It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, December 26, 2025

Happy New Year 2026 🎉 Best New Year Piano & Orchestra Instrumental Covers

For The Patron: The Jour de Fête Quartet

by Maureen Buja

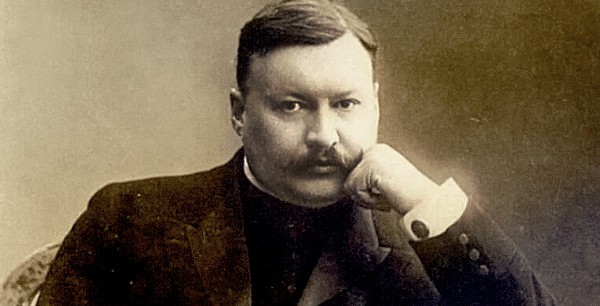

On Fridays, the publisher Mitrofan Petrovich Belaieff had his musical gatherings, bringing together the cream of the St Petersburg composers. The earlier group, who came together around Mily Balakirev, known as the Mighty Handful, or just The Five (Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), had done their best to embody Russian national music, but fell apart after the early death of Mussorgsky. The timber merchant Belaieff stepped forward next.

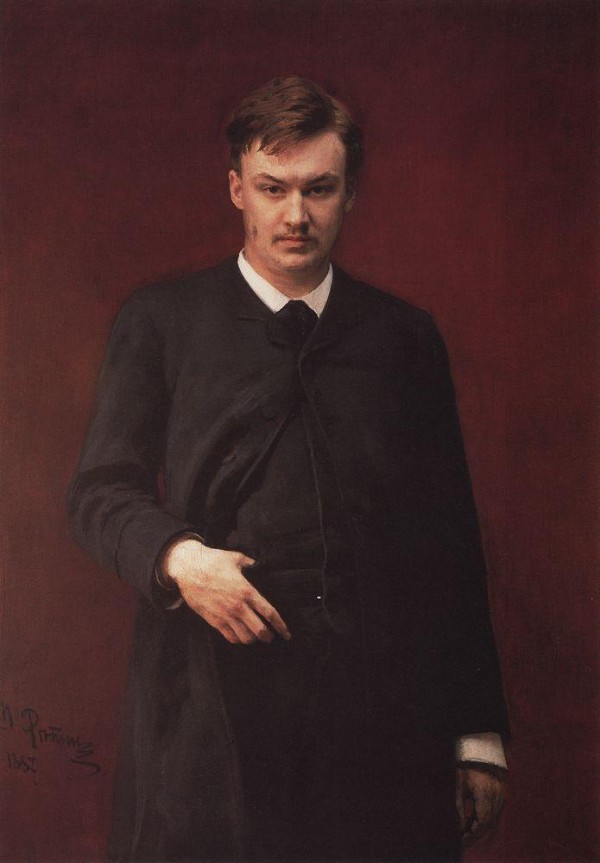

Portrait of Alexander Glazunov

Belaieff, with the family fortune in the timber industry behind him, was also a musician. He played the viola and, through Anatoly Lyadov, was introduced to Alexander Glazunov. In the early 1880s, Belaieff held Friday musical meetings for string quartet concerts at his house. Initially, they were playing through the quartets of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven in chronological order, but soon Russian music was making its appearance.

Portrait of Mitrofan Belaieff by Ilya Repin

Musically, Glazunov was the new driving force behind what became known as the Second Petersburg School. Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, Glazunov, the critic Vladimir Stassov, and many others flocked to Belaieff’s soirees. Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, and Stassov had been important members or adjuncts to The Five. The Belaieff meetings were never cancelled. Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that if a member of the original quartet fell ill, Belaieff quickly found a stand-in. Belaieff always played the viola in the quartet.

A normal evening would include a concert at around 1 am, after which food and wine flowed. After the meal, Glazunov or someone else might play the piano, either trying out a new composition or reducing a symphonic work to a 4-hand version.

