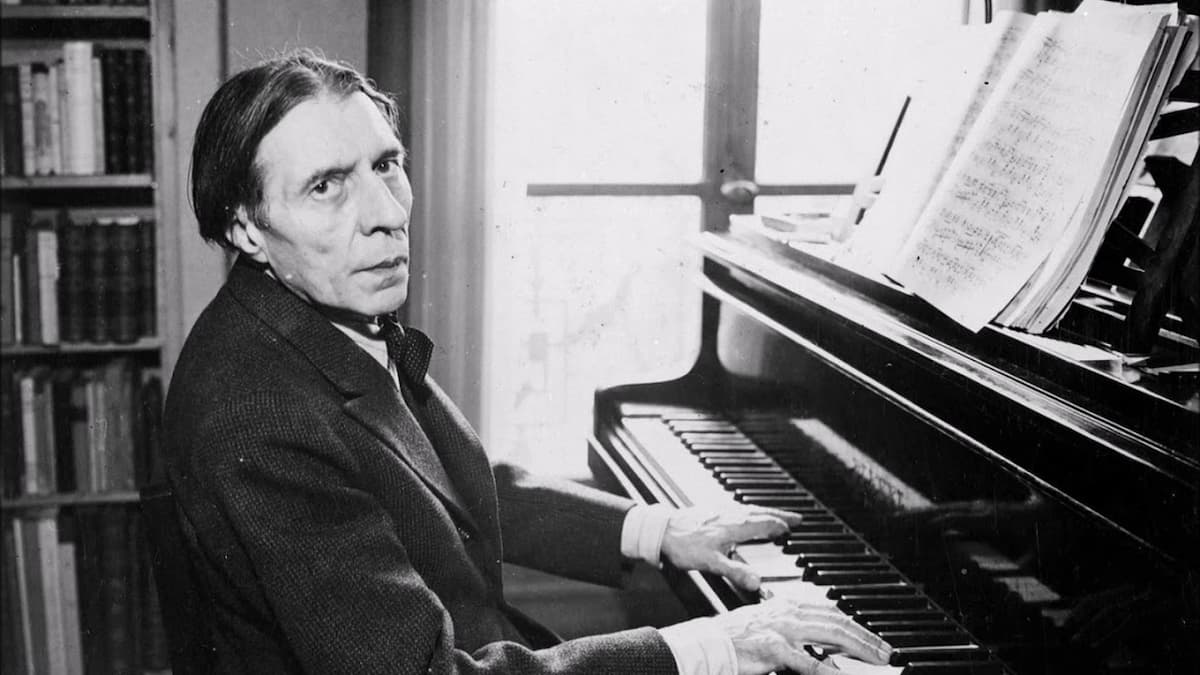

Gabriel Fauré © Pianodao

Stylistic developments none withstanding, Fauré developed his individual voice from his handling of harmony and tonality. Drawing on rapid modulations, he never completely destroyed the sense of tonality, always aware of its limits, yet freeing himself from many of its restrictions.

Fauré’s harmonic richness is complemented by his melodic invention. As Jean-Michel Nectoux writes, “he was a consummate master of the art of unfolding a melody: from a harmonic and rhythmic cell he constructed chains of sequences that convey, despite their constant variety, inventiveness and unexpected turns an impression of inevitability.”

Concurrently with his songs, chamber music constitutes Fauré’s most important contribution to music. The elegance, refinement, and sensibility of his melodic writing easily transferred into the instrumental realm. On the 100th anniversary of his death, let us celebrate Fauré’s highly developed sense of sonorous beauty by exploring his magnificent and highly popular compositions for the cello.

Let’s get started with one of the most beautiful and popular pieces by Gabriel Fauré, the Sicilienne, Op. 78. The work actually has an interesting history, as Camille Saint-Saëns was asked by the manager of the Grand Théâtre to compose incidental music for a production of Molière’s “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme.” However, Saint-Saëns was rather busy, and he recommended his former student Gabriel Fauré for the task.

