It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Popular Posts

-

Witness the "𝗛𝗮𝗿𝗺𝗼𝗻𝗶𝗲𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗛𝗲𝗿𝗶𝘁𝗮𝗴𝗲: 𝗔 𝗦𝘆𝗺𝗽𝗵𝗼𝗻𝘆 𝗼𝗳 𝗣𝗵𝗶𝗹𝗶𝗽𝗽𝗶𝗻𝗲 𝗖𝗼𝗹𝗼𝗻𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗶𝗰...

-

182,711 views Feb 22, 2025 #WendyKokkelkoren #Goosebumps #Ballads 00:00 - 05:00 Hallelujah 05:01 - 09:38 I Will Always Love You 09...

-

André Rieu's Son Says Goodbye After His Father's Tragic Diagnosis In this heartfelt and emotional video, we explore the touching mom...

-

by Janet Horvath , Interlude Fans of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart will likely be aware that he was taught, shaped, and influenced by his fath...

-

Born in Sonzowka-Jekaterinoslaw/Russia on April 23, 1891, Serge Prokofieff passed away on March 5, 1953. His father was an estate trustee...

-

New music of such variety, imagination and originality, there is something here for everyone Caroline Shaw What were you doing when you were...

-

By Georg Predota, Interlude In the 1840s, the Parisian instrument builder Adolphe Sax provided a welcome addition to the family of woodw...

-

by Georg Predota, Interlude “Inspiration is an awakening” Giacomo Puccini One of the most important and influential composers in the histor...

-

International performer Michael Bublé together with the Megastar deliver a breathtaking rendition of Frank Sinatra’s timeless pop song ‘The ...

-

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (his complete name was Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus; Theophilus became Amadeus later) was born o...

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

How Beethoven Revolutionized the Symphony

Thursday, February 16, 2023

Thursday, October 27, 2022

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 "Emperor" Op. 73 - Daniele & Maurizio Po...

Friday, October 7, 2022

Johannes Brahms and His Family

by Hermione Lai , Interlude

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms would not do well on Facebook, Twitter, or TikTok, that’s for sure. Of course, he is one of the most widely performed and beloved composers of all time. In the historiography of music, he stands alongside Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven as one of the shining testaments to human inspiration and creativity. I have always had a love-hate relationship with the music of Brahms. On one hand, his music seems very tightly constructed, almost like a textbook on counterpoint and harmony. But that’s only part of the equation, as “the lush and organically grown surface of the music” is full of emotional intensity. So what do I hate about his music? Well, Brahms doesn’t seem to want to communicate what those feelings are all about. It’s almost impossible to get a sense of what he is trying to express or what inspired him. Being intensely private, his biography is probably not written into his music, and he always gives his compositions very bland and generic titles. Since there seems to be no direct way of accessing his private thoughts and emotions, maybe we can get a glimpse of his personality by looking at his relationship with his family?

The Mother: Christiane Brahms

Christiane Brahms

Johanna Henrike Christiane Nissen came from a line of town-councilors, pastors and teacher, and her mother’s side could be traced back in the fourteenth century. Her father had been a tailor, and Christiane later wrote, “I was sent out to earn money as a seamstress when only 13, and often continued to sew at home until midnight.” At the age of 19 she was employed as a maid in a private household for 10 years, and subsequently resumed her work as a seamstress, working for a Hamburg firm for eight years. When her sister married the longshoreman Johann Detmering in 1827, Christiane moved in with them and helped to sell sewing good at a little shop called “Nissen Sisters-Dutch Wares.” Christiane is described as “small, sickly, gimpy from a short leg, plain of face with enchanting blue eyes.” Apparently, she was also a complainer but “modest and kind-hearted and by no means an unintelligent woman with an interest in literature.” To earn extra money, the Detmering household also took in lodgers, and in 1829 a handsome young musician by the name Johann Jakob Brahms took up residence. He is described “as a poor but fine-looking figure of a man, with a handsome forthright face and flowing brown hair; and his dark gray eyes were roguish and merry.”