The composers would all contribute to a group project, such as the string quartet for Belaieff’s 50th birthday in 1886, composed by Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Lyadov, and Glazunov. Called the String Quartet on the Theme ‘B-la-F’, using the principal syllables of Belaieff’s last name. A year earlier, Glazunov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov composed the three-movement ‘Jour de fête’ or ‘Name-Day Quartet’ for their patron.

For the Jour de Fête quartet, Glazunov contributed an opening movement called Les chanteurs de Noël. The Jour de Fête celebrates Christ’s birth, celebrated on January 6-7 on the Orthodox calendar. The Christmas singers bring joy to the festivities.

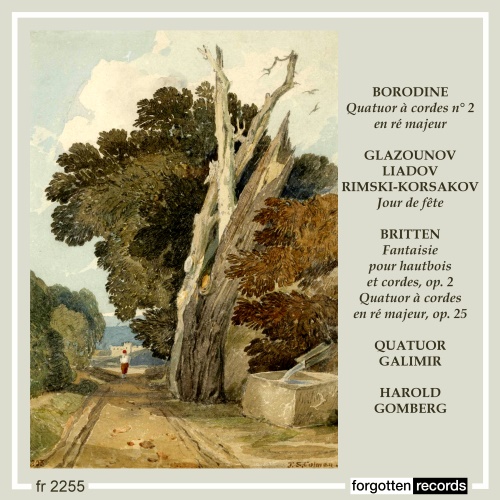

Felix Galimir at Marlboro

This recording was made in 1950 by the Galimir Quartet. Founded by violinist Felix Galimir (1910–1999) in 1927, the quartet was made up of him and his three sisters (Adrienne on violin, Renée on viola, and Marguerite on cello). They were the right quartet at the right time, recording Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite and the String Quartet of Maurice Ravel under the supervision of the composers, who were present during the rehearsals and recording sessions in 1936. These recordings were awarded two Grand Prix de Disques awards. After fleeing Germany because of his Jewish background, he ended up in Palestine and, together with his sister Renée, was a founding member of what would become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1938, he moved to New York, where he re-founded the Galimir Quartet, this time with members Henry Seigl on violin, Karen Tuttle on viola and Seymour Barab on cello. In New York, he was a member of the NBC Symphony orchestra, concertmaster of the Symphony of the Air, and taught at The Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and Mannes College of Music in New York. In the summers, from 1954 to 1999, he was on the faculty of the Marlboro Music Festival.

Performed by

Galimir Quartet

Recorded in 1950

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for o

Khatia Buniatishvili: Master Pianist or Master of Hype?

By Georg Predota

Khatia Buniatishvili © Gavin Evans

She has been called a “social-media pianist,” accused of cultivating an image at the expense of musical depth. These opposing narratives often clash more loudly than the music itself, revealing as much about our cultural anxieties as about Buniatishvili’s artistry.

Yet somewhere between the extremes lies a far more interesting story. How does a singular performer navigate the fault line between genuine expression and hyper-visibility of the modern classical world?

Self-Made Spotlight

What often gets lost in these polarised assessments is just how shrewd Buniatishvili has been in shaping her career. Long before the magazine covers and viral clips, she had already proven her musical calibre, placing respectably in major piano competitions and earning the approval of figures who cared little for glamour.

Yet she also understood, perhaps earlier than many of her peers, that she wasn’t playing in the same league as Yuja Wang, Daniil Trifonov, or Grigory Sokolov. The era in which runner-up prizes alone could propel a pianist to international prominence was clearly fading.

Rather than waiting for gatekeepers to grant her visibility, Buniatishvili seized the tools of modern media and made herself visible on her own terms, not as a shortcut around musicianship, but as a parallel pathway to an audience that the old model no longer reliably delivered.

Crafting a Persona

Khatia Buniatishvili

Central to this recalibrated path was her self-fashioned image, an image she cultivated with unmistakable intentionality, and something she calls “authentic vulnerability.” Buniatishvili understood that in an age saturated with content, visibility alone was meaningless unless it carried emotional charge.

So she leaned into what audiences already sensed, particularly her intensity at the keyboard, her kinetic presence, the way she seemed to play through emotion rather than merely shaping it. The visual language she adopted, including touches of cinematic glamour, was simply a way of amplifying the magnetism that was already there.

