Contemporary classical composers you need to discover today

New music of such variety, imagination and originality, there is something here for everyone

Caroline Shaw

What were you doing when you were 30 years old? Caroline Shaw is unlikely to forget, for this was her age when she received the Pulitzer Prize for music. The year was 2013, and the accolade was for her a cappella piece Partita (2009-11) for eight voices. Composed for the vocal group Roomful of Teeth, of which she was (and still is) a member, the work was released on their Grammy-winning self-titled debut album in October 2012. It didn’t receive its full premiere until November the following year, when it was performed by the group at (Le) Poisson Rouge in New York.

Partita for eight voices made Shaw the youngest ever recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for music. And in 2019, The Guardian ranked it as the 20th greatest work of classical music since 2000. All this for good reason – the piece is a vocal joyride. It begins with spoken word: ‘To the side. To the side. To the side and around’ – followed by a wall of harmonised euphoria. It continues with tides of song gathering and then drifting apart; flooding in and falling back. The work as a whole is inventive and pulls out all the stops when it comes to what a mouth and a pair of lungs can do: speech, whispers, sighs, wordless melodies and sundry other vocal techniques. It was inspired by artist Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing 305 – ‘born’, as Shaw says, ‘of a love of surface and structure, of the human voice, of dancing and tired ligaments, of music, and of our basic desire to draw a line from one point to another’.

Anna Clyne

Cultural considerations are not the only things that have recently brought a host of female composers to prominence. Half a century ago the wholly different talents of Lutyens, Maconchy and Thea Musgrave need not have feared comparison with their male contemporaries – a situation mirrored now with the emergence of a new generation on the new music scene, from among whom Anna Clyne is striking for the rapidity with which her output has evolved into a mature idiom always lucid in its compositional craft and immediate in its emotional impact.

Born in London, Clyne studied music at the University of Edinburgh then at the Manhattan School of Music where her tutors included Julia Wolfe – a founder member of the influential ensemble Bang on a Can, which commissioned and performed several of her earlier pieces. Clyne had begun composing around the age of 10, and although the first acknowledged works date from her early twenties, an essentially youthful delight in the discovering as well as realising of unusual combinations of sound is a constant across all her music that emerged at this time.

Hildur Guðnadóttir

Every aspect of a traditional ‘classical’ composer’s craft requires a degree of compromise. Notation, no matter how meticulously realised, can never fully represent the work as conjured in the composer’s imagination; and no performance or recording can ever fully recreate every intention of a score – so it becomes a compromise upon a compromise. This isn’t to say, of course, that the whole business of writing and recording music is a fruitless exercise, it is simply that each element of the process that requires the music to be ‘translated’ into another medium moves the music further from the composer’s initial conception – sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

Advances in the affordability and accessibility of recording technology over the last few decades have made it possible to write and record entire albums’ worth of music from home, practically alone, on nothing more than a laptop. It’s a model that has been widespread in pop music for years, but there are also many composers who are self-producing recordings of great interest to Gramophone readers, and one of the most compelling and successful is Hildur Guðnadóttir.

Errollyn Wallen

An influential figure and inspirational role model for young musicians, respected and admired by fellow composers and performers, and recognised by the pillars of the British musical establishment, Errollyn Wallen is a leading figure in today’s classical music world. But the journey that she has taken has been nothing if not unconventional. Indeed, it could never have been any other way.

She was born in Belize, and at the age of two moved to London with her parents. She became a musician almost by accident, owing to the fact that she came from a musical family: her father was a fine amateur singer who wrote songs and introduced his young daughter to jazz, blues and the recordings of Ella Fitzgerald. Being a keen dancer, Wallen first experienced classical music at a ballet class when an accompanist suddenly started playing Chopin. She was absolutely mesmerised and immediately set about exploring classical music – in both its traditional and its more contemporary forms.

Sofia Gubaidulina

As the Soviet system gradually lost its grip on power through the 1980s, a diverse range of compositional voices was released into the wider musical world. A generation of ‘unofficial’ composers, effectively an underground movement in the 1960s and ’70s, suddenly came to prominence. Western audiences were introduced to the sophisticated polystylism of Alfred Schnittke, the esoteric serialism of Edison Denisov, the serene tintinnabulation of Arvo Pärt – and to Sofia Gubaidulina. Her music was, and remains, difficult to categorise. She is a religious maximalist, who employs an often brutal modernist language to express and explore dimensions of her Christian faith. Her music always seems immediate and spontaneous, yet is underpinned by sophisticated mathematical procedures. And, while she embraces joy, hope and light in her music, she does so via extreme contrasts, often leading her listeners through dark and unsettling places on her very individual path to transcendence.

Gidon Kremer brought Gubaidulina’s music to international attention when he gave the premiere of her violin concerto Offertorium in Vienna in 1981. The Soviet authorities almost succeeded in preventing the concert from taking place, but it was made possible by Gubaidulina’s enterprising Western publisher, Jürgen Köchel, who smuggled the score out of the country to get it to Kremer. The premiere was a great success, and Kremer continued to spread the word in the following years, giving performances of the concerto with leading orchestras around the world.

Jennifer Higdon

'Jennifer Higdon’s myriad accolades and accomplishments are impressive by any standard, but particularly in the world of contemporary classical music. She’s won a Pulitzer Prize and a Grammy Award. Her music is in such high demand that she’s able to compose exclusively on commission. And her champions include top-tier soloists, ensembles and orchestras. According to a recent survey of US orchestras, Higdon is one of the most performed living American composers.

'Yet Higdon’s most striking achievement doesn’t fit so easily into a biography, and that’s how thoroughly her music has filtered into every stratum of classical music culture in the United States. Glance through the ‘Upcoming Performances’ page of her official website and you’ll find that her work is being played not only by the Houston Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra, but also by municipal, community, and high school ensembles across the country. On the surface, it appears to be a simple formula: Higdon writes music that audiences like to hear and musicians find gratifying to play. But is it really so simple?..'

Lera Auerbach

'In an age of multitasking habits, polymodal perceptions and multisensory experiences, we are all now expected to become polymaths. As Vinnie Mirchandani put it in his preface to The New Polymath (Wiley: 2010): ‘[We] can no longer be just one person but a collection of many.’ But in trying to become too many people, what is lost? Identity, depth, talent? Genius, perhaps?

'Lera Auerbach is a polymath in the original sense of the word – as defined and defended by Renaissance writers and thinkers; but she is also very much an artist of her time. Apart from being a successful composer and concert pianist, she’s a painter, sculptor, librettist and author of several books of poetry and prose, but for Auerbach these extramusical activities are not exercises in dilettantism: all art forms are interconnected and designed to nourish and sustain each other...'

Sally Beamish

'In a way, music was Sally Beamish’s first language. Her mother, a violinist, taught her to read and write notes at the age of four – before she could play an instrument, before she could even read or write words. She would draw little flowers or faces on the manuscript and her mum would interpret how the graphic notation might sound. ‘I always wanted to make my own stuff,’ she says. ‘I’ve made my own clothes, written stories, painted…’ When she started learning piano aged five, she constructed herself a little exercise book.

'Today Beamish is one of the UK’s busiest and most warmly respected composers, with commissions coming in thick and fast for scores ranging from large-scale ballet and oratorios to chamber, theatre and solo works. At 60 she already has a catalogue of more than 200 pieces and that number is rising fast: this year she has been writing three piano concertos, among several other projects. For many listeners, the great appeal of Beamish’s music is the space it finds between softness and steel – her knack of blending folk-flecked lyricism, emotional candour, a sense of the natural world and a propulsive way with rhythm plus real economy, directness, luminous orchestrations and rigour of craft. She’s the kind of composer who seems to know exactly what she wants a piece to say and finds the most compassionate and least fussy way of saying it...'

Augusta Read Thomas

'American classical music this past quarter-century has been dominated by the minimalist aesthetic that came to the fore as a reaction against the modernist thinking which had previously held sway. Currently it represents a virtual lingua franca in terms of its influence on mainstream composers. Others, however, have looked back (not in anger and still less out of nostalgia) to an era in which aspects of modernism were linked to a freely evolving tonality so that new possibilities were opened up for exploration. Only recently has this approach regained prominence, with Augusta Read Thomas being among its leading exponents.

'Born in Glen Cove, Long Island, in April 1964, Thomas studied at Yale University and later at the Royal Academy of Music in London and Chicago’s Northwestern University. To speak of influences is often unnecessarily subjective, yet two composers with whom she came into contact during this period were to leave their mark on her music in the most direct and positive sense. From Jacob Druckman (1928-96) she absorbed the value of instrumental colour as a formal and expressive component rather than just an external dressing, while in Donald Erb (1927-2008) she had the example of an orchestrator who was second to none in this respect among American composers of his generation. What this gave to Thomas’s music from the outset was its clarity of conception and precision of gesture (whether in the briefest of instrumental miniatures or in large-scale orchestral works), which act as the focus for her often intricate textures and iridescent harmonies – thereby ensuring that her work exudes an immediacy and a communicativeness whatever its degree of complexity and dissonance...'

Unsuk Chin

'Curiouser and curiouser. Listening to the music of Unsuk Chin can feel like an adventure in Alice’s Wonderland. We start in familiar territory, with simple and attractive musical ideas, but these gradually weave into complex and unsettling textures. Soon we are down the rabbit hole, and nothing is quite what it seems. The music appears stable, until a subtle change in harmony casts it in an entirely new light. Perspectives change, motifs and melodies twist and distort. Simplicity gives way to beguiling complexity. Then everything stops, often with a thump from the percussion, and we are left contemplating the bizarre turn of events. Was it all a dream?

'Unsuk Chin has been fascinated by Alice in Wonderland since childhood, and it has inspired much of her music, most notably her 2007 Alice opera. But her take on the story is distinctive. The opera is full of moments of intrigue and wonder, but these are set against stark representations of the tale’s brutal absurdity – a fantastical yet always lucid conception, typical of Chin. As a Korean based in Germany, she has an outsider’s perspective on European culture, and her music regularly highlights its ingrained paradoxes. She is a voice of reason, bringing order to the surreal. Above all, she brings clarity, however complex her music becomes, with every note remaining audible, every motivation clear...'

Anna Thorvaldsdóttir

Before notating her works conventionally via the five lines of the musical stave, Anna Thorvaldsdóttir literally draws them. The pristine pencil illustrations this process spawns are something to behold. One of them is reproduced on the cover – and inside the booklet, in a more complete version – of what was the first album to feature her music and her music alone: Rhízoma.

The drawing features a consistent yet bumpy horizon of two almost-horizontal lines in counterpoint. Beneath that, multiple roots gather towards a single, thick trunk before breaking into four branches, fraying outwards at their end points (it could be a forbidding volcano; it could be a weedy turnip). Thoughts in text form are scattered around in meticulous block capitals: ‘In constant development’ / ‘Bell like’ / ‘I predict that the duration of this piece will be approximately 12-14 minutes’.

Speaking at an open question-and-answer session in Copenhagen in January, Thorvaldsdóttir explained that she uses drawings like these as compositional aids, devices for ‘mapping where a piece is going’. But they contain vital structural clues for the rest of us. In the case of this particular drawing – an image of the piece Streaming Arhythmia (2007) – we can trace how the biology of subterranean roots or ‘rhizomes’ has influenced the development of the music. The sketch also bears an uncanny resemblance to the landscape of Thorvaldsdóttir’s Iceland: a barren and highly atmospheric terrain characterised by black rock, dark moss, starkly outlined volcanic peaks and a total lack of trees.

Olga Neuwirth

The music of Olga Neuwirth (b1968) is richly allusive, moving freely between reference points as varied as Monteverdi, Weill, Miles Davis and Klaus Nomi. She has cited influences from Boulez to the Beastie Boys. Yet if there’s one artist whose aesthetic approach seems particularly close to hers, it isn’t a musician at all – it is film-maker David Lynch, the maverick director behind such cult classics as Twin Peaks (1990-91; 2017), Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001). Bizarre juxtapositions, surreal narrative twists, vivid images of obscure significance: his films are not just strange but also uncanny – even inexplicable at times – as they journey into dreamlike worlds in which the standard rules of time, space and sense seem to drift away. Music may be a more abstract medium than film, but Neuwirth’s work proves its ability to be just as fascinatingly unfathomable. Her music is enthralling and provocative not despite its strangeness, but because of it.

The Lynch comparison is one that Neuwirth provoked herself when she turned Lost Highway, the film that some call Lynch’s very strangest, into an opera in 2002-03, in collaboration with her Nobel Prize-winning compatriot Elfriede Jelinek. It is hard to imagine a more audacious choice of film to receive the operatic treatment, but Neuwirth’s fragmentary, multidimensional music creates something that somehow does seem to be the kindred spirit of the original. At one point in both film and opera (some time before he inexplicably transforms into a car mechanic), the protagonist Fred explains why he doesn’t own a video camera. ‘I like to remember things my own way,’ he says. ‘How I remembered them. Not necessarily the way they happened.’ Perhaps the opera takes a similar approach in adapting the film, twisting it into new shapes – hyper-expressionist vocal acrobatics for one character, deadpan spoken word for another, eerie falsetto vocalise for a third – while retaining the plot and enhancing the noir undercurrent. In fact, perhaps that is what all opera does anyway, taking the kernel of a story and heightening its intensity through clipped lines of text and sweeping currents of music. To be sure, opera seldom portrays events ‘the way they happened’.

Kaija Saariaho

Kaija Saariaho (b1952 in Helsinki) is one of the foremost women composers on the planet and one of the leading creative figures of her generation of either gender; a truly original artist with a very distinctive musical style and personal voice, developed and refined over decades. The awards she has received over the years are indicative of this, including the Kranichsteiner Prize (1986), the Nordic Council Music Prize (2000, for Lonh), the Grawemeyer (2003, for her first opera, L’amour de loin), the Nemmers Prize in Composition (2007), the Wihuri Sibelius Prize (2009) and the Léonie Sonning Music Prize (2011).

Yet she is also a very private person, with much about her biography that is largely unknown, not least that she was born Kaija Laakkonen: the ‘trademark’ name of Saariaho is her first husband’s. She studied with Heininen at the Sibelius Academy, with other members of a miraculous generation of Finnish composers including Esa-Pekka Salonen and Magnus Lindberg. Further studies followed with Brian Ferneyhough and Klaus Huber; equally formative influences were Tristan Murail and Gérard Grisey, the principal exponents of spectral music (music placing timbre and sound ahead of other compositional considerations), leading her to IRCAM and 30 years’ residence in Paris, latterly with her second husband, Jean-Baptiste Barrière. Although she made an initial breakthrough with the orchestral Verblendungen (1984), it was with her dazzling, enchanting nonet-with-electronics Lichtbogen (‘Arches of Light’, 1986) that she burst onto the wider scene. Its ethereal, hypnotic textures were inspired by the aurora borealis, and the use of electronics proved prophetic for her future career. More important still was the combination of sonic delicacy and an inner steel – which makes her works beguiling to the ear yet robust and compelling as structures.

Thea Musgrave

Asked once whether she had any advice for young composers, Thea Musgrave replied: ‘Don’t, unless you really have to; then you’ll do it anyway.’ Musgrave – the Scottish composer, conductor, pianist and teacher who turns 90 this month – has lived by her own advice. There’s a clear-sighted rationality to her approach, to the way she speaks about her music, to the way she adheres to deadlines and writes practical, non-fussy scores that endear her to commissioners and orchestral musicians.

But beneath the pragmatism, Musgrave’s music is all about drama. Whether in her searingly perceptive operas or her non-narrative instrumental works, she has long been fascinated by the innate drama of human behaviour: the psychological dance of conversation, interaction, confrontation and appeasement. She’s a composer who recognises that music mirrors life, that music can shape the way we live, that the emotional and even physical makeup of musicians is integral to the impact of any performance. To put it simply, her work speaks directly and compassionately about all of us. ‘There are basic human truths,’ she says, and it is those truths that she probes in her music.

Roxanna Panufnik

There’s a different kind of revolution taking place in today’s contemporary music, and at its heart lies Roxanna Panufnik. Hers is not a radical revolution designed to overhaul the old order completely, à la Schoenberg or Cage. Instead, here is a quiet revolution that utilises music’s power to unite people from different cultures, religious backgrounds and political persuasions: a revolution that is more John Lennon than John Cage.

In Panufnik’s own words: ‘I’m on a mission to shout from the rooftops the beauty of all these different faiths’ music. It’s about bringing us together. Too often we don’t think about what we have in common, but instead about our tiny fraction of difference from each other.’

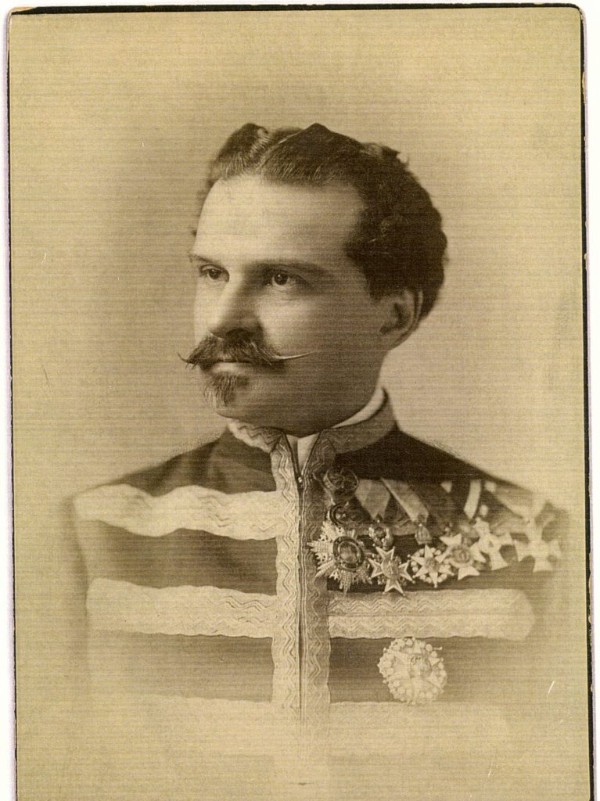

The importance of music’s social and political function was, of course, not lost on Roxanna’s father. The well-known, much admired and highly regarded Polish composer Sir Andrzej Panufnik (1914-91) was forced to escape the oppressive post-war climate of his native country in 1954. He arrived in London and some nine years later married author and photographer Camilla Jessel. Roxanna was born in 1968.