It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, November 3, 2025

Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2, Adagio. Yuja Wang Breathtaking...

Sunday, June 22, 2025

Ten Greatest Women Pianists of All Time

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

So many women have done so that it’s impossible to make an objective list of the ten greatest women pianists of all time.

However, there’s nothing keeping music lovers from creating their own subjective lists.

Here’s one such subjective list, featuring some of the greatest women pianists who were born between 1751 and 1987.

Let us know who would be on your list!

Maria Anna Mozart (1751–1829)

Maria Anna Mozart, nicknamed Nannerl during her childhood, was Wolfgang Amadeus’s older sister.

Their father, Leopold, began teaching her keyboard when she was seven years old. She immediately proved to be a prodigy and was a full-blown virtuoso by eleven.

Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart by Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni © madamegilflurt.com

When the Mozart family first began touring Europe, Nannerl was initially the bigger draw and was often given top billing over her brother.

During her career, she played for aristocrats and royal families in Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, and Britain.

After she turned eighteen and became of marriageable age, her family withdrew her from the concert platform. She was forced to watch from the sidelines as Wolfgang continued his travels and musical education in Italy without her.

She married a widowed magistrate in 1784 and moved to a home thirty kilometres from the family hometown of Salzburg. She had three children of her own and also helped to raise her husband’s five children from his previous marriages.

She continued to play the piano for multiple hours a day. Even after her husband died, she continued playing and teaching.

Maria Szymanowska (1789–1831)

Maria Szymanowska was born to a wealthy family in Warsaw in 1789.

We don’t know for sure how she began her musical life, but it seems likely that she studied with Frédéric Chopin’s teacher, Józef Elsner. She gave her first public recitals in 1810, the year of Chopin’s birth.

She also married in 1810 to a man named Józef Szymanowski. They would have three children together, including a set of twins. They separated in 1820.

Maria Szymanowska

Szymanowska made several tours during her marriage, but her touring activities ramped up in the 1820s. During that decade alone, she appeared in Germany, France, Britain, Holland, Belgium, Italy, and Russia.

She composed works for piano that were deeply influenced by her Polish roots. (Some historians have argued that they influenced a young Chopin.) She became a great favorite in musical salons, and many composers dedicated works to her, including Beethoven.

During her visit to St. Petersburg, she was named First Pianist to the Russian Imperial Court. In 1828, she decided to settle in St. Petersburg, but she died in the 1831 cholera epidemic, cutting short a major career.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819–1896)

Clara Wieck was born in 1819 to piano teacher and music shop owner Friedrich Wieck. As soon as Clara was born, he decided he wanted to mold her into a great piano virtuoso.

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1850

Years of intense study followed. True to Friedrich’s prophecy, Clara proved to be one of the most talented pianists of her generation, male or female.

Her life – and classical music – was changed forever when, in the 1830s, she fell in love with her father’s student Robert Schumann.

Her father protested against the marriage for a variety of reasons, but as soon as she was legally able to, they were married in 1840.

The Schumanns had eight children together, but not even motherhood could keep Clara from continuing her performing career.

After Robert’s mental health collapsed and he died in 1856, Clara continued performing, both out of economic necessity and as a kind of therapy to guide her through her grief.

Throughout her life, she advocated for works by her husband, Chopin, Beethoven, and, perhaps most importantly, Brahms, among many others.

She also reshaped the role of the modern virtuoso, helping to popularize the modern recital format and playing from memory onstage.

Teresa Carreño (1853–1917)

Teresa Carreño was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1853.

When she was nine, the family emigrated to New York City, where she began her concert career in earnest. When she was ten, she played for Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

She embarked on her first European tour in 1866. She spent years there, befriending many of the giants of the art: Rossini, Gounod, and Liszt, among others.

Teresa Carreño

In 1873, she married virtuoso violinist Emile Sauret and the following year gave birth to their daughter, Emelita. Sadly, the marriage didn’t last long, and Carreño and Sauret split up.

