It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, September 5, 2022

Ocean Deep - Cliff Richard (Lyrics) 🎵

Time To Say Goodbye - Ernesto Cortazar

Chamber Music by Women Composers

Röntgen-Maier, La Guerre, Price, Frank, and Pejačević

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Amanda Röntgen-Maier

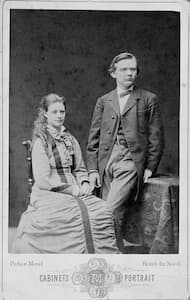

The violinist and composer Amanda Röntgen-Maier (1853–1894) created a sensation when she became Sweden’s first-ever female Director of the Music at the Conservatory in Stockholm in 1872. Maier decided to continue her private studies in Leipzig with the concertmaster of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Engelbert Röntgen. She met and became acquainted with Brahms, Joachim, Grieg and Clara Schumann, who greatly admired her. She publically performed many of her own compositions with her future husband Julius Röntgen, son of Engelbert. The married couple moved to Amsterdam, where Amanda spent her time on housekeeping and motherhood. “Her composing faded into the background and her concertizing came to an almost complete halt, as in bourgeois society, public appearances were considered unfitting for a married woman.” In 1886 Röntgen-Maier fell seriously ill, and by the time of her death at the age of 41, she was practically forgotten.

Amanda Röntgen-Maier and Julius Röntgen

During her time in Leipzig she met fellow student Ethel Smyth, and despite their differences in character, they became friends. When Smyth looked back at her time with the Röntgen’s in Leipzig in her memoirs, she wrote, “there was one more belonging to that household, a dear Swedish girl called Amanda Maier, violinist and composer, who afterwards married Julius; an then for the first time I saw a charming blend of art and courtship very common those days.” When she heard of Amanda’s death, she wrote to Julius Röntgen, “I dare not think about how you will endure this—still I envy you in that respect that you have known her better than all the rest of us… It was one of the most beautiful beings that I had ever seen… the only bearable for you must be to know that no human being that has met her will ever be able to rid itself of the impression of her personality.” Röntgen-Maier composed a number of violin sonatas and a concerto for her instrument. The E-minor piano quartet was composed during a trip to Norway in 1891, and it was her final major composition.

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665-1729) was the first woman in France to compose an opera. Born into a family of master masons and musicians, she played the harpsichord and sang at the court of Louis XIV from the age of five. Madame de Montespan kept Élisabeth in her entourage for three years, and her first composition were divertissements intended for court. She married the organist Marin de La Guerre in 1684 and left the gilded world of Versailles for Paris. “She gave lessons and concerts for which she was soon renowned throughout the city.” Élisabeth published her “First book of harpsichord pieces” at the age of twenty-two, but her tragédie lyrique Céphale et Procris, “staged at the Académie Royale de Musique met with disapproval.” She abandoned any other dramatic projects and focused on composing sonatas, a new and highly popular emerging genre.

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

She was invited to present her work at court, and the sonatas were “played quite perfectly by the Marchand brothers. A contemporary eyewitness reports, “After dinner, his Majesty spoke most obligingly to Mme de La Guerre, and after heaping praise on her sonatas, told her that they were like nothing else. One could offer Mme de La Guerre no higher praise, since these words signified not only that the King had found her music extremely fine, but also that it is original, something that is extremely rare nowadays.” Her sonatas “are conspicuous for their variety, rhythmic vigour and expressive harmony, as well as for certain innovative features in the violin writing.” Inspired by her sonatas alternate between Italian and French idioms. “The former is present in the expressive opening movements, the incisive rhythms and the fugal sections of the fast movements. The composer remains true to the French aesthetic in the dances featured in some of the sonatas, the use of the viol as a solo instrument, and the melodic vein of the arias.”

Florence Price

In 1943, Florence Price (1887-1953) wrote a letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky in which she referred explicitly to her two handicaps. She told him that “music written by women in general are preconceived by many to be light, froth, lacking in depth, logic and virility, and that she wanted her music to be judged on merit alone.” Price felt that she suffered from a second affliction, her race as an African American. Price was actually of mixed racial heritage, African, European and Native American. Her mother was worried that “anything pertaining to a black racial identity would preclude her daughter’s success. As such, she encouraged her daughter to present herself as Mexican.” Price nevertheless made history when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Frederick Stock premiered her award-winning Symphony in E minor in 1933. Critics raved about the premiere and “hoped that this would bring about a new era, one where the concert hall would finally welcome black classical artists.”

Florence Price at the piano, University of Arkansas

Price was celebrated during her time, but she continued to face gender and race barriers. At the time of her death, the majority of her music remained unpublished, “and a significant quantity of her manuscripts had disappeared without trace. It was not until 2009 that a cache of them, including two lost symphonies, was discovered by property developers in the attic of an abandoned house in Illinois.” That cache included a Piano Quintet in A minor with an inscription added by Price in 1952. However, musicologists have suggested that the “work might have been written around 1936, the date of her well-known E-minor quintet.” Written in a late-romantic idiom, “the piece celebrates African American heritage by echoing the musical language of spirituals and hymns (second movement), and reworking elements of the popular juba stomping dance that hailed from the slave plantations of the Deep South (third movement).” The A minor Quintet was first published in 2017.

