Richard Wagner (born May 22, 1813; February 13, 1883). No composer has had so deep an influence on the course of his art, before or since. Entrepreneur, philosopher, poet, conductor, one of the key composers in history and most remarkable men of the 19th century, Wagner knew he was a genius. He was also an unpleasant, egocentric and unscrupulous human being.

Richard Wagner’s mother, Johanna, was the daughter of a baker in Weissenfels (though some papers show that she may have been the illegitimate daughter of Prince Friedrich Ferdinand Constantin of Weimar). At the time of Wagner’s birth, she was married to a police registrar named Karl Friedrich Wagner, who died when Richard was only six months old. Johanna had already been having an affair with Ludwig Geyer and had a daughter, Cäcilie, six months after they were married in 1814.

Geyer proved to be a profound influence on the young Wagner and surrounded him with books and paintings and, of course, introduced him to the theatre and music. Geyer died when Wagner was only eight but the seeds had been sown. It was literature that was the initial attraction, though, not music. Wagner was only 11 when he wrote a drama, drawn from Shakespeare and the Greeks, in which 42 characters died in the first four acts, and some of whom reappeared as ghosts in the fifth act.

His latent passion for music was aroused by a performance of Weber’s Der Freischütz; when he heard Beethoven’s Fidelio for the first time at the Gewandhaus, Leipzig, music became an obsession. He made arrangements of Beethoven’s symphonies, began to absorb scores and produced his first compositions: two orchestral overtures. These were premiered in Leipzig in 1829, the first works of Wagner to be performed. And all this before he had had any formal training.

A rebellious spirit

His future character traits were beginning to emerge – a rebel who was expelled from the Thomasschule in Leipzig and who was more concerned with duelling, drinking, gambling and women than his law studies at the University of Leipzig. During his brief sojourn there (he never took his degree), he became well known as a compulsive talker and for his dogmatic views.

In 1831 he left to undertake six fruitful months of studying counterpoint with the cantor of the Thomasschule. His teacher, Theodor Weinlig, admitted that after that period there was nothing more he could teach him. As far as we know, this was the only professional instruction he ever received. He did not have any further music lessons. Then Wagner struck out on his own, writing a symphony and three operas – Die Hochzeit and Die Feen to his own bloodcurdling librettos, and Das Liebesverbot based on Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure.

Musical disaster and poverty

At 22, Wagner was the conductor of a small opera house in Magdeburg. One reason for taking the job – the theatre was on the verge of bankruptcy – was his pursuit of a pretty young actress named Minna Planer. He was pursued by creditors claiming their gambling debts but in March 1836 the opera house produced Das Liebesverbot. It was such a fiasco that the theatre was empty at the second performance. It bankrupted the opera house. Wagner, overwhelmed with financial demands, left with Minna for a similar conducting post in Königsberg. They married in November 1836. The two of them then went on to Riga in Russian Poland to another opera post where they stayed unhappily for two years.

Eventually, Wagner was dismissed, hounded by creditors, his passport confiscated and he was forced to flee Russia via a smugglers’ route. At length, the couple arrived in Paris. From 1839 to 1842, he and Minna lived in abject poverty (on two occasions he was imprisoned for debt).

Building a reputation

But then came his first taste of success. His opera Rienzi, which he had begun in 1837, was accepted for production at the Dresden Opera. The opera, written in the approved Meyerbeer style, was a complete triumph and made Wagner’s name known throughout Germany.

Dresden next offered a production of Der fliegende Holländer, Wagner’s first tentative steps towards a new style of opera. It resulted in complete failure but in February 1843 Wagner was made director of the Dresden Opera. In the following six years he raised the standard of performance there to unprecedented heights in a series of painstakingly produced performances, including, in October 1845, the premiere of his own Tannhäuser. By 1848 he had almost completed a third operatic masterpiece, Lohengrin.

The Ring

That year was the year of revolution in Europe and its spirit had spread to Saxony by 1849. Wagner sided with the revolutionaries, producing radical pamphlets, making political speeches and sympathising with the rioters. When the revolution came to nothing he was forced to flee Germany and for the next 13 years he lived in exile in Zurich. Here, he formulated his revolutionary ideas about opera and the ‘music of the future’: the concept of ‘music drama’ involving a synthesis of all the arts. The plan that began to occupy his mind was a giant project of four dramas in which all his theories would be realised, an opera cycle called Der Ring des Nibelungen. It took him a quarter of century to complete it.