She would go on to remarry three more times, and have four more children (one of them, Teresita, would become a concert pianist in her own right). Her turbulent love life would become part of her legend.

During the 1870s and 1880s, she spent most of her time touring America, with a couple of trips to Venezuela sprinkled in. In 1889, she returned to Europe to great success. A final large tour to America took place in the 1890s. She died in 1917 in New York City.

Conductor Henry Wood memorably wrote about her:

It is difficult to express adequately what all musicians felt about this great woman who looked like a queen among pianists – and played like a goddess. The instant she walked onto the platform her steady dignity held her audience who watched with riveted attention while she arranged the long train she habitually wore.

Dame Myra Hess (1890–1965)

Myra Hess was born in London in 1890 and began her piano studies at the age of five. She entered the Royal Academy of Music when she was twelve.

She made her orchestral debut when she was seventeen, playing the fourth Beethoven piano concerto under conductor Thomas Beecham.

Myra Hess

Her career plateaued in the late 1910s due to World War I, but she returned to touring as soon as it was over.

However, arguably her greatest artistic triumph happened during World War II, when she organized nearly seventeen hundred concerts over the course of the conflict, playing in 150.

Concert halls had to be blacked out at night to avoid bombing by Nazi planes. So Hess organized lunchtime daytime concerts at the National Gallery in London.

If bombing prevented a performance from taking place, the series would be relocated temporarily, before returning to the gallery.

Over 800,000 people attended her lunchtime concerts, making it one of the most effective morale boosters of the war.

She suffered from a stroke in 1961 and died from a heart attack in 1965.

Alicia de Larrocha (1923–2009)

Alicia de Larrocha was born in 1923 into a family of pianists in Barcelona, Spain. She began studying piano when she was three with teacher Frank Marshall, and gave her first performance when she was five. Marshall would remain her only teacher after the age of three.

She began touring internationally in her mid-twenties and enjoyed a vibrant performing career for decades thereafter.

Alicia de Larrocha

De Larrocha was especially celebrated for her advocacy of Spanish composers like Granados, de Falla, and Albéniz.

But her expertise didn’t stop there: her performances of the Germanic composers like Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, and Mozart were also highly praised.

She even recorded Liszt, despite the fact that she was less than five feet tall and her hands were small.

She recorded extensively throughout her career and won four Grammy awards between 1975 and 1992.

She retired in 2003 after seventy-five years of public performances. She died in 2009, at the age of 86.

Martha Argerich (1941–)

Martha Argerich was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1941, to a Spanish-Russian family. She began learning the piano at the age of three and gave her debut concert at the age of eight.

In 1955, when Martha was fourteen, the Argerich family moved to Vienna. She began studying there with iconoclast pianist Friedrich Gulda. Two years later, she won both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition.

Martha Argerich with The Philadelphia Orchestra, 2008 © carnegiehall.org

Despite her success, she found herself in a musical crisis, and she quit playing for three years. Thankfully, she changed her mind, returning to music, and she won the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1965, when she was twenty-four. It was the kickoff to a decades-long performing career.

In the 1980s, Argerich revealed that performing solo recitals made her feel lonely, so since that time, she has focused on repertoire that includes other musicians, such as concertos and chamber music.

In addition to her storied career as a performing artist, she has worked as a teacher and mentor. She is the president of the International Piano Academy Lake Como and has appeared regularly on competition juries.

As of 2019, at the age of 78, she was still performing the Tchaikovsky piano concerto. As one critic wrote in 2016, “Her playing is still as dazzling, as frighteningly precise, as it has always been; her ability to spin gossamer threads of melody as matchless as ever.”

Mitsuko Uchida (1948–)

Mitsuko Uchida was born outside of Tokyo in 1948. Her family moved to Vienna when she was twelve, and she began studying at the Vienna Academy of Music. She made her recital debut in Vienna at fourteen.

