© jewishjournal.com

Today, we’re looking at ten pieces of classical music about freedom, from Beethoven’s opera set in prison to Undine Smith Moore’s defiant piano music about the experience of being Black in America.

Let’s get started:

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 3 (1806)

In Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, a Spanish nobleman named Florestan threatens to expose the corruption of a colleague named Pizarro. Pizarro wrongfully imprisons Florestan and tells the rest of the world that he has been killed.

However, Florestan’s wife, Leonore, refuses to believe the news. So she dresses up as a boy, renames herself Fidelio, and gets a job in the prison to find out what really happened to her husband.

By the end of the opera, Leonore ends up in front of her husband just before Pizarro actually goes to kill him. Pizarro, enraged, threatens to murder both husband and wife, but Fidelio/Leonore one-ups him by pulling out a gun, which puts an end to Florestan’s unjust imprisonment.

Beethoven had trouble writing an overture for this opera, and he wrote and discarded several versions. This one – known as the Leonore Overture No. 3 – is sometimes played after Leonore’s rescue of her husband.

Giuseppe Verdi: “Va, pensiero” from Nabucco (1841)

Verdi’s opera Nabucco tells the Biblical story of the Israelites’ exile in oppressive Babylon.

In the opera, the Israelite slaves sing it as they work, describing how, even in exile, their thoughts are with their homeland.

However, this was not the music’s only potential meaning in mid-nineteenth-century Italy. At that time, a movement for Italian independence and unification was gaining steam, and art and music helped to contribute to national pride and identity.

In 1844, a few years after the premiere of Nabucco, two brothers named Attilio and Emilio Bandiera were working for Italian unification when one of their followers betrayed them. They were taken into custody and died by firing squad, becoming martyrs for the cause.

Verdi did not necessarily endorse such a movement, but whether he liked it or not, his music likely contributed to the atmosphere that ultimately made the revolution possible.

Frédéric Chopin: Heroic Polonaise (1842)

Chopin was very proud of his Polish ancestry.

However, when he was twenty years old, he chose to leave Warsaw to make a musical career in a bigger city.

No sooner had he left for Vienna with his dear friend, political activist Tytus Woyciechowski, than Warsaw broke out into armed conflict.

The November Uprising in Warsaw lasted from November 1830 until October 1831. (Woyciechowski, for his part, as soon as he heard about the uprising, returned to Warsaw. Chopin stayed behind.)

The Poles fought their occupiers, the Russians, but were ultimately crushed.

Chopin was devastated when he heard about the outcome. He wrote in his journal, “Oh God! … You are there, and yet you do not take vengeance!”

Over the years that followed, he became increasingly obsessed with Polish identity. He began incorporating polonaises – a dance form that originated in Poland – into his piano music.

He also began dating Paris-based authoress George Sand, who backed the Polish cause in her writings. After he wrote the Heroic Polonaise, she drew a direct line between the Polonaise and other countries’ fights for freedom and self-determination, writing, “The inspiration! The force! The vigour! There is no doubt that such a spirit must be present in the [1848] French Revolution. From now on, this Polonaise should be a symbol, a heroic symbol.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 1812 Overture (1880)

The overture was commissioned to celebrate the completion of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in St. Petersburg.

Construction of the cathedral had started generations earlier as a gesture of thanksgiving to God after Napoleon’s ill-fated attempt to overtake Russia in 1812.

To celebrate the Russians’ preservation of their freedom, Tchaikovsky wrote an overture about the fight, featuring excerpts of the Marsaillaise and Russian folk songs.

He underlined the importance of the victory by writing parts for large orchestra, brass band, church bells, and even cannons.

Jean Sibelius: Finlandia (1899)

Finlandia is Sibelius’s single most famous work. It was written for the Press Celebrations of 1899, a Finnish event that protested press censorship by the Russian Empire.

In order to sidestep Russian censorship, the piece was initially performed under over-the-top innocuous titles like “Happy Feelings at the Awakening of Finnish Spring.”

However, the piece was not just about happy feelings; it was clearly also a rebellious call to arms against oppression.

Finlandia portrays struggle, then transitions into a serene melody symbolizing the noble spirit of the Finnish people. That serene melody might sound like an old hymn, but it was actually composed by Sibelius specifically for this work. The work ends with rousing energy.

Amy Beach: A Song of Liberty (1902)

American composer Amy Beach wrote A Song of Liberty for piano and women’s choir. In it, she set lyrics by Frank Lebby Stanton, the first poet laureate of Georgia.

The song traces themes about American national identity and liberty and how, in the narrator’s view, the American penchant for liberty stretches “from sounding sea to sea”, in words that echo Katharine Lee Bates’s lyrics for what later became known as “America the Beautiful.”

Hail to our Country! strong she stands,

Nor fears the war drum’s beat.

The sword of Freedom in her hands,

The tyrant at her feet!