Meanwhile, Franz Liszt had mounted the world premiere of Lohengrin (Weimar, 1850). Its fabulous success made Wagner the most famous living composer of German opera, though he was unable to attend any performances of his work there. At one time he lamented that he was just about the only German who had never seen a performance of Lohengrin.

Tristan und Isolde

While working on The Ring, Wagner interrupted his labours with two other music dramas, Tristan und Isolde (1859) and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1867). The friendship and generosity of a wealthy silk merchant, Otto Wesendonck, allowed him to live in a luxurious villa in Zürich while he was working on The Ring and Tristan. The friendship and generosity were repaid by Wagner having a passionate affair with Otto’s wife, Mathilde.

Much of Tristan was written under her influence; she may even have been the inspiration for the work, though it’s just as likely that Wagner fell in love her because he was working on Tristan. Whatever, Tristan und Isolde is one of the most important works of the 19th century and its harmonic innovations exercised an enormous influence on the future of music, paving the way for Mahler and Schoenberg.

At length, the domestic situation in Zurich became impossible. Otto was fully aware of the situation and eventually provided funds for Wagner and Minna to travel to Paris in 1859. Wagner’s marriage had broken down irretrievably and soon a third married woman had entered his life.

Cosima

In 1862 Wagner fell in love with Cosima, the daughter of Franz Liszt and the wife of his friend and champion, the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow. The mesmeric power Wagner exercised over his admirers is no better illustrated than by von Bülow. First, Wagner and Cosima had an illegitimate daughter named Isolde; they then had a second illegitimate daughter, Eva. Only then, and after Minna had conveniently died in 1866, did Cosima desert her husband and set up house with Wagner. Throughout, von Bülow remained devoted to Wagner and wrote to Cosima, ‘You have preferred to devote your life and the treasures of your mind to one who is my superior. Far from blaming you I approve your action from every point of view and admit you are perfectly right’.

Cosima was the woman for whom Wagner had been searching all his life, someone of great intelligence and independence of mind who would provide stability, adulation and understanding whenever it was needed. He remained with her for the rest of his life – well, nearly. After Wagner’s death, the imperious Cosima, born in 1837, became the guardian of the Wagner shrine and survived until as late as 1930.

Return to Germany

In the meantime, a political amnesty allowed Wagner to return to Germany in 1860. Four years later, his fortunes changed dramatically when the young King Ludwig II of Bavaria ascended the throne. He invited Wagner to Munich and promised him unlimited support for all his projects. It’s very likely he was in love with Wagner but, at any rate, a mutual admiration society flourished on a grand scale and, between 1865 and 1870, Munich was host to the world premieres of Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre (the last two being the first completed sections of The Ring).

Ludwig’s lavish support of Wagner soon brought him into conflict with the Bavarian Cabinet, who advised that the whole economy would collapse if the King continued his patronage on such a reckless scale. They were also frightened by Wagner’s political dabbling and his hold over the King, scandalised by his morals (everyone knew about his relationship with Cosima) and observed this arrogant musician with more than a little concern.

Wagner retreated to a palatial estate on Lake Lucerne (paid for by Ludwig) where he was joined by Cosima. Here Eva was born (1867), and their first son Siegfried (1869). They eventually married in August 1870.

The building of Bayreuth

In 1871 Wagner announced plans for another gargantuan scheme. Not a music drama but a building, a special festival theatre where his works could be mounted under ideal conditions, produced to his own specifications. The council of the little Bavarian town of Bayreuth offered him a site and in May 1872 the cornerstone was laid.

