It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, April 14, 2023

Theme to Exodus / London Pops Orchestra

月亮代表我的心 - The Moon, My Heart - Carl Doy

Italian Dishes or Classical Composers?

By Georg Predota, Interlude

© tastingtable.com

Cambini

Although we might easily imagine Cambini to be a lightly sautéed seafood dish from the Tuscany region, it actually identifies the Italian composer and violinist Giuseppe Maria Cambini (1746-1810). Born in Livorno, Cambini made his way to Paris and appeared as a celebrated soloist at the Concert Spirituel. He also was an extremely prolific composer, writing 82 Sinfonia concertantes, 9 symphonies, 17 concertos and over 100 string quintets! Yet, in the chronicles of music history we primarily know Cambini for his supposed hostilities towards Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart had his Sinfonia concertante (K. 297B) scheduled for performance at a concert Spirituel. However, Cambini reacted jealously, and in fear of his own reputation in Paris sabotaged the performance.

Falvetti

Would you believe that Falvetti designates an ancient pasta dish originating in the Kingdom of Naples? You have good reason to be suspicious, because I was referencing the Italian Baroque composer Michelangelo Falvetti (1642–1692). One of the most original musical personalities in the second half of the seventeenth century, Falvetti was born in Calabria but spend the majority of his career in various musical institutions in Sicily. He composed polyphonic masses, concertato psalms and motets for various voices and continuo, but only two complete works have survived. Among them is the Oratorio Il diluvio universal (The Flood), first performed in Messina in 1682. A typical work of the Counter Reformation, it musically combines theater and Catholic propaganda. Nevertheless, the score discloses penetrating knowledge of the Baroque musical traditions of Rome and Venice.

Mannelli

Not to be confused with a fictitious dessert from Liguria, Carlo Mannelli (1640-1697) was an Italian violinist, castrato and composer. A celebrated violinist who taught Arcangelo Corelli, Mannelli composed roughly 300 works including 86 violin sonatas, 24 trio sonatas, 58 sinfonias and some vocal works. However, only a handful of works have actually come down to us in manuscript form. The same is true for a violin treatise entitled Studio del Violino, which has also been lost. Earning the nickname “Carlo del Violino,” the composer skillfully combined the virtuoso and lyrical potential of the violin. His sonata da chiesa “La Foggia,” contains a part for obbligato lute and is dedicated to the composer Francesco Foggia.

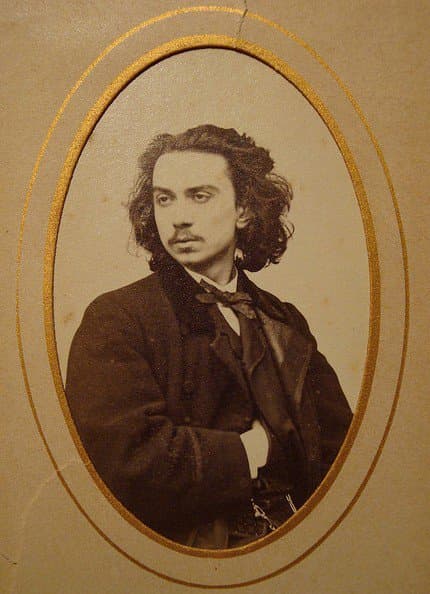

Sgambati

Giovanni Sgambati

The deliciously sweet concoction “Sgambati,” a fried sweet dough ball with coconut cream filling, is primarily served around Christmas time in the province of Alto Adige in northern Italy. Although it all sounds rather delicious, a dish by that name simply does not exist! Rather, the name Sgambati identifies an Italian pianist and composer who was responsible for the rebirth of Italian instrumental music at the end of the 19th century. Born in Rome, Sgambati studied with Franz Liszt and systematically explored the world of instrumental music. Richard Wagner called him “a true, great and original talent,” and his First Symphony blends Italian melodic style and the German orchestral tradition. The work was immediately successful and became part of the standard repertoire of the conductors Martucci and Toscanini.

Thursday, April 13, 2023

Leopold Anthony Stokowski - his music and his life

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appearance in the Disney film Fantasia with that orchestra. He was especially noted for his free-hand conducting style that spurned the traditional baton and for obtaining a characteristically sumptuous sound from the orchestras he directed.

Stokowski was music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the NBC Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the Symphony of the Air and many others. He was also the founder of the All-American Youth Orchestra, the New York City Symphony, the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra and the American Symphony Orchestra.

Stokowski conducted the music for and appeared in several Hollywood films, most notably Disney's Fantasia, and was a lifelong champion of contemporary composers, giving many premieres of new music during his 60-year conducting career. Stokowski, who made his official conducting debut in 1909, appeared in public for the last time in 1975 but continued making recordings until June 1977, a few months before his death at the age of 95.

Biography

Early life

The son of an English-born cabinet-maker of Polish heritage, Kopernik Joseph Boleslaw Stokowski, and his Northampton-born wife Annie-Marion (née Moore), Stokowski was born Leopold Anthony Stokowski, although on occasion in later life he altered his middle name to Antoni, per the Polish spelling. There is some mystery surrounding his early life. For example, he spoke with an unusual, non-British accent, though he was born and raised in London. On occasion, Stokowski gave his year of birth as 1887 instead of 1882, as in a letter to the Hugo Riemann Musiklexicon in 1950, which also incorrectly gave his birthplace as Kraków. Nicolas Slonimsky, editor of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, received a letter from a Finnish encyclopaedia editor that said, "The Maestro himself told me that he was born in Pomerania, Germany, in 1889." In Germany there was a corresponding rumour that his original name was simply "Stock" (German for stick). However, Stokowski's birth certificate (signed by J. Claxton, the registrar at the General Office, Somerset House, London, in the parish of All Souls, County of Middlesex) gives his birth on 18 April 1882, at 13 Upper Marylebone Street (now New Cavendish Street), in the Marylebone District of London. Stokowski was named after his Polish-born grandfather Leopold, who died in the English county of Surrey on 13 January 1879, at the age of 49.

The mystery surrounding his origins and accent is clarified in Oliver Daniel's 1000-page biography Stokowski – A Counterpoint of View (1982), in which (in Chapter 12) Daniel reveals Stokowski came under the influence of his first wife, American pianist Olga Samaroff. Samaroff, born Lucy Mary Agnes Hickenlooper, was from Galveston, Texas, and adopted a more exotic-sounding name to further her career. For professional and career reasons, she "urged him to emphasize only the Polish part of his background" once he became a resident of the United States. He studied at the Royal College of Music, where he first enrolled in 1896 at the age of thirteen, making him one of the youngest students to do so. In his later life in the United States, Stokowski would perform six of the nine symphonies composed by his fellow organ student Ralph Vaughan Williams. Stokowski sang in the choir of the St Marylebone Parish Church, and later he became the assistant organist to Sir Walford Davies at The Temple Church. By age 16, Stokowski was elected to membership of the Royal College of Organists. In 1900, he formed the choir of St. Mary's Church, Charing Cross Road, where he trained the choirboys and played the organ. In 1902, he was appointed the organist and choir director of St. James's Church, Piccadilly. He also attended The Queen's College, Oxford, where he earned a Bachelor of Music degree in 1903.

New York, Paris, and Cincinnati

In 1905, Stokowski began work in New York City as the organist and choir director of St. Bartholomew's Church. He was very popular among the parishioners, who included members of the Vanderbilt family, but in the course of time, he resigned this position in order to pursue a career as an orchestra conductor. Stokowski moved to Paris for additional study in conducting. There he heard that the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra would be needing a new conductor when it returned from a long sabbatical. In 1908, Stokowski began a campaign to win this position, writing letters to Mrs. Christian R. Holmes, the orchestra's president, and travelling to Cincinnati, Ohio, for a personal interview.

