It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

Wonderland Skies - Connie Talbot (Music Video)

Monday, December 9, 2024

Ladies of Soul 2017 | Don't Let The Sun Go Down

Friday, December 6, 2024

The Blame Game – Musicians’ Excuses When Things Go Wrong

by Janet Horvath

Those of us who are musicians have tried these excuses with varying success; teachers have heard them all. Just like in other professions, musicians can be guilty of procrastinating.

After several months, once we do our dedicated practising and have put in the long, sometimes frustrating hours, our recital, concert, audition, and competition are upon us. What could possibly go wrong? Despite our best efforts, something does. These may be out of our control, like a distracting noise in the hall, terrible chairs, poor lighting, an out-of-tune piano to play with; and some not, like going to the wrong hall, arriving at the wrong time, or forgetting your music, your shoulder rest, your mouthpiece, your shoes, your glasses, or your pants. While we’re playing, no matter the hours of practice, we might have a memory slip, miss a passage, or lose our place in the music. When things happen, musicians once again come up with ingenious excuses, otherwise called the Blame Game.

How many times have we been challenged, if not foiled, by our surroundings? I’ll never forget the recital I played in a historical hall in Rome, most often used for theatrical productions. I had to make my way through a thick, dark blue velvet curtain behind which, was a minefield of stage sets, piles of wood, props, tinsel, and dust. Once I was able to negotiate getting onto the stage, snagging my dress in an exposed nail, I might add, I was alarmed to find that the rake or slope of the stage was at an incline that made me woozy. It may have helped to improve with the illusion of perspective and increase the sight lines for spectators, but once I staggered to my seat, the chair and me on the seat kept sliding forward, especially whenever I played forte. You can imagine the result in a piece like Brahms Sonata for Cello and Piano in F major Op. 99, which begins very loudly and with passion.

Performance anxiety can often get the better of us. Some musicians are not plagued by nerves, while it undoes others (and we are so jealous of them.) That subject is quite another story.

The following excuses are ever-present in the musician’s world. (For novices, there are some notes at the end of the article.)

I shouldn’t have had that double cappuccino.

I was too hungry to concentrate.

I had the flu. That’s why my bow was shaking.

The chair was too low/high.

The stand was too low/high.

The lighting was too dim/blinding.

We are quick to blame the instrument itself:

My instrument is too small/too big.

My chin rest is too low/too high.

I forgot my shoulder rest. I had to use my shoe! (violinists).

It was the reed again. It cracked and quacked (1) (oboe players).

My strings are too high off the fingerboard. I can hardly press them down (cellists).

My strings are old/cheap/false/unraveling (all strings and harp).

My bridge is warped.

My mouthpiece got stuck. (2)

My instrument is a piece of crap (all).

Someone set up the instrument all wrong! (even a novice will notice that the strings should be over the bridge not under!)

And in the case of cellists – the woes of the endpin

The endpin is warped. (3)

My end pin slipped because my rock stop/puck/strap slipped!

My endpin was too low. When I started, I tightened it as hard as I could but it s-l-o-w-l-y descended while I was playing.

It was a wolf tone. It sounded like my outboard motor. (4)

We might blame the bow or bowings:

You want how many notes or beats in one bow (or one breath!)? How long do you think my bow is? Tristan und Isolde by Wagner is a case in point.

Something is wrong with my bow!

My bow is warped.

My bow needs to be re-haired.

I need darker rosin.

Carbon fiber bows are so unresponsive.

Or the music:

This edition sucks.

It was hand scribed. What do they expect?

Kalmus!

The editor put in strange and terrible fingerings/bowings.

The page turns were impossible.

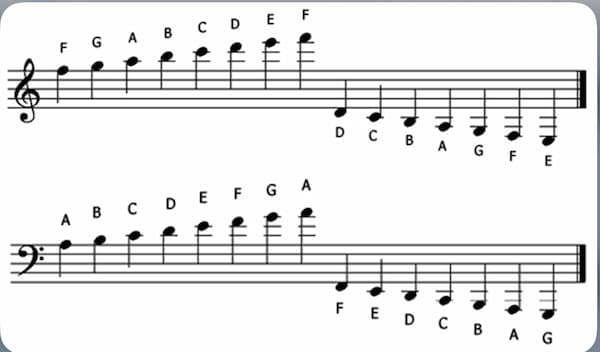

Too many leger lines! (5)

We can always resort to blaming the conductor and/or the composer:

Why did the conductor choose this piece?