Gabriela Lena Frank

Born in 1972 in Berkeley, California, Gabriela Lena Frank, daughter to a mother of mixed Peruvian/Chinese ancestry and a father of Lithuanian/Jewish descent, explores her multicultural heritage through her compositions. Taking inspiration from the fieldwork of Bela Bartók and Alberto Ginastera, Frank has travelled extensively throughout South America and “her pieces reflect and refract her studies of Latin-American folklore, incorporating poetry, mythology, and native musical styles into a western classical framework.” Frank has been nominated for Grammys as both composer and pianist, and she holds a Guggenheim Fellowship and a USA Artist Fellowship given each year to fifty of the country’s finest artists. Her work has been described as “crafted with unselfconscious mastery,” “brilliantly effective,” “a knockout,” and “glorious.” She is a member of the Silk Road Ensemble and receives regular commissions from Yo Yo Ma, the Kronos Quartet and a host of leading orchestras.

Identity is always at the center of Frank’s music, and as a musical anthropologist she travels extensively through South America. She writes, “there is usually a story line behind my music, a scenario or character.” Such is certainly the case in her Leyendas (Legends): “An Andean Walkabout.” Composed in 2001, she explains “An Andean Walkabout for string quartet, later arranged for string orchestra, draws inspiration from the idea of mestizaje as envisioned by the Peruvian writer José María Arguedas, where cultures can coexist without the subjugation of one by the other. As such, this piece mixes elements from the western classical and Andean folk music traditions.” Frank incorporates a wide variety of Andean instruments, a legendary runner from the Inca period, professional crying women, and a flirtatious love song sung by “romanceros.”

Dora Pejačević

Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) was born in Budapest, but grew up in her ancestral Croatia. Her mother was a Hungarian countess, “a woman of great beauty who was a trained singer, played the piano and was a fine amateur painter.” Dora was educated by a private English governess, and she was fluent in several languages. She taught herself to play the piano and her early compositions paved the way for her study abroad. She attended the Croatian Music Institute in Zagreb, and also took lessons in Dresden and in Munich. However, in musical terms she was largely self-taught, “which is remarkable considering the inventiveness, rich brilliance and enduring quality of her compositions.” She composed her first orchestral work, a piano concerto in 1913, and part of her Symphony was first presented in Vienna in 1918, and subsequently performed in full in Dresden in 1920. Dora married the military officer Ottomar von Lumbe in 1921, and three months before the birth of their son Theo she wrote, “I hope that our child should become a true, open and great human being—prepare its way for it, never prevent it from knowing in life that suffering ennobles the soul because only in that way can one become a human being.” Her portentous words sadly proofed prophetic, as Dora died in Munich in 1923, at the incredibly young age of 38.

Pejačević Hall

Her compositions including songs, piano works, chamber music and several works for large orchestra follow a late Romantic idiom, “enriched with Impressionist harmonies and lush orchestral colours.” In her music Pejačević always strove to break free “from drawing-room mannerisms and conventions,” and she introduced the orchestral song into Croatian music. “Her work concurred with the modernist movement in literature and the secession in the visual arts; without breaking new ground she helped to bring a new range of expression into the traditional musical language.” Much of her music has yet to be published and recorded, but the Croatian Music Information Center holds her 57 known compositions as a single collection, and they have published a number of her larger scores. Indeed, there is newly-found interest in Pejačević as her life became the subject of the fictionalized film “Countess Dora.”

Beegie Adair Trio - Autumn Leaves

Eric Clapton - Over the Rainbow (with lyrics)

Sunday, September 4, 2022

Saturday, September 3, 2022

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and His Circle of Friends

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Pyotr Jurgenson

To his extensive entourage, fellow colleagues, and large circle of friends, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was “a sweet and caring man, full of excellent manners.” Yet in his own words, the composer considered himself almost antisocial. “By nature, I am a savage,” he writes, “every new acquaintance, every fresh contract with strangers has been the source of acute moral suffering.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (ca. 1888)

For a composer seeking public recognition and an artistic career, this turned out to be a bit of a problem. Only his closest friends were aware of his state of mind, and that included Tchaikovsky’s principal music publisher Pyotr Jurgenson (1836-1904), to whom he writes, “I feel at my best when I am alone.” Jurgenson had initially provided financial assistance to Tchaikovsky’s fledgling career by giving him various commissions and assignments. And in 1867 he published Tchaikovsky’s Opus 1, and in the end acquired the rights to publish the composer’s works in Russia and throughout the world. In essence, Jurgenson managed Tchaikovsky’s business affairs, and he recognized the importance of preserving the manuscripts of the composer. He also proved to be a highly supportive friend in the wake of Tchaikovsky’s failed marriage.