The Father: Johann Jakob Brahms

Johann Jakob Brahms

Johann Jakob Brahms hailed from Holstein, and showing great musical aptitude decided on a career in music at an early age. His father refused to allow his son to study an instrument, and thus he secretly took music lessons and started playing with local musicians. When his musical secret was discovered, Johann Jakob ran away from home. Undeterred he learned to play several instruments, including the violin, viola, cello, flute, and flugelhorn and made his way to Hamburg in 1826. Initially, he made a squalid living by playing as a street musician, and occasionally with little bands in drinking establishments. Johann Jakob soon concentrated his efforts on the double bass, and for many years he would perform in a sextet at the popular Alster Pavilion, as well as in the orchestras of the Stadtheater and the Philharmonic Society. Granted Hamburg citizenship in 1830, he swore to “honor and decently represent the city,” and since he was now a wage-earning citizen, he started to look for a bride. One week after he had moved into Ulrikusstrasse and having laid eyes on Christiane, he declared his wish to marry her. “The precipitous proposal surprised the prospective bride, not least because, at 41, she was 17 years older than her suitor.” I think Christiane received a good talking to from her brother-in-law, who told her to accept the proposal; after all, it was her last chance of a home, children, and happiness.

The Marriage

Birthplace of Brahms: No. 24 Specksgang, later renumbered to No. 60 Speckstraße, Hamburg

In a letter to her son Johannes shortly before her death, Christiane wrote, “And so, I considered it Destiny.” Christiane and Johann Jakob were married on 9 June 1830. Their first years appeared to have been reasonably happy, although they initially lived in extremely humble circumstances. Contrary to statements by the Brahms biographer Max Kalbeck, “Johann Jakob’s earnings, though modest, placed him and his family well above the poverty line. Far from being indicative of impoverished circumstances, the frequency with which he changed accommodations, no fewer than eight or possibly even nine times between 1830 and 1864 was, in fact usually prompted by a desire for larger and more expensive apartments.” In 1833, the family moved to a “ramshackle half-timbered house on Specksgang—Bacon Lane—in the Gängeviertel.” That district was well known for its sailor’s dancehalls that doubled as brothels. The family probably lived on the first floor in two very small and low-ceilinged rooms. One room was probably a combined kitchen and entrance, and the other a sitting room with a sleeping closet. There was no bathroom or running water, with people drinking unfiltered water from the canals. When a sanitation inspector entered the area as late as 1892, he wrote, “I have never seen such unhealthy places, pest-houses, and breeding-places for every infection… I forget that I am in Europe.” It was from that location that on 7 May 1833, a proud father announced the birth of a healthy son, which he named Johannes.

The Sister: Elise Brahms

Although Christiane was already in her early 40s, the marriage bore three children with Elisabeth (Elise) Wilhelmine Louise born on 11 February 1831. The child was afflicted with chronic migraine headaches that could keep her in bed for weeks. She is described as “looking a good deal like her brother but without the aura, the penetrating intelligence in the eyes, or the sheer attractiveness.” Because of her sickly constitution, she seemed to have been content to play her role as a “semi-invalid and patient virgin” and essentially helped with various housekeeping tasks. “She adored flowers and birds, shiny floors and tidiness, and entertaining friends.” Her mother affectionately called her “the fat dumb peasant.” Elise had no musical talent but was highly interested in Johannes’ activity and she took great pride in his growing reputation. “Her deep affection is reflected in her numerous letters to him, more than 200 of which have survived.” In turn, Brahms always spoke and wrote affectionately to his sister and took on a protective and counseling role. This was certainly the case when Elise, at the age of 40, was looking to marry Johann Georg Grund, a clockmaker, and widower with six children. Johannes tried to dissuade his sister and even offered to buy her a place in a residence for unmarried or widowed women. Elise, however, had made up her mind and Johannes continued to provide financial help to his sister during her marriage.