What was the conductor thinking? That was an unplayable tempo.

Didn’t the conductor conduct 4 in a 3/4 bar?

The conductor got lost.

The conductor can’t conduct his/her way out of a paper bag.

The conductor glared at me.

The composer doesn’t know anything about the cello, the string family, or likely failed music theory and composition.

The composer must think we have a degree in calculus and algebra to figure out these rhythms.

When we are really piqued and need an excuse right away, we impulsively blame our stand-partner:

I missed that passage because of my stand-partner. He/she:

Didn’t get the page over fast enough.

Put the stand too far away, too high/low.

Put his/her fingerings in the part, and I couldn’t see mine.

Was singing along, and he/she has a terrible voice.

Was playing out of tune, out of rhythm, got lost, swayed too much, screwed up the bowings.

Or we can always blame the weather or travel

I got caught in the rain.

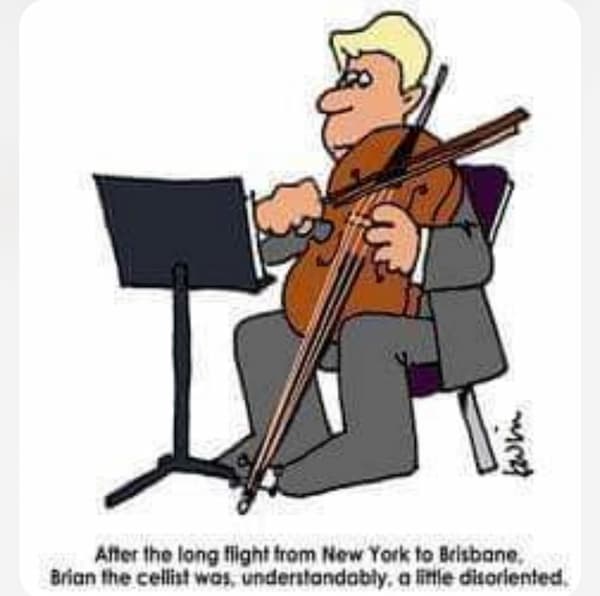

It was the jetlag.

And if these don’t work. Here are a few on an ascending scale of desperation

I usually play better.

I practised so much I almost died!

I sounded great at home.

I blame my parents.

I blame my therapist!

A swarm of termites has moved in!!

(And when all else fails)

It was the viola section’s fault. (With apologies to my amazing viola playing colleagues such as Julian Rachlin on viola in Resurrection of the Viola Player.) (6)

These are some insights into life as a musician. Jokes aside, those of us in the business know playing a musical instrument takes practice, tremendous discipline, focus, and dedication. The preparation for each concert can take months if not years, and attaining excellence is a lifetime quest. Deep down, we truly acknowledge that there are no excuses. Musicians never want to let down our audiences, our teachers, or ourselves, so we continue to pursue excellence and strive for that impeccable performance. But even more important, we endeavor to play with enough panache to move our audiences and fool them into thinking it was effortless!

Notes:

(1) A reed is used by the clarinet, oboe, English horn, and bassoon players. Many musicians carve their own reeds out of cane. Reed making is a fine art and can take years to learn as the reed is directly responsible for the response, sound quality, ease of playing, and playing in tune. Yet sometimes they might only last a few minutes as they can easily chip or crack but well-cared for, they can last 2-3 weeks depending also on how much the musician is playing. But they can sound like a QUACK!

(2) The mouthpiece of brass instruments can become stuck in the receiver. This can be caused by playing with too much pressure, when the player forgets to clean the moisture from the mouthpiece, or when the player forgets to take out the mouthpiece after playing. If it becomes stuck, it is essential to use the specially designed tool to remove it— a mouthpiece puller, that will separate the mouthpiece from the receiver without damage to the mouthpiece or pipe. Brass players call wrong notes CLAMS!

(3) Cellists may jam the sharp end of the endpin into a wooden floor, making a hole, which doesn’t please stage-managers. There are several implements available to “hold” or anchor the spike/endpin in place. These range from pucks to straps. But sometimes these slip too! Carrying the cello should be enough, but chairs are often too low. Hence bringing a wedge seat cushion.