Mitsuko Uchida © Geoffroy Schied

In 1970, when she was twenty-two, she won the second prize in the International Chopin Piano Competition. The prize marked the beginning of a decades-long career.

She has become especially renowned as an interpreter of Mozart. She has recorded all of Mozart’s piano sonatas and concertos, a staggering accomplishment.

If that wasn’t enough, she decided to re-record the Mozart concertos, while also conducting. In 2011, she won a Grammy award for the first record in the series.

She is also famous for being the artistic director at the prestigious Marlboro Music School and Festival, a position she has held since 1999. (She currently shares the position with fellow pianist Jonathan Biss.)

Even today, in her mid-seventies, she is still performing and recording.

Hélène Grimaud (1969–)

Hélène Grimaud was born in 1969 in Aix-en-Provence, France. She began playing the piano at seven.

She began studying at the Paris Conservatoire in 1982 when she was thirteen, and gave her recital debut in Tokyo five years later.

Hélène Grimaud

She gave important debuts with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1995 and New York Philharmonic in 1999.

In 2002, she signed with the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label, and in the two decades since has released a number of well-received recordings.

She is noted for her wide interests outside of music. She is deeply involved with multiple wildlife conservation efforts and is also a member of Musicians for Human Rights.

She has also written or co-written four books. Her first, Variations sauvages (Wild Variations), published in 2003, is an autobiography. The cover features a photo of her being greeted by three wolves she has met through her wildlife conservation work.

Yuja Wang (1987–)

Yuja Wang was born to a musical family in Beijing in 1987. She began studying piano at the age of six and enrolled at the Beijing Conservatory when she was seven.

Yuja Wang, 2021

When she was fifteen, she moved to Philadelphia to study at the storied Curtis Institute of Music. She studied there with legendary pianist Gary Graffman for five years. We wrote an article about their teacher-student relationship.

She made her European debut in 2003, at the age of sixteen. Her North American debut came two years later.

Her breakthrough performance is widely considered to have happened in March 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich at the Boston Symphony, playing Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto.

Since then, she has been in constant demand at the best orchestras and recital venues in the world.

In 2023, she made headlines for performing all four Rachmaninoff piano concertos and his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. Ever a fashionista, she changed into a different dress for each concerto. She even played an encore!

In 2012, Joshua Kosman of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Yuja Wang is “quite simply, the most dazzlingly, uncannily gifted pianist in the concert world today, and there’s nothing left to do but sit back, listen and marvel at her artistry.”

The words were prophetic. The rich tradition of women pianists – as well as the broader tradition of pianism generally – is in good hands!

Friday, December 13, 2024

By Janet Horvath, Interlude

The ganjingworld investigation began with statistics: Yuja Wang has played so far, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2, thirty-five times, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 1, fourteen times, Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 4, twenty-one times, Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini thirty-one times, and Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3, a total of 72 times.

No one had ever attempted playing all of Rachmaninoff’s five works for piano solo with the orchestra before. Who else would have the stamina to do it? It’s akin to winning a gold medal in the Olympics or climbing Mount Everest.

In planning the program, Yuja decided the 3rd Piano Concerto had to conclude the program as it is the epitome of emotion, drama, and physicality. Who can play anything after that?

Unsurprisingly, Wang’s virtuosity and musicality were riveting from beginning to end. Wang also amazed the audience with a different outfit for each concerto while keeping track of the tracking device.

