It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, November 29, 2024

𝗛𝗮𝗽𝗽𝘆 𝗕𝗶𝗿𝘁𝗵𝗱𝗮𝘆, 𝗦𝗶𝗿 𝗥𝗲𝘆! ❤️

Bringing Folk Music to Life: Grieg’s Lyric Pieces

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

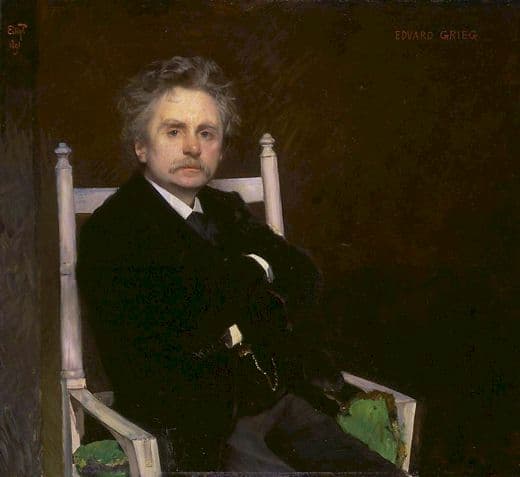

Eilif Peterssen: Edvard Grieg, 1891 (Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet)

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) was born in Bergen, Norway, and when his skills were recognised by the violinist and composer Ole Bull, he was sent to Leipzig at age 15 to attend the conservatory. Although he later complained about the conservatory, there is no doubt that he received very good and solid musical training. In a city with an extremely active musical life, he heard music he never would have encountered in Norway and it made a lasting impression on him.

When he returned to Scandinavia, he first went to Copenhagen and there started to make his name as a composer. Meeting the Norwegian composer Rikard Nordraak, Grieg came to believe, as Nordraak did, that the future of Norwegian music lay in nationalism and that folksong was key to this.

In 1866, Grieg returned to Norway and settled in Christiana, a part of the capital city of Oslo. Although he wrote many major works, his identity with folk music tainted his reputation as someone who simply borrowed from folk music. Grieg’s own compositional style followed that of traditional Norwegian music: ‘Much instrumental Norwegian folk-music is built from small melodic themes, units which are repeated with small variations in appoggiaturas and sometimes with rhythmic displacements’. Development sections are rare. In following this style, he made it difficult for listeners to tell the difference between his original works and folk music borrowings.

The rise of the piano (it’s estimated that in 1910, more than 600,000 pianos were produced) gave Grieg a ready audience for his piano pieces. They were so popular that his publisher, C.F. Peters in Leipzig, eventually gave him an annual salary for the right to have first choice of his new works.

In his collections of Lyric Pieces, there were eventually 66 works published in 10 albums in the 34 years between 1867 and 1901. His fifth book, Op. 54, published in 1891, is considered to contain his best work in the series. The idea of Nature binds the collection together, and the source material is Grieg’s own, not coming from folk music.

The fourth piece in the collection, the March of the Trolls, takes the equivalent of the Norwegian boogieman as its subject. When the irritable, short-tempered trolls come out after dark with their plans to wreak havoc on quiet households everywhere, beware!

This piece, originally for piano, was orchestrated by conductor Anton Seidl for the New York Philharmonic as part of a work he called Norwegian Suite. This was later revised by Grieg as Lyric Suite with one piece removed, another added, and the order shifted. Grieg’s revised version replaced Seidl’s original version, which is rarely heard anymore.

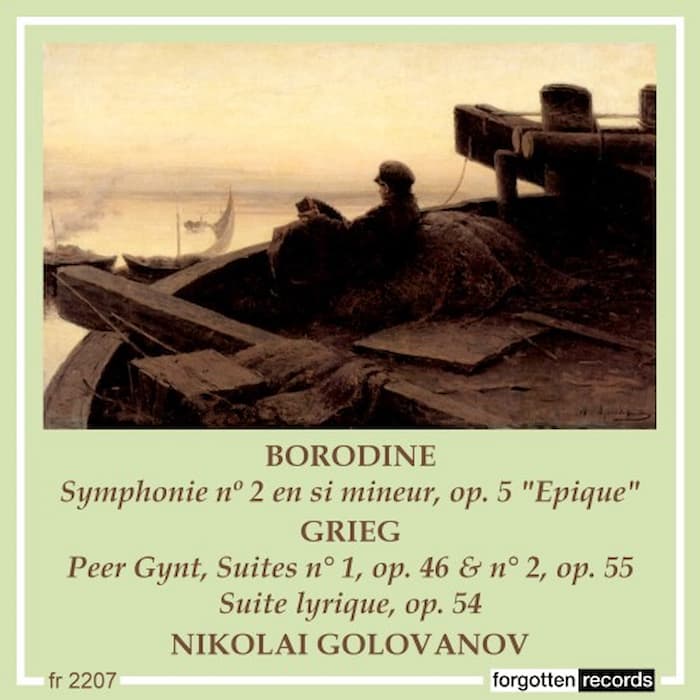

Golovanov (R) and Shostakovich (L)

This recording was made in Moscow in 1949, with Nikolai Golovanov leading the Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio de l’URSS. Soviet composer and conductor Nikolai Semyonovich Golovanov (1891–1953) was one of the leading conductors of his time, and was extensively associated with the Bolshoi Opera. He was recognised as a People’s Artist of the USSR and Honoured Artist of the RSFSR, was awarded the Stalin Prize Winner four times, and was also awarded the Order of Lenin, Order of the Red Banner of Labor, Medal ‘For the Defence of Moscow’ and Medal ‘For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945’. He was dismissed by Stalin over a disagreement about casting a Jewish singer for the title role in a recording of Boris Godunov. His friends said it was his shame over this dismissal that led to his death.

Performed by

Nikolai Golovanov

Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio de l’URSS

Recorded in 1949

Why Are We More and More Attracted to Slow Music?

by Doug Thomas, Interlude

Ludovico Einaudi © Decca/Ray Tarantino

Over the past fifty years, there has been a rise of interest for this type of music, and more people seem to be attracted to it — whether they are the creators or the listeners. It seems it has become the backdrop of many people’s off-time, too. Some would say it is by necessity, a counter-reaction to the busyness that our lives are now stuck into, and others would say it is by taste. Whatever the reason is, it is definitely there and growing more and more.

Ryuichi Sakamoto – Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

Bryars, Richter, Einaudi, Pärt, Sakamoto or Frahm and Arnalds. All these composers, in their own ways and through their works, started or participated in launching a considerable wave of smaller, lesser-known — and often amateur — musicians and composers whose mantra has been to slow down, turn the dynamics down and reduce the musical information. These composers have written the soundtracks of our modern-day workspaces. They are in the background of our offices, in public spaces, in our apps, in our TVs and in our films. And even at times, they are the music which we play while we sleep. They are often unknown or unrecognised. But they represent a lot of the music which is present in our daily lives. If there is a meditative and relaxing element to this music being created, it is not emerging from a new age or spiritual intention, but rather the wish to offer an alternative to the busy lives that we all live and allow art — once again — to provide an escape to reality.

Brian Eno: There Were Bells

Of course, one cannot mention slow music without venturing into the world of ambient music, and particularly the impact of Eno who has been a pioneer in this genre. With his work on ambient music, Eno has allowed composers to accept the slowing down of pace and slow musical development, and through the works of the minimalists, the focus on smaller structures and simpler concepts. His influence can be felt in current composers today; a great example of that is Richter and his Sleep project. The downside to the phenomenon of slow music is that it seems that all of it ends up being the same. Slow and calm music is based on simpler structures and less musical devices being used. Therefore the sense of repetition between works and artists appears quicker, and many composers fail to produce truly original music, and often it appears as paper copies of the original artist. The rhythmic, melodic and harmonic language is often the same, and there is not much space for exploration. In other words, it sometimes seems like a lot of quiet noise, which no one really wants to pay attention to.

Ludovico Einaudi – Nuvole Bianche (Live From The Steve Jobs Theatre / 2019)

The attention span of the human brain seems to have decreased, and therefore, it would seem that busy and complex music is rejected in favour of simpler, more balanced music –– who wants to listen to Wagner today? The function of music must have changed a lot too, and many people perceive it as a sound decoration rather than a proactive act of listening. And therefore a calmer, quieter tapestry of sound works better than a busy and stimulating musical work. It has taken, like Satie foresaw, a decorative element to our life. One must ask though; is it also that we are less educated to music than we were before? The times before the invention of the radio and the television asked for people to learn how to perform their own music for their own enjoyment. Or perhaps the fact that music is so omnipresent in our lives — it is hard to spend a day without hearing some form of music — affects how we want to experience music when it is intentional — and perhaps less busy.

On This Day 29 November: Giacomo Puccini Died

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Giacomo Puccini in Torre del Lago, where he lived for thirty years

Like his colleagues before, the physician discovered nothing suspicious beyond a slight inflammation deep down the throat. He advised Puccini to take a complete rest, abstain from smoking and come back in fourteen days. While his family was clearly relieved, Puccini knew that things weren’t right.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Tu che di gel sei cinta”

Unbeknownst to his family, Puccini consulted yet another specialist in Florence who diagnosed a “walnut-sized advanced extrinsic cancer of the supraglottis.” Tonio refused to accept the diagnosis but was told in no uncertain terms that his father was suffering from cancer of the throat in so advanced a stage that an operation would be futile. After consulting a number of eminent specialists, it was suggested that treatment by X-ray “was the only method likely to arrest the rapid progress of the disease.”

Puccini in 1924

As this kind of treatment was in its infancy, there were only two clinics in all of Europe where the method had been tried out with some success. Puccini decided to consult Dr. Ledoux in Brussels, and he wrote to his librettist Adami on 22 October 1924, “I am leaving soon… Will they operate on me? Shall I be cured? Or condemned to death? I cannot go on like this any longer. And then there is Turandot… Puccini departed for Brussels on 4 November 1924, taking with him sketches for the love duet and the finale of the last act, thirty-six pages in all.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Nessun dorma”

The first part of the experimental treatment saw Dr. Ledoux place a collar containing radium around Puccini’s neck. Puccini reports, “I am crucified like Christ! External X-ray treatment at present—then crystal needles into my neck and a hole in order to breathe… What a calamity! God help me. It will be a long treatment, six weeks, and terrible.”

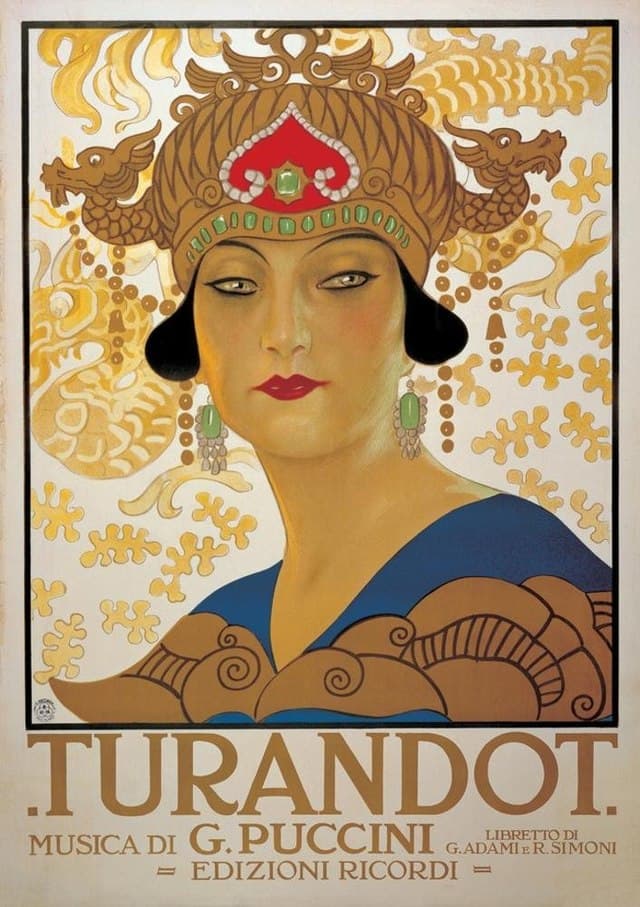

Poster of Turandot‘s performance

During his initial treatment stage, Puccini was not confined to bed but was allowed to leave the clinic. He went to see a performance of Butterfly at the Theatre de la Monnaie, and his clinical condition improved. Puccini visited the local markets and went out for luncheons, and he started smoking again. The second part of the treatment commenced on 24 November, when seven needles were inserted into the tumor in an operation that lasted three hours and forty minutes. Although Puccini suffered agonizing pain, Dr. Ledoux was apparently satisfied that Puccini would pull through.

Memorial plate of Puccini

Unexpectedly, however, Puccini collapsed in the evening of 28 November and he died of heart failure at 4 am on 29 November 1924. A biographer writes, “Dr. Ledoux was so shattered by this sudden turn of events that, driving home in his car afterward, he is said to have fatally injured a woman pedestrian.”

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Del primo pianto si, straniero”

When news of Puccini’s death reached Rome, a performance of La Boheme was stopped, and the orchestra spontaneously played Chopin’s “Funeral March.” The funeral ceremony took place on 1 December in Brussels, and mourners silently lined the street from the clinic to the Church of Ste Marie. When Mme Laure Berge sang Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” a wave of emotion “rippled through the crowd outside the church as the public wanted to share their sorrow for the loss of a famous and very loved Maestro.”

Statue of Giacomo Puccini in Lucca, Italy

Puccini’s body was taken to Milan two days later. Toscanini and the Scala orchestra played the Requiem music from Edgar. Amid torrential rain Puccini’s mortal remains were then conveyed in a solemn procession to the Cimitero Monumentale for provisional burial in Toscanini’s family tomb. On the day of the second anniversary of his death, the coffin was brought to Torre and placed in “the mausoleum, which Tonio had erected in the villa by the lake. Pietro Mascagni spoke the funeral oration, and the conductor Bavagnoli and an orchestra performed music from Puccini’s operas. As for Turandot, Franco Alfano was commissioned to complete the score, a task that took him roughly six months.

Thus Spoke Friedrich Nietzsche: Piano Music

by Georg Predota, Interlude

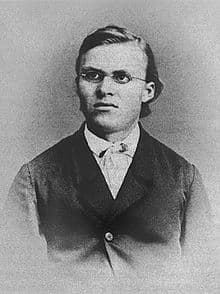

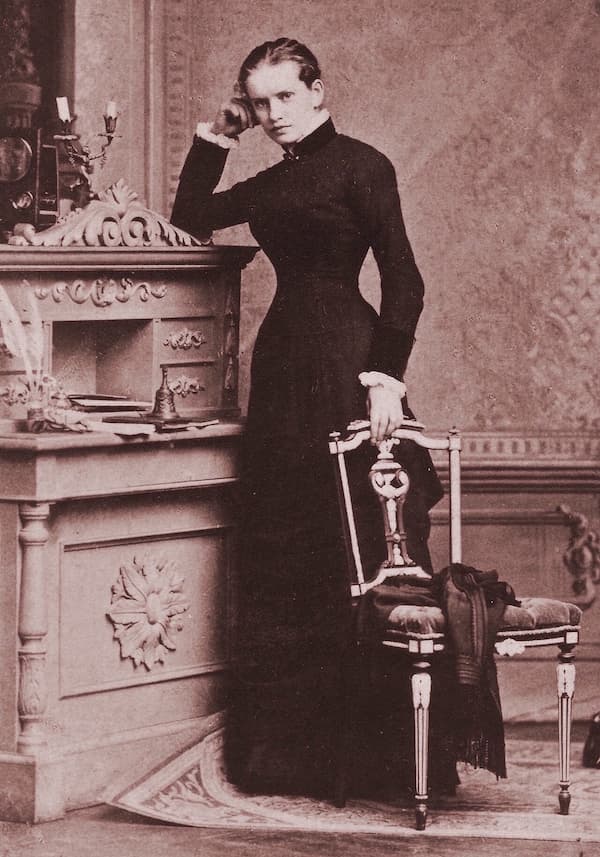

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche at 21

Essentially, Nietzsche questioned the value and objectivity of truth, looking at God as a historical process and construct. Nietzsche wrote numerous texts on morality, contemporary culture, philosophy and science. Interestingly, he never really trusted the written word. He wrote, “all communication through words is shameless. The word diminishes and makes stupid; the word depersonalises, the word makes what is uncommon common.”

It might come as a surprise, but music was actually Nietzsche’s true love. Descended from a family of pastors where music and theology went hand in hand, young Friedrich was an accomplished pianist and organist by the time he reached the age of seven. At that age, he already played several Beethoven sonatas, transcriptions of Haydn Symphonies, and he was skilled in the way of improvisation. A couple of recent recordings have engaged with Nietzsche’s piano compositions, so we decided to take a closer look.

Reminiscences on my Life

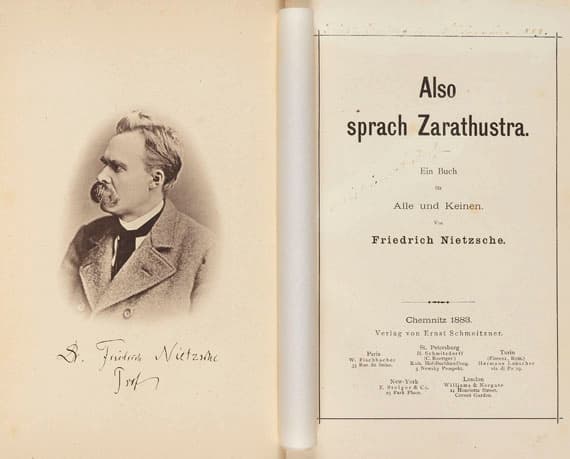

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Young Nietzsche initially improvised his own melodies, yet he soon moved on to sketch motets, symphonies, masses and oratorios, most of them unfinished. As he grew up, Nietzsche switched to smaller forms, particularly Lieder and piano pieces. As pianist Jeroen van Veen writes, “these pieces reflect the philosopher as a human being, vulnerable and desirous, but above all melancholic.”

At the age of 14, Nietzsche wrote his “Reminiscences on my Life.” He explained, “All qualities are united in music: it can lift us up, it can be capricious, it can cheer us up and delight us, nay, with its soft, melancholy tunes, it can even break the resistance of the toughest character.”

“Its main purpose, however, is to lead our thoughts upward so that it elevates us and even deeply moves us. All humans who despise it should be considered mindless, animal-like creatures. Let music, this most marvellous gift from God, remain forever my companion on the pathways of life.”

Barbarous Frenzy

In his “Reminiscences on my Life,” Nietzsche carefully listed his writings and his compositions, and at age fourteen, he had 46 compositions to his name. The earliest Lieder settings of Klaus Groth, the Hungarian poet Sándor Petöfi, Pushkin and Hoffmann von Fallersleben, were all composed “in a kind of barbarous frenzy, as the demon of music took hold of me.”

Nietzsche never took composition lessons, as he was essentially self-taught. He described himself as “a wretched youth who tortured his piano to the point of drawing from it cries of despairs, who with his own hands heave up in front of himself the mire of the most dismal greyish-brown harmonies.”