(4) The wolf is an undesirable phenomenon that occurs on some bowed string instruments, especially on the cello. When the pitch, often an F# on the G string, is played and it is closely related to a natural, resonant frequency of the instrument, the instrument will vibrate intensely. It can be difficult to control and can sound strange, like a stuttering or warbling. Some cellists resort to a wolf tone eliminator—a small metal tube with a screw mounted on one of the strings below the bridge. They don’t work reliably. I used to squeeze my cello with my knees to reduce the vibration of the instrument and this sometimes worked. But it can still sound like a howling WOLF!

(5) Leger line is used in western musical notation. They are short lines that extend above or below the staff, placed parallel to the lines of the staff, and equidistantly spaced to denote higher or lower notes beyond the staff. Try reading these with progressive glasses or when you haven’t had enough sleep!

(6) Tristan Schulze wrote “Resurrection of the Viola Player” to be played by Julian Rachlin on the viola. This is the very first piece that Julian ever played on the viola, and he had to learn it for memory because he did not know the viola cliff well enough at the time! With violinist and comedian Aleksey Igudesman, Daisy Jopling, violin, Tristan Schulze, cello.

The Magic of Mozart: The Viennese Piano Concertos

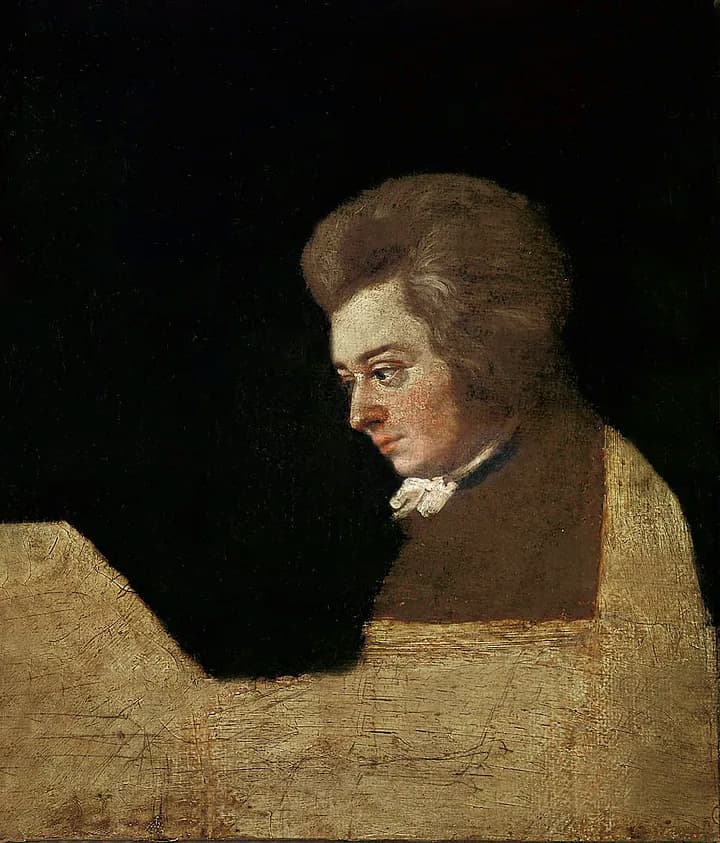

Joseph Lange: Mozart at the keyboard (unfinished), 1789 (Mozart-Museum, Mozarts Geburtshaus)

Mozart essentially created a unique conception of the piano concerto as he was looking to solve the problem of how the thematic material is to be divided between the piano and the orchestra. In these later works, Mozart “strives to maintain an ideal balance between a symphony with occasional piano solos and a virtuoso piano fantasia with orchestral accompaniment.” Mozart’s solutions are non-formulaic as each concerto, although unmistakably resembling its siblings, is a thoroughly individual response.

The Viennese piano concertos are probably the most personal works Mozart ever conceived, as they were composed for his own public performances. As we commemorate Mozart’s death on 5 December, let us explore some of these most important works of their kind.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart sent his father the list of subscribers who paid an entrance fee of six gulden for three concerts at the Trattnerhof on 20 March 1784. “Here you have the list of all my subscribers,” he writes, “I have 30 subscribers more than Richter and Fischer combined. The first concert on March 17th went off very well. The hall was full to overflowing, and the new concerto I played won extraordinary applause. Everywhere I go, I hear praises of that concerto.”