It made her instantly recognisable, fiercely memorable, and yes, sometimes controversial. But it also signalled an artist unafraid to fuse musical vulnerability with a boldly curated aesthetic that challenged long-standing expectations about virtuosity.

Digital Glamour

All of this, however, circles back to an essential point. Buniatishvili can play; everybody can these days. And she often plays with a fluency and fire that justify her broad popularity. Her sound is unmistakable, her instincts bold, and when she connects with a work, the result can be genuinely thrilling.

But the amplification provided by social media does not, in itself, confer artistic genius. Visibility is not vision. Followers are not proof of interpretative depth. The danger lies in confusing the mechanisms that propel a career with the qualities that define a great musician.

Buniatishvili’s online presence may magnify her allure, but it cannot substitute for the hard currency of musical insight. This distinction is increasingly difficult to ascertain, yet vital to maintain in the digital age.

Dual Virtuosity

Khatia Buniatishvili

In the end, Khatia Buniatishvili occupies a curious and unmistakably modern position in the classical music landscape. She is, by any reasonable measure, an able and often compelling pianist. She is certainly capable of moments of real eloquence, technical ease, and emotional charge.

But her true virtuosity may lie not only in her playing but in her ability to navigate and manipulate the currents of contemporary visibility. In a field still negotiating its relationship with image, immediacy, and digital spectacle, she has turned self-promotion into an art form of its own.

Khatia Buniatishvili has shaped her persona just as meticulously as any performance. Whether one admires or resents this dual mastery, Buniatishvili stands as a reminder that in the twenty-first century, artistry and self-fashioning travel side by side. Does hype outstrip substance? Time will tell; the debate continues.

Sunday, December 21, 2025

REMASTERED: Yunchan Lim 임윤찬 – RACHMANINOV Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor

A Winter Solsteice - The New Light Symphony Orchestra - The Mantovani Ex...

Instrumental Christmas Music With Fireplace 🔥 Peaceful Christmas Ambience

Relaxing Pinoy Christmas Classic Orchestra - Pinoy Holiday Music

Friday, December 19, 2025

25 Beautiful Classical Pieces That Relax Your Soul and Heart 🎼 .

Dance, Dance, Dance: The Baroque Dance Suite

by ,Maureen Buja

In the new series on dance music, Dance, Dance, Dance, we’ll be looking at dance and how it comes into classical music. You’re going to be surprised at some of the places where it has made an appearance.

We’ll start with not the oldest dances, but with some of the most familiar. In the Baroque era, the dance suite was one of the most popular forms of instrumental music. Pairing of dances was common in the medieval period, but it wasn’t until the 17th century that the keyboard virtuoso Johann Jakob Froberger codified the movements of the suite to include four specific dances: the Allemande, the Courante, the Sarabande, and the Gigue.

Each dance came from a different country and had a different tempo and time signature so that along with the variety of country styles, each dance had its own character.

As its name indicates, the Allemande comes from Germany. It started as a moderate duple-meter dance but came to be one of the most stylized of the Baroque dances. In its earliest versions it was simply called ‘Teutschertanz’ or ‘Dantz’ in Germany and ‘bal todescho’, ‘bal francese’ and ‘tedesco’ in Italy.

Guillaume: Allemande, 1770

It is often paired with a following Courante (from France). When the Allemande was a dance, it was performed by dancers in a line of couples who took hands and then walked the length of the room, walking 3 steps and then balancing on one foot. Musically, the allemande could be quite slow, such as in this piece by Johann Jakob Froberger. Since it was originally intended as a walking piece, the tempo is understandable.

As the century went on, however, the Allemande became faster and eventually functioned like prelude, exploring changing harmonies and moving through dissonances.

In England, the Allemande, or, as it was known there, the Almain or Almand, also became a part of the repertoire. Although this example is short, it could have been repeated multiple times.

By the 18th century, the allemande could get to be quite lively. It has gotten disassociated with its dance and exists solely as a musical form.

