Classical music audience

The argument for more ‘audience participation’ (and noise) at classical concerts usually goes something like this: in Mozart’s day, people enjoyed food, drink, and gossip during performances. Often the musicians, and the performance, were almost secondary to the noisy socialising and carousing. The advocates for “noise at concerts” hint that we need to return to an 18th-century mode of behaviour when experiencing classical music and that this approach will attract that elusive “younger audience” and make classical music “more accessible”.

The tradition of listening to concerts in silence, in a special building designed for that purpose, developed during the middle of the 19th century and soon became the “proper” way to experience live classical music (Wagner was one of the first to advocate silence at concerts.). Most people who go to classical concerts today not only accept that listening in silence is an established part of concert etiquette, it also makes the concert experience more enjoyable for everyone.

In addition to the ‘social code’ of the classical concert – knowing when to keep quiet for the benefit of other people, including the performers – there are good, practical reasons for listening to classical music quietly.

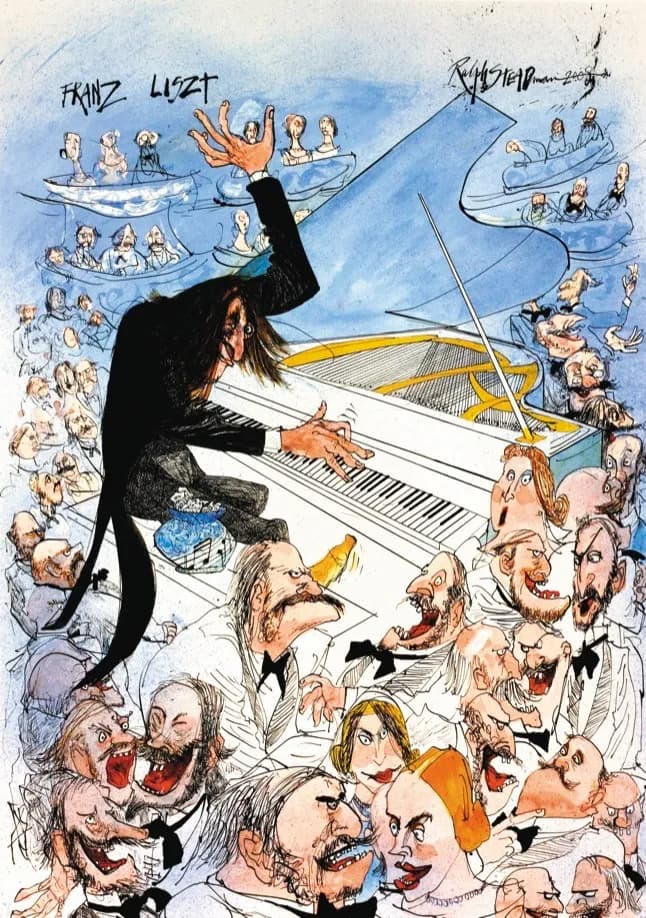

Liszt concert by Ralph Steadman

Silence in the concert hall is a sign of respect for the performers. Classical musicians invest significant time and effort into perfecting their craft, and the concert stage is where they share their artistry with the audience. By maintaining silence, attendees show appreciation for the dedication and talent of the musicians, acknowledging their hard work and skill.

Silence creates an environment that encourages deep musical engagement and allows the myriad nuances of the music to be fully appreciated. Why? Because classical music often contains intricate melodies, harmonies, and subtle dynamics that demand attentive listening. Silence in the concert hall allows listeners to immerse themselves in the music without distraction, allowing them to experience the emotional depth and expressive or artistic intentions of the music. Unlike some other forms of entertainment, classical music’s beauty often emerges from its delicate interplay of soft and loud passages, intricate phrasing, and nuanced interpretations. The silence maintains an atmosphere that helps capture these subtleties.

© Unsplash

For many of us, myself included, the chief attraction of classical music concerts, apart from the music itself, of course, is the opportunity to escape into quiet introversion for a few hours. I love going to concerts with friends, listening with others, but ultimately, it’s a very personal, often introspective experience. In today’s fast-paced, frenetic, noisy world, I love the opportunity to be completely silent for a few hours, almost as a kind of retreat.

And the sense of collective listening in silence with 500 or more other people can be very potent. We have all been at concerts where the power of the music and performer encourages a really intense form of listening on the part of the audience. I experienced it when hearing Igor Levit play Beethoven’s last three piano sonatas at London’s Wigmore Hall some years ago when the audience listened, utterly transfixed, in complete silence, only to make a seemingly collective exhale some long moments after the music had faded into the silence. This kind of intense listening and the sense that one has been on a shared emotional journey is really powerful – quite rare in concerts, but it makes performances really memorable.

As concert presenters and performers strive to attract new audiences, especially younger audiences, the tradition of silence in classical music concerts is constantly being questioned. For some, it can feel unduly restrictive, unfriendly, or exclusionary. For others, it smacks of elitism (never mind that theatre etiquette requests that audiences remain silent as well…..). Today there is plenty of room for classical music to be presented differently – family concerts, relaxed concerts, open-air concerts, concerts in disused car parks (something I’ve experienced as part of previous Proms seasons), and other non-standard venues (bars, cafés, galleries and other ‘salon’ style settings). And yet often at such events, there is still a sense of ‘listening in silence’, or at least listening attentively on the part of the audience.

While there is room for evolving concert etiquette, the tradition of silence continues to be an integral aspect of classical music concerts, allowing audiences to deeply connect with the artistry and emotions conveyed through the music.

So, let’s let classical audiences remain silent. We show our appreciation in other ways – by applauding, cheering and bravo-ing at the end of the performance, and while these behaviours may seem antiquated, or even elitist (they’re not!) to some, to the regular concert-goer this is what comes out of silence.

Just like the music.

No comments:

Post a Comment