The Brother: Fritz Brahms

Johannes Brahms at age 20

Fritz Brahms, born on 26 March 1835 was known around town as “the wrong Brahms.” This already gives us some idea about the relationship between the Brahms brothers. To be sure, Fritz was reasonably bright and talented, but he “had the difficult task psychologically to live in the shadow of the golden child.” Initially, his father wanted to turn Fritz into an orchestral player but the boy resisted. Although he studied violin with the Concertmaster of the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra, he eventually gave up playing that instrument and sold his violin in 1856. Instead, and following his brother, he took up the piano and studied with Otto Cossel and Eduard Marxsen. However, he seems to have soon realized that he was not really equipped for a career as a professional pianist. Clara Schumann heard him perform and wrote, “On the whole, though, he possesses quite a good technique, only I find his playing so very dull.” Fritz eventually established himself as a respected music teacher in Hamburg, and for a time, he was also active as a piano teacher in Caracas, Venezuela. The two brothers never really got into big drawn-out fights, as most of the time, Johannes simply ignored Fritz. As time went on, the relationship became more strained, and Johannes wrote to his father in 1871, “I am not staying with you on my forthcoming visit to Hamburg because of Fritz. I have told Fritz how I feel. If he has nothing to say to me, nothing by way of explanation, I really don’t see why I should see him.” However, during the last 10 years of Fritz’s life, in which he experienced increasingly ill health, Johannes repeatedly provided him with financial assistance.

The Estrangement

Brahms: A German Requiem

The considerable differences in temperament and ages of Johannes’ parents had little consequence at first, but became increasingly burdensome as time went on. When Johann Jakob was still a robust man in his early 50s, Christiane had become an old woman. She was described as “having faded into a little old withered mother who busied herself unobtrusively with her own affairs, and was not known outside her dwelling.” In the weeks before her death, Christiane wrote a long letter to Johannes, “so that I can die in peace, knowing that my child has no false ideas about me.” She accuses her husband of meanness toward her and her children, and of having made her life unnecessarily hard throughout their marriage.” Specifically, she accused her husband of having lost a good deal of the family savings by playing the lottery, and by making expensive purchases for his own comfort and pleasure.

There had always been a strong bond between mother and son, as she wrote, “I never forget you when I pray in the evening, and when I get up in the morning, my first thought is of you.” And Johannes wrote to Clara, “How marvelous it is to be staying with my parents! I wish I could take my mother everywhere with me.” And when he saw her after her death he said, “She was quite unchanged and looked as sweet and gentle as in life.” Brahms was greatly saddened by the mutual resentment experienced by his parents, and he initially sought to bring about reconciliation. Ultimately, he accepted the separation and he did not take sides in the dispute. As he wrote to his father, “Believe me that no son can love his father more deeply than I do and that no one can feel the sadness of our position more keenly and sincerely than, unhappily, I now do.” Brahms even rented and paid for an apartment and his sister, with a separate room for his father. Sadly, Christiane suffered a stroke and died in 1865. Brahms later denied that his Requiem was inspired by his mother’s death, but he must certainly have had her in mind when he wrote the fifth movement to the text, “I will comfort you, as a mother comforts her child.”

The Stepmother: Karoline Louise Brahms

One year after his mother’s death, his father married Karoline Schnack. She also hailed from Holstein, and had been married and widowed three times. Karoline was 18 years younger than Johann Jakob, and Johannes felt no resentment towards his stepmother but seemed to have been happy for his father. As he wrote to him, “Give my regards to the future mother and tell her, she could not have a more grateful son than me, if she makes you happy.” By all accounts, Karoline was an extremely kind-hearted, cheerful, and capable woman, “experienced in running a household efficiently.” All too soon, however, Brahms got news of his father’s grave illness. Johann Jakob had been ailing for the better part of a year and was forced to resign his post at the Philharmonic. Although Johann Jakob did not complain of any particular symptoms, a physician diagnosed cancer of the liver. Johannes apparently spent “the next fortnight at the bedside of the stricken man, whom he watched with tender care and tried to cheer with loving encouragement.” Johan Jakob died on 11 February 1872 in the presence of his wife and two sons.

Grave of Caroline Brahms

Brahms wrote to Karoline shortly after his father’s death, “I can’t attempt to try to console you. I know all too well what we have lost and how lonely your life has become. But I hope that you are profoundly and doubly conscious of the love which others have for you, the love of your son Friedrich, of your admirable sister and her children, and lastly my own love which belongs to you fully and entirely.” Brahms provided lodgings for his stepbrother Friedrich and his mother in the country town of Pinneberg, and Friedrich continued to carry on his clock-making business. “He established himself in a pleasant shop, providing him with all the requisites for a new start, and wished to guarantee a comfortable home for Frau Karoline.” However, Karoline did not enjoy country life and returned to Hamburg to run her own lodging business. Brahms repeatedly sent her money, and he did visit his stepmother whenever he was in Hamburg. In fact, in his will, he left her a life annuity of 5,000 marks.

