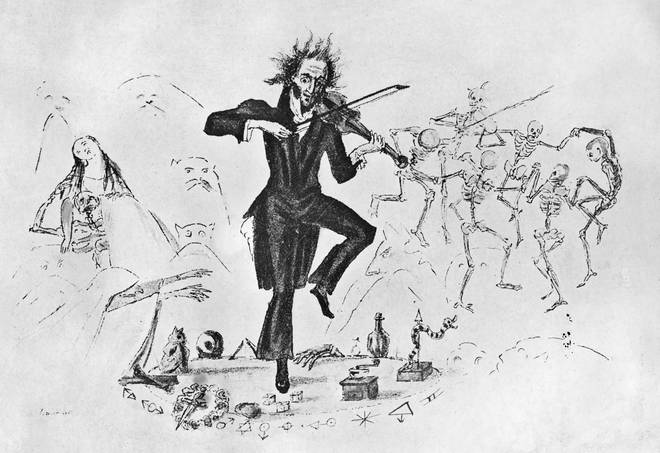

Puccini is one of the most beloved of all opera composers La Bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly and Turandot still play to packed opera houses the world over. Generally snubbed by the critics, Puccini was a serial adulterer whose greatest passions (apart from women) were massacring the local duck population and hurtling around in high-speed cars and boats. Yet behind the macho image, he was a creative artist of profound sensitivity and dramatic flair. This essential music companion provides a compelling overview of the constant tension between Puccini's indulgent personal life, his status as an international celebrity and his excruciatingly high standards as a composer.

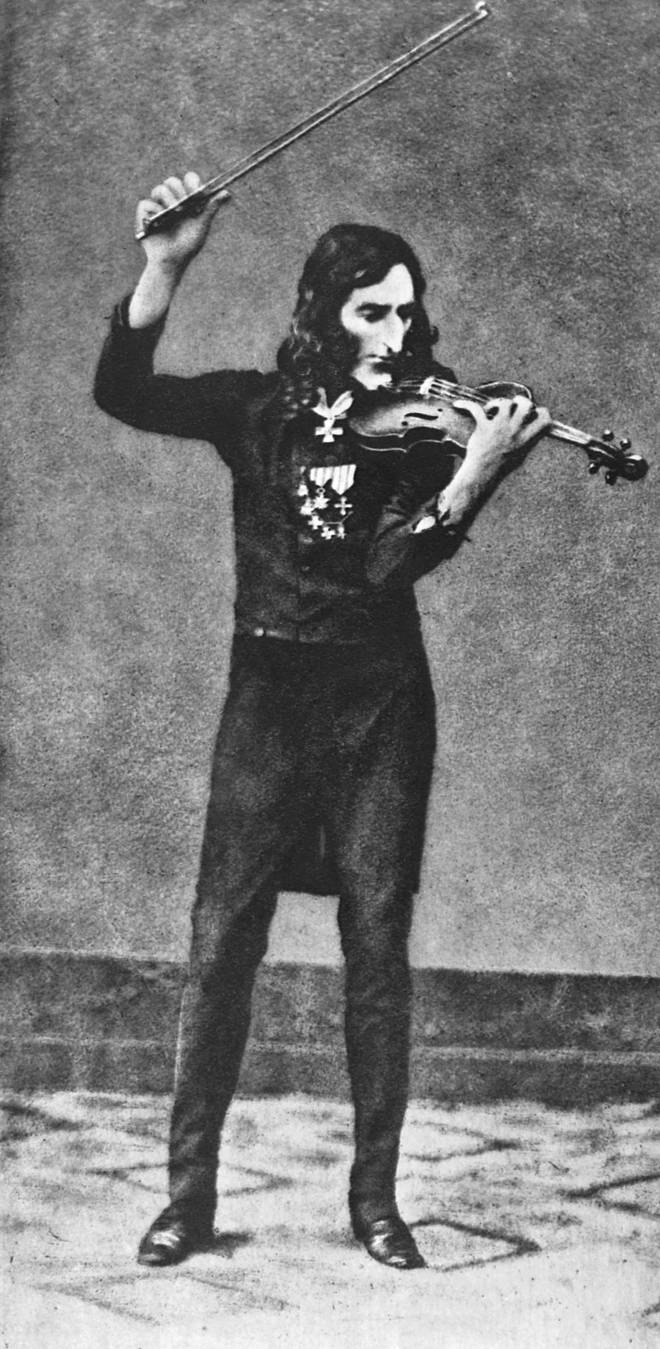

Italian composer Giacomo Puccini started the operatic trend toward realism with popular works such as 'La Bohème' and 'Madama Butterfly.'