Ethel Smyth: March of the Women (1910)

Composer Ethel Smyth was born in 1858 in Kent. She was a rebel from childhood, demanding to be allowed to study music in Europe and locking herself in her room until her father let her go.

Not surprisingly, she was a major supporter of the women’s suffrage movement. (She even taught activist Emmeline Pankhurst how to throw stones at windows.)

In 1910, she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union and actually went so far as to give up her musical career for two years to contribute to the movement.

She returned to music briefly in 1911 when she composed the March of the Women. During this time, she was arrested for her activism and imprisoned in Holloway Prison. Her fellow suffragettes would march in the prison yard singing the March while she’d conduct them leaning out the window with a toothbrush.

Undine Smith Moore: Before I’d Be A Slave (1953)

African-American composer Undine Smith Moore was born in Virginia in 1904 and died in 1989. By the end of her prolific career, she was known as “the Dean of Black Women Composers.” She often wove themes of the Black American experience into her work.

In 1953, she wrote a piece for solo piano called Before I’d Be a Slave. She described the program of the work:

It follows a program which I would hope is evident in the music without verbal explanation – in general:

In frustration and chaos of slaves who wish to be free

In the depths – a slow and ponderous struggle marked by attempts to escape-anyway-being bound-almost successful attempt at flight

Tug of war with the oppressors

A measure of freedom won – some upward movement less lacerating

Continued aspiration-determination-affirmation.

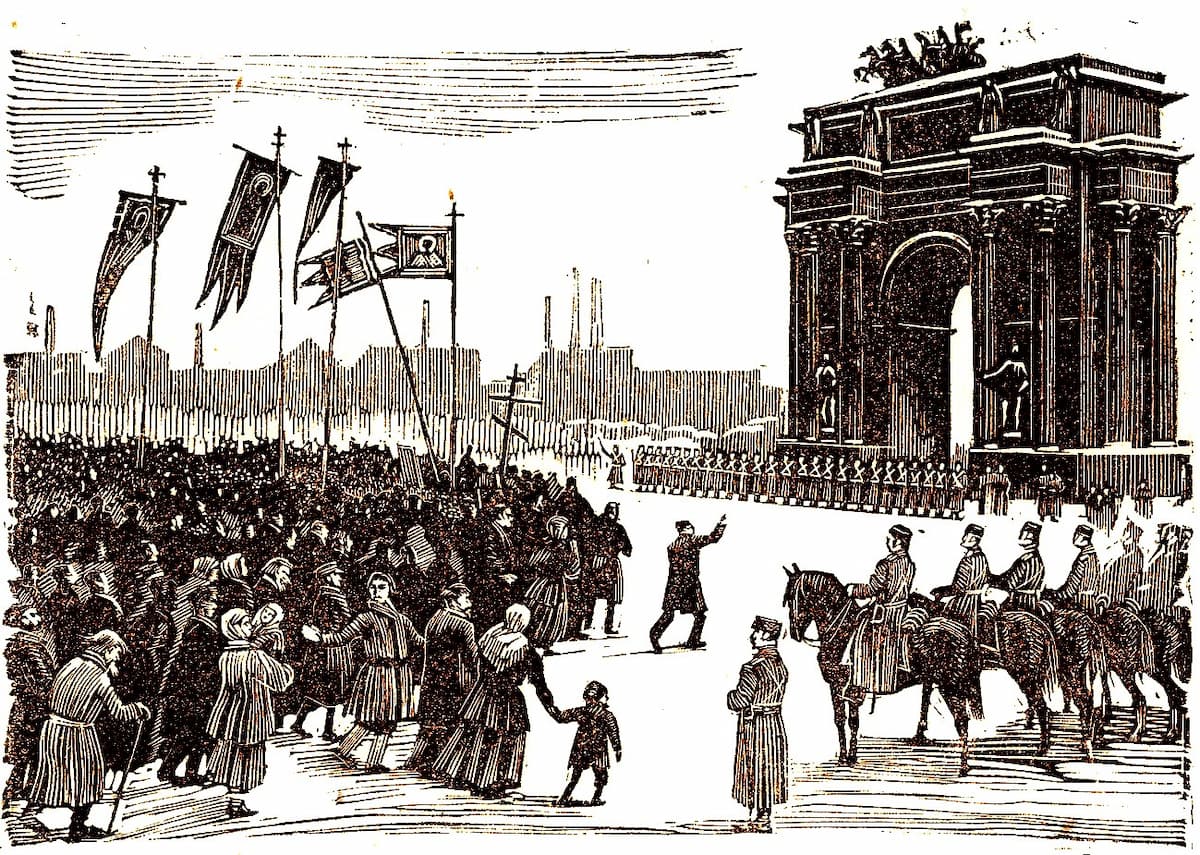

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 11 (1957)

In his eleventh symphony, Dmitri Shostakovich turned to the story of the 1905 Russian Revolution for creative inspiration.