The concerto in question was Mozart’s K. 449, and Mozart had gotten involved in subscription concerts via his colleague Franz Xaver Richter. Richter had rented a hall for six Saturday concerts, and the nobility subscribed. However, as Mozart writes, “they really did not want to attend unless I played. So Richter asked me to play. I promised him to play three times and then arranged three subscription concerts for myself, to which they all subscribed.”

Mozart suggested that K. 449 “is one of a quite peculiar kind,” and he called it a happy medium between what is too easy and too difficult. In fact, K. 499 is rather intimate chamber music with the “Allegro Vivace” exploring the tensions between the major and minor tonalities. An exquisitely expressive “Andantino” gives way to a dazzling rondo featuring much contrapuntal wizardry.

The Piano Concerto No. 17, K. 453 is one of only two by Mozart to have been written for a player other than himself. In fact, it was written for his student Barbara Ployer, daughter of Gottfried Ignaz von Ployer, a Viennese emissary to the Salzburg court. Ployer was a fine pianist and she soon became one of Mozart’s favourite students. He also provided her with counterpoint instructions, and he asked her to come up with musical ideas of her own. Leopold Mozart was not impressed and wrote, “You want her to have ideas of her own—do you think everyone has your genius?”

Mozart monument in Vienna

The orchestration of this concerto is notable for the independence Mozart provided to the woodwinds. Clearly, Mozart could rely on a much higher standard of the orchestral winds than he had experienced in Salzburg. The prominence of the winds is dramatically demonstrated in the second movement, which opens with a serene theme in the strings that comes to a dramatic and operatic stop. This is followed by an extended episode in which the strings play backup for the solo flute, oboe, and bassoon.

The opening movement unfolds in a relaxed and almost casually expressive mood. One gorgeous melody seems to chase the next, and the contrasting theme ventures into unexpected tonal areas. Instead of the expected rondo, the finale presents five variations on a simple tune but then pauses and seemingly jumps into an entirely new movement. Barbara Ployer played the premiere in June 1784.

Mozart benefited artistically and financially from his subscription concerts. And he certainly enjoyed his time as the darling of the Viennese concert scene. The Piano Concerto No. 19 premiered in the spring of 1785, possibly one of the busiest periods of Mozart’s life as a performer. Leopold came for a ten-week visit and was struck by the level of activity. “Every day, there are concerts, and the whole time is given up to teaching, music, composing and so forth. Since my arrival, your brother’s fortepiano has been taken at least a dozen times to the theatre or some other house.”

As Alfred Brendel writes, “the first movement of K. 459 is remarkable; no other movement in the whole series of twenty-three piano concertos evinces such subordination on the part of the piano to the orchestra: purely solo passages are rare, and for much of time the solo instrument is occupied in providing an accompaniment to various sections of the orchestra, notably the woodwinds.” That opening movement, unusually, also relies entirely on one theme, a march-like melody that dominates proceedings.

The slow movement forgoes a development section and sounds like a close collaboration among the soloist, the strings and the winds. That dialogue between the instrumental forces culminates in a final coda. The sonata-rondo finale seems a fitting conclusion as it playfully takes us into the world of opera buffa.

Mozart entered the Piano Concerto in D Minor, K. 466, in his new catalogue of compositions on 10th February 1785. It is the first of his piano concertos in the minor key. To be sure, the minor tonality adds a new dimension of high seriousness to the form, a mood immediately heard in the dramatic orchestral opening. The concerto is scored for trumpets and drums, as well as the now usual flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons and horns, with strings, and the violas divided.

Leopold Mozart was present at the premiere, and he wrote to his daughter, “We drove to Wolfgang’s first subscription concerto, at which a great many members of the aristocracy were present… Then we had a new and very fine concerto by Wolfgang, which the copyist was still copying when we arrived, and the rondo of which your brother did not even have time to play through as he had to supervise the copying.” Isn’t it amazing that in about three weeks, Mozart was able to write the most perfect and most passionate of concertos?

