Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric Chopin suffered from serious and chronic health problems throughout his short life. Already in his teens, Chopin suffered from frequent respiratory problems that included coughing, headaches, and the swelling of the cervical lymph glands. Biographers and doctors have detailed numerous episodes of bronchitis and laryngitis, and he appears to have caught a bout of influenza in Paris in 1837. Adding to this were several periods of severe depression, as he complained of “hopelessness, apathy, and sleeplessness.” It has been reported that he frequently had to “be carried to bed after playing the piano for a long time.” His doctor, Paul-Léon-Marie Gaubert assured him that he was not suffering from tuberculosis, but that might simply have been some friendly misdirection. As Chopin’s health deteriorated after 1840, he was described “as pale, thin, looking ill, and weighing only 45 kilograms.”

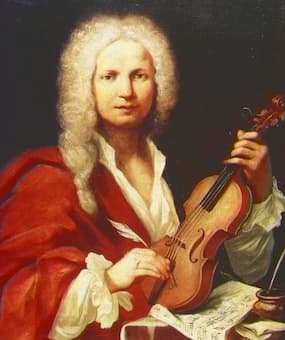

Delacroix: Chopin, 1838

When Chopin traveled to England during the winter of 1847 his health had only deceptively improved. He was habitually short of breath and lacked energy, and instead of performing a series of concerts, as he had hoped, he spent most of his time in bed. A side trip to Scotland in April 1848 only made matters worse, and he returned to Paris in a seriously weakened state in November of that year. An army of doctors tended to his physical ailments, including cough, fever, painful wrists and ankles, hemoptysis, hematemesis and ankle edema. Chopin’s condition deteriorated further at the beginning of October 1849, and he died on the morning of 17 October 1849 “after having been unconscious for 24 hours.” The death certificate listed tuberculosis in the lungs and larynx as the official cause. Dr. Jean Cruveilhier, considered one of the foremost medical experts, performed the autopsy, but his report has never been found.

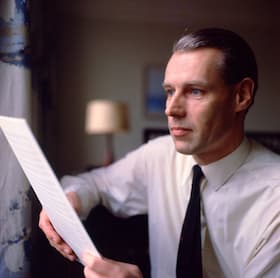

Frédéric Chopin, 1849

Despite his constant health struggles, “Chopin reached a new plateau of creative achievement, marked by an eloquent simplicity which severely excludes the extraneous and the gratuitously ornamental.” These last works, however, did cause Chopin and assorted editors and publishers some difficulties. Chopin generally bypassed the sketching process and proceeded directly from the piano to the engraver’s manuscript. As such, dealing with Chopin’s posthumous works—some I am featuring in this article—turned out to be a rather complex undertaking. Chopin’s posthumous publications of 1855 and 1869 featured opp. 66-74. The edition was prepared by Julian Fontana for Meissonier and A.M. Schlesinger. Theses posthumous works resurface in the two earliest collected editions of Chopin’s work. Fétis edited one for Schonenberger in 1860, and the other was edited by Chopin’s Norwegian student Tellefsen and published by Richault, also in 1860. These two editions are markedly different because “the first assumed an editorial license, an implicit belief that the editor knows best, while the second attempted to recover a living Chopin performance tradition, even if this involved departing from the sources.”

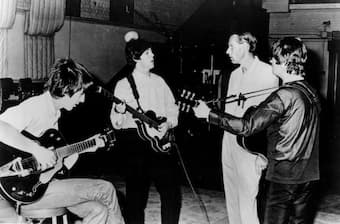

Chopin on his deathbed

The majority of Chopin editions published in the late 19th and early 20th century followed these two opposing philosophies. Furthermore, the late 19th century cultivated several different images of Chopin. In France, Chopin was considered the poet of the piano, who “disclosed his suffering through music.” His music was placed entirely within an intimate performance context, and his art for nuance, sophistication and refinement was considered a model to be followed. In Germany, meanwhile, Chopin was freed from the Parisian salon and elevated to a composer of classical music. For Russian composers, Chopin was first and foremost a Slavonic composer, and England “largely domesticated his compositions… reducing his music to ‘drawing-room trifles,” and ‘pearls’.” Chopin’s music was, for the late 19th century, “an intimate communication, an agent for cultural and even political propaganda, and a commodity.”