Stokowski was selected over other applicants and took up his conducting duties in late 1909. That was also the year of his official conducting debut in Paris with the Colonne Orchestra on 12 May 1909, when Stokowski accompanied his bride to be, the pianist Olga Samaroff, in Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1. Stokowski's conducting debut in London took place the following week on 18 May with the New Symphony Orchestra at Queen's Hall. His engagement as new permanent conductor in Cincinnati was a great success. He introduced the concept of "pops concerts" and, starting with his first season, he began championing the work of living composers. His concerts included performances of music by Richard Strauss, Sibelius, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Glazunov, Saint-Saëns and many others. He conducted the American premieres of new works by such composers as Elgar, whose 2nd Symphony was first presented there on 24 November 1911. He was to maintain his advocacy of contemporary music to the end of his career. However, in early 1912, Stokowski became frustrated with the politics of the orchestra's Board of Directors, and submitted his resignation. There was some dispute over whether to accept this or not, but, on 12 April 1912, the board decided to do so.[citation needed]

Philadelphia Orchestra

Leopold Stokowski historical marker at 240 S. Broad St., Philadelphia

Two months later, Stokowski was appointed the director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he made his conducting debut in Philadelphia on 11 October 1912. This position would bring him some of his greatest accomplishments and recognition. It has been suggested that Stokowski resigned abruptly at Cincinnati with the hidden knowledge that the conducting position in Philadelphia was his when he wanted it, or as Oscar Levant suggested in his book A Smattering of Ignorance, "he had the contract in his back pocket." Before Stokowski moved into his conducting position in Philadelphia, however, he returned to England to conduct two concerts at the Queen's Hall in London. On 22 May 1912, Stokowski conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in a concert that he was to repeat in its entirety 60 years later at the age of 90, and on 14 June 1912, he conducted an all-Wagner concert that featured the noted soprano Lillian Nordica. While he was director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, he was largely responsible for convincing Mary Louise Curtis Bok to set up the Curtis Institute of Music (13 October 1924) in Philadelphia. He helped with recruiting faculty and hired many of their graduates.[citation needed]

Stokowski rapidly gained a reputation as a musical showman. His flair for the theatrical included grand gestures, such as throwing the sheet music on the floor to show he did not need to conduct from a score. He also experimented with new lighting arrangements in the concert hall, at one point conducting in a dark hall with only his head and hands lighted, at other times arranging the lights so they would cast theatrical shadows of his head and hands. Late in the 1929-1930 symphony season, Stokowski started conducting without a baton. His free-hand manner of conducting soon became one of his trademarks. On the musical side, Stokowski nurtured the orchestra and shaped the "Stokowski" sound, or what became known as the "Philadelphia Sound".He encouraged "free bowing" from the string section, "free breathing" from the brass section, and continually altered the seating arrangements of the orchestra's sections, as well as the acoustics of the hall, in response to his urge to create a better sound. Stokowski is credited as the first conductor to adopt the seating plan that is used by most orchestras today, with first and second violins together on the conductor's left, and the violas and cellos to the right

Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra at 2 March 1916 American premiere of Mahler's 8th Symphony

Stokowski also became known for modifying the orchestrations of some of the works that he conducted, as was a standard practice for conductors prior to the second half of the 20th century. Among others, he amended the orchestrations of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Brahms. For example, Stokowski revised the ending of the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, by Tchaikovsky, so it would close quietly, taking his notion from Modest Tchaikovsky's Life and Letters of Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky (translated by Rosa Newmarch: 1906) that the composer had provided a quiet ending of his own at Balakirev's suggestion. Stokowski made his own orchestration of Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain by adapting Rimsky-Korsakov's orchestration and making it sound, in some places, similar to Mussorgsky's original. In the film Fantasia, to conform to the Disney artists' story-line, depicting the battle between good and evil, the ending of Night on Bald Mountain segued into the beginning of Schubert's Ave Maria.

Many music critics have taken exception to the liberties Stokowski took—liberties which were common in the nineteenth century, but had mostly died out in the twentieth, when faithful adherence to the composer's scores became more common

Stokowski's repertoire was broad and included many contemporary works. He was the only conductor to perform all of Arnold Schoenberg's orchestral works during the composer's own lifetime, several of which were world premieres. Stokowski gave the first American performance of Schoenberg's Gurre-Lieder in 1932. It was recorded "live" on 78 rpm records and remained the only recording of this work in the catalogue until the advent of the LP Record. Stokowski also presented the American premieres of four of Dmitri Shostakovich's symphonies, Numbers 1, 3, 6, and 11. In 1916, Stokowski conducted the American premiere of Mahler's 8th Symphony, Symphony of a Thousand, whose premiere he had attended in Munich on 12 September, 1910[10] He added works by Rachmaninoff to his repertoire, giving the world premieres of his Fourth Piano Concerto, the Three Russian Songs, the Third Symphony, and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini; Sibelius, whose last three symphonies were given their American premieres in Philadelphia in the 1920s; and Igor Stravinsky, many of whose works were also given their first American performances by Stokowski. In 1922, he introduced Stravinsky's score for the ballet The Rite of Spring to America, gave its first staged performance there in 1930 with Martha Graham dancing the part of The Chosen One, and at the same time made the first American recording of the work.[citation needed]

Seldom an opera conductor, Stokowski did give the American premieres in Philadelphia of the original version of Mussorgky's Boris Godunov (1929) and Alban Berg's Wozzeck (1931). Works by such composers as Arthur Bliss, Max Bruch, Ferruccio Busoni, Carlos Chávez, Aaron Copland, George Enescu, Manuel de Falla, Paul Hindemith, Gustav Holst, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Walter Piston, Francis Poulenc, Sergei Prokofiev, Maurice Ravel, Ottorino Respighi, Albert Roussel, Alexander Scriabin, Elie Siegmeister, Karol Szymanowski, Edgard Varèse, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Anton Webern, and Kurt Weill, received their American premieres under Stokowski's direction in Philadelphia. In 1933, he started "Youth Concerts" for younger audiences, which are still a tradition in Philadelphia and many other American cities, and fostered youth music programs. After disputes with the board, Stokowski began to withdraw from involvement in the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1936 onwards, allowing his co-conductor Eugene Ormandy to gradually take over. Stokowski shared principal conducting duties with Ormandy from 1936 to 1941; Stokowski did not appear with the Philadelphia Orchestra from the closing concert of the 1940–41 season (a semi-disastrous performance of Bach's St. Matthew Passion) until 12 February 1960, when he guest-conducted the Philadelphia in works of Mozart, Falla, Respighi, and in a legendary performance of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, arguably the greatest by Stokowski. The recording of this concert's broadcast had been circulated privately among collectors over the years, though never issued commercially, but with the copyright expiring at the start of 2011, it was released in its entirety on the Pristine Audio label.[citation needed]

Stokowski appeared as himself in the motion picture The Big Broadcast of 1937, conducting two of his Bach transcriptions. That same year he also conducted and acted in One Hundred Men and a Girl, with Deanna Durbin and Adolphe Menjou. In 1939, Stokowski collaborated with Walt Disney to create the motion picture for which he is best known: Fantasia. He conducted all the music (with the exception of a "jam session" in the middle of the film) and included his own orchestrations for Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D minor and Mussorgsky's/Schubert's Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria. Stokowski even got to talk to (and shake hands with) Mickey Mouse on screen, in a famous silhouette footage; though, he would later say with a smile that Mickey Mouse got to shake hands with him.

A lifelong and ardent fan of the newest and most experimental techniques in recording, Stokowski saw to it that most of the music for Fantasia was recorded over Class A telephone lines laid down between the Academy of Music in Philadelphia and Bell Laboratories in Camden NJ, using an early, highly complex version of multi-track stereophonic sound, dubbed Fantasound, which shared many attributes with the later Perspecta stereophonic sound system. Recorded on photographic film, the only suitable medium then available, the results were considered astounding for the latter half of the 1930s.

