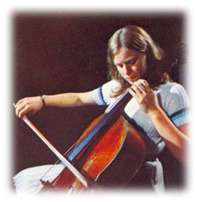

Jacqueline Mary du Pré (1945-1987) is arguably one of the most gifted cellists of our time. She is particularly remembered for her legendary debut performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor (one of the favourite cello concertos of all time), which she performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in 1962 under Rudolf Schwarz.

Jacqueline Mary du Pré (1945-1987) is arguably one of the most gifted cellists of our time. She is particularly remembered for her legendary debut performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor (one of the favourite cello concertos of all time), which she performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in 1962 under Rudolf Schwarz.

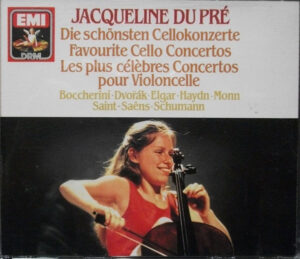

Jacqueline du Pré’s performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto was regarded so highly that she returned three years in succession to perform this favourite work, and further recorded it for EMI in 1965 (album title “Jacqueline Du Pré – Favourite Cello Concertos”). Considered the finest interpreter of Elgar’s Cello Concerto, her work instantly became known as the benchmark reference which made her an international star. On 14 May 1965, she performed at Carnegie Hall for her United States debut.

Sadly, what began as a promising international career was cut short by a nervous system disease called multiple sclerosis, and she died in 1987 at the age of 42.

Du Pré’s Childhood

Du Pré was born in Oxford into a middle-class family. At the young age of four, she heard the sound of the cello on the radio for the first time and asked her mother for “one of those”. Her mother immediately noticed Du Pré’s fascination with the instrument and gave her her first music lessons, and by five she was enrolled into the London Violoncello School.

In 1956, Du Pré became the youngest recipient of the Suggia Gift Award, a scholarship established by the renowned Portuguese cellist Guilhermina Suggia. At just age 11, she continues to hold the title as the youngest recipient till this day. The award enabled her to further her studies at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. She also began winning many music competitions that further confirmed her talent and ability in the instrument.

As a Suggia awardee, Du Pré was required to practice the cello at least four hours a day, an obligation that cut her off from normal school activities and relationships. However, this allowed her to study under renowned cellist William Pleeth, a child prodigy himself.

Pleeth’s influence in Du Pré’s life was unquestionable. She called him “my Cello Daddy”, while Pleeth explained that teaching her was “like hitting a ball against a wall. The harder you hit it, the harder it would return. I could see the potential quite strongly on the first day. As the next few lessons went on, it just sort of unfolded itself like a flower, so that you knew that everything was possible.“

Studying with Casals and Tortelier

After becoming the youngest performer to ever win the Queen’s prize, Du Pré continued her studies under world-famous cellists Pablo Casals in Switzerland, Paul Tortelier in Paris and Mstislav Rostropovich in Russia. An anonymous benefactor bought her the beautiful 1673 Stradivarius cello in preparation for her professional debut. Rostropovich, who was so impressed with the young cellist, declared her “the only cellist of the younger generation that could equal and overtake his own“.

In 1966, Du Pré was invited to perform the Brahms F major Sonata with Israeli conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim. The two quickly fell in love and married in May the next year. TIME magazine wrote, “Thus began one of the most remarkable relationships, personal as well as professional, that music has known since the days of Clara and Robert Schumann.” Their marriage thrilled listeners around the world, and marked a triumphant period for both. Together they toured throughout North America and Europe, and recorded what became part of Du Pré’s legacy of recordings.

In 1966, Du Pré was invited to perform the Brahms F major Sonata with Israeli conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim. The two quickly fell in love and married in May the next year. TIME magazine wrote, “Thus began one of the most remarkable relationships, personal as well as professional, that music has known since the days of Clara and Robert Schumann.” Their marriage thrilled listeners around the world, and marked a triumphant period for both. Together they toured throughout North America and Europe, and recorded what became part of Du Pré’s legacy of recordings.

During the two years after the Elgar performance, she sometimes noticed numbness in her fingers. She could not pinpoint the exact time when it started, but she did take a break from the exhaustion of touring and performing in spring 1971 to move in with her sister Hilary in Ashmansworth, Hampshire.

Jacqueline Du Pré – Favourite Cello Concertos album © Discogs

When she resumed concert appearances in 1972, the numbness in her hands grew steadily worse. Her doctors could not explain the condition, but told her it was caused by stress. At a rehearsal for the Brahms Double Concerto in 1973 she needed help to open her cello case and said that she could not feel the strings with her fingers. She had to rely on her eyes to tell where her fingers were placed on the instrument.

Du Pré told Leonard Bernstein that she was unable to play. “Don’t be such a goose“, he told her. “You’re just nervous.” Although she managed three of the concerts, the third ended up as a disaster. That marked her last appearance as a cellist.

As a result, Bernstein took her to a doctor in New York, but neither could he find anything wrong with her. Du Pré began to wonder if she was going mad. Only after several tests in London two years later was she finally diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. The music world was stunned by the news that she might never play again.

Tributes soon poured in, including an Order of the British Empire (OBE) amongst other honorary degrees. Confined to a wheelchair now, Du Pré continued to contribute to the music world by conducting master classes at the Guildhall School and even conducted several of them on television. However, her health continued to decline. She died in 1987, at the age of forty-two.

In the words of her friend Christopher Nupen, “The loss is still touching the hearts of people all over the world, because this great cellist had ways of reaching the heart that are given to very, very few.“

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple Sclerosis is a nervous system disease that affects communication between the brain and the spinal cord. The inflammatory disease causes the body’s own defense system to attack the myelin sheath, the material that protects the nerve cells around the axons of the brain and spinal cord.

When myelin is lost, the axons can no longer effectively conduct signals. Consequently, the nerve impulses are distorted and interrupted, causing the patient to suffer almost any neurological symptoms including numbness, muscle weakness, difficulty in moving, coordination problems, amongst others.

Multiple Sclerosis usually occurs in young adults and is more common in women than men. Despite the advances in medical science and our knowledge about the disease process, little is known about the cause of the disease. The disease is usually mild but some people may lose the ability to write, speak or walk.

Despite her early departure, Du Pré left us a wonderful legacy of recordings, though her admirers may complain they were not enough. Nevertheless, Du Pré will be remembered for the elegance and ferocity that transcends in her music.

“There is plenty of strength to her playing, and a good measure of romanticism without the romantic string mannerisms of portamento (sliding from note to note) and a fast wide vibrato. She can produce a mellow sound of unusual size and clearly was born to play the cello,” wrote Harold C. Schonberg in The New York Times after her 1967 concert.

Elgar – his music Cello Concerto. (n.d.). Retrieved August 22, 2011, from Jacqueline du Pré — The concerto’s consummate interpreter?: http://www.elgar.org/3cello-b.htm

Muelle, M. (n.d.). Jacqueline Du Pré. Retrieved August 22, 2011, from Jacqueline Du Pré: http://www.jacquelinedupre.net/jdupre/whoisjdp.htm

New York Times. (1987, October 20). Jacqueline du Pre, Noted Cellist, Is Dead at 42. Retrieved August 22, 2011, from New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/1987/10/20/obituaries/jacqueline-du-pre-noted-cellist-is-dead-at-42.html

Zukerman, E. (1999, April 25). Heartstrings. Retrieved August 23, 2011, from Multi-sclerosis: http://www.mult-sclerosis.org/news/May1999/BookReviewsduPre.html

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter