It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, October 8, 2021

Thursday, October 7, 2021

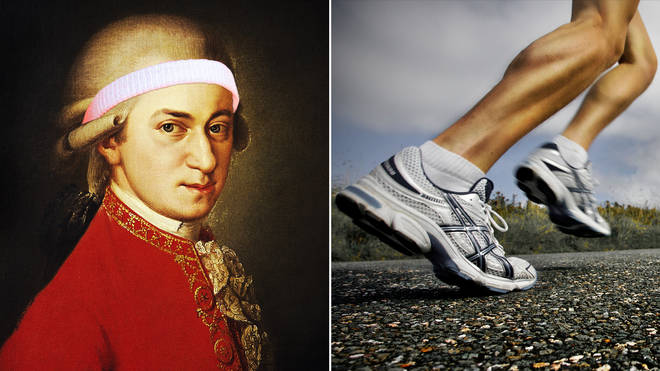

10 pieces of classical music perfect for exercise

By Sian Moore, ClassicFM London

Work up a sweat with our soundtrack of invigorating classical melodies.

Classical music can be an overlooked genre when picking a workout playlist.

But with its pacy tempos, stirring melodies and inspiring instrumentals, there’s plenty of music to get the adrenaline pumping and put you in the frame of mind for a run, swim, climb or gym session.

So, fasten your laces, start the stretching, and... da capo!

The Marriage of Figaro Overture – Mozart

The Overture to Mozart’s operatic masterpiece The Marriage of Figaro is the first musical pitstop on our list, its lively opening – an infectious, and gloriously uplifting affair led by the strings and winds – leaving its listener somewhat breathless, and lending itself perfectly to a high-energy bout of exercise.

Chariots of Fire – Vangelis

Used to score the rivalry between two athletes at the 1924 Olympics in Hugh Hudson’s film of the same name, Vangelis’ Chariots of Fire score has become synonymous with sport – namely, any slow-motion running sequences.

You might just be jogging a lap of the local park, but with Vangelis’ stirring synthesisers and percussion, you’ll be transported to an Olympics track, moments from the finishing line.

Fanfare for the Common Man – Copland

In need of some rousing encouragement before you work up a sweat? Copland has you covered with his ‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ which with its iconic brass fanfare and thundering timpani, is certain to inspire some pre-workout motivation.

For added drama, save the piece for the exact moment you reach the summit of a mountain, and indulge in the sound of victory.

1812 Overture finale – Tchaikovsky

No, it isn’t just the exercise that’s got your heart racing – the brass fanfare finale of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, a longtime favourite in the Classic FM Hall of Fame, has just begun.

If your motivation is waning, the composer’s booming cannons and crashing cymbals are sure to help. Ready for another lap of that running track now?

William Tell Overture – Rossini

We can’t imagine a more appropriate piece of music to get you over a finish line than Rossini’s Overture to his opera William Tell. The finale’s iconic, galloping climax, with its trumpet fanfare and racing lines in the string section, is the perfect piece to pop an extra spring in your step, or give you that final push.

The Four Seasons, Spring – Vivaldi

As winter emerges, the colder nights and mornings can put a dampener on anyone’s good intentions in the exercise department – but fear not, for Vivaldi is here to bring warmth, sunshine and merriness in abundance to your workout, with ‘Spring’ from his Four Seasons.

The Baroque composer’s masterpiece has all the makings of a motivational piece: sprightly strings and a timeless, inspiring melody.

Conga del Fuego – Márquez

Frantic and furious in equal measure, Mexican composer Arturo Márquez’s ‘Conga’ is a joyous affair of syncopated Latin-American rhythms and spirited strings, sure to add a little pace to your practice – of the musical or physical persuasion.

Carmen Prelude – Bizet

Bizet is waiting in line to give you a good old musical leg-up to get out of your chair and onto the track, with the infectious ‘Overture’ to his opera Carmen. But there’s no time for a warm-up with this, as Bizet throws us straight into a sea of exhilarating strings and winds, and crashing percussion.

Violin Concerto No. 9 in G Major, Op. 8 – Joseph Bologne

Run, skip, jump and swim to Joseph Boulogne’s sprightly Violin Concerto No.9 in G Major. The 18th-century composer’s piece provides a magnificent burst of energy, with its pacy strings and stimulating melody.

I Giorni – Einaudi

If yoga or pilates is your preference, or perhaps you’re searching for some musical cool-down company: look no further. Much of Einaudi’s repertoire can provide a moment of musical respite, but ‘I Giorni’ has an especially soothing quality to match slower movement, and provide room for contemplation.

After the liveliness of Copland and Mozart, here’s a much-needed breather...

(C) 2021 by ClassicFM London

Tuesday, October 5, 2021

Nine unexpected uses of Tchaikovsky’s ‘The Nutcracker’

How Tchaikovsky's ballet crops up here, there and everywhere in popular culture...

- are on Facebook

By BBC Music Magazine

Fantasia (1940)

As well as mop-wielding Mickey Mouse, Disney’s feature-length cartoon has a gorgeously animated section devoted to The Nutcracker, including music from the Sugar-Plum Fairy, the Arabian Dance, the Russian Trepak and the Waltz of the Flowers.

Barbie in the Nutcracker (2001)

Further cinematic Nutcracker delights, as a computer-animated Barbie embarks on a ballet adventure. It is, needless to say, all very pink, though our heroine does dance a neat little Sugar-Plum Fairy routine.

The Simpsons Christmas Stories (2005)

‘I hope I never hear that God-awful Nutcracker music again,’ complains a typically grumpy Homer Simpson. And guess what comes next? Yup, the Simpsons cast sings a Christmas medley to the tune of the Act I March.

Duke Ellington’s The Nutcracker Suite (1960)

Few musicians have fused the worlds of classical and jazz as sublimely as The Duke, whose 1960 take on Tchaikovsky comes complete with natty titles such as ‘Sugar Rum Cherry’ and ‘Toot Toot Tootie Toot’.

- 25 greatest jazz saxophonists of all time

- 28 best ever jazz pianists

- The best recordings of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

Nut Rocker (1962)

Two years after Duke Ellington, American rockers B. Bumble & the Stingers were inspired to create their own high-octane arrangement of The Nutcracker’s March, a version that’s been covered by Emerson, Lake and Palmer, among others.

Nutcracker (1982)

Joan Collins is in quintessentially sassy form in this splendidly awful British film about a Russian ballerina defecting to the west. Finola Hughes is the dancer in question.

Cadbury’s Fruit & Nut Advert (1976 etc)

From Frank Muir pootling around in a punt in 1976 to a 1980s office worker being serenaded by a singing chocolate bar and her hunky-chunky almonds, Cadbury’s brilliant ad campaign had us all singing ‘Everyone’s a Fruit and Nut case’ to the Dance of the Reed Pipes.

Tetris (1989)

Block-dropping fun galore, as the Nintendo Gameboy version of this ultra-popular game was accompanied by The Nutcracker’s ‘Trepak’.

Forgotten Pianists: Jorge Bolet

By Anson Yeung, Interlude

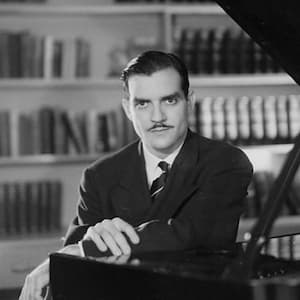

Jorge Bolet © Radio King

To say that Jorge Bolet (1914 – 1990) is “forgotten” may not be entirely correct, but he is certainly one of the most underrated pianists of the 20th century. Born in Havana, Bolet gave his first public performance at 9 and enrolled at the Curtis Institute of Music with a scholarship at 12, where he studied piano with David Saperton and conducting with Fritz Reiner. He also received mentoring from great pianists including Leopold Godowsky, Josef Hofmann and Moriz Rosenthal. These all seemed to set him for a thriving career.

Jorge Bolet rehearses in the Tanglewood Shed with Pierre Monteux conducting the BSO © Boston Symphony Orchestra

However, Bolet’s career was far from a flourishing one and had remained static for a major part of his life. He travelled extensively, taught at Indiana University and at his alma mater and recorded for small record labels, without really achieving international fame. It wasn’t until his successful recital at Carnegie Hall in 1974 that he received the recognition he fully deserved. That was a turning point in his life and led to his contract with Decca several years later.

Bolet’s playing was suave, delicate and, most importantly, genuine. Best known for his interpretations of the Romantic repertoire and piano transcriptions, he was never virtuosic merely for its own sake. His finger dexterity was undoubtedly fascinating, but it all came so naturally under his hands. Unlike his contemporaries, he preferred Baldwin and Bechstein to Steinway. This, together with his exquisite touch, makes it possible to identify him just by the sound he created on the piano.

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser Overture (arr. F. Liszt) (1974) (Jorge Bolet, piano)

This stupendous recording of Liszt’s magnificent transcription of Wagner Tannhäuser Overture was from Bolet’s breakthrough Carnegie Hall recital in 1974, only after which he experienced real success. It was outstanding on any terms – it had absolute technical command, real excitement and aplomb.

Franz Liszt: Schumann – Liebeslied, S566/R253, “Widmung” (Jorge Bolet, piano)

This has been my all-time favourite rendition of this tremendously romantic piece. It had a beautiful singing tone throughout while drawing such a wide array of orchestral colours from the piano. A perfect blend of romanticism, refinement and passion!

This performance had poetry, poise and no affectation, as usual. Observe how sensitively each phrase was crafted and how he reached such emotional intensity without the histrionics that are commonly seen today. One can sense his humbleness in his playing – there’s only music and nothing else. sly known for their extreme technical difficulty. Only a few pianists dared to perform these Études live, and Jorge Bolet was one of them. He was able to transcend the technical challenges and bring out the music despite the complexity. Everything was under complete control – the melodic line was always apparent, and the sound was so rich and lush. Sheer beauty!

Bolet was surely one of the finest musicians of his generation, having been hailed as the greatest pianist in America by Emil Gilels (another legendary pianist). Although his ascent to the rank of “great masters” had been strenuous, he has become an important part of the history of piano music and will continue to inspire pianists of future generations.

My passion of music (I)

Music is an important part of our life as it is a way of expressing our feelings as well as emotions. No matter where you are living on this globe. Some people consider music as a way to escape from the pain of life. It gives you relief and allows you to reduce stress. ... Music plays a more important role in our life than just being a source of entertainment.

“[Music] can propel narrative swiftly forward, or slow it down. It often lifts mere dialogue into the realm of poetry. It is the communicating link between the screen and the audience, reaching out and enveloping all into one single experience.” The best stories engage all of the senses.

Such is the case of Philippine music which today is regarded as a unique blending of two great musical traditions – the East and the West. ... The majority of Philippine Music revolves around cultural influences from the West, due primarily to the Spanish and American rule for over three centuries.

Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous "Sa Ugoy ng Duyan" that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for "Pandanggo sa Ilaw".

Monday, October 4, 2021

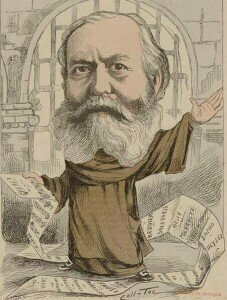

Charles Gounod - his music and his life

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand.

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand. The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera.

The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera. Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Additional projects soon followed but Gounod had no great theatrical success until he hit the jackpot with Faust derived from Goethe. Première on 19 March 1859, the opera was once more praised by Berlioz, but casting problems and a hostile press raised doubt whether Faust would be able to survive. Thanks to the efforts of the publisher Antoine de Choudens, who bought the rights and aggressively promoted the work, Faust exploded onto the European opera stages. Richard Wagner called it a “feeble French travesty of a German monument,” but he could not prevent Gounod’s Faust to become the most frequently staged operas of all time.

Gounod died on 18 October 1893, and although Ravel considered him the “real founder of the mélodie in France,” his music fell rapidly out of fashion. Gounod steadfastly believed in a universal dramatic and spiritual truth, and his refusal to pursue the implications of Wagner’s musical style placed him at odds with writers and critics alike. Debussy quipped, “Gounod, for all his weaknesses, was necessary as his art represents a moment in French sensibility.”

%20(1).jpg)