Upon his return in 1960, Stokowski appeared with the Philadelphia Orchestra as a guest conductor. He also made two LP recordings with them for Columbia Records, one including a performance of Manuel de Falla's El amor brujo, which he had introduced to America in 1922 and had previously recorded for RCA Victor with the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra in 1946, and a Bach album which featured the 5th Brandenburg Concerto and three of his own Bach transcriptions. He continued to appear as a guest conductor on several more occasions, his final Philadelphia Orchestra concert taking place in 1969.

In honor of Stokowski's vast influence on music and the Philadelphia performing arts community, on 24 February 1969, he was awarded the prestigious University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit. Beginning in 1964, this award was "established to bring a declaration of appreciation to an individual each year that has made a significant contribution to the world of music and helped to create a climate in which our talents may find valid expression."[citation needed]

Classic FM Live 2023 at the Royal Albert Hall: photos from our night of operatic hits

Classic FM Live 2023 at the Royal Albert Hall: photos from our night of operatic hits

12 April 2023, 21:27 | Updated: 13 April 2023, 11:55

By Maddy Shaw Roberts

Explore all the photo highlights from Classic FM Live on 12 April, when we filled the Royal Albert Hall with lights, fireworks and the greatest hits of opera.

Classic FM Live with Viking returned to London’s Royal Albert Hall on 12 April 2023 for a sparkling night at the opera.

World-renowned soprano Danielle De Niese, star American baritenor Michael Spyres, and boy treble Malakai Bayoh, took to the stage to sing enduring operatic melodies – from arias ‘Habanera’ and ‘Nessun dorma’, to great opera overtures by Mozart and Verdi.

Opening with Carl Orff’s monumental ‘O Fortuna’ from Carmina Burana, the English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus were our ensemble and choir for the evening, performing music from Carmen, La Traviata, Madame Butterfly and The Marriage of Figaro under the baton of Paul Daniel.

Explore our selection of photo highlights below...

Welcome to the stage – the English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus!

Conductor Paul Daniel leads the English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Picture: Matt Crossick Your hosts for the evening, Alexander Armstrong and Myleene Klass...

Alexander Armstrong and Myleene Klass host Classic FM Live at the Royal Albert Hall. Picture: Matt Crossick Superstar soprano Danielle De Niese performs ‘Habanera’ from Carmen

Danielle De Niese sings ‘Habanera’ from Carmen. Picture: Matt Crossick Danielle De Niese with Agustín Lara’s thrilling ‘Granada’

Danielle De Niese with Agustín Lara’s thrilling ‘Granada’. Picture: Matt Crossick American baritenor Michael Spyres delights with Rossini’s ‘Figaro’ aria

Michael Spyres delights audience with Rossini’s ‘Largo al factotum’. Picture: Matt Crossick Maestro Paul Daniel leads the English National Opera Chorus

English National Opera Chorus led by Paul Daniel. Picture: Matt Crossick Michael Spyres entertains with vocal acrobatics in ‘Figaro’ aria

Michael Spyres entertains with vocal acrobatics in ‘Figaro’ aria. Picture: Matt Crossick Glorious Mozart and Verdi overtures from the English National Opera Orchestra

Mozart and Verdi overtures from the English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Picture: Matt Crossick Michael Spyres brings the house down with Puccini’s ‘Nessun dorma’

Michael Spyres sings Puccini's aria 'Nessun dorma'. Picture: Matt Crossick Boy treble Malakai Bayoh makes his Royal Albert Hall solo debut

Malakai Bayoh sings Handel at Classic FM Live. Picture: Matt Crossick Paul Daniel congratulates Malakai on his performance and standing ovation!

Paul Daniel gives Malakai Bayoh a fist-bump. Picture: Matt Crossick English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus under the baton of Paul Daniel

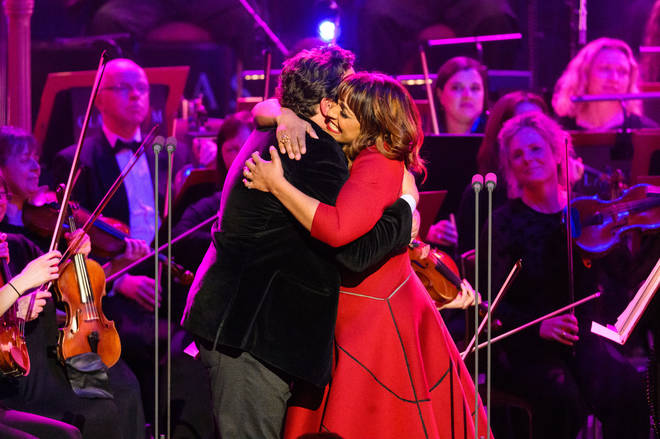

English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus under the baton of Paul Daniel. Picture: Matt Crossick Michael Spyres and Danielle De Niese duet on Verdi’s ‘Drinking Song’

Michael Spyres and Danielle De Niese sing Verdi’s ‘Drinking Song’. Picture: Matt Crossick Chorus and audience sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to the star soloists!

Michael Spyres and Danielle De Niese embrace at Classic FM Live. Picture: Matt Crossick Confetti rains down for a grand finale from the English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus

English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Picture: Matt Crossick

Monday, April 10, 2023

Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.2 tops Classic FM Hall of Fame in composer’s 150th anniversary year

There’s a new number one in the Classic FM Hall of Fame, as Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto tops the chart for the first time in 10 years.

Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No.2 has topped the Classic FM Hall of Fame for the first time in 10 years, in the year that marks 150 years since the composer was born.

A long-time favourite in the world’s biggest survey of classical music tastes, the monumental work has reached the No.1 spot eight times since the chart began in 1996.

In recent years it has lost out to Vaughan Williams’ enduringly popular The Lark Ascending, which has enjoyed four consecutive years in the top spot before being knocked off in 2023.

The new chart, which was revealed live across the four-day Easter weekend on Classic FM, also sees a record number of film music entries with 35 soundtracks voted in.

View the full Top 300 >

Rachmaninov finished writing his second piano concerto in 1901, as he emerged from a period of particularly troubling mental health. He dedicated the piece to the neurologist Nikolai Dahl as thanks for his treatment and support throughout his illness.

The piece was premiered in November of that year to great acclaim, and remains a firm favourite more than a century later. It featured prominently in the soundtrack of the 1945 romantic drama, Brief Encounter, and provided Eric Carmen with the inspiration for his hit pop power ballad, ‘All by Myself’, in 1975.

The tune cemented its popularity in 1996, when Canadian vocal powerhouse Celine Dion famously released her cover – and further still, when it was featured to great comedic effect in the 2001 film Bridget Jones’ Diary.

Friday, April 7, 2023

Top 30 Most Underrated Classical Composers

Most Fun Classical Songs and Popular Tunes for Easter

By Hermione Lai, Interlude

Pandemics come and pandemics go, but Easter will surely return every year. For many Christians around the world this is the most important holiday of the year. It commemorates the Passion of Christ, starting with the Last Supper and culminating with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. But above all, it celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The time around Easter, in many cultures and in different parts of the world is connected with a sense of renewal. Hurrah, Spring is finally coming!

Pandemics come and pandemics go, but Easter will surely return every year. For many Christians around the world this is the most important holiday of the year. It commemorates the Passion of Christ, starting with the Last Supper and culminating with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. But above all, it celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The time around Easter, in many cultures and in different parts of the world is connected with a sense of renewal. Hurrah, Spring is finally coming!

Here Comes Peter Cottontail

“Here comes Peter Cottontail”

Easter is not just a religious or nature ritual, but it is also connected with some very fun traditions for children and for those young at heart. And Easter wouldn’t be Easter without some beautiful, popular, uplifting and joyful music. So here comes my personal playlist of the most fun classical songs and popular tunes for Easter. Let’s get started with the long-eared and short-tailed creature who delivers decorated eggs to well-behaved children on Easter Sunday. Yes, I am talking about the Easter Bunny. You won’t find him mentioned in the bible, but Peter Cottontail is definitely a hugely popular Easter tradition.