Conclusion

To many commentators, “Brahms’ psychological depths remain a mystery.” As we have seen in his dealings with his family and friends, Brahms could be fantastically loyal and generous, but also unpleasant, secretive, occasionally mean-spirited, and full of irony and reserve. If his personality seems contradictory and conflicted, he found his balance in his compositions. As a scholar writes, he “deftly couched his romantic, melodious, emotional music in the classical form, creating a protective boundary that contained the emotionalism of his compositions in an articulated form and structure.” Brahms was socially awkward yet he could emphasize with poor, and hard-working people, and he loved children. I think that contentment and romanticized perfection, aspects that eluded him in his personal life, found a clear and sublime outlet in his music. It’s probably much more complicated than that, but to my mind, it does explain a lot.

Friday, August 26, 2022

Pianists and Their Composers

Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas – Scaling the Pianistic Everest

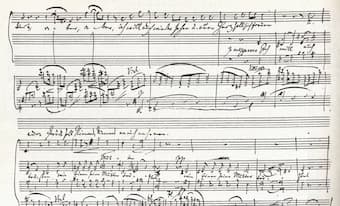

Manuscript of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 110

Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas are often referred to as the ‘New Testament’ of the pianist’s repertoire, and for many pianists they offer a remarkable, quasi-religious journey – physical, metaphorical and spiritual – through Beethoven’s creative life. This is truly “great” music, that which is endlessly fascinating and challenging, intriguing and enriching, and such is the popularity of this repertoire that you can guarantee that somewhere in the world right now there is a concert featuring these remarkable sonatas.

“There is something about the personality of Beethoven that is so overwhelming, and I think that the sonatas are the pieces that go the deepest, that show him at his most exploratory, his most inventive, and at his most spiritual.” –Jonathan Biss

Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel listening to a playback at a recording session

The first pianist to record the complete Beethoven piano sonatas in the 1930s, just a few years after electrical recording was invented, Schnabel set the standard by which all subsequent recordings was set, and his playing is acclaimed for its intelligence and insight, emotional depth and spiritual understanding of this music. So fine were his recordings that one critic described him as ‘the man who invented Beethoven’.

Daniel Barenboim

Daniel Barenboim © Peter Adamik

“I’ve known these works for many years….but whenever I go back to this music I find something new.”

Beethoven’s piano sonatas have followed Daniel Barenboim throughout his career, and such is his affection for this music he has recorded the complete piano sonatas five times, most recently during lockdown when, during this period of enforced isolation, he decided to approach the sonatas anew. His first recording was made in 1950s when he was a young man. It is perhaps an indication of the reverence with which this music is held, and its distinctive challenges, that Barenboim has made so many recordings of the sonatas. For him, this is music which has an infinite appeal, to be taken up by other pianists who follow him.

Annie Fischer

Annie Fischer

It is interesting to note that few women pianists have recorded the complete Beethoven piano sonatas, Annie Fischer being an exception. The music of Beethoven was central to Fischer’s career and her recordings are still much admired, nearly 30 years after her death. Her style is unaffected and self-effacing, letting the music, and composer, speak, and her playing displays great nobility, elegance and humanity. Her recording of the complete piano sonatas is regarded as her greatest legacy.

Igor Levit

Igor Levit

“Beethoven’s music kind of creates this link between the player, the music, the audience. This triangle is enormously intense.” –Igor Levit in an interview with Jon Wertheim

Igor Levit released his first recording of Beethoven piano sonatas when he was just 26, an album which received huge acclaim for its intense expressivity and Levit’s mature approach balanced with a youthful ardour. He released his recording of the complete Beethoven sonatas in 2019.

In his performances of Beethoven, Levit produces a clear, lively and well-balanced sound, but he’s not afraid to roughen the edges of the music to create a more visceral impact. His concerts can be intense, almost uncompromising, but his Beethoven playing is some of the most exhilarating and adventurous to be enjoyed today.

Jonathan Biss

Jonathan Biss

For American pianist Jonathan Biss, Beethoven has been a close companion throughout most of his life, and during the past 10 years he has fully immersed himself in Beethoven: he has recorded the complete piano sonatas, performed complete cycles around the world, and also teaches an in-depth online course about the sonatas which has attracted over 150,000 students globally.

“As individual works, each is endlessly compelling on its own merits; as a cycle, it moves from transcendence to transcendence, the basic concerns always the same, but the language impossibly varied”

Biss is a “thinking pianist”, with an acute intellectual curiosity and an ability to articulate the exigencies of learning, maintaining and performing this music. His Beethoven playing has long-spun melodic lines, well-balanced harmonies, taut, driving rhythms, rumbling tremolandos, dramatic fermatas, carefully-considered voicing, subito dynamic swerves, and colourful orchestration. It is not to everyone’s taste, but his performances can be vivid, edge-of-the-seat experiences which reveal how Beethoven took the genre to the furthest reaches of what was possible, compositionally and emotionally.

Friday, August 5, 2022

Wednesday, July 13, 2022

Forgotten records: How Beethoven Lost a Symphony

Witt’s Jéna Symphony

by Maureen Buja

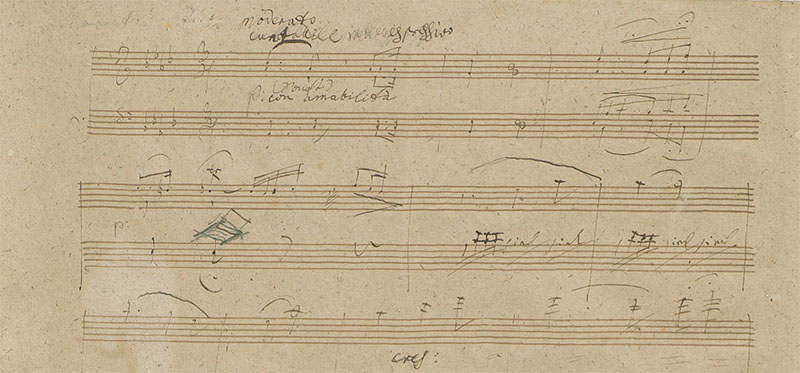

Friedrich Witt

In 1909, in the papers of the Academic Concert of the University of Jena, the music director found complete parts for a Symphony in C. Written on the 2nd violin part was ‘par Louis van Beethoven’ and, on the cello part, ‘Symphonie von Beethoven.’ This followed what Beethoven himself had written – that he had once attempted a Symphony in C major modelled on Haydn’s Symphony No. 97 before he wrote what we now know as his Symphony No. 1. This work fit that description perfectly.

The work was published under Beethoven’s name by Breitkopf und Härtel in 1911. It wasn’t until the discovery of another copy of the work by the scholar H.C. Robbins Landon that the situation became clear. The work that Robbins Landon discovered in Göttweig Abey was clearly signed by Friedrich Witt and he used that to convince the world that Witt was the composer, and not Beethoven. A second copy of the work found at Rudolstadt, also signed Witt, helped confirm the identification.

Walter Goehr (photo by Julia Crockatt)

Friedrich Witt (1770-1836) was a composer who was born the same year as Beethoven and had his own career as a composer and a cellist. From 1789 to about 1796 he was in the orchestra of the Prince of Oettingen-Wallerstein. While Witt was at the court, Haydn sent copies of his Symphonies Nos. 93, 96, 97, and 98 to Wallerstein, thus giving Witt material for the Jena Symphony. After he wrote his oratorio Der leidende Heiland, the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg appointed him as Kapellmeister in 1802. From 1814, when the court chapel was dissolved, to 1836 he was Kapellmeister at the Würzburg theatre and wrote operas for them, of which few survive.

The Jena Symphony probably dates from sometime between 1792-93 when Haydn’s symphonies arrived at Wallerstein and 1796.