In the Baroque suite, the Allemande was followed by the contrasting Courante (from France). The name, derived from the French word for ‘running,’ is a fast dance, performed with running and jumping steps. Following the Allemande in duple meter, the Courente was in triple meter.

In his 17th-century collection Terpsichore, German composer Michael Praetorius collected 312 pieces of dance music, for 3-5 unspecified players. This collection of French dances brought together music of the latest fashion, ‘as played and danced in France’ and that was ‘used at princely banquets or particular entertainments for recreation and enjoyment’. The three courantes here show the different ways one style could be changed.

J.S. Bach used Allemande / Courante pairs in his Partitas and we can hear again that the tempos are contrasting, but really too fast for dancing.

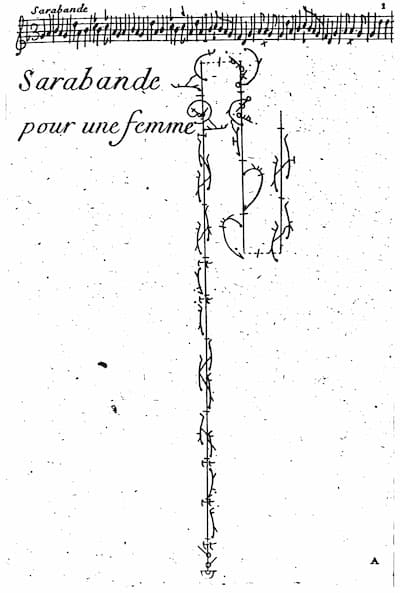

The next dance in the Baroque Suite came from Spain, the Sarabande. It started as a sung dance in Spain and Latin America in the 16th century and by the 17th century, was part of the Spanish guitar repertoire. The Spanish line of development means that it also had Arab influences. As a dance, it was usually created by a double line of couples who played castanets. Once the sarabande got to France, however, what had begun as a fiery couples’ dance changed character completely. It slowed in time, and gradually became a work that might be described as the intellectual core of the Baroque suite.

Fritz Bergen: The Sarabande, 1899

And in a more stately manner:

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Women’s steps for the beginning of the Sarabande, 1704

The final element of the Baroque dance suite was the English Gigue (or jig). This was a fast dance in 6/8 time that was paired with the slower sarabande. Jigs have been known since the 15th century in England, but as it reached the continent in the 17th, is divided into distinct French and Italian versions. The French gigue was moderately fast with irregular phrases.

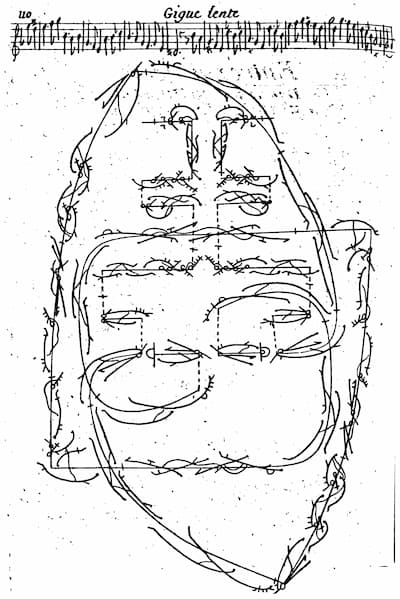

In Feuillet’s and Pécourt’s early 18th century collection, they present the choreography as used in various ballets, mostly by Lully. Here is the middle section of a slow gigue. The two dances start in the center and then move in opposite directions, starting with a large irregularly shaped circling around each other.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Men’s and Women’s steps for the Gigue Lente, 1704

The Italian giga, although it sounded faster than the French gigue, actually had a slower harmonic rhythm. It also didn’t have the irregular phrases of the French model.

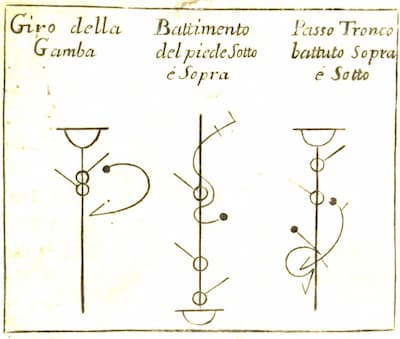

When dances were the social entertainment, there was an enormous business in traveling dancing masters teaching the latest steps, and books published to show how to perform them. This early 18th-century book shows your foot positions, where you turn your leg, where you beat your foot, and bend your knee while your leg is in the air.