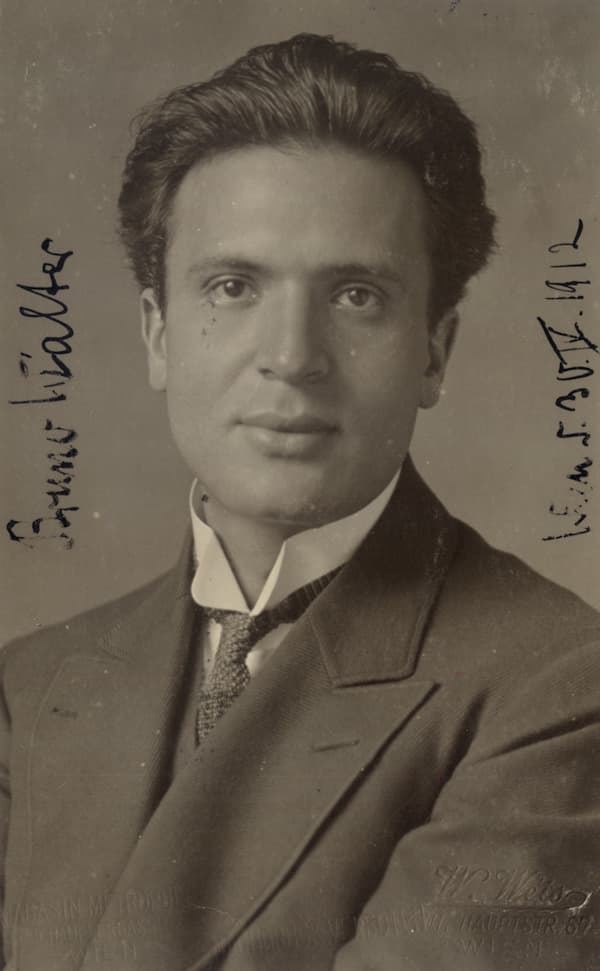

Portrait of Camille Saint-Saëns by Benjamin Constant

Fauré went to work, and the music was nearly complete when the theatre company went bankrupt in 1893. The production was abandoned, and the music, including the first version of the Sicilienne, remained unperformed. Five years later, Fauré was engaged to write incidental music for the first English production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, Pelléas et Mélisande. Fauré would eventually publish a suite derived from this incidental music, which included an updated and orchestrated version of the Sicilienne.

Concordantly, however, the Dutch cellist Joseph Hollman, who frequently appeared in concert with Camille Saint-Saëns, was looking for a short encore. As such, Fauré fashioned an arrangement for cello and piano and dedicated the piece to William Henry Squire, a British cellist and principal with several major London orchestras. This most famous and memorable melody builds from a delightful lyrical theme in the minor mode. It evokes a pastoral mood with its lilting rhythms, and it has since been arranged for countless combinations of instruments.

The two sonatas for cello and piano by Gabriel Fauré belong to his final creative period. The first sonata was composed in Saint-Raphaël, where Fauré liked to seclude himself far away from the hustle and bustle of Paris. Written between May and October 1917, the work echoes the unsettling dark days of the First World War. To be sure, Fauré’s younger son Philippe was in the army, and the A-minor sonata seemingly reflects the composer’s anxiety and apprehension.

Fauré’s older son Emmanuel suggested that the uncharacteristically aggressive tone of the composition also represents his father’s anger at his worsening deafness. Like much of his chamber music from this period, Fauré was searching for harmonic and contrapuntal freedom, “and the rarefied and austere character is reinforced by concentrated writing for the instruments.”