This symphony has often been described as a soundtrack without a movie. It’s easy to see why: the work lasts for an hour with no breaks, and every movement contains a program.

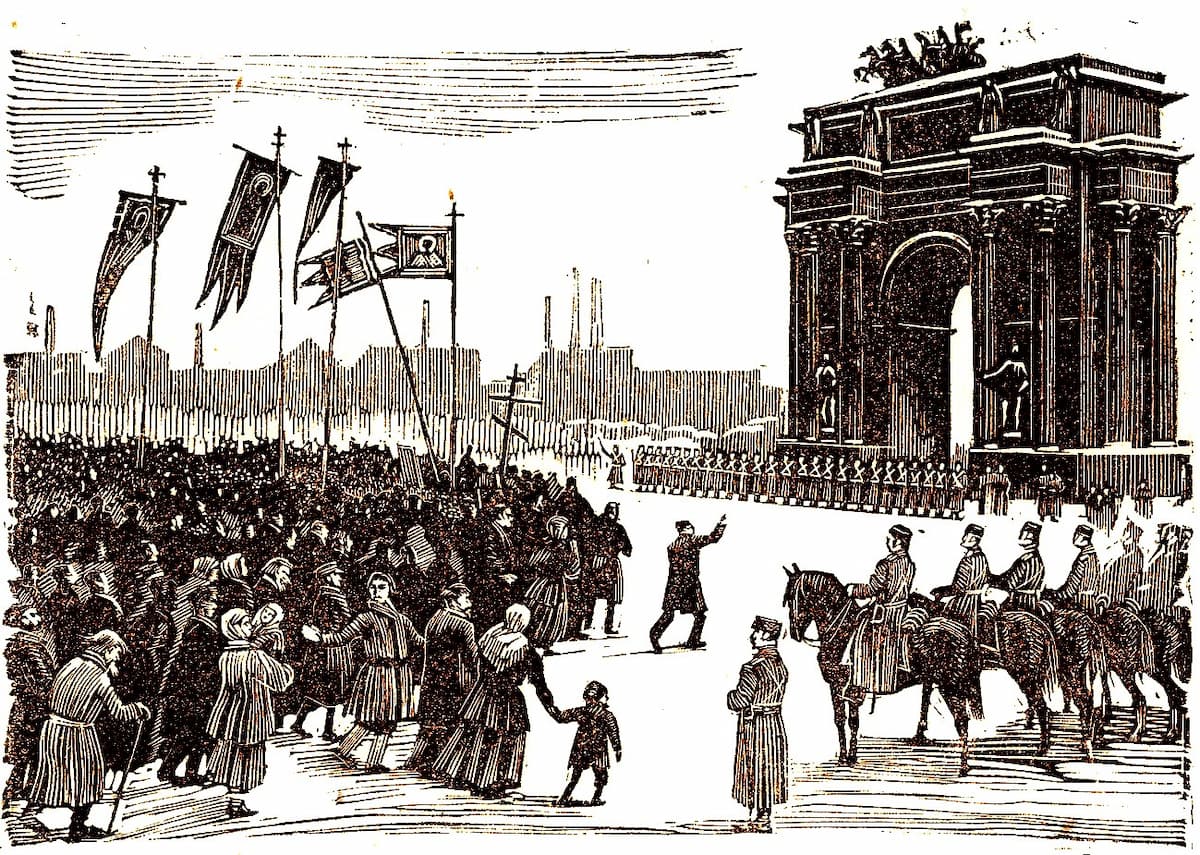

Demonstrations before Bloody Sunday © Wikipedia

The first movement is about the quiet in the Palace Square before unarmed protesters marching to the palace were shot by imperial forces. The second movement depicts the forces beginning to attack the crowd, while the third movement is a memorial to those who have just lost their lives. The finale hints at the 1917 revolution – in which the royal family was defeated once and for all.

It is possible – although not certain – that Shostakovich was inspired to write this symphony at least in part because he had sympathy for the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Testimony about his political positions is abundant and often contradictory. But aside from all of that, it is very easy to read a narrative of struggle, liberty, and self-determination into this music.

Frederic Rzewski: The People United Will Never Be Defeated! (1975)

Some people believe that this is among the greatest sets of themes and variations ever composed! It was written by composer Frederic Rzewski, an American composer who lived between 1938 and 2021.

This work consists of a Chilean protest song, ¡El pueblo unido jamás será vencido! (The people united will never be defeated!), and 36 variations on it.

Rzewski wrote the work as a commentary on the popular resistance to oppressive dictator Augusto Pinochet, who came to power with the support of the American government in 1973.

The work is massive, lasting an hour, and is also massively demanding. For one, the score asks the pianist to whistle and slam the piano lid!

Conclusion

Whenever people feel oppressed by any force, it is second nature to create or take comfort in music that expresses the pathos, fury, tragedy, and occasionally triumph that can arise when seeking freedom…and these ten works of classical music about freedom prove it!

What’s your favorite classical music about freedom?