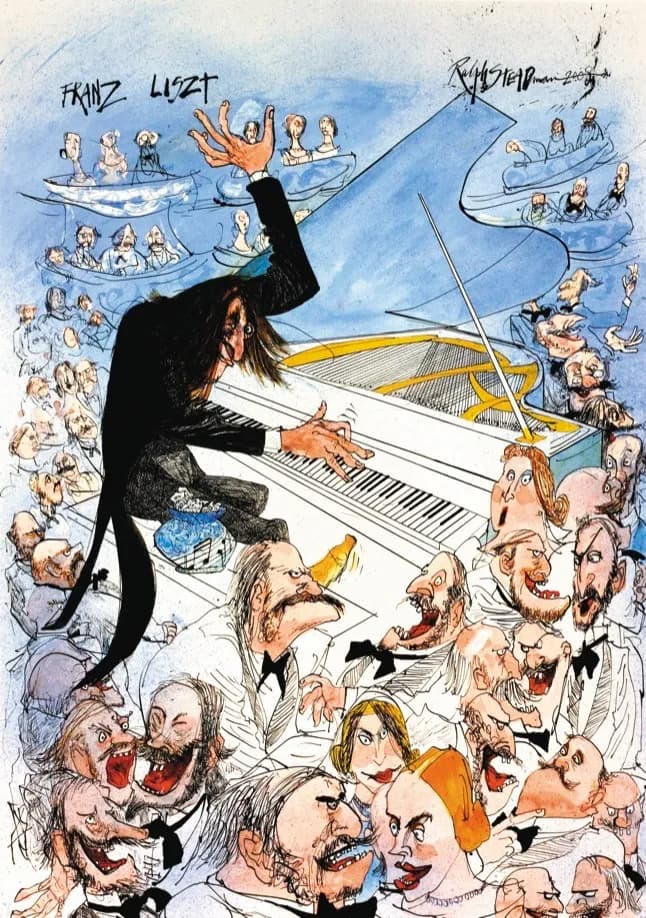

It was a huge undertaking and Wagner characteristically took to realising his dream with extraordinary vigour and determination. No setback troubled him – he persuaded wealthy patrons to provide part of the subsidy, he conducted concerts to help raise money, King Ludwig coughed up 100,000 talers and, eventually, the Bayreuth Festival Theatre was unveiled on August 13, 1876.

The opening performance was the first complete presentation of the Ring cycle, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung receiving their world premieres. The event attracted world attention. Four thousand visitors were crammed into Bayreuth, including the Emperor and Empress of Germany, the Emperor and Empress of Brazil and Grand Duke Vladimir of Russia, along with other crowned heads and many of the greatest composers, including Tchaikovsky, Gounod, Saint-Saëns, Grieg and Liszt.

Such novelties as gas lighting linked to electric projectors and a magic lantern illuminating the Ride of the Valkyries matched the startling originality of the operas themselves. The festival made a huge deficit but at the closing party Wagner had the good grace to pay tribute to Liszt. He owed him, he said, everything. Today the Bayreuth theatre remains a living shrine to Wagner’s music and vision.

Basking in his fame, relative wealth and security (though money worries continued to nag), living in the comfort of the Villa Wahnfried a few miles from the festival theatre in Bayreuth, Wagner settled down to other things. He had a final fling with a married woman. This time it was the beautiful daughter of the poet Théophile Gautier, Judith, wife of the poet Catulle Mendès. Judith Mendès, who was 40 years younger than Wagner, actually moved into the Villa Wahnfried (Cosima turned a blind eye) before returning to her husband in 1878.

Poisonous views

Wagner finished his last opera or ‘consecrational play’, Parsifal, while producing a series of pamphlets and publications. In his all-embracing wisdom, he promulgated his lofty views on any number of topics. He believed the world could be saved if everyone ate vegetables instead of meat; he ranted on about racial purity – the Jews were former cannibals, Christ was not a Jew but an Aryan, the Aryans had sprung from the gods, and so forth – all the things which led Hitler to say ‘Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner’.

Death

In August 1882 Wagner conducted a performance of Parsifal. It was his last public appearance as a conductor. He was exhausted and began to have premonitions of death. Later in the year he, Cosima and their children travelled to Venice for a lengthy holiday. As a birthday gift to his wife, Wagner conducted a private performance of his youthful symphony in December 1882. It was his last musical act. Six weeks later he died of a massive heart attack. His body was brought back to Bayreuth, where it was buried in a vault in the garden of his villa to the strains of the funeral march from Götterdämmerung.

Incidentally, King Ludwig was faithful to the end to his ‘divine friend’, the man to whom he wrote, ‘I can only adore you…an earthly being cannot requite a divine spirit’. His mental state deteriorated and he was committed to an asylum. On June 13, 1883, three months to the day after Wagner’s death, Ludwig overpowered a psychiatrist who was escorting him on a walk and dragged him to the bottom of the Starnberg Lake, drowning himself in the process.