his lap, threw her arms around his neck and went to sleep.” She clearly wanted to be his muse, maybe more. She wrote in a letter, “I have been jealous and sometimes I have felt myself to be the subject of your poems – and why shouldn’t I dream myself into happiness? What higher reality is there than dream?” Goethe, over 30 years her senior, did not know how to handle her, so he turned her letters into the materials for his books and poem, “but he kept her at arm’s length.”

© sueyounghistories.com

By 1810, Bettina had made herself known to another great artist of her age, Ludwig van Beethoven. According to her own recollections, “one day as Beethoven was working at the piano, I placed my hands on his shoulders. He turned in anger to find an attractive young woman who spoke melodiously in his ear: My name is Brentano.” Seemingly, Beethoven was enchanted by her forthright manner, and they developed a close friendship but were never lovers. She certainly was determined to bring Goethe and Beethoven together, which eventually happened in a single rather uneasy meeting. In her letters she kept quoting Beethoven and Goethe, but all the words were her own invention! Admirers suggest that Bettina created her own literary genre, the “epistolary novel.”

Bettina’s influence was felt throughout central Europe, and that included support for Johanna Kinkel, the female composer, writer, pianist and music teacher who published about 70 songs for voice and piano. Escaping from an abusive husband, Johann lived with Bettina von Arnim for several months, and helped her with compositions and translation projects. Her first collection of six songs, published under the name “J. Mathieux” is dedicated to her mentor, and the critic Ludwig Rellstab suggested, “She would soon become respected and well known.” Bettina tirelessly campaigned against anti-Semitism, wrote some seriously dangerous political books demanding liberalization of Prussian rule, and was even branded a communist. Her last book, Conversations with Demons almost ruined her financially, and looking at a bust of Goethe she died in her bed at 74. Scholars and critics agree that Bettina von Arnim was unique in a century rich with extravagant characters. “She was everyone’s muse, she craved love from every quarter, but she was never other than her own person. Her greatest creation was herself!”

Thursday, December 23, 2021

The Composer’s Block

by Doug Thomas, Interlude

Is the writer’s block (or composer’s block) avoidable? © Goalcast

Being stuck in front of an empty page is quite a common phenomenon for artists, regardless of the medium or format of the art. The writer’s block is the result of the creator not being able to produce new works, and unfortunately it can last for years. It is not only measured by the time elapsed without creating, but also by the productivity over time. A disease that all artists avoid like a plague, yet as much as one can try to steer away from being left with no inspiration, it is at times unavoidable. Some composers have made it a strength, an opportunity to reset, while some have suffered from it forever.

Is the writer’s block — or in this case, the composer’s block — avoidable? If so, how does one avoid the blank page as it is also known?

Sergei Rachmaninoff © euroarts.com

One of the most famous composers who has suffered from the blank page is of course well-knowingly Rachmaninoff, whose three yearlong depression resulted in a writer’s block, leaving the Russian composer unproductive for a long time. He is not the only composer though, Schubert faced difficulty in composing too when he became ill and depressed towards the end of his short life, and even Beethoven faced a few years of creative block, composing less than ten works for almost seven years!

There are a few ways around the writer’s block. Mozart, and many of his peers — despite having a very fertile brain — always composed following pre-set structures – including the harmonic structure — and all that was left to do was fill in the blanks with melodic material. Composing by numbers as one could call it!

Of course, the more one composes, the more the juices flow. When composing as a duty — in the case of Bach for instance — it is a lot easier to be more tolerant as well as detached from emotional and intellectual opinions, creative ideas are more easily accepted. The work has to eventually be completed! Creativity is like a muscle, it needs daily exercise.

Gardens Of The Villa Deste At Tivoli By Jean Baptiste Camille Corot

© Crescendo Magazine

One can use pre-existing material to plant the seed for inspiration, as does Nyman in his own interpretation of Mozart’s Don Giovanni in his In Re Don Giovanni. But the source does not necessarily require an existent musicality; other artistic works — in literature, painting — or even life experiences, such as travels, can provide a great source of inspiration. Think of Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage, where the landscapes and cityscapes of Italy and Switzerland provide the canvas to the Hungarian composer’s masterpiece.