Dufort: Trattato el ballo nobile, 1728

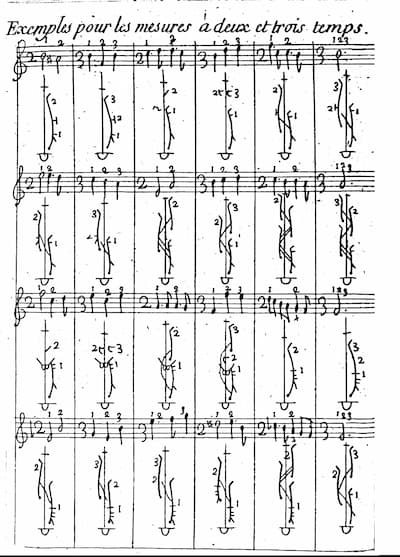

In this more elaborate image from Raoul-Auger Feuillet and Guillaume Louis Pécourt’s 1704 book Recüeil de dances, they give examples of foot movements based on the musical rhythm.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances, 1704

By the 18th century, the dancing manuals were decrying the introduction of ballet steps onto the dance floor. One 1818 manual asks that dancers be more aware of what they are doing: ‘The chaste minuet is banished; and, in place of dignity and grace, we behold strange wheelings upon one leg, stretching out the other till our eye meets the garter; and a variety of endless contortions, fitter for the zenana of an eastern satrap, or the gardens of Mahomet, than the ball-room of an Englishwoman of quality and virtue.’ In 1875, an American dance manual starts out with the plain declaration that ‘The dance of society, as at present practiced, is essentially different from that of the theatre, and it is proper that it should be so. The former, consisting of movements at once easy, natural, modest and graceful, affords an exercise sufficiently agreeable to render it conducive to health and pleasure. The latter…requires in its classic poses, poetical movement, and almost supernatural strength and agility, too much study and strain…to admit of its performance off the stage…’

As these dance works entered the instrumental repertoire and took to the concert stage versus the dance floor, they became disassociated from their dances – their tempos changed so as to be undanceable and it is the contrast between movements that become the focus: duple or triple meter? Fast or slow tempo? In the next parts we will look at other dance movements, some from the Baroque and others more familiar from the Classical and Romantic repertoire.

The Most Memorable Composer Christmases: Mahler, Rachmaninoff, and More

by Emily E. Hogsta

The great composers also experienced a wide variety of Christmas celebrations. Today, we’re looking at five memorable Christmases from the lives of five great composers. (Read Part 1 here: The Most Memorable Composer Christmases: Chopin, Schumann, and More)

Mahler’s Devastating Breakup – 1884

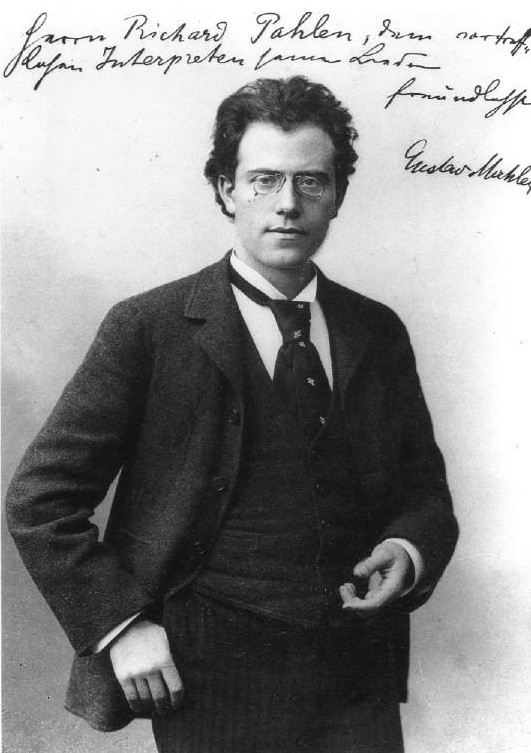

Gustav Mahler

In mid-1883, 23-year-old Gustav Mahler took a job conducting opera at the Königliches Theater in Kassel, Germany.