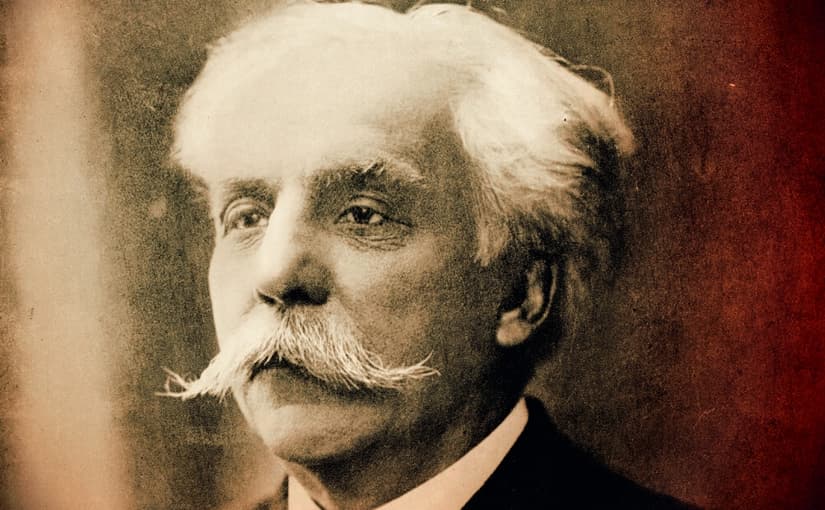

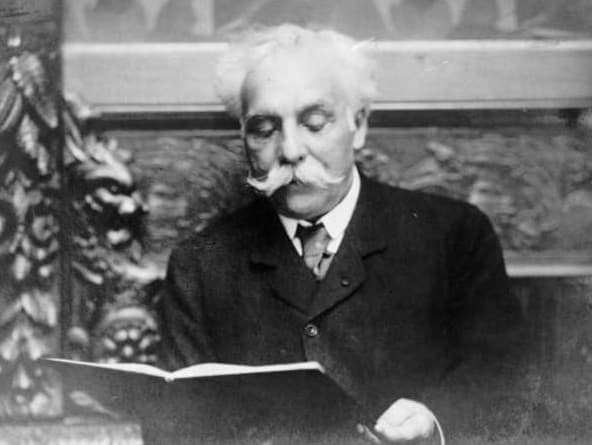

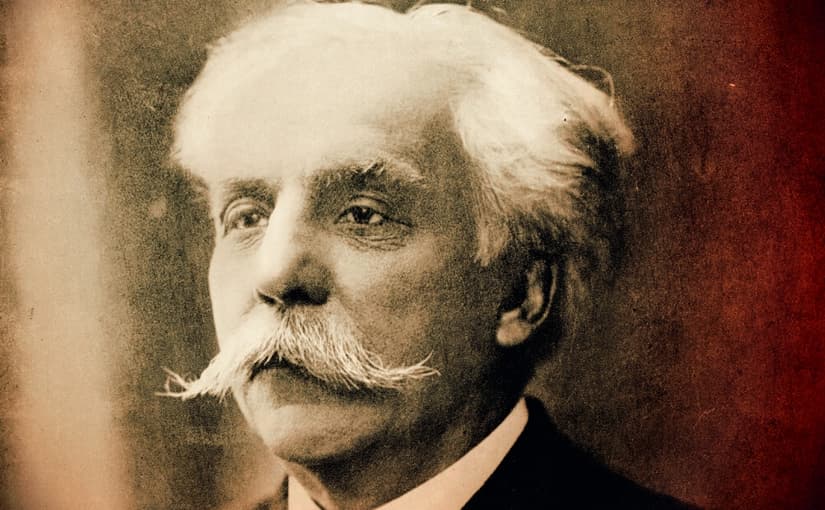

Gabriel Fauré in 1907

The opening “Allegro deciso” launches into a violent theme from a discarded symphony and also from the music of his warlike opera Pénélope. The lyrical contrast is short-lived, and the fiery ending features new unsettling piano figuration. Essentially a restless nocturne, the central “Andante” was the first movement to be composed. The music offers echoes from his Requiem, and the search for tranquillity is continued in the concluding “Allegro comodo.” However, brief glimpses of optimism are subdued by strict contrapuntal severity.

Gabriel Fauré had a complicated relationship with the publisher Julien Hamelle. Hamelle was a shifty character who frequently lost manuscripts, and as he was severely “forgetful,” he was not particularly reliable. Always looking for quick sales, Hamelle loved to add fanciful titles to Fauré’s compositions. Such was certainly the case for the French “Flight of the Bumblebee” he commissioned from Fauré. This virtuoso miniature was composed in 1884 but only published fourteen years later, in 1898.

Hamelle insisted on first calling the piece Libellules (Dragonflies), then Papillon (Butterfly). Fauré was never enamoured with fanciful titles, and he angrily wrote back, “Butterfly or Dung Fly, call it whatever you like.” Fauré did insist, however, that the words “Pièce pour violoncelle,” a title more suited to his aesthetic approach, should appear as a sub-title.

Scored in five sections, it is a piece of pure virtuosity in the outer framing pillars. The middle episodes, however, contain the most beautiful lyrical passages. This gorgeous symmetrical song, as a commentator writes, “finally takes wing over one of Fauré’s favourite descending bass lines.” In the end, Hamelle was correct in appending a fanciful title as Papillon became incredibly popular with cellists from around the world.