Duke Ellington: Cotton Tail (Dee Dee Bridgewater)

Duke Ellington

The young Easter Bunny Peter Cottontail lives in April Valley together with his fellow Easter Bunnies. They make Easter candies, sew bonnets, and they decorate and deliver Easter eggs. But trouble starts brewing when Peter Cottontail, who is somewhat unreliable and gossipy, is supposed to be appointed Chief Easter Bunny. An evil rabbit named January Q. Irontail also wants the job, but his motivation is a little different. He wants to ruin Easter for children as revenge for a child roller-skating over his tail. Now he has to wear an artificial tail, and he is not a happy bunny. After much intrigue, scheming, and treachery, Irontail does become the new Chief Easter Bunny. He quickly passes various laws to make Easter a disaster. Eggs have to be painted brown and gray, candy sculptors become tarantulas and octopuses, and instead of Easter bonnets, he orders that Easter rubber boots be made. Of course, things do work out in the end, and Cottontail, all reformed and reliable becomes the official Chief Easter Bunny.

Peter Rabbit

The animated television special of Peter Cottontail dates from 1971, but the character of Peter Rabbit has a long tradition in children’s literature. Beatrix Potter first introduced Peter Rabbit in 1902. It became a huge hit, and she wrote five more books on the subject. “Cottontail” also became the inspiration for the great American composer, pianist and jazz orchestra leader Duke Ellington. When he returned to the US after a successful tour of Europe in 1940, he composed the jazz standard “Cotton Tail.” For jazz aficionados the tune “foreshadows bebop in the rhythmic inflections and melody line.” Jon Hendrick wrote the lyrics accompanying the tune based on the familiar Peter Rabbit fairytale. Personally, I really love the scat tribute to Ella Fitzgerald performed by Dee Dee Bridgewater, as her voice skips and hops across the musical landscape.

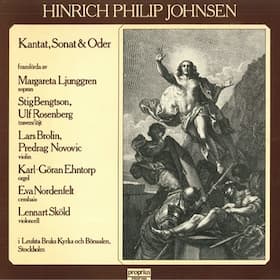

Philip Henrik Johnsen: Church Music-Easter Sunday 1757 “Allegro”

Hinrich Philip Johnsen

Our next Easter selection takes us to a completely different time and place. The time is the mid-18th century, and the place is Stockholm in Sweden. There had been a bit of trouble deciding on the royal succession, and in the end Adolf Fredrik, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was elected to the throne of Sweden. The Duke had to pick up his entire household for his move to Stockholm, and he brought his own musicians along. That included a young clavier player named Hinrich Philip Johnsen (1717-1779). He probably hailed from Germany, and he was regarded as a prominent contrapuntist and organ improviser. He composed some delightful and cheerful music for the Easter Sunday service in 1757. The reason we know that it was composed in 1757 is because the composer put the date in the title. The music is very cheerful indeed, and even though the composer is not a household name, it’s a really fun Classical Song for Easter.

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Festival, Op. 36

Russian Easter Festival

Everybody has his or her favorite Easter traditions and memories. The Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov remembers the celebration of Easter “as a large gathering of people from every walk of life, with several popes conducting cathedral service… the old liturgical chants and nearby monastery bells ringing out.” In 1887/88 he decided to musically encode his childhood memories, growing up in Tikhvin, in Novgorod province. The orchestra was Rimsky-Korsakov’s instrument, and he composed a brilliant and wonderful score. As he wrote, “I want to reproduce the legendary and heathen aspect of the holiday, and the transition from the solemnity and mystery of the evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious celebrations of Easter Sunday morning.” You can hear all the excitement of the crowds in that beautiful and fun Classical Song for Easter.

Vally Weigl, wife of Karl Weigl © Weigl Foundation

Karl Weigl: 6 Children Songs, No. 4 “To the Easter Bunny”

Karl Weigl was born in Vienna in February 1881. He showed some exceptional musical talent and his parents sent him for private lessons with Alexander Zemlinsky. From his very beginnings as a composer, it became clear that he had a passion for vocal music. His settings of “Six Children’s Songs” to poems by his second wife Vally date from between 1932-1944. They are written in English because Weigl and his family had to flee to the United States when Hitler annexed Austria in 1938. Weigl had a gift for melodic invention, “as well as simple onomatopoeic devices such as the hopping appoggiaturas in his “To the Easter Bunny.” It’s all about the Easter Bunny delivering his brightly-colored Easter eggs. What a fun and hopping Classical song for Easter.