The Germania

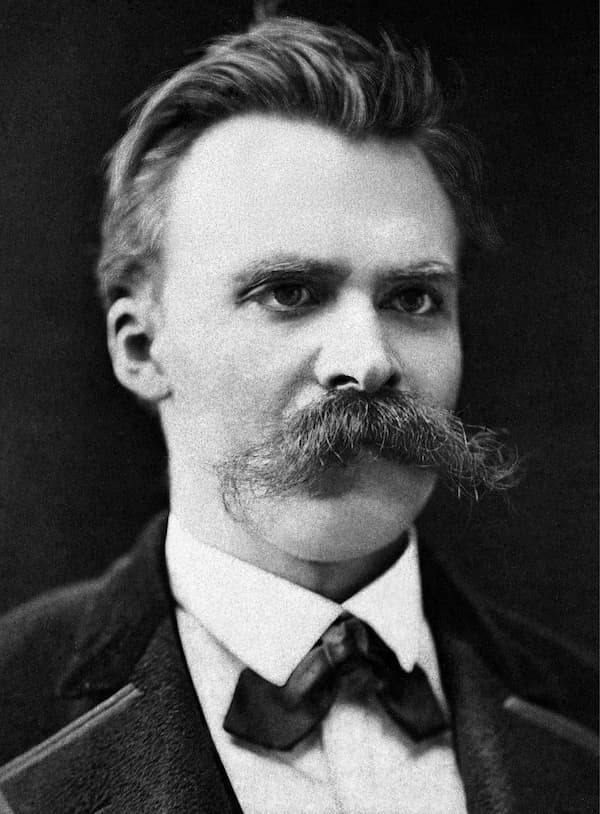

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

At the age of 16, Nietzsche started on a Christmas oratorio that was never finished. However, he would develop several themes for later use in subsequent compositions. “I look for words for a melody that I have and for a melody for words that I have, and these two things I have don’t go together, even though they come from the same soul. But such is my fate.”

Nietzsche’s early piano music is frequently dedicated to family and friends. Together with two young friends, he founded a small society called “The Germania,” which was dedicated to the “development of the spirit.” They would send each other compositions and poems, lectures and articles. And Nietzsche loved to improvise. A fellow student listened to these improvisations and wrote, “I should have no difficulty in believing that even Beethoven did not play extempore in a more moving manner.”

Assessment

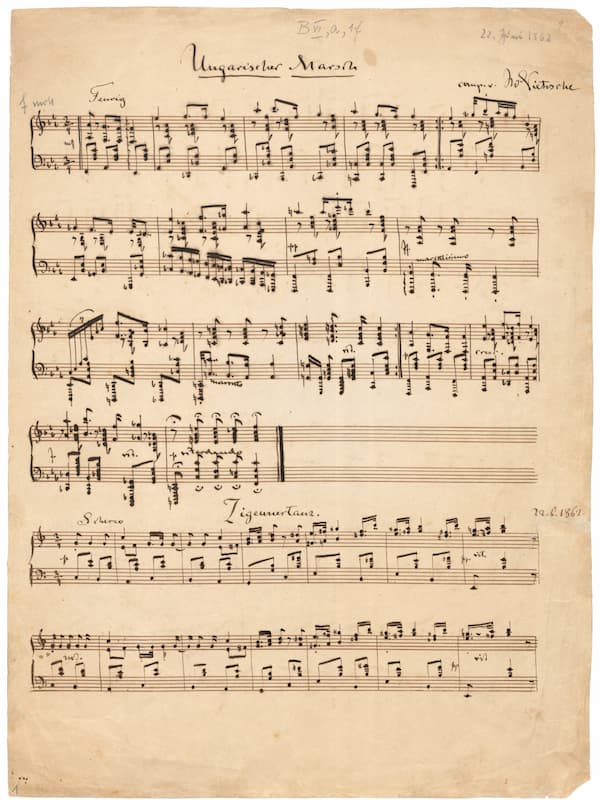

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Hungarian March

However, assessment from professional sources was less encouraging. Nietzsche sent Hans von Bülow, son-in-law of Richard Wagner, his “Manfred Meditation” for evaluation. Bülow was not impressed and wrote, “this music is the most extreme in fantastic extravagance and the most unsatisfying and most anti-musical composition I have seen in a long time. Is this a joke that deliberately mocks all rules of tonal harmony, of the higher syntax as well as of ordinary orthography?”

“In musical terms, this piece is the equivalent to a crime in the moral world, with which the musical muse, Euterpe, was raped. If you would allow me to give you some good advice, just in case you are actually serious with your aberration into the area of composition, stick with composing vocal music, since the word can lead the way on the wild sea of tones. I apologize, esteemed Herr Professor, of having thrown such an enlightened mind as yours, into such regrettable piano cramps.”

Lou Salomé

Lou Salomé

Nietzsche’s “Hymn to Life” is based on a text by Lou Salomé, a Russian-born psychoanalyst, well-travelled author, narrator, and essayist. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé met the author Paul Rée, who instantly proposed to her. Salomé declined and suggested setting up an academic commune, which was joined by Nietzsche in April 1882. He instantly fell in love with her as well, but she rejected him twice. Instead, Salomé, Rée, and Nietzsche travelled in search of setting up their commune in an abandoned monastery, but as no suitable location was found, the plan came to naught.

We do find an interesting assessment of Nietzsche by Salomé, which reads, “The higher he rose as a philosopher in his exaltation of life, the more deeply he suffered, as a human being, from his own teachings about life. This battle within his soul, the true source of the philosophy of his last years, is only imperfectly represented in his words and books, but it sounds perhaps most profoundly through his music to my poem Hymn to Life.”

Sabbatical

After completing the “Hymn of Life” and receiving Bülow’s devastating letter, Nietzsche wrote, “As for my music, I only know that it allows me to master a mood that unsatisfied, would perhaps produce even more damage. If music serves only as a diversion or a kind of vain ostentation, it is sinful and harmful. Yet this fault is very frequent; all of modern music is filled with it.”

After receiving this letter, Nietzsche did not touch his piano for a while, but in the end, “his awareness of being an amateur was overshadowed by his urge to become a better person, through music,” writes Vrouwkje Tuinman. As Nietzsche frequently proclaimed, “Emotions, morals, the world: the only way to (maybe) grasp the essence of being is surrendering to the highest of art forms,” he writes again and again. “Without music, life would be a mistake.”

The Affair Wagner

Richard Wagner

During his time as Professor of Philosophy at Basel University, Nietzsche became a close personal friend of Cosima and Richard Wagner, then living in Swiss exile. He was a regular house guest and even had his own room at Tribschen. We know that Nietzsche fell in love with Cosima Wagner, and he certainly composed some music for her.

Nietzsche dedicated his first book, “The Birth of Tragedy” to Wagner, proclaiming Wagner’s music the modern rebirth. The first part of the book was developed from long conversations between Cosima, Wagner and Nietzsche, roughly around the same time that Wagner began to develop the story of what eventually would become the “Ring Cycle.”

Postlude

Cosima Wagner

Nietzsche offered Richard and Cosima his “Reminiscence of a New Year’s Eve,” but they basically ignored it. In turn, Nietzsche started to object to Wagner’s “endless melody,” suggesting that listening to Wagner’s music made his whole body feel discomfort. He called it “a music without a future,” and that the effects of Wagner’s music are “for idiots and the masses.”

Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown at the age of 44, from which he never recovered. For the last eleven years of his life, he was no longer able to speak or write, but he continued to play the piano. Listening, performing and composing music became an unconscious philosophical activity for Nietzsche, who had suggested earlier that “sound allowed me to say certain things that words were incapable of expressing.”

Editors of Nietzsche considered his compositions “amateurish and lacking in originality.” However, composing for Nietzsche meant experimentation and therapy, as he famously wrote, “we have art so not to die from the truth.” His piano music continues to be explored, and scholars write that “these piano miniatures present a fascinating window into the creative mind of a still-lofty figure in Western thought.” To me, his piano music, an elaboration of the conflicted world of Schumann, sounds hesitant and even unguarded, and the occasional ray of optimism is quickly cast aside by all-pervasive melancholy.

Thursday, November 28, 2024

Why do orchestras have ‘leaders’ and what do they do?

By Will Padfield

One of the most elusive figures of the orchestra is the leader – or concertmaster. But what’s their role, and when did it start?

An orchestra can be a baffling organism to comprehend. The way it is arranged, structured and managed has evolved over centuries to arrive at its present-day set-up.

To anyone who isn’t in the know, one of the most cryptic figures of the orchestra is the leader – or concertmaster. Outranked only by the conductor, this musician is responsible for good relations between the orchestra and maestro, acting as an intermediary and ensuring all goes smoothly.

They sit at the front of the orchestra, direct everyone in tuning their instruments, and have their very own applause on entry to the concert stage.

But what are the origins, development and function of this mysterious being? We delved into the history...

When was the concertmaster position invented?

The role of the concertmaster has evolved throughout the ages, changing as orchestral music expanded and became increasingly complex. In the Baroque era (roughly 1600-1750), composers such as Bach and Vivaldi firmly cemented the prominence of the violin family as the de facto leading voice of an ensemble, writing music with prominent lead violin parts, often with demanding solos.

In the days before the conductor was a regular fixture of an orchestra, the concertmaster, or ‘lead violinist’ would usually direct the ensemble and play simultaneously, using the movements of the bow to keep time. At this time, there was no standardised position of ‘leader’, and the mechanics of ensemble leadership varied greatly between countries.

During the mid- to late-18th century – known as the Classical era – orchestras expanded even further, with wind and brass sections gradually becoming permanent fixtures in orchestras. With a larger group of musicians, there became an even greater need for a clear leader to create (literal) harmony between all the musicians in the ensemble.

The principal violinist emerged as the logical figure to take on this demanding role, responsible for leading the string section, creating a cohesive sound and, crucially, keeping everyone playing in time!

Beethoven Symphony No. 5 - Academy of St Martin in the Fields & Joshua Bell

Just as the leader started to take full control over orchestral proceedings, the title was contested by the emergence of the conductor in the latter half of the classical period. Again, the nuances of history mean this change didn’t happen overnight, but by the mid-19th century, the Romantic era was in full swing, and the leader’s role had morphed more into the one we recognise today.

During this period, music became increasingly expressive, and orchestras expanded even more. The concertmaster became essential in determining the sound of an orchestra and making their own interpretive decisions in rehearsals. Composers often wrote virtuosic solos for the leader, where the violinist needed to seamlessly adapt from sitting as part of the section to stepping up to the main solo voice for a passage.

Anton Sorokow - Richard Strauss "Ein Heldenleben" Violin Solo

What does a concertmaster do today?

Today, the position of concertmaster is highly revered, with the major orchestras offering highly lucrative sums of money to employ the very best violinists. The crucial role of the leader is to set the very highest standards of musicianship for the other musicians to follow.

A good leader elevates the level of an orchestra, and a bad one can have disastrous consequences for everyone involved. Aside from being a superlative instrumentalist, a substantial part of the leader’s role is managing the occasionally fragile relationship between the conductor and the ensemble.

Conductors are often jet-setting between orchestras – with the most successful of them conducting orchestras across several continents in the same month – but the concertmaster is a fixed member of their orchestra.

A good leader will have the best read on the interpersonal relationships between the musicians and can empathise with the members of the orchestra, who may be tired after a particularly trying schedule or a tour, and communicate this to the conductor. It is also the leader’s responsibility to ensure rehearsals are conducted in a mutually beneficial way, stepping in to stop rehearsal chatter (believe it or not, this happens…) where it would be unwise for the conductor to issue a warning.

Brahms: Symphony No. 1 / Blomstedt · Berliner Philharmoniker

Fundamentally, the concertmaster is a vital link between the conductor and the orchestra. They help translate a conductor’s gestures into actual playing technique, which is then copied by the entire string section, hugely influencing the collective sound of the ensemble.

Perks of the job

One of the most recognisable roles of the leader is to indicate when it is time for the orchestra to tune by standing and gesturing to the oboist, who gives the tuning note (an A).

In the UK and USA, the leader will walk on separately to the rest of the musicians and take a much-served show of appreciation from the audience. As a mark of respect, the leader is the first to leave the stage, with the orchestra filing in behind off stage.

So, there you have it! The next time you are at a concert, spare a thought for the leader and all the hard, and oft-underappreciated work they do to keep the orchestra functioning.