Eventually, another fantastic way to release the inspiration is of course to think outside of the box; compose for unusual instruments, unexpected settings, or in the case of Cage compose without composing; “4’33”, despite not containing a single note of music, it is one of the most inspired piece of work ever composed.

Some composers seem to have never been affected by the writer’s block and some others are well-known for having benefited from a lack of ideas to express, like Pärt — whose pause and return to music allowed him to come back with his true voice and expression and signature Tintinnabuli style. Outside of the music world, Frank Zappa or Bob Dylan are great examples of musicians whose regular and constant output allowed them not to ever feel the symptoms of the blank page.

One never quite runs out of ideas, rather one forgets how to find and reach them. Creativity is a stew which develops flavours over time and needs constant stirring and heat in order to express itself. The responsibility of the composer is as much to maintain his creativity boiling as to create.

The most adventurous composers rarely suffer from the writer’s block. It is rather for the ones that take shortcuts in their creativity, relying too much on their past achievements and waiting for external triggers to enable it to emerge.

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Camille Saint-Saëns - His Music and His Life

Camille Saint-Saëns in 1900

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was one of the leaders of the French musical renaissance during the later part of the 19th century. He was a scholar of music history and tolerant of a wide range of musical issues and directions. He tellingly wrote: “I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it; one cannot make over one’s personality.” His views on expression and passion in art conflicted with a prevailing Romantic aesthetic that was engulfed by Wagnerian influences.

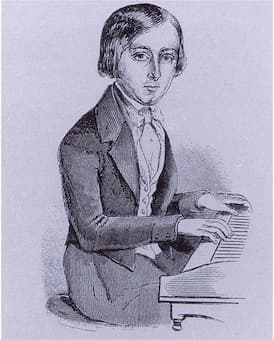

Camille Saint-Saëns, 1846

In his memoirs he wrote, “Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” Saint-Saëns possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness and productivity was compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Yet, during a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and by the time of his death on 16 December 1921, his compositional style was considered deliberately old fashioned. Scathing critical opinion suggested “Saint-Saëns has written more rubbish than any one I can think of. It is the worst, most rubbishy kind of rubbish.”

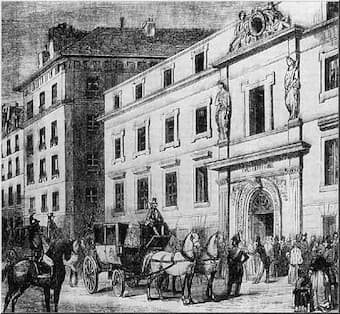

Saint Merri Church in Paris

Saint-Saëns was born in the Rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement of Paris on 9 October 1835. Two months after the christening, his father died of consumption and young Camille was taken to the country. “It is not generally realized,” a music critic wrote, “that Saint-Saëns was the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart.” He produced his first composition at age 3, and publically performed a Beethoven violin sonata at age 4. Saint-Saëns made his official public debut at the Salle Pleyel at the age of ten, performing piano concertos by Mozart and Beethoven. An anecdote tells that he offered to play as an encore any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory. Hector Berlioz admiringly wrote, “This young man knows everything, and he is an absolutely shattering master pianist,” with Franz Liszt declared him “the world’s greatest organist.” In addition to his musical prowess, Saint-Saëns excelled in his academic studies. He distinguished himself in the study of French literature, Latin, Greek, and Divinity. He acquired a taste for mathematics and the natural sciences, including archaeology, astronomy and philosophy. At the age of thirteen, Saint-Saëns was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire where he specialized in organ studies and took formal courses in composition.

The old Conservatoire de Paris, early 19th century

Saint-Saëns competed for the Prix de Rome in 1852, but the award went to Léonce Cohen instead. Upon graduation from the Conservatoire, Saint-Saëns accepted the organist post at Saint-Merri, and by 1858 he was appointed organist of La Madeleine, the official church of the Empire. Saint-Saëns became a teacher at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse and he counted Fauré, Messager and Gigout among his most prominent students. Although he supported and promoted the music of Liszt, Schumann, and Wagner, Saint-Saëns wrote, “I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion.” Going against the grain of French musical life in the mid-19th century, his main love was instrumental music. Extraordinarily active in the field of chamber music, not only as a composer but also as a performer, he might rightfully be considered one of the pioneers of French chamber music. Saint-Saëns left his teaching position in 1865 and pursued a career as a performer and composer.

