by

She campaigned to become the first professional woman organist in Sweden, paving the way for countless women after her.

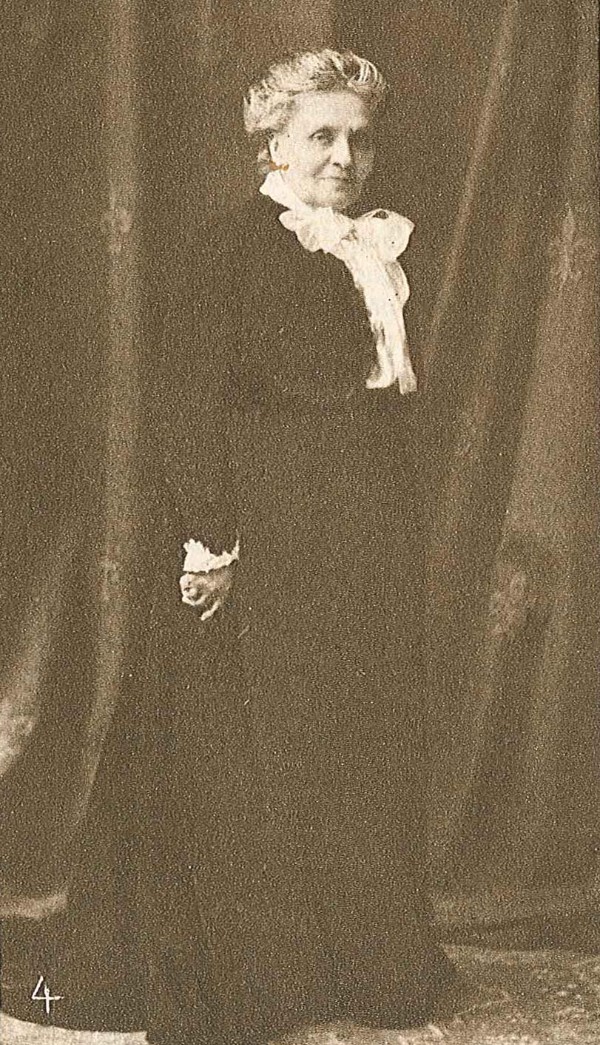

Elfrida Andrée, 1891

But she didn’t stop there: she also became the country’s first woman conductor, as well as an accomplished composer who loved writing orchestral music.

Today, we’re looking at the life and times of Elfrida Andrée.

Elfrida Andrée’s Family

Elfrida Andrée was born on 19 February 1841. Her hometown was the Swedish city of Visby, on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Latvia.

Her father, Andreas Andrée, trained as a medical man and became a ship’s doctor, traveling to ports in Europe, Africa, and Asia. After he returned to Sweden and settled down, he began pursuing an interest in politics.

He became interested in various ideas that were gaining popularity at the time, such as the labour movement and the women’s movement.

The Musical Andrée Daughters

Elfrida Andrée

In 1836, he and his wife had a daughter named Fredrika. A second daughter, Elfrida, was born five years later.

He and his wife, Lovisa, determined they wanted to raise their daughters with liberal values and educate them. Andreas taught both of them how to play the piano and sing, as well as basic lessons in harmony.

Fredrika proved to be a talented vocalist. In 1851, when she was fifteen, she left the household and traveled to study at the prestigious Leipzig Conservatory.

As for Elfrida, she began to study with two local organists, despite that instrument’s masculine reputation. She also took up the harp, although we don’t know who she studied with.

She performed at the local Musical Society (headed by one of her teachers) and at salon performances given at the Andrée household.

Moving to Stockholm

After Fredrika returned from her studies in 1855, she was hired to sing at the opera in Stockholm. Elfrida joined her, while their parents remained in Visby. Fredrika was nineteen, and Elfrida was fourteen.

While in Stockholm, Elfrida took composition lessons with Niels Wilhelm Gade and Ludvig Norman (who would go on to marry Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda, one of the first great women violinists).

In October 1856, a family friend, organist and composer Gustaf Mankell, submitted a request to the Royal Musical Academy in Stockholm, asking to consider Elfrida for admittance. His request was denied, possibly because of her age.

She studied privately with Mankell until she was finally allowed to take the entrance examination in June 1857.

Women Organists in Sweden

However, there was a controversy underlying her acceptance: the Swedish government did not allow women to be organists.

Elfrida could earn a degree, but it would be relatively useless without an accompanying job. To maintain an identity as an organ virtuoso necessitated regular access to an organ and a job to go alongside that access.

Unfortunately for Elfrida’s dreams, many countries banned women from playing the organ in church, citing St. Paul’s admonition that women remain quiet during worship.

So after her acceptance to the Conservatory, a sixteen-year-old Elfrida wrote to King Oscar I of Sweden and Norway, matter-of-factly laying the matter out and requesting that the policy be changed:

The fact that it has long been customary abroad, as in England and France, for women to hold the position of organist gives me the courage and hope to make this most humble request to His Royal Majesty.

She didn’t hear back for quite a while.

Battling with the Government

Elfrida kept studying, and she graduated from the conservatory. But in the spring of 1859, bad news came: a government official had denied her proposal.

One magazine reported:

The government submitted the request to the archbishop, who refused to grant it, mainly because it would constitute a rejection of the order currently in force in the empire, which expressly stipulates that offices and positions should be filled by men who have reached the age of majority. As a result, the government has now also rejected the petitioner.

She continued studying while pondering her next moves. She also began giving piano and organ lessons to help support herself.

In 1859, her parents and younger brother moved to Stockholm. Reunited with Andreas, father and daughter teamed up to try submitting another petition. This one worked.

In March 1861, the Swedish parliament changed the law, opening the profession to unmarried women over the age of twenty-five. (It’s unclear why they granted an age exception to Elfrida, who had just turned 20.)

