It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, July 17, 2024

Yuja Wang - Ravel: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

The Philippine Madrigal Singers celebrate 60 years

SOUNDS FAMILIAR - Baby A. Gil - The Philippine Star

July 18, 2024 | 12:00am

It was in 1963 when future National Artist for Music Andrea Veneracion put together a group of teachers and students from the University of the Philippines College of Music to specifically perform madrigals, a type of secular choral music. As we know now, that little choir grew up into the most popular and most admired group of singers ever assembled in the Philippines.

The Philippine Madrigal Singers or the Madz is now 60 years old. More than 60, in fact, it is currently on a year-long celebration of its six decades of existence.

It was in 1963 when singer and arranger and future National Artist for Music Andrea Veneracion put together a group of teachers and students from the University of the Philippines College of Music to specifically perform madrigals. The madrigal is a type of secular choral music with poetic lyrics performed a cappella and caracterized by beautiful harmonies. It was very popular during the Renaissance period.

As we know now, that little choir grew up into the most popular and most admired group of singers ever assembled in the Philippines. Under the guidance of Veneracion, who was lovingly referred to as Ma’am OA, The Madz enthralled music lovers all over the world with its expressive vocals and masterful handling of harmonies. The group distinguished itself by winning top prizes in the most prestigious choral competitions. Among these were the 1996 International Choral Competition in Tolosa, Spain and the 1997 European Grand Prix for Choral Singing in Tours, France.

The Madz continued to excel with madrigals but had over the years branched out to include, classical, jazz, pop and other types of music in its repertoire. This decision to diversify has resulted in utterly entertaining shows which brings in crowds of music lovers whenever and wherever the choir performs. Take note too that the University of the Philippines is not carried anymore by the Madz. Not that UP has dropped the Madz or vice-versa but because the Philippine Madrigal Singers now belongs to the whole Philippines and not just to UP.

Ma’am OA passed away on July 9, 2013, eight years after she suffered a stroke. As with all National Artists, she is now resting in the Libingan ng mga Bayani. She left the Madz in the hands of the very able choirmaster Mark Anthony Carpio whom she handpicked before she was taken ill. She must be very pleased with her choice, knowing that Carpio continues to steer the group towards victories in European music competitions and in successful international tours. It is Carpio as artistic director who led the Madz, alumni and present members, through their paces for the album that commemorates the past 60 years.

The album is titled “The Sound of Sixty Years, A Homecoming Celebration by The Philippine Madrigal Singers.” This was recorded at the Tanghalang Ignacio Jimenez or the Blackbox Theater of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. The tracks included are a mix of well-loved concert favorites in French, German, Spanish, English and other languages or dialects from the group’s success-filled repertoire.

My favorites are the Tagalog songs. The Madz makes these sound heavenly when performed madrigal style. The cuts are Ang Aking Bituin (O Ilaw) arranged by Lucio San Pedro; Dahil sa Iyo by Miguel Velarde Jr. and Dominador Santiago arranged by Fabian Obispo and the Ilongo lullaby, Ili-Ili Tulog Anay, arranged by Priscilla Magdamo. Then as always the Prayer of St. Francis by Allen Pote, as arranged here by Robert Delgado comes off as most heartfelt and beautiful.

Others included are In These Delightful, Pleasant Groves by Henry Purcell; Chi La Gagliqrda by Baldassare Donato; Il Est Bel Et Bon by Pierre Passereau; Hoy Comamos y Bedamos by Juan del Encina; Wohlauf, Ihr Gaste by Erasmus Widmann Jr.; Mamayog Akun also arranged by Obispo; Iddem-dem Mallida arranged by Elmo Makil; Alleluia by Randall Thompson; L’important C’est la Rose by Louis Amade and Gilbert Becaud and arranged by Magdangal de Leon; and Love is the Answer by Raymond Hannisian.

Dame Mary Beard | My Music: ‘Ancient music is elusive to historians’

Friday, July 12, 2024

The nation’s best-known classicist rediscovered classical music in her thirties, when exploring re‑workings of ancient myth

Iwent to quite a traditional academic school where we were introduced to some of the ‘greatest hits’ of classical music – Saint-Saëns and Handel and that kind of thing – in general music lessons. I learned the basics of music theory and gained an understanding of the nature of classical music which, although I didn’t realise it at the time, stood me in hugely good stead as I got older. Classical music can be quite frightening – there’s a way of talking about it which from the outside seems a bit exclusive – so I feel very grateful that that fear was taken away. During my late teens and twenties I wasn’t remotely interested in the art form, but I’d been equipped with a way of thinking that I could engage with it.

In my thirties I rediscovered an interest in classical music. I met my husband, who was much more interested in the genre than me, so there was a new domestic emphasis for me. That went in parallel with my professional life focusing on the classical past; I became increasingly interested in how myths and stories had been reappropriated, reworked and reinterpreted after antiquity. That was partly in literature, but if you are interested in that kind of reappropriation, you can’t avoid classical music. That’s where some of the most powerful and influential ways of reincorporating myth into modern culture can be found. I got dead interested in Handel’s classical operas and saw in them the living tradition of the classical world.

Ancient stories deal with central problems in human life. It would be an inaccurate cliché to say that they are timeless truths, but they raise timeless questions. For me, there is also the question of ‘Where are the women here?’. One of the things I’ve been very interested in throughout my career is finding what those women were writing, what they were thinking about. It’s not true that there aren’t any women, it’s just that we never noticed them.

I’m now getting my head around more female composers, largely thanks to Nardus Williams [Beard’s collaborator on her upcoming concert, ‘Women’s Stories from the Ancient World’, at Snape Maltings] and I now have the biggest soft spot for Francesca Caccini. She is so wonderfully knowing and manipulative of the tradition she’s working within, and she knows what it is to parody the male autocracy – it’s not full-blown outrage, it’s smart, it’s clever. I think it’s very interesting how women – whether they’re writers, composers or painters – take stereotypes and play with them so elegantly. In my own neck of the woods, for example, one can see in the poems of Sappho, the biggest classical female poet, how she’s exposing the very nature of ‘maleness’ in classical antiquity.

In our upcoming concert, we’re trying to bring to light some of these female voices – from the well-known like Sappho, to people like Caccini, and other Greek poets like Nossis – and look at how they are holding up a mirror to our own preconceptions. If you start putting the women back into the picture, the whole picture gets more interesting, and what we’ve found is that if you put the music together with some of the classical poetry, they really enlighten one another.

Although it’s not written by a woman, Handel’s Semele, is a great example of this. That idea of what it is to be destroyed by the desire for the divine is there in the classical myth, but the multi-sensory performance of Semele in the opera helps me feel that and feel what’s at stake. I never saw the power of the story of Semele (I thought it was a bit of a quaint byway of Greek mythology) until I saw it in the opera. It’s reinvigorated my understanding of that myth forever.

Ancient tragedy was partly set to music, although now we often think of it on the page or with awkward musical interludes (which quite often don’t work), but ancient music is elusive to historians. We know it was hugely important, and we can see people were constantly performing music, but the sound is always just out of our reach. However, I think if you let yourself get immersed in opera, you partly recapture a little of that original experience through the idea that this is not just a world of the spoken word. It gives you license to listen again and to wonder and rethink.

Women’s Stories from the Ancient World, is part of Summer at Snape, August 25

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today

Introducing the August 2024 issue of Gramophone: featuring Joana Mallwitz

Joana Mallwitz: the conductor on recording Kurt Weill symphonies in Berlin | Charles Ives: the composer who captured America’s spirit

This month's cover artist is the conductor Joana Mallwitz, someone who has already attracted a lot of attention as the chief conductor and artistic director of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, and who tells us about her first album for DG, the two symphonies by Kurt Weill.

We also celebrate the 150th anniversary of the American composer Charles Ives, and recommend a range of works to investigate.

As the conductor Leonard Slatkin turns 80, we talk to him about his past achievements and future plans. Elsewhere in the issue, in Icons, we profile the English clarinettist Thea King, who was renowned for championing the 19th-century repertoire of her instrument.

In Classics Reconsidered, we reassess Charles Mackerras’s 1966 recording of Handel’s Messiah, a pioneering account.

Our Collection this month traces the history on record of the most lyrically sublime of Beethoven’s late piano sonatas, Op 110, and recommends some essential listening.

The Contemporary Composer focus introduces the wide-ranging work of the British composer Robert Saxton and suggest entry points for exploring his music, while in Musician & the Score Manfred Honeck talks about his approach to conducting Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony.

Finally, in My Music, we meet classicist Dame Mary Beard to find out about the place of classical music in her life.