Herman Laroche

Herman Laroche (1845-1904) was an incredible musical talent. He wrote his first compositions by the age of ten, and by age twelve he was invited to enroll at the newly found Saint Petersburg Conservatory. He first met Tchaikovsky in 1862, and the two students became lifelong friends. Tchaikovsky found in Laroche an unofficial guide and mentor, while Laroche became the first critic of Tchaikovsky’s school compositions. Initially, he seemed to have been pessimistic about Tchaikovsky’s composing prospects, but Tchaikovsky placed the greatest confidence in his judgment. After graduation, both worked as professors at the Moscow Conservatory, but Laroche increasingly turned to music criticism. He contributed a good many articles to various publications, and after the composer’s death, Laroche wrote a number of valuable studies and memoires of his friend. Laroche was somewhat inexperienced in earthly matters, which not only amused Tchaikovsky, but also gave him the opportunity of helping and advising his friend. When Laroche’s second marriage failed, he suffered a creative crisis. During this period Tchaikovsky assisted him with his articles, and he orchestrated sketches for Laroche’s Overture-Fantasia in 1888.

Emiliya Pavlovskaya

Emiliya Pavlovskaya (1853-1935) performed on a number of European and Russian operatic stages, and she had long-term contracts at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow and the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. Tchaikovsky considered her an exceptionally talented, clever, and gifted singer, and he was a frequent guest at Pavlovskaya’s house. In her memoirs, she recalled a conversation in May 1885. “Pyotr Ilyich once came to me,” she writes, “frightfully worked up, and told me that he had just been to see Anton Rubinstein and had come straight to me to ask my advice. He had been invited to become director of the Moscow Conservatory and Rubinstein was trying to persuade him to accept this offer; Pyotr Ilyich was terribly worried and didn’t know what to do. I resolutely set about dissuading him from accepting the offer, as I knew very well his forgetfulness, his soft character, his nervousness, and the complete absence of any administrative streak in him.” Following this conversation, Tchaikovsky apparently sat down immediately to write a telegram to Rubinstein declining the offer. The friendship soured when Tchaikovsky’s opera The Enchantress failed because Pavlovskaya had given an unsatisfactory performance as the heroine Nastasya. Pavlovskaya accepted blame for the fiasco and suggested that Tchaikovsky pick another Nastasya. And she was aware that Tchaikovsky was angry at her, writing, “Something has happened between us (on your part), some dark cloud has come over me… I don’t understand… but I can feel it, and it hurts me very, very much.”

Ivan Klimenko

The composer and critic Alexander Serov hosted a popular salon in Saint Petersburg in the early 1860s, and it was at one of these gatherings that Tchaikovsky met the architect and amateur musician Ivan Klimenko (1841-1914). Their friendship became particularly close when Klimenko moved to Moscow and overlapped with the composer between 1869 and 1872. The relationship was not only highly intimate it also served as a sounding board for musical matters. Tchaikovsky writes, “As regards to ambition, I must tell you that I have certainly not been flattered of late. My songs were praised by Laroche, but Cui and Balakirev don’t think highly of them… My overture, Romeo and Juliet, had hardly any success here and has remained quite unnoticed. I thought a great deal about you that night. After the concert we supped, and no one said a single word about the overture during the evening. And yet I yearned so for appreciation and kindness! Yes, I thought a great deal about you, and of your encouraging sympathy.” At the request of Modest Tchaikovsky, Klimenko would eventually write a highly intimate account of his relationship with Pyotr.

Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda von Meck (1831-1894) gave birth to 18 children, and when her husband Karl von Meck unexpectedly died, she inherited a great deal of money. With her husband’s considerable fortune at her disposal, she indulged her musical passions and generously supported the Russian Musical Society. Through Yosif Kotek she came in contact with Tchaikovsky’s compositions, and the ensuing correspondence lasted almost fourteen years. Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck never met personally, but the relationship provided moral support and a regular financial allowance to the composer. Von Meck was a highly educated woman who had vast knowledge of literature, history, and philosophy, and she spoke a number of foreign languages. They corresponded on equal terms, without condescension or social snobbery. Tchaikovsky called her his “best friend,” and the platonic relationship with a great composer must have satisfied an important inner need in her. Through her generous financial support, Tchaikovsky was able to focus exclusively on his creative work, and he dedicated three of his compositions to her. Because of the private nature of their relationship even dedications had to be done secretly, so the set of pieces for violin and piano entitled Souvenir d’un lieu cher simply carry the inscription “dedicated to B,” identifying his benefactress’s estate at Brailov.

Nikolay Hubert

Nikolay Hubert (1840-1888) was a fine pianist who entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory at the age of 23. He studied orchestration with Anton Rubinstein, and he formed a lifelong friendship with Tchaikovsky, a fellow student. After graduating he held a couple of temporary jobs, but in 1870 became professor of music theory at the Moscow Conservatory. He was the only witness to the disastrous occasion when Tchaikovsky played his First Piano Concerto to Nikolay Rubinstein. Hubert replaced Laroche as the pre-eminent music critic at the journals Contemporary Chronicle and the Moscow Register during the 1870s, and Tchaikovsky was always ready to assist with writing one or the other articles. Hubert and his wife Aleksandra were among Tchaikovsky’s closest friends, and they made piano transcriptions of many of the composer’s orchestral works. In 1872, Tchaikovsky dedicated one of the Six Romances, Op. 16, to his close friend.