Who Was Giacomo Puccini?

Italian composer Giacomo Puccini started the operatic trend toward realism with his popular works, which are among the most often performed in opera history. But the fame and fortune that came with such successes as La Bohème, Madama Butterfly and Tosca were complicated by an often-troubled personal life. Puccini died of post-operative shock on November 29, 1924.

Early Life

Giacomo Puccini was born on December 22, 1858, in Lucca, Italy, where since the 1730s his family had been tightly interwoven with the musical life of the city, providing five generations of organists and composers to the Cathedral of San Martino, Lucca’s religious heart. It was therefore taken for granted that Puccini would carry on this legacy, succeeding his father, Michele, in the role first held by his great-great grandfather. However, in 1864 Michele passed away when Puccini was just 5 years old, and so the position was held for him by the church in anticipation of his eventual coming of age.

But the young Puccini was disinterested in music and was a generally poor student, and for a time it seemed that the Puccini musical dynasty would end with Michele. Puccini’s mother, Albina, believed otherwise and found him a tutor at the local music school. His education was also subsidized by the city, and over time, Puccini started to show progress. By the age of 14 he had become the church organist and was beginning to write his first musical compositions as well. But Puccini discovered his true calling in 1876, when he and one of his brothers walked nearly 20 miles to the nearby city of Pisa to attend a production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. The experience planted in Puccini the seeds of what would become a long and lucrative career in opera.

From Milan to 'Manon'

Motivated by his newfound passion, Puccini threw himself into his studies and in 1880 gained admission to the Milan Conservatory, where he received instruction from noted composers. He graduated from the school in 1883, submitting the instrumental composition Capriccio sinfonico as his exit piece. His first attempt at opera came later that year, when he composed the one-act La villi for a local competition. Although it was snubbed by the judges, the work won itself a small group of admirers, who ultimately funded its production.

Premiering at the Teatro dal Verme in Milan in May 1884, La villi was well received by the audience. But more importantly, it caught the attention of the music publisher Giulio Ricordi, who acquired the rights to the piece and commissioned Puccini to compose a new opera for La Scala, one of the most important opera houses in the country. Performed there in 1889, Edgar was an utter failure. But Ricordi’s faith in Puccini’s talents remained unshakable, and he continued to support the composer financially as he set to work on his next composition.

Blaming the failure of Edgar on its weak libretto (the lyrical portion of an opera), Puccini set out to find a strong story on which to base his new work. He decided on an 18th-century French novel about a tragic love affair and collaborated with the librettists Guiseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica on its adaption. Manon Lescaut premiered in Turin on February 2, 1893, to great acclaim. Before the year was out, it was performed at opera houses in Germany, Russia, Brazil and Argentina as well, and the resulting royalties paid the 35-year-old Puccini quite handsomely. Despite this overwhelming success, however, his best was still to come.

The Big Three: 'La Bohème' and 'Madama Butterfly'

With their accessible melodies, exotic subject matter and realistic action, Puccini’s next three compositions are considered to be his most important; over time they would become the most widely performed in opera history. The result of another collaboration between Puccini, Giacosa and Illica, the four-act opera La Bohème was premiered in Turin on February 1, 1896, again to great public (if not critical) acclaim. In January 1900, Puccini’s next opera, Tosca, premiered in Rome and was also enthusiastically received by the audience, despite fears that its controversial subject matter (from the novel of the opera’s same name) would draw the public’s ire. Later that year, Puccini attended a production of the David Belasco play Madam Butterfly in New York City and decided that it would be the basis of his next opera. Several years later, on February 17, 1904, Madama Butterfly premiered at La Scala. Though initially criticized for being too long and too similar to Puccini’s other work, Butterfly was later split up into three shorter acts and became more popular in subsequent performances.

His fame widespread, Puccini spent the next few years traveling the world to attend productions of his operas to ensure that they met his high standards. He would continue to work on new compositions as well, but his often-complicated personal life would see to it that one would not be immediately forthcoming for some time.