Plus, as always, our world-leading critics review the latest classical music releases – with the best being crowned ‘Editor’s Choice’.

Tuesday, July 16, 2024

Gracie Abrams - Close To You (Jimmy Kimmel Live! 2024)

Monday, July 15, 2024

Yuja Wang - Prokofiev: Piano concerto no.2 op.16

JULIE ANNE SAN JOSE - I BELIEVE I CAN FLY - Julie Sings the Divas

Sunday, July 14, 2024

JULIE ANNE SAN JOSE - ALL BY MYSELF - Julie Sings the Divas

Lindsey Stirling plays “Toccata and Fugue” at Wisconsin State Fair 2023

Saturday, July 13, 2024

Blue Bayou - Paola

Friday, July 12, 2024

Acker BILK : La Mer (Beyond the Sea)

Music 1 songs

16 Year Old Emma Kok sings Dancing On The Stars – André Rieu, Maastricht...

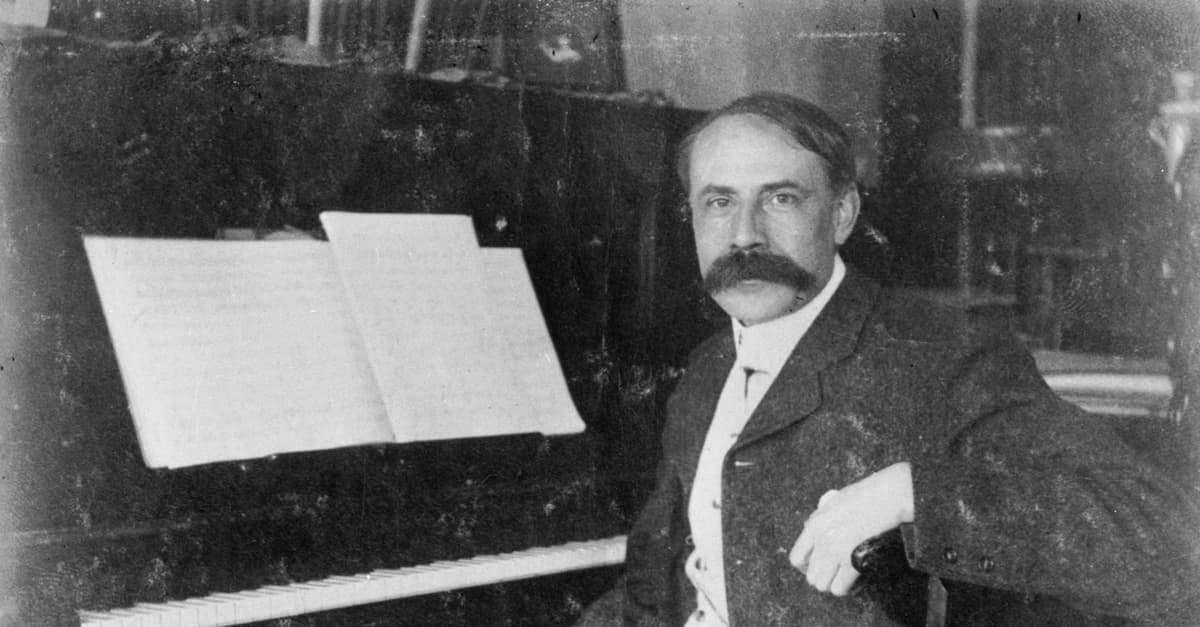

At the Piano With Sir Edward Elgar

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

Edward Elgar

On the other hand, Elgar made his money from lighter and less significant works. He certainly received a steady income from royalties on short pieces composed for publication and sale in the form of sheet music for the home market. And not surprisingly, the most common instrument for home entertainment was for the upright piano. But before we get into the solo piano pieces, here is a delightful Romance for piano and violin, published as Elgar’s Op. 1.

The majority of Elgar’s compositions for solo piano stem from the early part of his career, or the very end of his life. As a child, Elgar was praised for his piano improvisations, but he claimed “that playing the piano gave him no pleasure.” And while he did take some violin lessons, he was certainly a proficient pianist.

Edward Elgar: Chantant

Let’s not get distracted, the majority of Elgar’s works for solo piano were composed specifically with that instrument in mind. Take for example Chantant of 1872, a work written at the age of fifteen in the style of a Mazurka. It features all the rhythmic aspects of that particular dance, with Elgar repeating the principle theme with slight changes of colour. A rather interesting “chorale” serves as a type of interlude with the main theme rushing to a dramatic conclusion.