When you listen to the work with Beethoven’s name attached, you immediately hear in the opening the characteristic rhythmic emphasis that Beethoven had in so many of his works. However, as the work continues, we aren’t so convinced. The work has been described as ‘a splendid example of symphonic writing from a time when this form was achieving both prestige and popularity with a growing music-loving public.’ We really have a work that reflects the state of the symphony after the death of Haydn and before Beethoven’s innovations in his Eroica symphony.

Friedrich Witt: Symphony in C major, “Jéna” – I. Adagio – Allegro Vivace

This recording was made in 1952 with The Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra led by Walter Goehr. Walter Goehr (1903-1960) studied with Arnold Schoenberg in Berlin and became a conductor before being forced to leave Germany in 1937, becoming music director for the Gramophone Company (later EMI). He was a busy conductor for EMI and, after the war, for other European recording companies. He also taught conducting, was a music arranger, conducted for the BBC, and was a composer in his own right, including writing film scores.

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

The Sound of Summer Rain in Classical Music Vivaldi, Rameau, Beethoven, Grofé and Whitacre

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Channeling the sound and fury of nature through an orchestra gives everyone, from the composer to the conductor to the orchestra (primarily the string section) a thorough workout.

Antonio Vivaldi: The Four Seasons – Violin Concerto in G Minor, Op. 8 (Summer)

© unripecontent.com

One of the most familiar of storms is in the third movement of Vivaldi’s Summer concerto from the Four Seasons (1720).

The sonnet that goes with the concertos sets this up at the end of the first verse: ‘Soft breezes stir the air, but threatening | the North Wind sweeps them suddenly aside. |The shepherd trembles, | fearing violent storms and his fate’. And then, in the 3rd verse: ‘The Heavens thunder and roar and with hail | Cut the head off the wheat and damages the grain’. And starting with rain in the violins, the heavens open.

Jean-Philippe Rameau: Platée – Act I Scene 6 – Orage

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt as Platée, 2000 (City Opera)

In Rameau’s 1745 opera Platée, two storms set the beginning and end of Act I. In an attempt to cure Jupiter’s wife of her jealousy, Mercury comes and tells the king of Greece that the opening storm has been caused by Juno’s jealousy. The King proposes a false love affair between Jupiter and Platée, a marsh nymph of outstanding ugliness.

Every time Juno is angered, another storm breaks out and the one at the end of Act I is a magnificent work of lightning flashes and drowning rain.

Rameau wrote the work for the wedding celebrations of Louis, Dauphin of France, son of King Louis XV of France, to the Infanta Maria Theresa of Spain. Despite having an opera based on marital infidelity and deceiving one’s spouse, the opera was popular and resulted in Rameau’s appointment shortly after the celebration to the position of Composer of the King’s Chamber Music.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, “Pastoral” – IV. Thunderstorm: Allegro

© behance.net

For his fourth movement Thunderstorm in his Pastoral Symphony, Beethoven used an orchestra that could do thunder (cellos and double basses), rain (violins), more thunder (timpani), lightning strikes (piccolo), and all of the other accompanying sounds and actions of a really good storm. At the end, the storm passes, with occasional grumbles of thunder in the distance.

Ferde Grofé: Grand Canyon Suite – V. Cloudburst

Ferde Grofé’s 1931 work The Grand Canyon Suite, gives us the sound and fury of a storm in the American West. The previous movement was Sunset and so this movements continues the stillness until suddenly, there are flashes of lightning, down bursts of rain in the piano, thunder in the timpani, and suddenly, we’re in the middle of a full-blown storm. But, as the title says, it’s a cloudburst so just a quick 3-minute flash storm, and then the sunset returns, fighting its way through the clouds.

Eric Whitacre: Cloudburst

Although we’ve seen how orchestras create rainstorms, one of the most innovative of modern composers, Eric Whitacre, has given us a magnificent choral storm in his 1991 work Cloudburst. The song text by Octavio Paz is El cántaro roto (The Broken Water-Jar) and is a reflection on water and no water, dust and the burnt earth, until the rain awakens. The chorus is augmented by two thunder sheets and a bass drum, but it is the chorus itself, through finger snaps and hand claps, that brings the storm to us and then it recedes.

Cloudbursts, slashing rain, echoing thunder, and bright flashes are these rainstorms. Use it to cool off from the summer heat, or to water the thirsty plants. It can be a welcome relief or an overwhelming flood, but no matter where it comes, it’s necessary to all life.