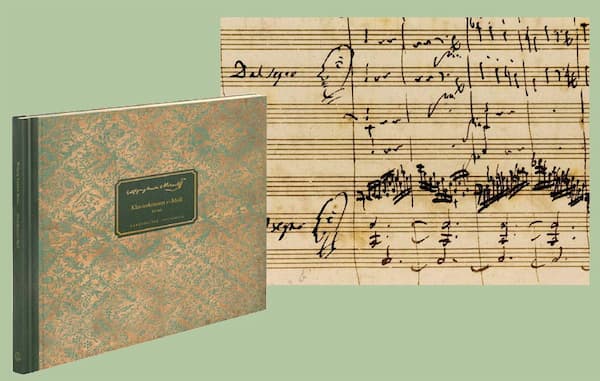

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 autograph score

The D-minor concerto was a turning point as it was Mozart’s first “symphonic” concerto. The orchestra is given a completely equal position, and the wind parts become even more weighty. The sense of drama is evident in the large-scale orchestral introduction, and many of the piano parts would comfortably fit into an operatic seria. However, they are much more than just a beautiful melody. A noted performer writes, “Mozart probably found in D minor the threatening and demonic colouring he was looking for. A very personal statement!”

Mozart completed his 21st Piano Concerto in C Major, K. 467, on 9 March 1785, exactly a month after the premiere of his first concerto in the minor key. Contrary to the dramatic narrative of K. 466, the C-Major Concerto is a work filled with humour that focuses on elegant simplicity. A critic reported that Mozart’s playing “captivated every listener and established Mozart as the greatest keyboard player of his day.” Leopold Mozart added that the work was “astonishingly difficult,” and it would be the last time that father and son would actually see each other.

Presently, this concerto is known as the Elvira Madigan Concerto because the use of the second movement contributed strongly to the mood of the film of that name. The work opens quietly, with unison strings setting an opera buffa stage. There is an air of anticipation as the winds once again play an important role. They initiate little fanfare, double the strings, or even capture centre stage with melodic interjections. The soloist enters with new and independent ideas and then follows its own path.

Soloist and orchestra have a unique relationship here as both forces seem primarily concerned with their own material. As Donald Francis Tovey writes, “In no other concerto does Mozart carry so far the separation between the two… Mozart has succeeded in making the piano as capable a vehicle of his thought as the orchestra.” The dream-like and elegant second movement provides for a nocturnal atmosphere, while the concluding “Rondo” returns us to the opening mood. Mozart borrowed a theme from his concerto for Two Pianos, K. 365, and the entire movement is based on that witty tune with plenty of scope for soloists and the orchestra to show their brilliance.

Mozart completed his Piano Concerto in A Major, K. 488, on 2 March 1786. It was designed for use in a series of three subscription concerts that Mozart had arranged for part of the winter season. Simultaneously, Mozart was busy working on his first Italian opera for Vienna, Le nozze di Figaro. Yet, times had changed. Only three years earlier, the Viennese public had lavishly acclaimed the piano concertos by the young virtuoso; now, they sought musical entertainment elsewhere.

The concerts were not well subscribed, but Mozart nevertheless went ahead “believing that he could seduce the public with his unquenchable ability to come up with something new and tantalising.” K. 488 has remained popular and frequently performed as it creates a sense of weightlessness. And the role of the piano becomes even more versatile. It functions as a solo instrument and accompanies the orchestra, but it also integrates into the orchestra. In a sense, it functions as an orchestral instrument.

In his orchestration, Mozart replaced the bright-toned oboes with clarinets, providing a much darker colouration. This is particularly evident in the passionate and richly chromatic slow movement in the unusual key of F-sharp minor. However, the orchestration remains essentially intimate, as Mozart foregoes trumpets and drums. The chamber-music feeling of the first two movements is reinforced by active interchanges between the woodwinds. The soloist initiates an extensive rondo finale that has the character of a fast stretta, all ending in a buffo-like coda.

The second piano concerto in the minor key, the Concerto in C-minor, K. 491, was completed on 14 March 1786. It is scored for clarinets and oboes, flutes, pairs of bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums, and strings. It opens with an ominous theme that Beethoven would subsequently use as the inspiration for his C-minor Piano Concerto. A sense of foreboding permeates the entire movement, disturbed only momentarily by the tranquillity of the second theme.

Piano Concerto C minor K. 491 by W. A. Mozart

The ”Larghetto” movement opens in the major key, and episodes are framed by the principle melody. However, the music is soon led into the minor key by the woodwind, and a ray of serenity returns us to the opening. Mozart concludes this masterwork with a set of variations.

Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat Major, K. 595

Mozart completed the cycle of twelve Viennese concertos in December 1786. He waited almost 14 months to write another piano concerto, the so-called “Coronation.” Another three years passed before he brought this grand series to a close with the B-flat Major Concerto, K. 595. To scholars, this “work stands along, not only in terms of its chronological separation from the other piano concertos but because its content and character make it unique.” It is probably the most deeply personal of all Mozart concertos.

The clearly defined drama of the minor key concertos is replaced by what has been described as “a more personal notably resigned accent” and a feeling of “subdued gravity.” Mozart gave the premiere on 4 March 1791, and it was the last such appearance before the Viennese public. Alfred Einstein wrote, “it was not in the Requiem that Mozart said his last word… but in this work, which belongs to a species in which he also said his greatest.”

Maria Callas sings "Casta Diva" (Bellini: Norma, Act 1)

Maria by Callas: “When My Enemies Stop Hissing, I Shall Know I’m Slipping”

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Maria Callas, 1958

Callas faced countless struggles on her way to success, including a seriously bad eating habit. Always deeply insecure about her weight, Callas is believed to have weighed more than 200 pounds at some stage. Within the span of two years, Callas dropped about 80 pounds, and it was rumoured that she ingested a live tapeworm in an attempt to shed the pounds. Actually, this particularly revolting diet dates back to the Victorian age and involves swallowing a pill containing a tapeworm egg. Once the egg eventually hatches, the tapeworm will grow inside the body and consume the food you are eating. There was also another rumour that Callas experimented with a special kind of pasta. However, the soprano rejected the gossip and claimed that she had lost weight naturally.

Maria, born on December 2, 1923, always saw her mother, Evangelia, as her biggest enemy. “She despised her mother for being materialistic, primitive, and self-conscious while denying the fact that she possessed most, if not all, of these qualities.” To be sure, an overbearing mother raised her, “whose ultimate dream was to make her daughter the finest opera artist in the world.” As a psychologist reports, “While chasing this dream, she neglected the physical as well as psychological needs of her unwanted daughter. The pressure and suffering she faced at the hands of both family and strangers took away her childhood from her, leaving the void of a long-lasting desire to be loved. Her life might have seemed like a dream at the peak of her career, but the heroines that Maria depicted onstage were nowhere to be seen in her private life.”

The Callas Family, 1924

It became easy for Maria to blame her mother for every difficulty and failure, and she openly rejected her mother’s advice. That was particularly true when she accepted a marriage proposal from Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who was thirty years older than her. After her marriage, the relationship between mother and daughter further deteriorated. As Maria wrote to her godfather, “I beg you not to repeat this, but my mother wrote a letter cursing as is her usual way (she thinks) of obtaining things… believe me, I did and I will do my best for them, but I will not permit them to exaggerate. I have a future to think of, and also I would like a child of my own.”

A recent biography suggests, “Callas resented her mother, who worked as a prostitute during the war, for trying to pimp her out to Nazi soldiers.” It has also been suggested that Evangelia sold stories to the press and blackmailed her daughter to keep her mouth shut. As she writes to her daughter, “You know what cinema artists of humble origins do as soon as they become rich? In the first month, they spend their first money to make a home for their parents and spoil them with luxuries… What have you got to say, Maria?”

Statue of Maria Callas in Athens

Not that the relationship with her father was any better. George wasn’t particularly interested in his daughter’s musical education but mainly interested in running his drugstore. When he had to sell his pharmacy and became a travelling salesperson for a pharmaceutical company, money was a huge problem. He resented having to pay for the piano lessons for his daughters, and he was livid about his wife’s empty dreams of living in unnecessary luxuries. In addition, George was a bit of a ladies man, and was not shy about having countless affairs, as his wife wrote, “Like a bee to whom every woman was a flower over which he must hover to seek the sweetness.” Apparently, Maria thought of him “as a caring man with limited interests who lacked empathy.” At some point, Callas wrote, “I am fed up with my parents’ egoism and indifference toward me … I want no more relationship. I hope the newspapers don’t catch on. Then I’ll really curse the moment I have any parents at all.”

Much has been written on the romantic relationships of Maria Callas, and her first love interest was Giovanni Battista Meneghini, an industrialist from Verona and an opera fan. He was smitten with Callas from the very beginning, and she enjoyed the love, warmth, and security she never got from her own family. “He made Maria the center of his attention and became a constant source of reassurance. Maria, who faced negativity, jealousy, resentment, and hostility almost her entire life, was overjoyed by the fact that Meneghini considered her a pure genius and the most talented woman in the world.”

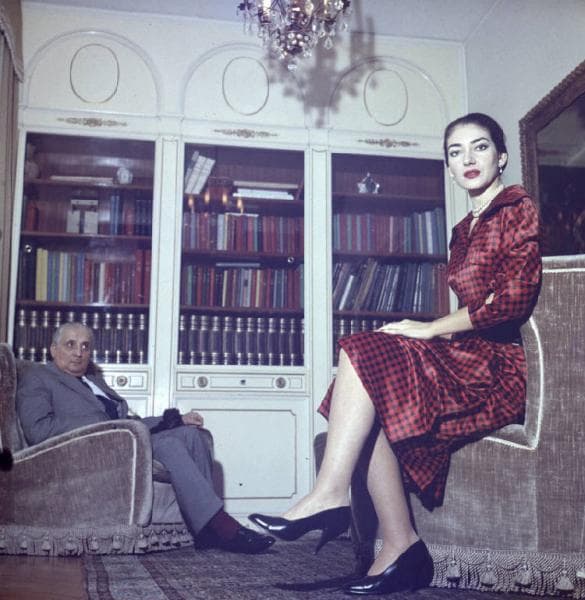

Maria Callas and Giovanni Battista Meneghini

Since he was 30 years her senior, however, both their respective families were against the marriage. Maria’s mother couldn’t see beyond the 30-year age gap, and his family thought that Maria was only interested in his money. In the event, her career took off like a rocket, which completely overwhelmed and overshadowed Meneghini’s managerial role. Scholars have suggested that Meneghini was not in love with Maria “but with what she represented.” In a later interview, Maria explained “there was nothing special about her husband, but that she continued to stay married to him in hopes that there was love between them.” Things were bound to get worse, and on the pain of her marriage to Meneghini, Callas despaired: “My husband is still pestering me after having robbed me of more than half my money by putting everything in his name since we were married … I was a fool … to trust him.” She described him as “a louse,” lamenting that he “passes for a millionaire when he hasn’t got a dime.”

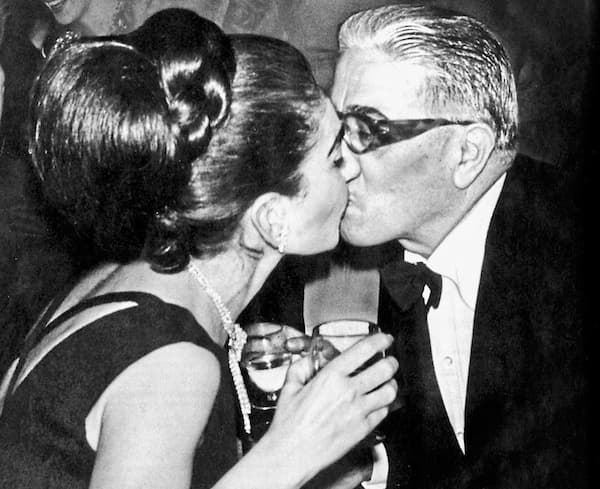

While still married to Meneghini, Callas was introduced to shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis at a party in 1957. He was devoted to her despite his lack of interest in opera. “Maria loved the fact that she was the focus of his love, attention, and energy. Onassis did everything to make her feel like the center of the universe, and the hospitality, care, and luxury she experienced made her feel like living in a fairy tale.” She decided to leave Meneghini, despite threats, accusations, and pleas. Maria claimed, “When I met Aristo, so full of life, I became a different woman.”

Maria Callas and Aristotle Onassis

The affair was front-page news, as was the fact that Callas largely abandoned her career. A commentator writes, “Onassis offered her a way out of a career that was made increasingly difficult by scandals and by vocal resources that were diminishing at an alarming rate.” Even before meeting Onassis, Maria probably realised that she needed a break. As she explained, “I want to live, just like a normal woman, with children, a home, a dog.” There has been much gossip surrounding Maria’s wish to have children. It was rumoured that she bore a son to Aristotle Onassis but that the child died soon after birth. Another rumour has it that she had at least one abortion while she was with Onassis. The relationship ended in 1968 when Onassis left Callas for Jacqueline Kennedy. However, Callas continued her affair with Onassis during his marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy. Supposedly, he frequently met Maria in Paris where they resumed what had now become a clandestine affair. And we do know that Aristotle’s children hated Maria for being “the other woman” in their father’s life. As Maria later wrote, “There are not many men who can be near me. It’s a sort of handicap to be famous. Also I have a very active mind, a strong personality, and I might frighten real men away.”