Saint-Saëns at the piano for his planned farewell concert in 1913,

conducted by Pierre Monteux

Saint-Saëns was an excellent craftsman with a fine sense of musical style, and he placed his talents into the services of the Société Nationale de Musique. He wrote important articles in support of performing music by living French composers, and embarked on a number of operatic projects. His opera Le timbre d’argent had its première at the Théâtre Lyrique in 1877, and he scored a solid success with Samson et Dalila, a work that kept a foothold on the international stage. Saint-Saëns was elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1881, and he was made an officier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1884. Always a keen traveler, Saint-Saëns made 179 trips to 27 countries between 1870 and the end of his life. Avoiding Parisian winter, Saint-Saëns spent substantial portions of the year in Algiers and various places in Egypt. He resigned from the Société Nationale in 1886, and although his popularity in France began to wane, he was still regarded as the greatest living French composer in America and England.

Interior of Saint-Saëns’ tomb in Montparnasse

Saint-Saëns performed his last concert on 6 August 1921, and concluded his conducting career shortly thereafter. He died of a heart attack on 16 December 1921 in Algiers, and his body was taken back to Paris for a state funeral at the Madeleine. During a period immersed in modernism of all kinds, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and his steadfast dedication to musical moderation, clarity, balance and precision deservedly earned him the nickname “French Beethoven.” Contemporary critics, on the other hand, polemically called him “the greatest composer without talent.” From the perspective of music history, however, we now understand that Saint-Saëns compositional approach, deeply inspired by French classicism, was an important forerunner of the neoclassicism practices of Ravel and others.

E=Mozart2: Albert Einstein and Music

by Georg Predota , Interlude

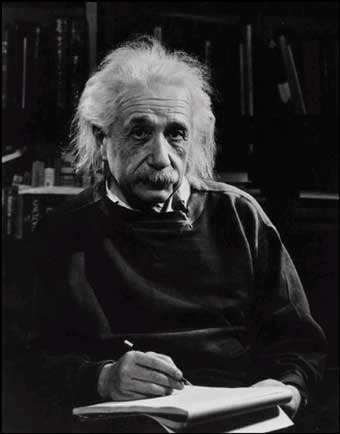

Albert Einstein in 1947 © biography4u.com

The German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1925 for his work in quantum mechanics, suggested “The space in which a person developed as an intellectual/spiritual being has more dimensions than the space which he occupied physically.” In a personal sense, Heisenberg might reasonably have referenced his own personal development. In a cultural sense, however, we are hard pressed to ignore the connection of Heisenberg’s statement to the multidimensional phenomenon associated with his colleague Albert Einstein. His general theory of relativity revolutionized the field of physics, his work on the photoelectric effect won him the Nobel Prize in 1921, and his mass-energy equivalence formula “E=mc2” is almost universally recognized. Yet he also exists in banal advertisements and in the fantasies of people whose daily struggles with physics center on properly tying a shoelace. Interestingly, Einstein described himself as “a man, a good European, a Jew.” For some reason, however, he felt compelled to omit two obvious aspects of his persona; that of being a scientist and that of being a musician. As he famously stated, “If I had not been a scientist, I would have been a musician. Life without playing music is inconceivable for me. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music; I get most joy in life out of music.”

