by Georg Predota, Interlude

Maria Callas, 1958

Callas faced countless struggles on her way to success, including a seriously bad eating habit. Always deeply insecure about her weight, Callas is believed to have weighed more than 200 pounds at some stage. Within the span of two years, Callas dropped about 80 pounds, and it was rumoured that she ingested a live tapeworm in an attempt to shed the pounds. Actually, this particularly revolting diet dates back to the Victorian age and involves swallowing a pill containing a tapeworm egg. Once the egg eventually hatches, the tapeworm will grow inside the body and consume the food you are eating. There was also another rumour that Callas experimented with a special kind of pasta. However, the soprano rejected the gossip and claimed that she had lost weight naturally.

Maria, born on December 2, 1923, always saw her mother, Evangelia, as her biggest enemy. “She despised her mother for being materialistic, primitive, and self-conscious while denying the fact that she possessed most, if not all, of these qualities.” To be sure, an overbearing mother raised her, “whose ultimate dream was to make her daughter the finest opera artist in the world.” As a psychologist reports, “While chasing this dream, she neglected the physical as well as psychological needs of her unwanted daughter. The pressure and suffering she faced at the hands of both family and strangers took away her childhood from her, leaving the void of a long-lasting desire to be loved. Her life might have seemed like a dream at the peak of her career, but the heroines that Maria depicted onstage were nowhere to be seen in her private life.”

The Callas Family, 1924

It became easy for Maria to blame her mother for every difficulty and failure, and she openly rejected her mother’s advice. That was particularly true when she accepted a marriage proposal from Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who was thirty years older than her. After her marriage, the relationship between mother and daughter further deteriorated. As Maria wrote to her godfather, “I beg you not to repeat this, but my mother wrote a letter cursing as is her usual way (she thinks) of obtaining things… believe me, I did and I will do my best for them, but I will not permit them to exaggerate. I have a future to think of, and also I would like a child of my own.”

A recent biography suggests, “Callas resented her mother, who worked as a prostitute during the war, for trying to pimp her out to Nazi soldiers.” It has also been suggested that Evangelia sold stories to the press and blackmailed her daughter to keep her mouth shut. As she writes to her daughter, “You know what cinema artists of humble origins do as soon as they become rich? In the first month, they spend their first money to make a home for their parents and spoil them with luxuries… What have you got to say, Maria?”

Statue of Maria Callas in Athens

Not that the relationship with her father was any better. George wasn’t particularly interested in his daughter’s musical education but mainly interested in running his drugstore. When he had to sell his pharmacy and became a travelling salesperson for a pharmaceutical company, money was a huge problem. He resented having to pay for the piano lessons for his daughters, and he was livid about his wife’s empty dreams of living in unnecessary luxuries. In addition, George was a bit of a ladies man, and was not shy about having countless affairs, as his wife wrote, “Like a bee to whom every woman was a flower over which he must hover to seek the sweetness.” Apparently, Maria thought of him “as a caring man with limited interests who lacked empathy.” At some point, Callas wrote, “I am fed up with my parents’ egoism and indifference toward me … I want no more relationship. I hope the newspapers don’t catch on. Then I’ll really curse the moment I have any parents at all.”

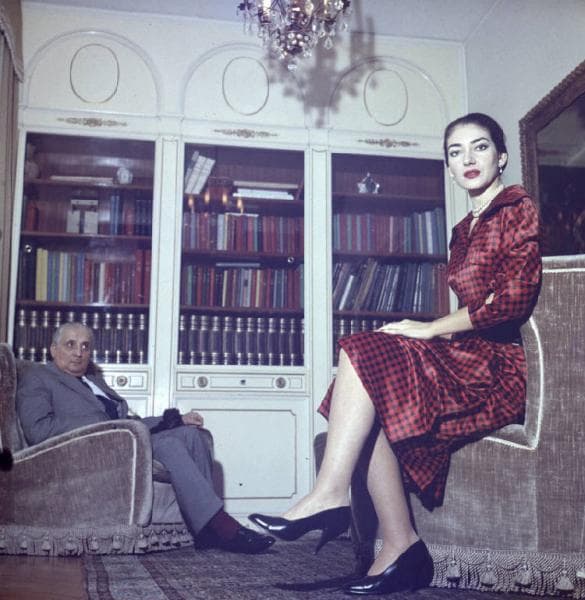

Much has been written on the romantic relationships of Maria Callas, and her first love interest was Giovanni Battista Meneghini, an industrialist from Verona and an opera fan. He was smitten with Callas from the very beginning, and she enjoyed the love, warmth, and security she never got from her own family. “He made Maria the center of his attention and became a constant source of reassurance. Maria, who faced negativity, jealousy, resentment, and hostility almost her entire life, was overjoyed by the fact that Meneghini considered her a pure genius and the most talented woman in the world.”

Maria Callas and Giovanni Battista Meneghini

Since he was 30 years her senior, however, both their respective families were against the marriage. Maria’s mother couldn’t see beyond the 30-year age gap, and his family thought that Maria was only interested in his money. In the event, her career took off like a rocket, which completely overwhelmed and overshadowed Meneghini’s managerial role. Scholars have suggested that Meneghini was not in love with Maria “but with what she represented.” In a later interview, Maria explained “there was nothing special about her husband, but that she continued to stay married to him in hopes that there was love between them.” Things were bound to get worse, and on the pain of her marriage to Meneghini, Callas despaired: “My husband is still pestering me after having robbed me of more than half my money by putting everything in his name since we were married … I was a fool … to trust him.” She described him as “a louse,” lamenting that he “passes for a millionaire when he hasn’t got a dime.”

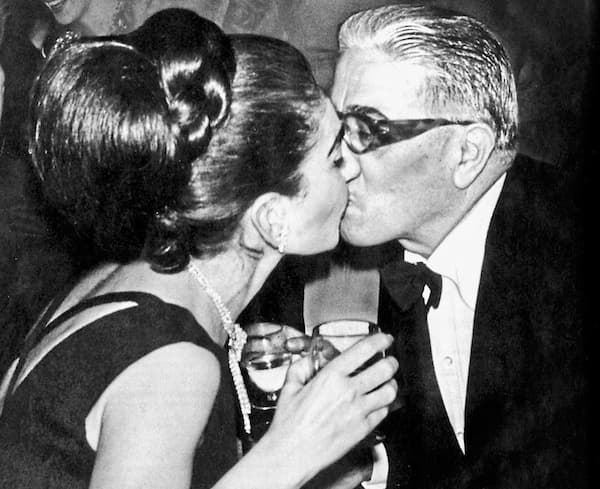

While still married to Meneghini, Callas was introduced to shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis at a party in 1957. He was devoted to her despite his lack of interest in opera. “Maria loved the fact that she was the focus of his love, attention, and energy. Onassis did everything to make her feel like the center of the universe, and the hospitality, care, and luxury she experienced made her feel like living in a fairy tale.” She decided to leave Meneghini, despite threats, accusations, and pleas. Maria claimed, “When I met Aristo, so full of life, I became a different woman.”

Maria Callas and Aristotle Onassis

The affair was front-page news, as was the fact that Callas largely abandoned her career. A commentator writes, “Onassis offered her a way out of a career that was made increasingly difficult by scandals and by vocal resources that were diminishing at an alarming rate.” Even before meeting Onassis, Maria probably realised that she needed a break. As she explained, “I want to live, just like a normal woman, with children, a home, a dog.” There has been much gossip surrounding Maria’s wish to have children. It was rumoured that she bore a son to Aristotle Onassis but that the child died soon after birth. Another rumour has it that she had at least one abortion while she was with Onassis. The relationship ended in 1968 when Onassis left Callas for Jacqueline Kennedy. However, Callas continued her affair with Onassis during his marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy. Supposedly, he frequently met Maria in Paris where they resumed what had now become a clandestine affair. And we do know that Aristotle’s children hated Maria for being “the other woman” in their father’s life. As Maria later wrote, “There are not many men who can be near me. It’s a sort of handicap to be famous. Also I have a very active mind, a strong personality, and I might frighten real men away.”

The relationship with Onassis, however, appears to have had some seriously sinister undertones. In fact, he seemed to have been a remarkably crude, trivial and nasty man. A recent biography based on previously unpublished correspondence claims that Onassis abused Callas, especially in 1966, “when his physical violence threatened her life.” There also seems to be some indication in the diary of a close friend that “Onassis drugged her, mostly for sexual reasons.” As Callas confided to her secretary, “I wouldn’t want Onassis to phone me and start again torturing me.” Date raped by Onassis, the director of one of the world’s foremost conservatoires, Peter Mennin, apparently also sexually harassed Callas. He was the then president of the Juilliard School in New York, a married man who turned the faculty against her and “stopped her coming back for another term after she rejected his advances.” As she wrote to her godfather, “Peter Mennin fell in love with me. So, naturally, as I did not feel so towards him, he is against me.” Mennin’s family, in turn, claims that he sought to distance himself from Callas, who had become infatuated with him.

From her earliest beginnings, Maria Callas was subjected to severe criticism from her colleagues. When she was made a permanent member of the Athens Opera, it attracted intense envy and jealousy from the members of the Opera. Some of them thought that Maria’s upper register had “too much metal” in it, others complained about her disruptive top and her unconventional way of singing. “Her seniors at Athens Opera were convinced that Maria’s flaws were not curable, as teaching can only refine natural talent, which Maria was clearly lacking.”

Maria Callas and Giovanni Battista Meneghini, 1957

While Callas might have been insecure in most parts of her life, she was indeed very confident and outspoken when it came to music. She harshly criticised the leading coloratura soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, Lily Pons, for singing off-key in a performance as Lucia di Lammermoor. Callas bluntly told the press that “she did not care about how important Lily was, and the only thing that mattered to her was the vocal technique she had used.” Intense rivalry supposedly also arose between Callas and Renata Tebaldi, an Italian lyric soprano. “The contrast between Callas’s often unconventional vocal qualities and Tebaldi’s classically beautiful sound resurrected an argument as old as opera itself, namely, beauty of sound versus the expressive use of sound.”

It all kicked off in 1951, when Tebaldi and Callas were jointly booked for a vocal recital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The singers agreed that neither would perform encores, but Tebaldi took two, and Callas was not amused. “This incident began the rivalry, which reached a fever pitch in the mid-1950s, at times even engulfing the two women themselves, who were said by their more fanatical followers to have engaged in verbal barbs in each other’s direction.” Tebaldi was quoted as saying, “I have one thing that Callas doesn’t have: a heart.” In return, Callas was quoted in Time magazine as saying that comparing her with Tebaldi was like “comparing Champagne with Cognac…No…with Coca Cola.”

Renata Tebaldi

In a recently unearthed letter, Callas reveals her full loathing for Tebaldi. Basically, she accused her of finding fame through “being my rival,” and for using her mother’s reported heart attack to further her career. Callas writes, “Her mother had nothing special wrong with her. Not even a heart attack… Do you think it’s publicity or maybe Renata did not feel well and [maybe] her mother had the flu and that was a perfect excuse for her not singing… and to have a triumphant poor Renata on her first performance.” Summing up, Callas writes, “I’m surely fed up with all this nauseating poor Renata business… God does not like such methods for publicity and weapons against me.” Seemingly, however, they had great respect for their vocal abilities and officially denied that they had any kind of animosity. Denial of their feud aside, Callas wrote of Tebaldi: “She’s as nasty and as sly as they come.”

In 1978, Tebaldi said, “This rivalry was really building from the people of the newspapers and the fans. But I think it was very good for both of us, because the publicity was so big and it created a very big interest about me and Maria and was very good in the end. But I don’t know why they put this kind of rivalry because the voice was very different. She was really something unusual. And I remember that I was a very young artist too, and I stayed near the radio every time that I knew that there was something on the radio by Maria.” Callas was a perfectionist who set almost unattainable goals. For a good many colleagues, Callas was a very difficult artist to work with, “because she was so much more intelligent. Other artists, you could get around. But not Callas, as she knew exactly what she wanted and why she wanted it.” Despite being perceived as a temperamental prima donna, Callas saw herself as a caring person. “I want to give a little happiness even if I haven’t had much for myself. Music has enriched my life and, hopefully – through me, a little – the public’s. If anyone left an opera house feeling more happy and at peace, I have achieved my purpose.”