While there, he began working with 25-year-old coloratura soprano Johanna Richter and fell in love with her. It was his first intense love affair.

We are not sure if Richter reciprocated Mahler’s feelings quite as intensely; only one letter from her survives.

In 1884, he began composing for her, writing lyrics based on folksongs and setting them to music. He called the resulting song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, or Songs of a Wayfarer. His December 1884 was absorbed by the project.

Despite his passion for Richter, the couple was ultimately doomed.

He spent New Year’s Eve of 1884 with her and wrote to a friend about the experience:

I spent yesterday evening alone with her, both of us silently awaiting the arrival of the new year.

Her thoughts did not linger over the present, and when the clock struck midnight, and tears gushed from her eyes, I felt terrible that I, I was not allowed to dry them.

She went into the adjacent room and stood for a moment in silence at the window, and when she returned, silently weeping, a sense of inexpressible anguish had arisen between us like an everlasting partition wall, and there was nothing I could do but press her hand and leave.

As I came outside, the bells were ringing, and the solemn chorale could be heard from the tower.

Although the relationship didn’t work out, Mahler did reuse ideas from Songs of a Wayfarer in his first symphony, which he composed between 1887 and 1888. He wasn’t about to let his holiday heartbreak go to waste!

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel Is Disappointed by the Christmas Singing of Papal Singers – 1839

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny Mendelssohn were two of the most talented child prodigies in the history of music. They remained close for their entire lives.

Felix, however, was encouraged to pursue a musical career, while Fanny’s musical accomplishments were viewed as mere feminine adornments. (Luckily, her husband understood her talent and encouraged her music-making.)

Long story short, Felix got support that she never did, and in 1830, when Fanny was 24, and Felix was 21, the family sent him on a ten-month trip to Italy…without Fanny. The trip was formative, and Fanny was fascinated by the stories of his travels.

Happily, Fanny got to go eventually. Between 1839 and 1840, Fanny, her husband, and her baby son Sebastian took their own trip to Italy, following in Felix’s footsteps.

On 1 January 1840, she wrote to her brother, sharing some observations about musical life in Rome:

We’re enjoying a pleasant life here. We have a comfortable, sunny apartment and thus far have enjoyed the nicest weather almost continuously. And since we’re in no particular hurry, we’ve been viewing the attractions of Rome at our leisure, little by little.

It’s only in the realm of music, however, that I haven’t experienced anything edifying since I’ve been in Italy.

I heard the Papal singers 3 times – once in the Sistine Chapel on the first Sunday in Advent, once in the same place on Christmas Eve, and once in St. Peter’s basilica on Christmas day – and have to report that I was astounded that the performances were far from perfect.

Right now, they seem to lack good voices and sing completely out of tune…

One can’t part with one’s trained conceptions so easily.

Church music in Germany, performed with a chorus consisting of a few hundred singers and a suitably large orchestra, assaults both the ear and the memory in such a way that, in comparison, the pair of singers here seemed quite thin in the wide expanses of St. Peter’s.

With respect to the music, a few passages stood out as particularly beautiful. On Christmas Eve, for instance, after the parts had dragged on separately for a long time, there was a lively, 4-part fugal passage in A-minor that was very nice.

I later discovered that it began precisely at the moment when the Pope entered the chapel, and I didn’t know it at the time because women, unfortunately, are placed in a section behind a grille from which they cannot see anything.

This section is far away, and in addition, the air is darkened by the smoke from candles and incense.

On the other hand, I could at least occasionally see the officials on Christmas day in St. Peter’s very well, and found them quite splendid and amusing.

We naturally had a Christmas tree, because of Sebastian, and constructed it out of cypress, myrtle, and orange branches. The branches were very lovely, but it wasn’t the best-looking tree, and Sebastian and I attempted to outdo each other the entire day in feeling homesick.

