by Janet Horvath

Those of us who are musicians have tried these excuses with varying success; teachers have heard them all. Just like in other professions, musicians can be guilty of procrastinating.

After several months, once we do our dedicated practising and have put in the long, sometimes frustrating hours, our recital, concert, audition, and competition are upon us. What could possibly go wrong? Despite our best efforts, something does. These may be out of our control, like a distracting noise in the hall, terrible chairs, poor lighting, an out-of-tune piano to play with; and some not, like going to the wrong hall, arriving at the wrong time, or forgetting your music, your shoulder rest, your mouthpiece, your shoes, your glasses, or your pants. While we’re playing, no matter the hours of practice, we might have a memory slip, miss a passage, or lose our place in the music. When things happen, musicians once again come up with ingenious excuses, otherwise called the Blame Game.

How many times have we been challenged, if not foiled, by our surroundings? I’ll never forget the recital I played in a historical hall in Rome, most often used for theatrical productions. I had to make my way through a thick, dark blue velvet curtain behind which, was a minefield of stage sets, piles of wood, props, tinsel, and dust. Once I was able to negotiate getting onto the stage, snagging my dress in an exposed nail, I might add, I was alarmed to find that the rake or slope of the stage was at an incline that made me woozy. It may have helped to improve with the illusion of perspective and increase the sight lines for spectators, but once I staggered to my seat, the chair and me on the seat kept sliding forward, especially whenever I played forte. You can imagine the result in a piece like Brahms Sonata for Cello and Piano in F major Op. 99, which begins very loudly and with passion.

Performance anxiety can often get the better of us. Some musicians are not plagued by nerves, while it undoes others (and we are so jealous of them.) That subject is quite another story.

The following excuses are ever-present in the musician’s world. (For novices, there are some notes at the end of the article.)

I shouldn’t have had that double cappuccino.

I was too hungry to concentrate.

I had the flu. That’s why my bow was shaking.

The chair was too low/high.

The stand was too low/high.

The lighting was too dim/blinding.

We are quick to blame the instrument itself:

My instrument is too small/too big.

My chin rest is too low/too high.

I forgot my shoulder rest. I had to use my shoe! (violinists).

It was the reed again. It cracked and quacked (1) (oboe players).

My strings are too high off the fingerboard. I can hardly press them down (cellists).

My strings are old/cheap/false/unraveling (all strings and harp).

My bridge is warped.

My mouthpiece got stuck. (2)

My instrument is a piece of crap (all).

Someone set up the instrument all wrong! (even a novice will notice that the strings should be over the bridge not under!)

And in the case of cellists – the woes of the endpin

The endpin is warped. (3)

My end pin slipped because my rock stop/puck/strap slipped!

My endpin was too low. When I started, I tightened it as hard as I could but it s-l-o-w-l-y descended while I was playing.

It was a wolf tone. It sounded like my outboard motor. (4)

We might blame the bow or bowings:

You want how many notes or beats in one bow (or one breath!)? How long do you think my bow is? Tristan und Isolde by Wagner is a case in point.

Something is wrong with my bow!

My bow is warped.

My bow needs to be re-haired.

I need darker rosin.

Carbon fiber bows are so unresponsive.

Or the music:

This edition sucks.

It was hand scribed. What do they expect?

Kalmus!

The editor put in strange and terrible fingerings/bowings.

The page turns were impossible.

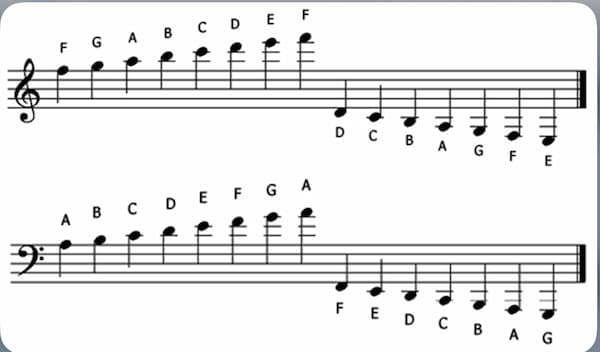

Too many leger lines! (5)

We can always resort to blaming the conductor and/or the composer:

Why did the conductor choose this piece?

