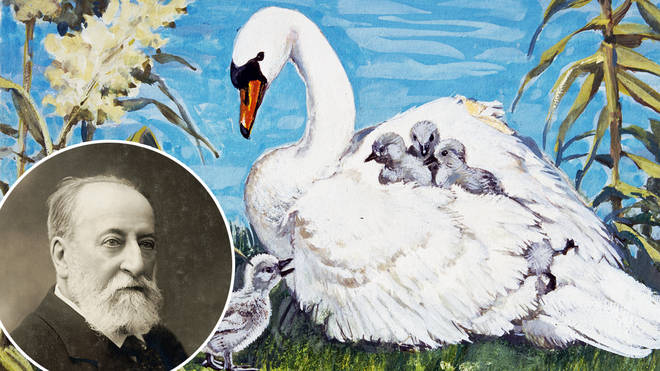

Lions, swans, donkeys and… pianists? Here are all 14 movements of The Carnival of the Animals, and what they’re about.

The French composer Camille Saint-Saëns took himself quite seriously. So seriously, in fact, that he banned one of his best-known pieces from being performed in public until after he had died, in case it damaged his reputation as a composer of “serious” music.

Thankfully, the wishes set out in his will were granted, and The Carnival of the Animals was published in 1922, a year after his death, and received its public world premiere on 25 February that year.

The Carnival of the Animals is a comedic musical suite, comprised of four short movements, that was written for a bit of light relief after the composer returned from a fairly disastrous concert tour.

Originally written in 1886, the piece is now one of the works Saint-Saëns is best remembered for, and has provided a staple for the cello repertoire as well as inspiration for John Williams’ score to the Harry Potter film franchise.

Here are each of the 14 movements in order, their titles, and what they’re all about.

Introduction and Royal March of the Lion

A bold and stately introduction, fit for the king of the jungle. Piano tremolos with dark and brooding strings open the introduction before a dramatic piano glissando heralds the arrival of the roaring ruler.

Enter: the lion. A regal major chord fanfare rings out from the two pianos, before union strings play out the big cat’s theme, ornamented by marching piano triplets and high trills.

Hens and Roosters

Persistent pecking is immediately brought to mind when the piano and violins begin their incessant staccato quavers, interrupted by irregular chirrups.

The two pianos pass between them a parody of the rooster’s ‘cock-a-doodle-doo’, and stretched out scratchy string glissandos mimic the cooing and braying of the hens.

Wild Donkeys (Swift Animals)

Saint-Saëns portrays the skittishness of wild donkeys with a hurricane of racing semiquavers, played in octaves by two pianos.

The flighty creatures are gone almost as quickly as they arrived, as the whole movement only lasts around 30 seconds.

Tortoises

Ah, to be a slow-moving tortoise lazing around in the afternoon sun. Saint-Saëns was really having a laugh when he wrote this one.

Over pulsing piano chords, in a triplet rhythm, a string quartet plus plays an agonisingly slow rendition of Jacques Offenbach’s Can-Can from his opera Orpheus in the Underworld. Well played, Camille, well played.

The Elephant

Saint-Saëns clearly felt as if he hadn’t ridiculed the animal kingdom enough, as his scornful gaze next fell on the poor elephant.

In a duet between the double bass and the piano, the Carnival’s elephant is cruelly taunted into dancing by a heavily satirical waltz. Famously not known for being light on their toes, Saint-Saëns characterises the elephant in a juxtaposition of light piano notes and staccato melodies with the deep, weighty tones of the double bass.

There are more thinly veiled musical jokes here too, as Saint-Saëns quotes melodies from Felix Mendelssohn’s sprightly ‘Scherzo’ from A Midsummer Night’s Dream as well as ‘Dance of the Sylphs’ from Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, both originally written for high-pitched instruments with light tones.

Kangaroos

The kangaroo isn’t often represented in Western classical music, and it’s hard to imagine any composer capturing their bounding energy quite as well as Saint-Saëns did.

Two pianos pass between them two melodies: a sprightly staccato scale, complete with grace notes, that gets louder and faster as it rises and softer and slower as it falls.

Aquarium

From the Australian desert to the depths of the ocean, Saint-Saens’ Aquarium effortlessly captures the beauty and wonder of the underwater world.

The twinkling high notes of the piano and glass harmonica, the pure and open tone of the flute, and the shimmery mystical sound of muted strings all come together to wash over the listener in a stream of swirling notes.

Characters with Long Ears

Enough with this serious music malarkey, thought Saint-Saëns, and after that brief but beautiful watery interlude, he returned to his musical jokes. Although the title is a little cryptic, many believe it to be a taunt at music critics, comparing them to braying donkeys.

A duet between two violins, they alternate between high notes at the very top of the instrument’s range and sliding notes towards the bottom of the register, mimicking the animal’s signature “hee-haw”.

The Cuckoo in the Depths of the Woods

Two pianos play steady, soft quaver chords, replicating the calm, vast expanse of the forest.

A single offstage interjects occasionally with a two-note calling card, mimicking the cry of the cuckoo.

Aviary

Quietly buzzing tremolos on violins and set the scene for this movement, a flurry of airborne activity as the flute takes to the skies in a whirlwind of notes.

With a melody that spans nearly the entire range of the instrument, the swoops and dives in relentless runs of demi-semi-quavers as two pianos join the chorus of the skies with intermittent chirrups and trills.

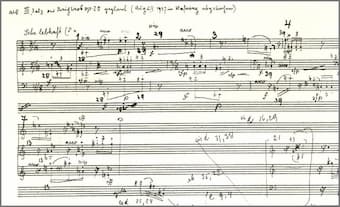

Pianists

Saint-Saëns wasn’t satisfied with only poking fun at the animal kingdom and takes a jibe at pianists. Ooh, burn.

This must have been more than a little tongue-in-cheek, as Saint-Saëns was a pianist himself. This movement is just like listening to simple piano finger exercises, and on the original score, the editor even specified that the two performers “should imitate the hesitant style and awkwardness of a beginner”. In some performances, the pianists even deliberately move out of sync with one another.

Fossils

As all good things come to an end, so do animals become fossils. In iconic narration of The Carnival of the Animals recorded with the New York Philharmonic he pointed out the joke, which is that all the pieces quoted in this movement were the ‘fossils’ of Saint-Saëns’ time.

Beginning with a bit of self-deprecation, the movement opens with a bone-rattling xylophone melody that quotes Saint-Saëns’ own work, Danse Macabre, written just over 10 years earlier, before moving on to poke fun at French nursery rhymes, including Twinkle Twinkle Little Star and ‘Au clair de la lune’, as well as an extract from Rossini’s opera The Barber of Seville. The click-clack of the xylophone is also joined by a clarinet, two pianos, a string quartet and double bass.

The Swan

Perhaps the most famous of the 14 movements and certainly the most graceful, Saint-Saëns couldn’t stay away from writing beautiful melodies for too long.

Two pianos evoke the rippling flow of a body of water, over which glides the soaring and elegant swan. Even Saint-Saëns himself could recognise the brilliance of this work, and it was the only part of The Carnival of the Animals that he permitted to be published during his lifetime.

Finale

Saint-Saëns’ dazzling finale sees all 11 performers come together for the first time in the entire piece. It opens with the same piano trills as in the introduction and is soon fleshed out by the piccolo, clarinet, glass harmonica and xylophone.

The movement cycles quickly through the animals that have appeared before with spirited interjections from the lions, hens and kangaroos, before the donkey has the last laugh with six “hee-haws” that bring the piece to a close.