Johannes Brahms Surprises Clara Schumann – 1865

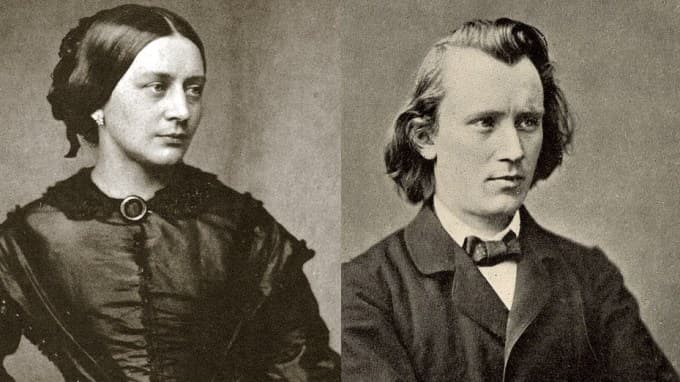

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms and Robert Schumann’s wife, virtuoso pianist Clara Schumann, stayed close friends until the end of their lives.

They never had a traditional romance, but they loved each other deeply, and over their decades-long relationship, Brahms spent many holidays with Clara and her children.

At Christmas 1865, Johannes was 32, and Clara was 46. Both had busy performing careers that necessitated frequent travel, and Clara assumed that she wouldn’t be seeing Johannes for the holidays.

She sent him a traveling bag as a Christmas gift. With the gift, she included a letter talking about her daughter Julie, who had recently been ill.

She wrote, “Thank heaven we have fairly good news of Julie. She has got over the danger of typhoid, but it will be a long time before she has completely recovered.”

The family was worried about Julie’s health, and they didn’t even bother lighting candles on the tree that year.

But then the door opened – and Brahms appeared! He had made a seven-hour journey to Düsseldorf to surprise the family and check in on Julie himself.

Clara wrote in her diary that she was “very pleased and excited.”

Read our article about Christmas with Brahms.

Rachmaninoff Flees Russia – 1917

Kubey-Rembrandt Studios: Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1921

The Russian Revolution began in February 1917, leading to Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication in March and a provisional government taking power.

During that year’s October Revolution, a Bolshevik insurrection overthrew the provisional government. Once the Bolsheviks took power, a broader civil war broke out.

The conflict impacted Rachmaninoff’s life deeply. In the spring of 1917, he returned from touring to find that his estate had been seized by the Social Revolutionary Party. He departed, disgusted, and vowed never to return.

He and his family moved to Moscow. As tensions rose throughout the fall, he made edits to his first piano concerto with the sound of bullets flying in the background.

During this tense time, he received an invitation to give a series of recitals in Scandinavia. He accepted because it would give him and his family an excuse to flee the country.

On 22 December 1917, the Rachmaninoffs got on a train in St. Petersburg, crowded with terrified passengers who feared arrest. Fortunately, the officials who met them were kind.

The following day, they arrived at the Finnish border. To get across it, Rachmaninoff, his wife, and two daughters had to travel in an open peasant sleigh during a blizzard.

They arrived in Stockholm on Christmas Eve. Exhausted, the family stayed in their hotel.

After escaping Russia, Rachmaninoff would go on to a celebrated performing career, but he would compose less and less. Later in his life, he would remark, “I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also.”

Leonard Bernstein Conducts the Historic Berlin Wall Concert – 1989

Leonard Bernstein

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall was taken down, signaling the demise of the so-called Iron Curtain that had hung across Europe for a generation.

Conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein helped to organise a performance at the present-day Konzerthaus Berlin. This venue had been burned out during World War II but was reconstructed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, opening just a few years before this concert.

Musicians from all around the world participated, including men and women from Leningrad, Dresden, New York, London, and Paris.

Together on Christmas Day 1989, they performed a concert celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Bernstein programmed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and changed the Ode to Joy to the Ode to Freedom.

It was broadcast all over the world and became one of the most famous orchestral performances of the twentieth century, seen live by around 100 million viewers. How’s that for a memorable Christmas?