© Carnegie Hall

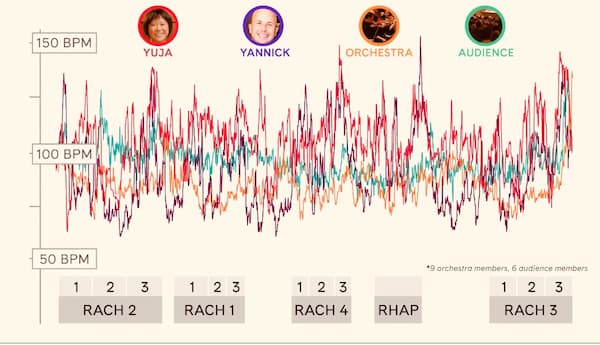

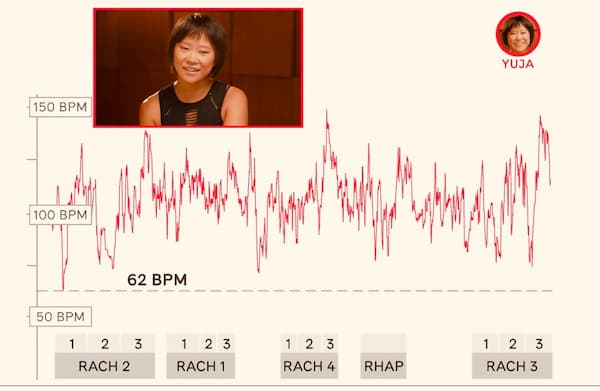

When the results were revealed to Wang, it was uncanny that she could look at the graph and identify exactly where she was in the music just by looking at the peaks and the valleys of her heartbeats.

The highest peaks, of course, occur where the music is physically or psychologically difficult. As a benchmark note, resting beats per minute is approximately 62 BPM. During the finale of the 2nd Concerto, her heart rate reached 139 BPM, predictably where there are more notes, and it’s faster and louder. During the finale of the 3rd Concerto, she surpassed that number at 146 BPM. But the highest level reached 149 BPM— 233% more than resting—was during the finale of the 4th Concerto.

The interesting thing is that Wang’s heart rate didn’t always consistently go up when it was loud and fast or just in the finales. In fact, the 3rd Concerto, despite being the longest and most difficult concerto, on average, indicated the lowest BPM rates. Wang thinks there are two reasons for this slower heart rate. Spiritually, the piece has a calming effect on her. Technically, as an elite and superbly skilled pianist, she’s able to save her energy when needed during the performance. Her heart rate is affected by how economical her movements are.

There is a third possibility to consider. Perhaps the reason her heartbeats were higher in the first and fourth concertos is that Wang has had the least experience performing these works. If she was more keyed up, it certainly would affect one’s heart rate.

Another statistic amused Yuja Wang. The numbers indicated how much harder she worked than the conductor. She: 2,427 calories burned and 20,275 steps taken; He: 1,645 calories burned and 15,079 steps taken.

Vindicated! We musicians know this! But Yannick actually recorded the highest peak, higher than any of Wang’s uppermost BPMs, when he reached 153 BPM in the final variations #19-24 of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. It is, of course, a very exciting ending, and it’s strenuous to marshal all the musicians for this mighty climax, as it is for us to play it.

Throughout his career, Nézet-Seguin has sought to bring people in sync with his music-making. He was astonished when he saw this reflected on the graph. There is an amazing synchronicity when comparing the heartbeats of the soloist and the conductor. Yuja and Yannick were musically and physically on the same wavelength throughout. But even more impressive, even during Wang’s cadenzas, when the orchestra and the conductor were “at rest,” their heartbeats rose in sync with the soloist’s playing and emotion. Whenever the music became more emotionally intense, the constant interdependence between all the musicians on stage, even when they weren’t playing, was notable. The phenomenon could be seen in the tracking devices of audience members as well. Their heartbeats went up, too, during the emotionally moving sections.

Does this occur in other settings? Choir music and song have permeated civilisations throughout different cultures and religions. In a 2013 study, it was documented that when choirs sing, their heartbeats become synchronized, beating as one. An article in NPR and the BBC World Service in July of 2013 reported that researchers of the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden studied the heart rates of a high school choir in a variety of choral works. They published their results in Frontiers in Neuroscience. Singers must exhale and inhale in a coordinated fashion. The findings showed that singing in a choir calmed the singer’s heart rate, especially when they were singing in unison, and within a few moments, each person’s heartbeat became synchronised. Somehow, the singers’ collective consciousness is connected to each other. Their controlled breathing, as we’ve seen in yoga and in other meditational practices, had a quietening effect.