Albert Einstein and Gaby Casadesus Giving Recital

© digitalchemy.wordpress.com

Like every other boy growing up in a cultured and educated German family of Jewish origins at the turn of the century, young Albert started formal musical instruction. By all accounts, his mother Pauline was a talented pianist, and Albert took up the violin. Apparently, it was not easy for him to come to terms with the rudimentary technical aspects of his instrument, and he once is supposed to have thrown a chair in frustration. However, his musical universe started to come into focus when he discovered the music of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13. In particular, he was fascinated with Mozart’s violin sonatas, a love he retained throughout the years. According to Einstein, Mozart’s music “was so pure that it seemed to have been ever-present in the universe, waiting to be discovered by the master.” As Leon Botstein rightly observed, Einstein’s partiality for Mozart was a search for “a purity of genre set against more Romantic, eclectic or contemporary musical tendencies.” In that sense, Einstein was simply part of a popular stream of modernism that was found through a purifying form of conservatism. It was Einstein’s second wife Elsa that connected her husband’s love for Mozart with his work in physics. “As a little girl, I fell in love with Albert because he played Mozart so beautifully on the violin. Music helps him when he is thinking about his theories. He goes to his study, comes back, strikes a few chords on the piano, jots something down, returns to his study.” There has been ample speculation that Einstein’s love of music somehow contributed to his scientific genius. Einstein himself did not publicly support these rather simplistic parallels, but it is nevertheless attractive to think that both Mozart and Einstein succeeded in unraveling the complexity of the universe. Einstein also worshipped Bach, and once reprimand an editor with the words, “I have this to say about Bach’s works: listen, play, love, revere — and keep your trap shut.” For obvious personal reasons, Einstein could not muster the same level of admiration for Richard Wagner. “I admire Wagner’s inventiveness, but I see his lack of architectural structure as decadence. Moreover, to me his musical personality is indescribably offensive so that for the most part I can listen to him only with disgust.

Artur Schnabel © www.jeunessesmusicales-mv.de

Once Einstein had established his renown as a physicist, he was frequently invited to perform at benefit concerts. Rather embarrassingly, a critic attending one such event, and unaware of Einstein’s real claim to fame wrote, “Herr Einstein plays excellently. However, his world-wide fame is undeserved.” Another critic sarcastically commented, “I suppose now Fritz Kreisler is going to start giving physics lectures.” Over the years, Einstein’s performing abilities have surely been exaggerated, but Leon Botstein reckons that his technical abilities ranked him as an accomplished amateur. This supposition is supported by Einstein’s friend Janos Plesch who wrote “There are many musicians with much better technique, but none, I believe, who ever played with more sincerity or deeper feeling.” It is also supported by a delightful little anecdote that exists in numerous delicious variations. In the 1920’s Einstein was invited to join a professional quartet during rehearsal. Apparently, he kept missing most of his entrances. The exasperated pianist, Artur Schnabel eventually turned to him and said: “For heaven’s sake, Albert, can’t you count?”

Sunday, December 12, 2021

Mealtime With Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

by Georg Predota, Interlude

The young Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart loved billiards, his pet starling, and food! Food was plentiful in Vienna during Mozart’s time, and a cheap and common meal would have consisted of two large meat dishes with soup, vegetables, bread, and a quarter liter of local wine.

With Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and numerous other composers hanging around, Vienna was clearly a musical center. Concurrently, it was an epicurean center that created and established the Viennese cuisine we still enjoy today. Recipes for such fabled dishes as “Wiener Schnitzel, Tafelspitz, Kaiserschmarrn, and Sacher and Linzer Torte,” became formalized and circulated in a variety of cookbooks. And Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a good and happy eater. From a journey to Milan, his father Leopold writes to his wife, “We are in God’s hands wherever we are. Wolfgang will not ruin his health by eating and drinking. He is fat and in good health, and is merry and cheerful all day long.”

Liver Dumplings

During his adult life, Mozart started his day with hot chocolate and white rolls for breakfast, and habitually had a big pot of soup for lunch. And that apparently included a local Viennese specialty called “Kuttlflecksuppe,” which roughly translates to tripe soup. Mozart also enjoyed Sturgeon, a Flemish beef and beer stew called “Carbonnade” and the large neutered rooster called “Capon.” From his letters we also learn that he frequently dined on braised pigeons with chestnuts and almond casseroles, complemented by local wines and fruits. But his all-time favorite dish was liver dumplings with sauerkraut! The dumplings are made by mixing finely ground calf liver with egg, breadcrumbs, garlic, salt and an optional splash of milk. Once they have been shaped into little balls, the dumplings are dropped in beef broth and simmered partially covered for about 15 minutes. And we all know about sauerkraut! Mozart also loved pork cutlets. In a letter from 1791 Mozart writes to his wife, “What do I smell? Why, here is Don Primus with pork cutlets! Che gusto! Now I am eating to your health!” Given the composer’s love for pork it has recently been suggested that Mozart died from trichinosis caused by the parasitic worm Trichinella predominantly found in raw pork. Whether that is actually the case or not, the disease was certainly rampant in Vienna during Mozart’s time.

Friday, December 10, 2021

The Memory Game

by Frances Wilson , Interlude

Yuja Wang (without score!)