Edward Elgar: Douce Pensée

A good many of these early pieces were probably composed as musical gifts for friends and relatives. Although similar in style and simply in structure, they all contain a certain gaiety and rhapsodic charm. Just listen to Douce Pensée, composed during a visit to Yorkshire in 1882. Originally, the piece was written as a trio for Elgar, his friend Dr. Buck and his mother.

Elgar met Dr. Charles Buck, a member of the British Medical Association in Worcester in 1882, and that meeting became the start of a life-long friendship. Elgar was invited to Dr. Buck’s house in Giggleswick, Yorkshire, and since the good doctor was a competent amateur cellist and his mother played the piano, Elgar expanded a trio he had started the previous year. He later arranged the trio for solo piano and called it Douce Pensée (Gentle Thought). It eventually also became a piece for violin and piano renamed “Rosemary,” and carried the subtitle “That’s for Remembrance.”

Edward Elgar: Presto

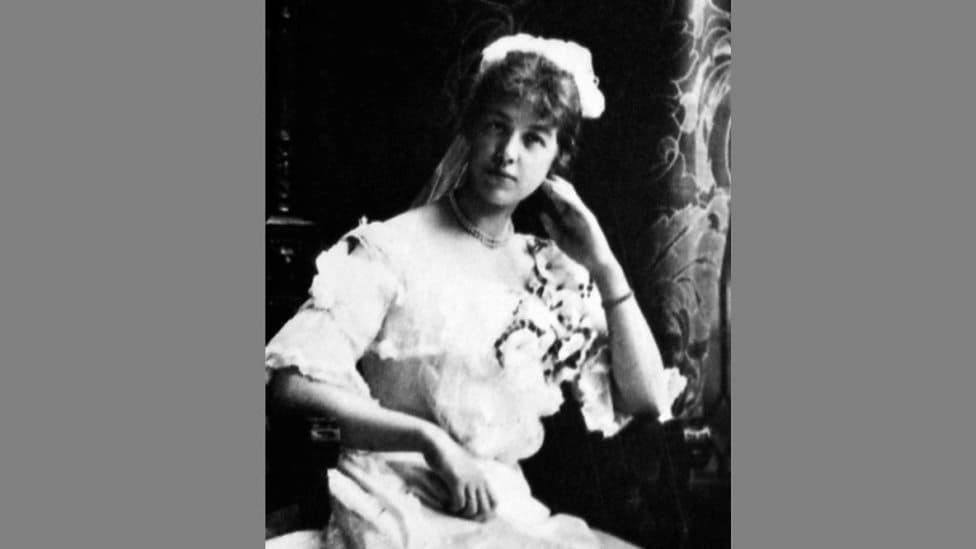

Isabel Fitton

As a birthday present for the twenty-first birthday of Isabel Fitton, Elgar composed a delightful “Presto.” Isabel was the daughter of one of Elgar’s greatest friends, the splendid local pianist Harriet Fitton. Maybe you know that name from another context? Isabel was a viola player, and her name and instrument appears in the sixth Enigma variation dedicated to “Ysobel.” That variation begins with a viola figure that Edward had written for her earlier. The Presto, dating from 1889, however, is all Chopin. After a great opening flourish, we find a short Chopin-like episode, with both sections repeated. Elgar then writes one of his lovely sequential sections, and once the original theme is re-introduced it quietly sings to slightly different harmonies before the piece comes to a quiet close.

Edward Elgar: Sonatina

Elgar in Turkey

Elgar was working on a Sonatina in 1889, originally composed for his 8-year old niece May Grafton. She was the daughter of Elgar’s favourite sister, Pollie. May was actually living in the Elgar household in Plas Gwyn, their Hereford home. She helped to run the household, and she was particularly important to Edward once Alice died. May was a keen photographer, and many of the images of the composer were taken by her.

Only in 1932 did Elgar work on these old piano sketches and he completed the Sonatina, which was published in the same year. The Sonatina is a short work in two movements. According to notes from the Elgar Society, “it contains a sentimental, gently rocking melody that gives way briefly to a tiny contrasting section before reverting to the repeated first section.” The second movement is a more cheerful movement that happily dashes to the finish.

Edward Elgar: Minuet

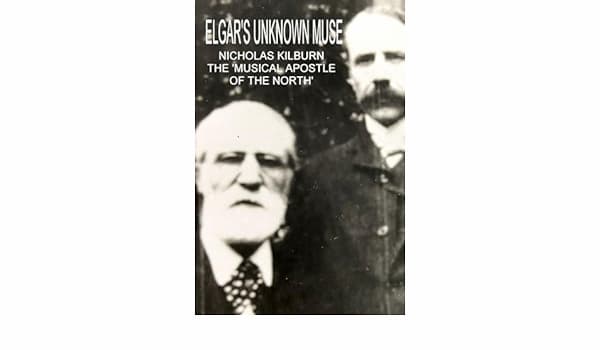

Nicholas Kilburn

Nicholas Kilburn was an iron merchant in Sunderland who was also an amateur conductor and an early champion of Elgar’s work. In fact, he directed all of Elgar’s choral works after 1887 and Elgar referred to him as “The Saint.” Kilburn almost made it into the Enigma Variations, as there is a fragment of a variation that is headed “Kilburn.” In the event, it was Nicholas’ son Paul that the Minuet of 1897 was written for.

This charming piece of music unfold in the form of an arch, as the opening musical turn of phrase keeps returning in the form of a refrain, with a gentle and pastoral melody as the central pillar. Elgar later orchestrated the piece and it was published in its orchestral form in 1897. In the same year, it also appeared as a piano work in “The Dome Magazine,” a publication advertised as “An Illustrated Monthly Magazine and Review of Literature, Music, Architecture and the Graphic Arts.”

Edward Elgar: Concert Allegro, Op. 46

Fanny Davies

The concert pianist Fanny Davies was a student of Clara Schuman and a friend of Johannes Brahms. For many years Elgar had been thinking of writing a piano concerto, but this project never went beyond some sketches. Davies wrote to Elgar in 1901, “I am so disappointed if you can’t let me have just a wee ‘little Elgar’ for my recital on Dec. 2nd … I could learn it very quickly if I had it – and the Concert is not till December 2nd.”

Elgar went to work and produced the Concert Allegro, originally titled “Concerto (without Orchestra) for pianoforte.” Critics were not enthusiastic, and there seems to be the suggestion that Davies played the piece as “anything down to half speed.” Publishers also didn’t want to take on the piece, and many adjustments and amendments were made, including pasting over some original ones. Fanny Davies did continue to perform it, and Richter exclaimed that the work was “as if Bach had married Liszt!” There was some talk of an orchestral arrangement, but the score disappeared and was only rediscovered in 1968.

Edward Elgar: In Smyrna

In the autumn of 1905, Elgar took his friend Frank Schuster on a Mediterranean cruise on the Royal Navy ship HMS Surprise. Elgar went as a guest of the Navy, and he was hosted by Vice-Admiral Beresford. In his diaries Elgar described the journey in great detail, and he was enthused by several places he visited. Among them was the ancient Greek city of Smyrna, currently the Turkish city of Izmir. Elgar noted in his diary, “drove to the Mosque of dancing dervishes … music by five or six people very strange & some of it quite beautiful – incessant drums and cymbals (small) thro’ the quick movements.”

Elgar’s music for “In Smyrna” does not reflect the dervish dances, but rather mirrors an earlier diary entry where he wrote, “Rose late. Very, very hot & sirocco blowing-peculiar feelings of intense heat and wind…” The shimmering qualities are beautifully transferred to the piano and since there are no major climaxes, the work ends quietly. Elgar used some of the materials in his “Crown of India Suite” in 1912.

Edward Elgar: Dream Children, Op. 43

The two movements of “Dream Children” were written in 1902 for either piano or for orchestra. These pieces suggest a strong nostalgia for childhood, as the score is headed by a quotation from Charles Lamb’s Dream-Children, a Reverie. “And while I stood gazing, both the children gradually grew fainter to my view, receding, and still receding till nothing at last but two mournful features were seen in the uttermost distance.”

Capturing wistful innocence was one of the hallmarks of Elgar’s compositional style, and the composer’s DNA is readily found in these piano miniatures. Elgar did produce a piano arrangement of the famed Enigma Variations, but I decided to focus on smaller pieces instead. Of course, Elgar also wrote a number of songs for voice and piano. Would you be interested to have them featured? Please let us know in the comments.