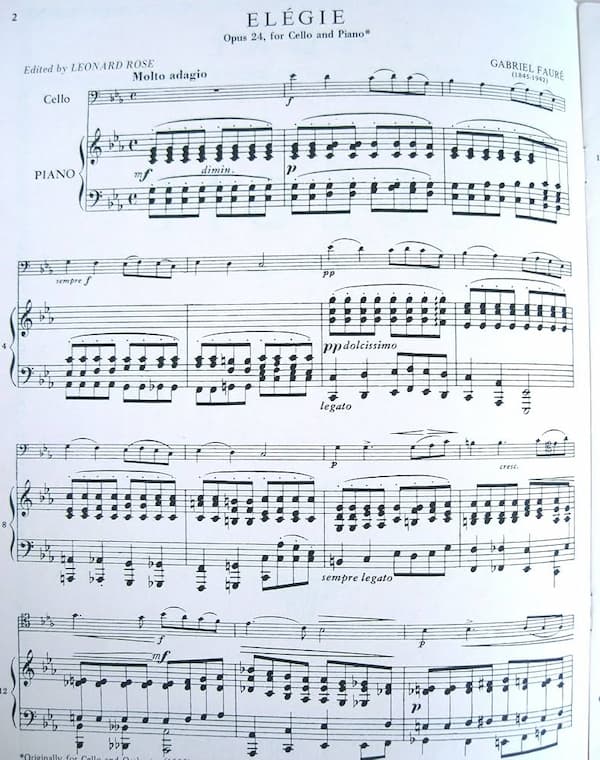

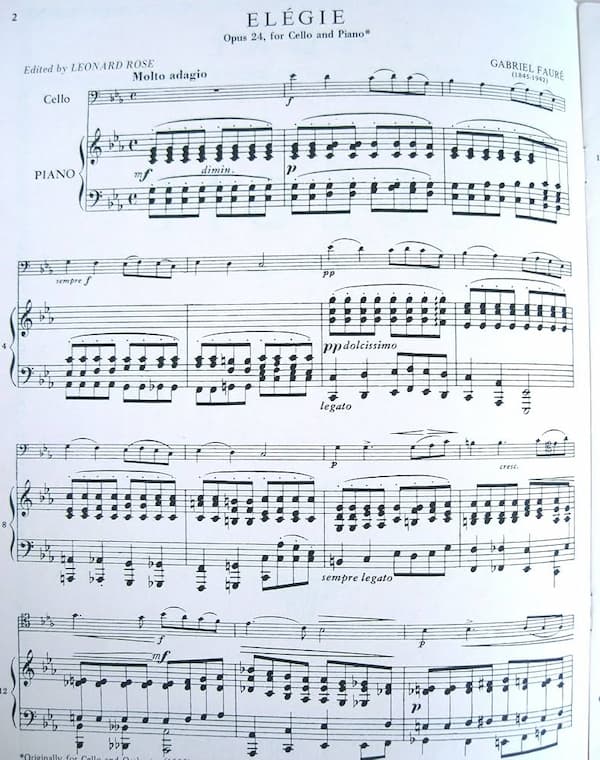

Fauré’s Papillon was actually a commissioned pendant for his already highly popular Élégie. That particular gem emerged in 1880 after the composer had finished a violin sonata. Fauré had decided to write a counterpart for the cello, and habitually, he started with the slow movement. When he played it for his friend and mentor Camille Saint- Saëns, his teacher was overjoyed. Work on the sonata progressed no further, but the slow movement with the title “Élégie” was published in 1883.

Gabriel Fauré’s Élégie, Op. 24

For Patrick Castillo, “the compact frame, its brevity, intimate scoring…belies its expressive range. The work seems to honour grief as a multifaceted thing and depicts it as such. Herein lies Fauré’s mastery. He possesses the sensibility to probe, with economy and exquisite subtlety, the depth of human emotion, giving graceful voice to our innermost feelings.”

Scored in three sections, the C-minor opening is reminiscent of a funeral march supported by a solemn progression of chords on the piano. As the middle section modulates to the major key, the music becomes more lyrical and melancholic. A sudden tortured outcry returns us to the opening melody, now transformed and supported by a flurry of notes in the piano.

The Berceuse, later to become part of the Dolly Suite, damaged Fauré’s reputation for a very long time. Let me explain. It actually dates from his student years and was composed in 1864. It was originally titled “La Chanson dans le jardin,” and written for Suzanne Garnier, the daughter of a friend. The initial scoring called for violin and piano, but once it was published, the title page provided the option “for violin or cello.” In the event, this tender little piece caused Fauré to be known as a “salon composer,” a reputation that proved incredibly difficult to shake.

When Fauré first met Emma Bardac, she had recently given birth to a daughter, Hélène, nicknamed Dolly. Emma was married to a banker and Gabriel to Marie, and their affair lasted the better part of four years. Emma was his intellectual equal; she was outgoing, amusing, articulate, and exuded great warmth from the mothering side of her personality. After their affair ended, Emma met Debussy, and after eloping to England, the two got married.