Listen to The VocalEssence Ensemble Singers conducted by Philip Brunelle perform “The Day is Done” by Minnesota composer Stephen Paulus to a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “And the night shall be filled with music, And the cares, that infest the day, Shall be banished like restless feelings, That silently steal away.”

I can’t help respiring, sighing with them.

Stephen Paulus: The Day in Done

Choirs breathe together, but so do wind and brass musicians in a band, ensemble, or orchestra—to make a phrase, to play seamlessly, and to express the musical lines homogeneously. Many audience members may not know that string players must also breathe together, especially during chamber music performances when we don’t have a conductor. The sniff at the beginning of a piece, in addition to body language, will lead colleagues, much like a conductor’s upbeat, and the rate of the sniff indicates many things—when to play, the type of entrance, the rhythm, the meter, the style. Breathing helps us stay together and to feel the music as one.

The Yuja Wang Rachmaninoff Heartbeat Study was more than an amusing experiment. Dr. Bjorn Vickhoff concludes, “We speculate that it is possible singing could also be beneficial.” Performing and listening to music is good for us and is a positive experience which can synchronise our heartbeats. Unlike many other activities, music can bring people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds together, in sync, in harmony, despite wide-ranging experiences with music.

Here is the video of the entire study courtesy of Yuja Wang, and Carnegie Hall, director Joe Sabia, producer Greg T. Gordon, Images Carnegie Hall Rose Archives, Cartoon Jeffrey Curnow.

Thursday, November 14, 2024

Classical music is far from boring

"Classical music is far from boring - it has all the blood, energy, the sinister dark side, rhythm that rock music has, and all the refined, subtle sensuality that one can ask for."- Yuja Wang

Wednesday, July 24, 2024

Yuja Wang: Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor Op. 21 [HD]

Wednesday, July 17, 2024

Yuja Wang - Ravel: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Tuesday, July 9, 2024

Saturday, May 18, 2024

A Recital with A Difference: Yuja Wang’s The Vienna Recital

By Maureen Buja, Interlude

Yuja Wang

In her recent recording The Vienna Recital, pianist Yuja Wang turns the original idea of a recital on its head. She does what you expect, with a bit of Beethoven to cover the Classical period, a bit of Brahms for the Romantic period, and a bit of Scriabin for the 20th century but then there’s music by Albéniz, Glass, Scriabin, and Kapustin for some jazz preludes. Delicacy of touch and contrast in styles seem to be the driving force for the assemblage of pieces here and there are some brilliant choices. The juxtaposition of Arturo Márquez’s Danzón No. 2, one of the best-known modern Mexican orchestral pieces, here transcribed for solo piano, with one of Brahms’ Intermezzi, op. 117, seems to move Brahms into the same space where you were just dancing to Márquez’s music.

The selection of the music takes you over a range of centuries – from Gluck to the modern day – and presenting the works in a non-chronological order makes you rethink the details of the works, from harmony to rhythm.

It’s difficult to pick one track that shows how wonderful this album is, but we’ll go with one of the Ligeti Études. Number 13 from Book 2, The Devil’s Staircase, is a toccata of unending movement.

György Ligeti: Book 2, No. 13 – L’escalier du diable

Chinese pianist Yuja Wang (b. 1987) started her studies at age 7 at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing before entering the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia at age 15. Even before her graduation in 2008, she had come to the world’s attention when she replaced Martha Argerich in a series of concerts with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 2007. Her performing triumphs continued, today making her one of the leading pianists in the world.

If your idea of a recital is something to be endured with a few gems as a reward, then this recording will change your mind completely – it’s both constantly challenging to the pianist and constantly rewarding to the listener.

YuJa Wang: The Vienna Recital

Deutsche Grammophon 00028948645671

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter