Us, too. But of course, there’s no way to objectively measure who “the best” teachers are. (Surely the best teachers in your life are the incredible men and women who have taught you over the years.)

Nevertheless, we wanted to try to put together some kind of list addressing the question, so today we’re looking at eight candidates.

If a teacher worked with over half a dozen famous names, they became a candidate for this list. From there, we looked at who had the most impact on the art. After that, we made some subjective choices.

It goes without saying, it was a hard job to narrow a list down to the top eight, but here’s our best shot at it, presented in rough reverse order of influence and importance.

Let us know if you think we got our ranking wrong (or right!).

8) Maria Curcio

Pupils: Martha Argerich, Myung-whun Chung, Simone Dinnerstein, Leon Fleisher, Radu Lupu, Mitsuko Uchida

Maria Curcio – piano teacher, her life and musical philosophy (part 1)

Maria Curcio was born in the summer of 1918. Her father was Italian, and her Jewish-Brazilian mother was a talented pianist.

She began playing piano when she was three years old and was consequently barred by her parents from having a normal childhood. She enrolled in the Naples Conservatory when she was nine years old and graduated at fourteen.

An important moment in her artistic development came in 1933, when she auditioned for the studio of influential pianist Artur Schnabel. Initially, he didn’t want to accept such a young pupil, but when he heard her, he was flabbergasted and claimed she was “one of the greatest talents I have ever met.”

Maria Curcio

In 1939, barely twenty years old, she followed Schnabel’s Jewish secretary Peter Diamand on tour to Amsterdam. While they were there, World War II broke out, and soon the city fell under Nazi control.

The couple went into hiding. Between the stress, poor nutrition, and a tuberculosis infection, Curcio ended the war very sick. The chronic health issues that developed afterwards derailed her performing career for over a decade.

Effectively barred from a performing career, she began teaching more and more. Her studio witnessed a number of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century, and her legacy lives on through them today.

7) Franz Liszt

Pupils: Eugen d’Albert, Hans von Bülow, Amy Fay, Agathe Backer Grøndahl, Sophie Menter, Carl Reinecke, Pauline Viardot, and countless others.

Today, Franz Liszt is remembered primarily as a composer and virtuoso who revolutionised piano technique. But he was also a hugely important mentor for countless nineteenth-century musicians.

According to student Amy Fay, who wrote a book about her European training, Liszt hated being thought of as an official teacher. His teaching arrangements tended to be loose and informal.

But he was incredibly generous with his time and attention, and even those musicians he never taught “officially” soaked in his artistry and technique via listening and conversation. They, in turn, shared what they had learned with their students. His legacy continues today.

In the words of Fay:

Under the inspiration of Liszt’s playing, everybody worked “tooth and nail” to achieve the impossible. A smile of approbation from him was all we cared for. This is how it is that he turned out such a grand school of piano-playing.

He was not afraid, and his pupils are like him. They are not afraid, either, and it is they who have revealed Liszt’s beautiful compositions and brilliant concert style to the world.

It is the direct inheritance of his teaching and example, and even his least eminent pupils have caught something of Liszt’s largeness of horizon.

6) Johann Georg Albrechtsberger

Pupils: Ludwig van Beethoven, John Field, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Ignaz Moscheles, Anton Reicha

Johann Georg Albrechtsberger taught some of the most influential teachers of the nineteenth century, but he is little-known today.

He was born just outside of Vienna in 1736. Initially, he pursued a career in church music. Later, his facility with compositional technique made him a popular teacher in Vienna.

In 1790, he wrote a treatise on compositional theory. After his death, his writings on harmony were published posthumously. These works remained in print for many years.

He died in 1809, never witnessing the full flowering of his best students’ potential.

Johann Georg Albrechtsberger

Without knowing it, Albrechtsberger laid the groundwork for the Romantic era: the revolutionary compositions of Beethoven; the emotional and virtuosic piano playing of Field, Kalkbrenner, and Moscheles; and the pedagogical influence of Anton Reicha, whose time working at the Paris Conservatoire in the 1830s made a huge impact on French music.

5) Carl Reinecke

Pupils: Isaac Albéniz, Max Bruch, Ferruccio Busoni, Edvard Grieg, Leoš Janáček, Amanda Röntgen-Maier, Ethel Smyth, Charles Villiers Stanford

Romantic era music also owes a huge debt to the pupils of Carl Reinecke.

Reinecke was born in the city of Altona, Hamburg, in present-day Germany in 1824. Working under his musician father, he began composing at the age of seven. He gave his first public performance on the piano when he was twelve.

As a young man, he moved to Leipzig, Germany, where he studied under Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn, and Franz Liszt.

Carl Reinecke

In 1860, when he was in his mid-thirties, he was named to the music directorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. He also took a position teaching piano and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory.

Over his decades of working as a teacher, a truly amazing array of pupils came through his studio, including many who composed in diverse styles influenced by the rising tide of nationalism in music.

Albéniz wrote famously Spanish music; Grieg, of course, took great inspiration from the folk music of Norway; Janáček became one of the most famous Czech composers ever; and Ethel Smyth and Charles Villiers Stanford helped to set the stage for a turn-of-the-century renaissance in British music.

4) Antonio Salieri

Pupils: Ludwig van Beethoven, Carl Czerny, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Franz Liszt, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Ignaz Moscheles, Maria Theresia von Paradis, Franz Schubert

Thanks to the movie Amadeus, Antonio Salieri is unfairly remembered as “the jealous composer who murdered Mozart.” (There is no evidence that he ever did such a thing.)

He was born in 1750 near Verona in present-day Italy. He began studying the violin with a musically talented brother, and moved to Vienna when he was sixteen.

Antonio Salieri painted by Joseph Willibrord Mähler

He eventually worked his way up to become the preeminent composer of Italian opera in Vienna during the late eighteenth century. (Mozart, being a native-born Austrian, was jealous of Salieri’s success.)

In addition to being a well-respected opera composer, he was also a sought-after teacher. Over the course of his career, he ended up tutoring some of the biggest names in nineteenth-century music, including Beethoven, Liszt, Meyerbeer, and Schubert. During these lessons, he usually focused on addressing vocal writing.

Sadly, Salieri’s mental and physical health declined in his later years. He attempted suicide in 1823 and suffered from dementia until his death in 1825. The monument at his grave is decorated with a poem written by one of his pupils, Joseph Weigl.

3) Dorothy DeLay

Pupils: Sarah Chang, Nigel Kennedy, Anne Akiko Meyers, Midori Goto, Shlomo Mintz, Itzhak Perlman, Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, Gil Shaham, Jaap van Zweden

The last fifty years of violin playing would be unrecognisable without the pupils of Dorothy DeLay.

DeLay was born in small-town Kansas in 1917 to a musical family. She began playing the violin when she was four.

She studied at Oberlin Conservatory, Michigan State University, and Juilliard. In 1946, she began working at Juilliard as violin teacher Ivan Galamian’s assistant.

From there, she became an increasingly influential presence. She was deeply beloved for her curiosity, collaborative spirit, and willingness to let her students all develop their own unique creative voices.

Itzhak Perlman, arguably her most famous student, once described her teaching style:

I would come and play for her, and if something was not quite right, it wasn’t like she was going to kill me.

She would ask questions about what you thought of particular phrases—where the top of the phrase was, and so on. We would have a very friendly, interesting discussion about ‘Why do you think it should sound like this?’ and ‘What do you think of that?’

I was not quite used to this way of approaching things.

She died in 2002 at the age of eighty-four. She had led one of the most remarkable teaching careers in the entirety of classical music history.

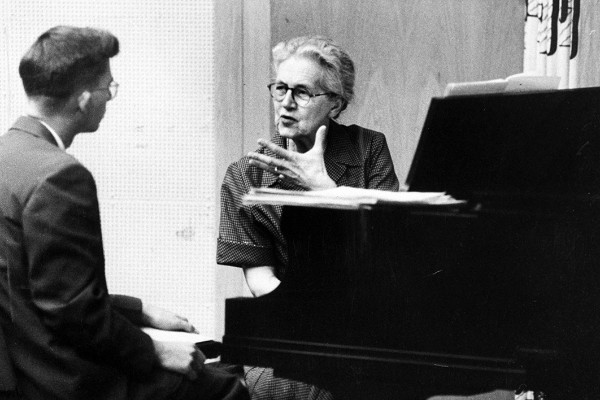

Dorothy DeLay and Midori Goto

2) Mathilde Marchesi

Pupils: Suzanne Adams, Frances Alda, Emma Calvé, Ada Crossley, Emma Eames, Marie Fillunger, Mary Garden, Gabrielle Krauss, Blanche Marchesi, Nellie Melba, Emma Nevada, Sibyl Sanderson

Mathilde Marchesi was born Mathilde Graumann to a musically talented family in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1821.

Her pianist aunt Dorothea von Ertmann was one of Beethoven’s most beloved pupils and creative partners. After his death, Dorothea championed his music, helping to usher it into the canon.

When she was in her early twenties, Mathilde’s family lost their fortune, so she went to seek hers in Vienna and Paris as an opera singer. She made her debut in 1844, but never became a star.

Instead, she married baritone Salvatore Marchesi in 1852, retired from the stage, and shifted her attention to teaching.

Mathilde Marchesi

She began her teaching career working at the conservatories in Cologne and Vienna. In 1881, when she was sixty, she began her own school in Paris.

She specialised in teaching the bel canto style and valued a more natural attitude than was common at the time.

It is mind-boggling how many famous students she taught. Frances Alda (born 1879) became a famous onstage partner of Caruso. Emma Calvé (born 1858) was considered to be the greatest Carmen of her generation. Ada Crossley (born 1871) was the first recording artist hired by the Victor Talking Machine Company. Mary Garden (born 1874) premiered the role of Mélisande in Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande. Sibyl Sanderson became one of Jules Massenet’s favourite performers, and she created the role of Thaïs. Dame Nellie Melba (born 1861) was possibly the most famous singer of the Victorian era, period.

The depth and breadth of the accomplishments of her students, and the way they influenced late nineteenth and early twentieth century opera, makes Mathilde Marchesi one of the best teachers in classical music history.

1) Nadia Boulanger

Pupils: George Antheil, Daniel Barenboim, Marion Bauer, Lili Boulanger, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Gian Carlo Menotti, Ginette Neveu, Astor Piazzolla, Julia Perry, Walter Piston, and countless others

How Nadia Boulanger Raised a Generation of Composers

Nearly every classical music lover can agree: Nadia Boulanger has been the single most influential teacher in classical music history. It’s possible that she’s one of the most influential teachers of all time, period.

Nadia was born in Paris in 1887 to a musical family. Her elderly father, Ernest Boulanger (she was born on his 72nd birthday), was a composer and pianist.

Nadia began studying music when she was five years old. When a sister named Lili arrived five years later, Nadia became devoted to her and her education, too.

Both sisters were incredibly gifted, but Lili was a once-in-a-generation talent. Accordingly, when Nadia began studying at the Paris Conservatoire when she was nine, Lili tagged along with her.

Nadia Boulanger

Nadia dreamed of winning the prestigious Prix de Rome prize: something her father had done in his youth, but which a woman had never done. She came close, but never actually won. Lili ended up breaking that particular glass ceiling in 1913.

Despite her promise, Lili’s health was extremely poor, and she died of Crohn’s disease at the end of World War I.

After her sister’s devastating death, Nadia began gravitating more and more toward teaching instead of composing. She also needed to focus on a field that would guarantee a steady income, in order to support herself and her mother. Consequently, in 1921, she began teaching harmony at the French Music School for Americans in Fontainebleu. One of her first students there would become one of her most famous: Aaron Copland.

Copland would later write of her:

Nadia Boulanger knew everything there was to know about music; she knew the oldest and the latest music, pre-Bach and post-Stravinsky.

All technical know-how was at her fingertips: harmonic transposition, the figured bass, score reading, organ registration, instrumental techniques, structural analyses, the school fugue and the free fugue, the Greek modes and Gregorian chant.

Nadia was blunt about her talent for analysis:

I can tell whether a piece is well-made or not, and I believe that there are conditions without which masterpieces cannot be achieved, but I also believe that what defines a masterpiece cannot be pinned down. I won’t say that the criterion for a masterpiece does not exist, but I don’t know what it is.

Her decades of teaching were not without controversy. She could be emotionally abusive and held ideas that today would be considered offensively sexist. She was also accused of advancing students whom she liked personally and making other students’ lives miserable.

Despite those and other shortcomings, she is unquestionably the most influential music teacher of all time. Classical music as we know it today would not exist without her, period.

No comments:

Post a Comment