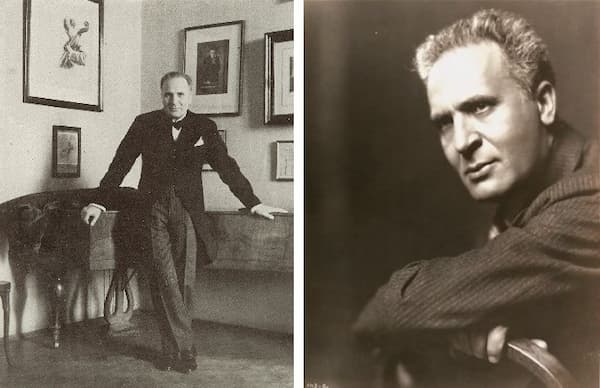

Emma Bardac-Debussy

In the 1890s, Fauré composed or revised small pieces, especially for Dolly. These pieces celebrated a birthday, a pet, or various friends of the little girl. Combining six of these miniatures, Fauré produced the “Dolly Suite” for piano duet. The Berceuse marked Dolly’s first birthday in 1893. This dreamy lullaby rocks the cradle with a swinging accompaniment, a music-box texture, and charming harmonic transparency.

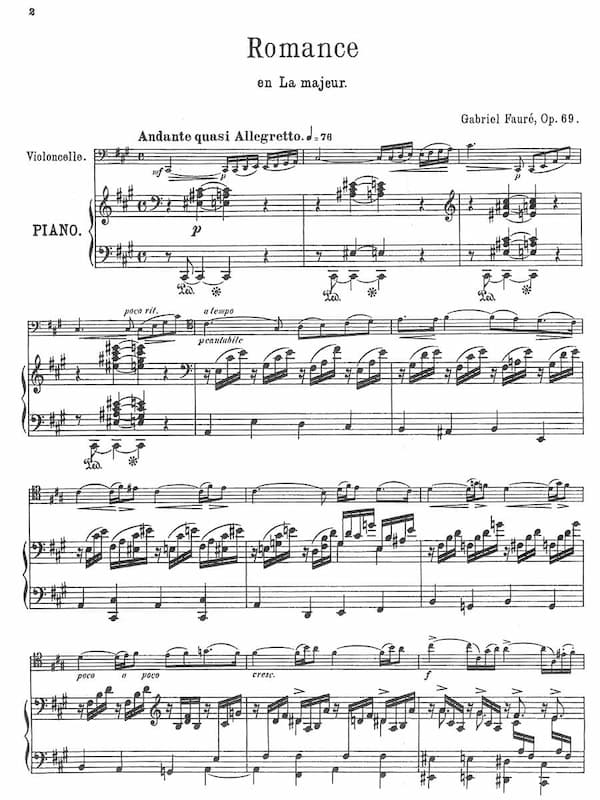

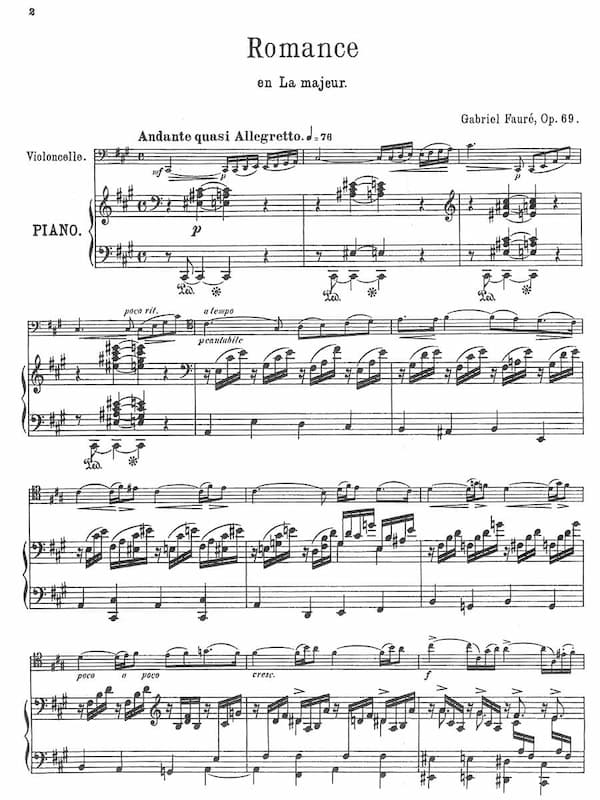

Romance

During his time as organist at the Église de la Madeleine in Paris, Fauré composed a short piece for organ and cello simply titled “Andante.” For unknown reasons, the composer delayed publication until 1894, but eventually adapted the original organ part for the piano. He changed the tempo from “Andante” to “Andante quasi allegretto” and appended the title “Romance.”