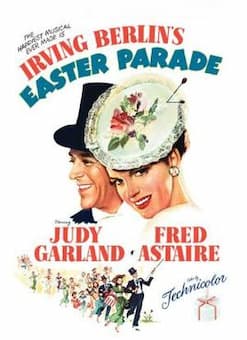

Irving Berlin: Easter Parade

Easter Parade

Easter Parades are said to date back to the early days of Christianity. But they really got going in New York City in the mid-1800s. It was an entirely social event. After the upper crust of society attended Easter services at various churches alongside Fifth Avenue, they strolled outside to show off their new spring outfits and hats. They soon attracted ordinary onlookers wanting to see what the rich and famous were up to, and the tradition of the Easter parade was born. It was highly popular during the mid-20th century, and it even inspired the very popular film “Easter Parade” in 1948. Starring Fred Astaire and Judy Garland, the music was composed by Irving Berlin. Plenty of popular tunes for Easter in that hit production.

Irving Berlin: Easter Parade (MGM Studio Orchestra; Johnny Green, cond.; Roger Edens, piano; Betty Rome, vocals; Blanche Arnaud, vocals; Camilla Holliday, vocals; Fred Astaire, vocals; Gene Curtsinger, vocals; Loolie Jane Norman, soprano; Misses Doxie, vocals; Mel-Tones, vocals; Judy Garland, vocals; Peter Lawford, vocals; Ann Miller, vocals; Dick Beavers, vocals; Clinton Sundberg, vocals; The Lyttle Sisters, choir; Eadie Griffith, piano; Rack Goodwin, piano; MGM Studio Chorus, choir)

Bonnie and Clyde

Thomas Newman: The Highwaymen, “Easter Morning”

Talking about films, in 2019 Kevin Costner and Woody Harrelson starred in the period crime drama “The Highwaymen”. Essentially, it’s the famed story of the notorious outlaws Bonnie and Clyde, and includes a haunting track detailing some sad events on “Easter Morning.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Jesus Christ Superstar, “I don’t know how to love him”

Jesus Christ Superstar © Pamela Raith

Andrew Lloyd Webber is called “the most commercially successful composer in history.” Several of his musicals have run for more than a decade in the West End and on Broadway, and surely you know such hit songs as “The Music of the Night” from The Phantom of the Opera, “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” from Evita, and “Memory” from Cats. One of his earlier and rather controversial projects was the 1970 rock opera “Jesus Christ Superstar.” The story is loosely based on the accounts of the last week of Jesus’ life, and it focuses on the personal psychology of the characters. Audiences were rather shocked by the controversial portrayals of Mary Magdalene, and her unrequited love for Jesus. “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” presents her personal confusion in understanding her attraction to Jesus. This gorgeous tune became hugely popular, and it stormed the pop hit charts.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: “Fantaisie tableaux,” Suite No. 1, Op. 5, No. 4 “Pâques (Easter)”

Rachmaninoff, 1901

As a boy, Sergei Rachmaninoff was frequently taking to Russian Orthodox Church services by his grandmother. He was absolutely enchanted by the rituals, and the sounds of church bells and liturgical chants never left him. His Suite No. 1 for two pianos dates from the summer of 1893, and as he explained, “it consists of a series of musical pictures.” Maybe, these musical pictures are based on poetic excerpts, and the work is dedicated to Tchaikovsky. The final tone picture is called Pâques (Easter), and it takes us back to Rachmaninoff’s childhood and the beautiful ringing of bells. For me personally, it is one of the most fun Classical songs for Easter. Easter celebrations and traditions vary widely across the world. No matter how you celebrate Easter or the coming of Spring, there is plenty of fantastic music for that special occasion. What are some of your musical Easter favourites?