The relationship with Onassis, however, appears to have had some seriously sinister undertones. In fact, he seemed to have been a remarkably crude, trivial and nasty man. A recent biography based on previously unpublished correspondence claims that Onassis abused Callas, especially in 1966, “when his physical violence threatened her life.” There also seems to be some indication in the diary of a close friend that “Onassis drugged her, mostly for sexual reasons.” As Callas confided to her secretary, “I wouldn’t want Onassis to phone me and start again torturing me.” Date raped by Onassis, the director of one of the world’s foremost conservatoires, Peter Mennin, apparently also sexually harassed Callas. He was the then president of the Juilliard School in New York, a married man who turned the faculty against her and “stopped her coming back for another term after she rejected his advances.” As she wrote to her godfather, “Peter Mennin fell in love with me. So, naturally, as I did not feel so towards him, he is against me.” Mennin’s family, in turn, claims that he sought to distance himself from Callas, who had become infatuated with him.

From her earliest beginnings, Maria Callas was subjected to severe criticism from her colleagues. When she was made a permanent member of the Athens Opera, it attracted intense envy and jealousy from the members of the Opera. Some of them thought that Maria’s upper register had “too much metal” in it, others complained about her disruptive top and her unconventional way of singing. “Her seniors at Athens Opera were convinced that Maria’s flaws were not curable, as teaching can only refine natural talent, which Maria was clearly lacking.”

Maria Callas and Giovanni Battista Meneghini, 1957

While Callas might have been insecure in most parts of her life, she was indeed very confident and outspoken when it came to music. She harshly criticised the leading coloratura soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, Lily Pons, for singing off-key in a performance as Lucia di Lammermoor. Callas bluntly told the press that “she did not care about how important Lily was, and the only thing that mattered to her was the vocal technique she had used.” Intense rivalry supposedly also arose between Callas and Renata Tebaldi, an Italian lyric soprano. “The contrast between Callas’s often unconventional vocal qualities and Tebaldi’s classically beautiful sound resurrected an argument as old as opera itself, namely, beauty of sound versus the expressive use of sound.”

It all kicked off in 1951, when Tebaldi and Callas were jointly booked for a vocal recital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The singers agreed that neither would perform encores, but Tebaldi took two, and Callas was not amused. “This incident began the rivalry, which reached a fever pitch in the mid-1950s, at times even engulfing the two women themselves, who were said by their more fanatical followers to have engaged in verbal barbs in each other’s direction.” Tebaldi was quoted as saying, “I have one thing that Callas doesn’t have: a heart.” In return, Callas was quoted in Time magazine as saying that comparing her with Tebaldi was like “comparing Champagne with Cognac…No…with Coca Cola.”

Renata Tebaldi

In a recently unearthed letter, Callas reveals her full loathing for Tebaldi. Basically, she accused her of finding fame through “being my rival,” and for using her mother’s reported heart attack to further her career. Callas writes, “Her mother had nothing special wrong with her. Not even a heart attack… Do you think it’s publicity or maybe Renata did not feel well and [maybe] her mother had the flu and that was a perfect excuse for her not singing… and to have a triumphant poor Renata on her first performance.” Summing up, Callas writes, “I’m surely fed up with all this nauseating poor Renata business… God does not like such methods for publicity and weapons against me.” Seemingly, however, they had great respect for their vocal abilities and officially denied that they had any kind of animosity. Denial of their feud aside, Callas wrote of Tebaldi: “She’s as nasty and as sly as they come.”

In 1978, Tebaldi said, “This rivalry was really building from the people of the newspapers and the fans. But I think it was very good for both of us, because the publicity was so big and it created a very big interest about me and Maria and was very good in the end. But I don’t know why they put this kind of rivalry because the voice was very different. She was really something unusual. And I remember that I was a very young artist too, and I stayed near the radio every time that I knew that there was something on the radio by Maria.” Callas was a perfectionist who set almost unattainable goals. For a good many colleagues, Callas was a very difficult artist to work with, “because she was so much more intelligent. Other artists, you could get around. But not Callas, as she knew exactly what she wanted and why she wanted it.” Despite being perceived as a temperamental prima donna, Callas saw herself as a caring person. “I want to give a little happiness even if I haven’t had much for myself. Music has enriched my life and, hopefully – through me, a little – the public’s. If anyone left an opera house feeling more happy and at peace, I have achieved my purpose.”