Friday, May 6, 2022

On This Day 7 May: Beethoven’s 9th Symphony Was Premiered

by Georg Predota

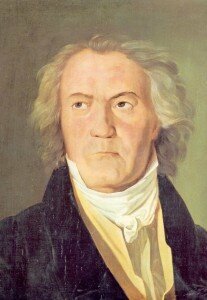

Beethoven in 1823 by Waldmuller

During the final stages of putting the finishing touches on his 9th symphony (which was also Beethoven’s last symphony), Beethoven was adamant that it should be premiered in Berlin. For years, Beethoven had lamented the changing musical taste of Viennese audiences, who numerously flocked to see the operatic entertainments offered by Rossini and other Italian composers. Beethoven and Rossini did meet once in Vienna in 1822, and supposedly Beethoven counseled his young colleague with the words, “Above all, make a lot of Barbers!”

For Beethoven, Rossini was a composer of light comedies, who embraced the “rankest lap of luxury” by pandering to populist demands. And supposedly, Beethoven quipped “Rossini would have been a great composer if his teacher had spanked him enough on the backside.” Whether this meeting actually took place or not is clearly beside the point, as it quickly became, and still is, part of a much larger narrative.

Caroline Unger

Beethoven’s threat to take his 9th symphony to Berlin was real enough, and it took a petition signed by a number of prominent Viennese patrons, friends, financiers and performers for the composer to change his mind. As such, Beethoven assembled a large orchestra and recruited Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger to sing the soprano and the contralto parts, respectively.

According to participating musicians, the work had only two full rehearsals before it was premiered on 7 May 1824 in the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna. Various stories and anecdotes surround this momentous occasion, but Beethoven—who had been profoundly deaf for almost a decade—took part in the performance by giving the tempos for each part and turning the pages of his score “as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.”

Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna

However, the “official conductor” Michael Umlauf, had instructed the singers and musician to ignore all of Beethoven’s instructions. When the work had ended, Beethoven was apparently still conducting and Caroline Unger is credited with turning Beethoven to face the applauding audience. Beethoven’s underlying conception of music as a mode of self-expression still resonates strongly today. Whether one agrees with, or rejects his compositional approach, after the premiere of Beethoven’s last symphony, a symphony combining a large orchestra, choir and vocal soloists for the first time, nothing in music could ever be the same.

Thursday, April 28, 2022

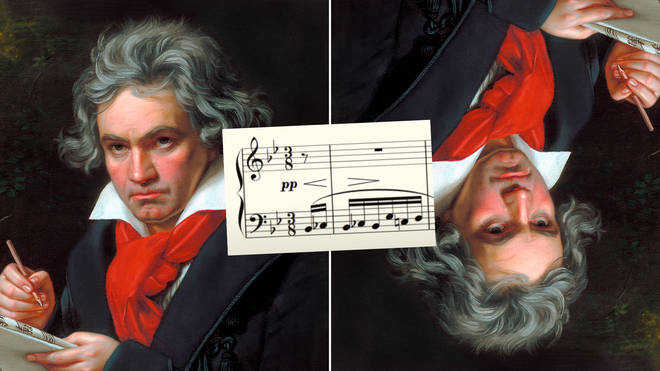

Beethoven’s Für Elise sounds surprisingly enchanting when ‘twisted’ upside down

By Sophia Alexandra Hall

@sophiassocialsWritten 212 years ago by Ludwig van Beethoven, ‘Für Elise’ gets a whole new makeover when you flip the piece upside down...

For April Fools Day 2021, the online community of score video makers were challenged with creating “twisted versions” of Beethoven’s solo piano work, Für Elise.

Videos ranged from turning the piece from a 3/8 time signature to 4/4, to nonsensical scores which placed each hand of the performer in different keys.

However, for Italian composer and video score maker, Stefano Paparozzi, his take came one year later... and his version was definitely worth waiting for.

In Paparozzi’s ‘twisted’ version of Für Elise, the score is turned upside down and transposed, so that the left hand now carries the melody. It’s a darker, brooding score, with a disturbing sense of mystery – have a listen below. More tongue-in-cheek viewers have also expressed their delight that Beethoven can “finally be played in Australia!”.