Gabriel Fauré’s Romance, Op. 69

The sustained organ chords became arpeggios, but the solo part remained essentially unchanged. This wonderful miniature places great emphasis on lyricism as the music grows into a long and flexible phrase. The principle theme is not new, as Fauré had already used it in his incidental music for Shylock, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. And you might also recognise it from his song “Soir,” a setting of a poem by Albert Samain.

Sérénade

The last small piece for cello, chronologically, is the “Sérénade” Op. 98. Dedicated to the Catalan cellist Pablo Casals, the piece was a gift to celebrate Casal’s engagement to the Portuguese cellist Guilhermina Suggia. Never mind that the relationship never transformed into marriage. Casals was enthused about the music as he wrote to the composer, “The Serenade! It is delightful every time I play it; it seems new, so beautiful, is it.” For a variety of obvious personal reasons, Casals neither performed the piece in public nor recorded it during his long career.

The “Sérénade” unfolds as an uneasy conversation between the two instruments. The cello line presents a delightful melody akin to the best of Fauré’s songs. However, the piano part is more than just mere accompaniment, interweaving melodic lines and unsettled harmonies. It immediately interrupts the lyrical seductiveness of the melody with arpeggio figuration before taking it over completely. Despite its brevity, the “Sérénade” is surprisingly complex, painfully avoiding rhythmic and harmonic resolutions.

Cello Sonata No. 2

Fauré has almost completely lost his hearing when he started work on his 2nd Cello Sonata, Op. 117. Actually, he was commissioned by the French government to write a funeral march for a military band for a ceremony to be held on 5 May 1921. That particular date marked the 100th anniversary of the death of Napoleon. The sombre theme he composed for the occasion remained in his mind and, as he said, “turned itself into a sonata.”

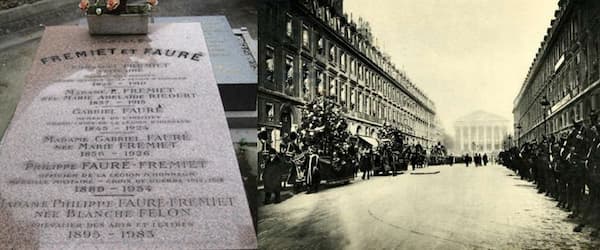

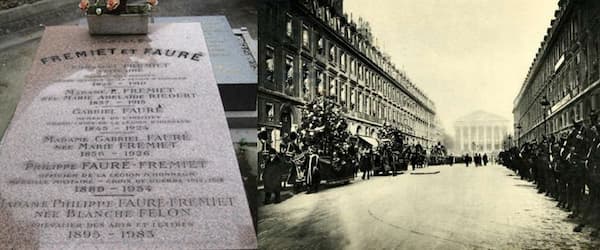

Gabriel Fauré’s grave and funeral

The reworked funeral march takes its place as the central “Andante” in the Sonata, exuding a relaxed tranquillity reminiscent of the mood presented in his Elegy, Op. 24. This sense of nostalgia is prefaced by an essentially lyrical opening movement that features two contrasting themes intertwined in free counterpoint. Jean-Michel Nectoux regarded the joyful finale “as one of the great Fauréan scherzos,” which sounds like an ode to life, “a moving profession of faith from an old man who knows that the end was approaching.”

Vincent d’Indy expressed his admiration for his friend’s work: “I want to tell you that I’m still under the spell of your beautiful Cello Sonata… The Andante is a masterpiece of sensitivity and expression, and I love the finale, so perky and delightful… How lucky you are to stay young like that!” Fauré continued to search for the purpose of music and wrote, “And what music really is, and what exactly I am trying to convey. What feeling? What ideas? How can I explain something that I myself cannot fathom?”

Fauré died from pneumonia on 4 November 1924 in Paris at the age of 79. His last words questioned, “Have my works received justice? Have they not been too much admired or sometimes too severely criticized? What if my music will live? But then, that is of little importance.” Fauré would certainly be delighted to know that his compositions for the cello are still performed with great enthusiasm and regularity. They beautifully reflect Fauré’s final thoughts that “music exists to elevate us above everyday existence.”