It’s one of the great romantic images, isn’t it? The solo performer, alone on an empty stage, faced with that huge black beast of a full-size concert grand piano, armed with nothing but his or her memory and willing, well-trained fingers.

There’s a lot of snobbery surrounding memorisation, and yet it’s one of the most absurd things pianists put themselves through. We have Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt to thank (or blame!) for the tradition of the pianist playing from memory, and both were significant in turning the piano recital into the formal spectacle it is today. Before the mid-nineteenth century, pianists were not expected to play from memory and playing without the score was often considered a sign of casualness, or even arrogance: Beethoven disapproved of the practice, feeling it would make the performer lazy about the detailed markings on the score; and Chopin is reported to have been angry when he learnt that one of his pupils was intending to play him a Nocturne from memory.

Few pianists today would dispute the legacy of Liszt and Clara Schumann, and now playing from memory is almost de rigeur, so much so that if you go to a concert where the pianist plays from the score, you may hear mutterings amongst the audience, suggesting the performer isn’t up to the job or has not prepared the music properly. Which is of course rubbish: sometimes, especially in contemporary or very complex repertoire, it is simply not possible to memorise all of it. Interestingly, memorisation has actually limited the range of repertoire performed in concert: many soloists won’t commit themselves to more than a handful of works each season because of the burden memorization places upon them (as pianists, we have to learn more than double the number of notes of any other musician!).

There are sound reasons for playing from memory and it should not be regarded simply as a virtuoso affectation (the ability to memorise demonstrates a very high degree of skill and application). It can allow the performer greater physical freedom and peripheral vision, more varied expression and deeper communication with listeners. But the pressure to memorise (a pressure which is imposed upon pianists from a young age and reinforced in music college or conservatoire) can also lead to increased performance anxiety – I have come across a number of professional pianists who have given up solo work because of the unpleasant pressure to memorise and the attendant anxiety. The late great Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter gave up playing without the score when he reached his 60s as he felt he could no longer rely on his memory, and Clifford Curzon and Arthur Rubinstein both struggled with memorisation.

While each individual will have his or her own particular method of memorisation, pianists in fact utilise four types of memory, all of which must be employed when learning music:

Visual Memory: human beings use this part of their memory function to record large amounts of information, such as faces and colours and everyday objects. Music is made up of patterns and shapes, and the pianist uses visual memory to “picture” the score, as well as to recall the physical gestures involved in playing.

Aural/Auditory Memory: this is what enables us to sing in the shower! Music is an assortment of sounds, arranged in a certain order. The pianist uses aural memory to know he/she is playing the correct notes and to anticipate what he/she will play in the next few seconds.

Muscular/Procedural/Kinesthetic Memory: the ability to recall all the movements, gestures and physical sensations required to play music. Muscular or “procedural” memory is trained by repetitive practice: just as the tennis player practices his over-arm serve in exactly the same way each time to ensure a perfect delivery, so the pianist must employ repetitive practice to ensure the fingers land on the right notes every time.

Analytical/Conceptual Memory: the pianist’s ability to fully comprehend, absorb and retain the score through his/her intimate study and knowledge of it. This involves understanding structure, harmony, dynamics and nuances, phrasing, reference points, modulations, repetitions etc, as well as the context in which the music was composed, whether it is Baroque, Classical or Romantic, for example. This “total immersion” in the score should result in a rich, multi-layered awareness of it.

Many young students rely, often unconsciously, on auditory and visual memory, or on auditory and muscular memory, and many can play very competently from memory. However, to play expertly from memory, and to ensure that one’s ability to download and deliver music very accurately is completely secure, all four aspects of memory must be trained and maintained.

I go to many live piano concerts every year and I have noticed a growing trend: more solo pianists (Alexandre Tharaud is a notable example) are now using the score (accompanists and collaborative pianists tend to use the score, with the assistance of a page-turner, or the more modern alternative of an iPad or tablet with a score-reading app). It is possible to perform from the score and to deliver a quality performance which is rich in expression, gesture, and musicality. Well-managed page-turns, with the assistance of a discreet page-turner, should not detract from the performance, and after all, isn’t a concert fundamentally about communication, between performer, composer and audience? If you get that right, nothing else should matter.