The more creative among the comments section have detailed how this bittersweet imagining of one of Beethoven’s most famous works, would work well as part of a film.

Inverting melodies or turning normally major melodies into minor is a common trick used in film scoring to highlight a change in tone during a story.

Paparozzi’s YouTube channel S.P.'s score videos has over 13,000 subscribers, and his videos of around 1,000 scores range from Baroque to early-20th Century music.

Since the success of his take on Für Elise, the composer has set up a dedicated YouTube channel for his Upside-Down Scores. So far he has taken on the challenge of creating upside-down versions of works by Bach, Chopin, and Mozart.

¡ʇxǝu op noʎ ʇɐɥʍ ƃuᴉǝǝs oʇ pɹɐʍɹoɟ ʞool ǝM

Thursday, January 20, 2022

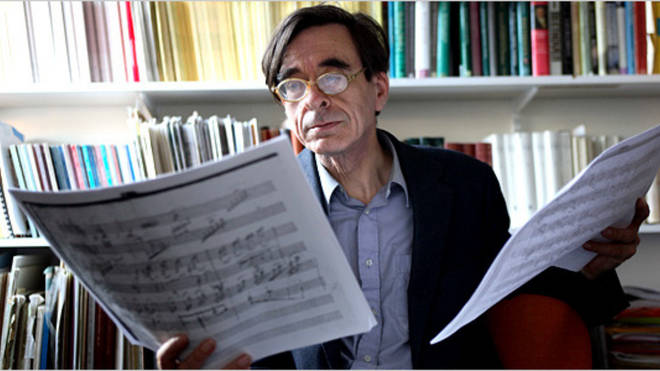

How Beethoven’s iconic ‘da-da-da-dum’ motif was almost lost in a forgotten piano piece

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM London

@sophiassocialsThe UK’s leading scholar on Beethoven has found that the famous opening of the Fifth Symphony began life with a totally different purpose...

Classical connoisseur, and music novice alike will recognise the famous four-note opening motif of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

The ominous introductory theme appears in modern media, such as movies, and was also used during the Second World War as a symbol for Victory. The famed ‘da-da-da-dumm’ motif mirrored the rhythm used for the letter V in Morse code (short-short-short-long).

However, the origins of the opening theme have remained relatively unexplored, or understood; until now.

Thanks to the investigations of Professor Barry Cooper, the UK’s leading scholar on the German composer, it’s been revealed that classical music’s most iconic motif was almost simply a subsidiary theme meant for a forgotten piano piece.

In 1804, four years before the Fifth Symphony’s first performance, Beethoven wrote out the sketches of the opening theme of his next symphony.

Scholars have used this manuscript as a source of sketches for the Fifth Symphony however, thanks to Cooper’s further investigation into the score, it is clear that Beethoven was not in fact sketching a symphony – but a piano fantasia.

“It became abundantly clear to me that [these sketches were] part of the projected piano fantasia, which was being sketched immediately above the sketch in question,” explained Cooper. “I studied the page in detail as I am writing a book on ‘The Creation of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies’.”

Cooper, who is a professor at the University of Manchester, is best known for his books on Beethoven, as well as a completion and realisation of Beethoven’s fragmentary Symphony No. 10.

“The fantasia (so-called in the sketch) is in C minor, like the [fifth] symphony. Like most fantasias of the period, it would be based on contrasting sections and ideas, so the opening section is in a slow 3/8, contrasting with the later 2/4 that uses the motif that ended up in the symphony.

“The motif is then developed in the 2/4 section in a symphonic manner – which may be why Beethoven concluded it would work better in a symphony – but using piano textures rather than orchestral ones, and in a different way from how it is developed in the symphony.”

Professor Cooper notes that the find gives us a deeper understanding of how Beethoven worked as a composer.

“The sketch shows that he was prepared to transfer ideas intended for one composition into a completely different one, if it would work better there.”

Cooper surmises that Beethoven felt exactly that way about this motif, and adds the composer “strengthened the motif by placing it at the head of a symphony, and then strengthened it still further by adding dramatic pauses in later sketches and the final version”.