By May, Elfrida was a professional organist at the Finnish Church in Stockholm: the first in Swedish history.

Telegraph Operator

Elfrida Andrée

Amusingly, at the same time, Elfrida and her father also submitted another envelope-pushing application: for her to become a worker in a telegraph office.

At the time, telegraphy was cutting-edge technology, and women were not allowed to work in the field.

In 1863, her request was approved, but it’s not clear as to what purpose (publicity? activism? or did Elfrida actually seriously consider becoming a telegraphist?). There is no record of her ever working in the field.

Nevertheless, it was an important barrier to break.

Fittingly, around this time she adapted a personal motto: “det kvinnliga släkets höjande”, or “the elevation of womankind.”

The Gothenburg Cathedral

In 1867, a vacancy for organist opened up at the Gothenburg Cathedral. Her father stepped in, writing to the provost that appointing a woman to the position would signal the city’s open mind and liberal spirit.

Elfrida went to audition on 14 April 1867, the weekend before Easter. Seven men auditioned for the position, too, but the committee unanimously elected her to the post. She became the first professional woman organist in Sweden, and one of the first in Europe.

Her remarkable tenure at the cathedral would last for over sixty years. Her duties in Gothenburg included programming and performing organ music at services, as well as maintaining the organ. In 1907, she also became the choir director.

Concertizing in Germany

Elfrida Andrée

Her fame spread. The Gothenburg Trade Newspaper reported on a November 1867 performance:

Miss Andrée’s performance of her solo part on the organ…justifies the decision that has made her organist at Sweden’s largest church.

However, attitudes were not quite so enlightened outside of Gothenburg.

In 1872, she was set to perform at Leipzig’s St. Thomas Church, where Bach had been music director a few generations ago. But the performance ultimately had to be canceled.

She wrote to her father what the appalled pastor told her:

The board had the same feeling that it was not at all appropriate for a woman to play in a church! She would then be alone on the organ with the whole choir! That is not appropriate at all. We have never heard of a female organist in Germany, and that is not possible here in Germany; it is against German custom.

Elfrida Andrée’s Compositions

She faced similar resistance when it came to presenting her compositions.

She was deeply attracted by the idea of composing not just chamber music, but large-scale symphonic works. As early as the 1870s, she wrote, “The orchestra, that is my goal!”

She wrote to her sister Fredrika, “If you could conceive of the ideal light in which the orchestra appears to my sight! It is an interpreter of the wondrous surgings of the soul.”

When legendary singer Jenny Lind expressed doubt to her that a woman could write well for orchestra, Elfrida went to the piano and played extracts of her second symphony for her.

Over the course of her career, she wrote an opera, two overtures, a symphonic poem, two organ symphonies, two masses, and two symphonies.

A Disastrous Premiere

In 1869, when she was twenty-eight, her first symphony was premiered by the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra.

A nightmare scenario played out. Elfrida wrote later:

The performance was terrible, and I think the musicians deliberately played wrong notes. Fredrika and I left when the Finale started, and the first violins were continually behind the rest of the orchestra one entire measure.

After the debacle, even her own supportive father expressed reservations about her obsession with writing for orchestra. She wrote to him, quite firmly:

The popularity of all these little ladies with their piano fantasies or pretty songs is not what I want to do.

She composed a second symphony in 1879, but had to wait years to have an opportunity to hear it performed.

The bad performance of her first symphony and the lag between composition and premiere of her second help to explain why even the most talented women composers in nineteenth-century Europe found it difficult to write symphonies and get them performed.

Triumph in Germany

Elfrida Andrée at 22

In 1887, she made another tour of Germany. This time, she was allowed to perform at the Marienkirche in Berlin, but she had to pay a hundred marks for the privilege (she did).

She conducted during this appearance, marking the first time that Dresden had ever seen a woman conducting her own works.

The press praised her: it was a “brilliant success for Miss Andrée, who was celebrated with stormy applause and a fanfare from the orchestra.”

Later Works

Her second symphony – fourteen years old at this point – was finally premiered in 1893. Happily, this performance went off much better, and the audience demanded the finale be encored.

In 1899, she wrote an opera called the Fritiofs Saga with librettist Selma Lagerlöf, who would go on to become the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Fritiofs Saga was inspired by Norse mythology. Tragically, despite Andrée’s high-ranking position in Swedish music, she was never able to see it fully staged. Ever persistent, she adapted the music into an orchestral suite.

Working as a Conductor

She continued exploring an interest in orchestral music: specifically, conducting it, as well as writing it. Although it was relatively common at the time for a woman to solo with professional orchestras, it was still rare for them to conduct an orchestra.

In 1897, when Elfrida was fifty-six, she became the head of the Gothenburg Workers’ Institute Concerts. Her responsibilities included conducting, which made her the first Swedish woman to conduct an orchestra in public.

But she also assisted by helping to organise the concerts, alongside her sister. The ticket prices were kept low, and audiences from all classes were encouraged to attend.

She presented around eight hundred of these concerts, making her an invaluable part of the cultural life of Sweden.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1904, she returned to Germany for a final time, stopping in Dresden. She set up a performance for organ and orchestra. Again, she had to pay, but the concert was a “brilliant success”, according to the press. It had taken a few decades, but she had finally made her point.

In 1911, Elfrida gave the keynote speech at the International Suffragette Conference in Stockholm.

In her remarks, she declared that it was her aim to “give freedom to the bound…and courage to the frightened.”

She died in Gothenburg in January 1929, shortly before her eighty-eighth birthday.

One account claims that one night, toward the end of her career, she performed on the Gothenberg organ late into the night. After a virtuosic flourish, speaking of St. Paul and his admonition against women making noise in church, she remarked, “Paul, old lad – try that for size!”