What was the conductor thinking? That was an unplayable tempo.

Didn’t the conductor conduct 4 in a 3/4 bar?

The conductor got lost.

The conductor can’t conduct his/her way out of a paper bag.

The conductor glared at me.

The composer doesn’t know anything about the cello, the string family, or likely failed music theory and composition.

The composer must think we have a degree in calculus and algebra to figure out these rhythms.

When we are really piqued and need an excuse right away, we impulsively blame our stand-partner:

I missed that passage because of my stand-partner. He/she:

Didn’t get the page over fast enough.

Put the stand too far away, too high/low.

Put his/her fingerings in the part, and I couldn’t see mine.

Was singing along, and he/she has a terrible voice.

Was playing out of tune, out of rhythm, got lost, swayed too much, screwed up the bowings.

Or we can always blame the weather or travel

I got caught in the rain.

It was the jetlag.

And if these don’t work. Here are a few on an ascending scale of desperation

I usually play better.

I practised so much I almost died!

I sounded great at home.

I blame my parents.

I blame my therapist!

A swarm of termites has moved in!!

(And when all else fails)

It was the viola section’s fault. (With apologies to my amazing viola playing colleagues such as Julian Rachlin on viola in Resurrection of the Viola Player.) (6)

These are some insights into life as a musician. Jokes aside, those of us in the business know playing a musical instrument takes practice, tremendous discipline, focus, and dedication. The preparation for each concert can take months if not years, and attaining excellence is a lifetime quest. Deep down, we truly acknowledge that there are no excuses. Musicians never want to let down our audiences, our teachers, or ourselves, so we continue to pursue excellence and strive for that impeccable performance. But even more important, we endeavor to play with enough panache to move our audiences and fool them into thinking it was effortless!

Notes:

(1) A reed is used by the clarinet, oboe, English horn, and bassoon players. Many musicians carve their own reeds out of cane. Reed making is a fine art and can take years to learn as the reed is directly responsible for the response, sound quality, ease of playing, and playing in tune. Yet sometimes they might only last a few minutes as they can easily chip or crack but well-cared for, they can last 2-3 weeks depending also on how much the musician is playing. But they can sound like a QUACK!

(2) The mouthpiece of brass instruments can become stuck in the receiver. This can be caused by playing with too much pressure, when the player forgets to clean the moisture from the mouthpiece, or when the player forgets to take out the mouthpiece after playing. If it becomes stuck, it is essential to use the specially designed tool to remove it— a mouthpiece puller, that will separate the mouthpiece from the receiver without damage to the mouthpiece or pipe. Brass players call wrong notes CLAMS!

(3) Cellists may jam the sharp end of the endpin into a wooden floor, making a hole, which doesn’t please stage-managers. There are several implements available to “hold” or anchor the spike/endpin in place. These range from pucks to straps. But sometimes these slip too! Carrying the cello should be enough, but chairs are often too low. Hence bringing a wedge seat cushion.

(4) The wolf is an undesirable phenomenon that occurs on some bowed string instruments, especially on the cello. When the pitch, often an F# on the G string, is played and it is closely related to a natural, resonant frequency of the instrument, the instrument will vibrate intensely. It can be difficult to control and can sound strange, like a stuttering or warbling. Some cellists resort to a wolf tone eliminator—a small metal tube with a screw mounted on one of the strings below the bridge. They don’t work reliably. I used to squeeze my cello with my knees to reduce the vibration of the instrument and this sometimes worked. But it can still sound like a howling WOLF!

(5) Leger line is used in western musical notation. They are short lines that extend above or below the staff, placed parallel to the lines of the staff, and equidistantly spaced to denote higher or lower notes beyond the staff. Try reading these with progressive glasses or when you haven’t had enough sleep!

(6) Tristan Schulze wrote “Resurrection of the Viola Player” to be played by Julian Rachlin on the viola. This is the very first piece that Julian ever played on the viola, and he had to learn it for memory because he did not know the viola cliff well enough at the time! With violinist and comedian Aleksey Igudesman, Daisy Jopling, violin, Tristan Schulze, cello.