The right music selection can help you by boosting your mood, lowering your stress, and even improving your mental health.

What genre is the best for this purpose, though?

The science is still coming in, but classical music is an especially promising option.

Here are eight surprising ways that classical music can help you focus and study.

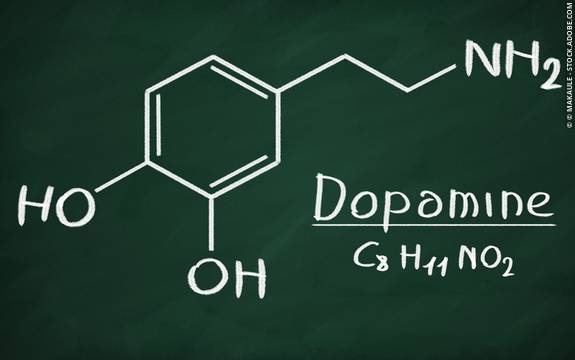

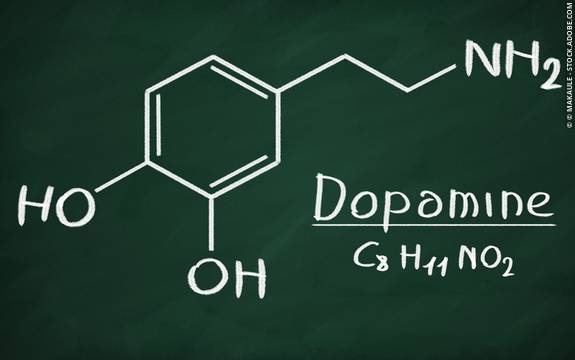

1. Music can alter your brain chemicals in helpful ways.

© psychologistworld.com

When listening to music that you enjoy, your brain releases a neurotransmitter and hormone known as dopamine.

According to the Cleveland Clinic’s website:

Dopamine is known as the “feel-good” hormone. It gives you a sense of pleasure. It also gives you the motivation to do something when you’re feeling pleasure…

If you have the right balance of dopamine, you feel happy, motivated, alert, and focused.

In addition to encouraging the release of dopamine, listening to music can help suppress the production of the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol spikes during stressful situations, and extended exposure to it can lead to anxiety, insomnia, and other symptoms.

Increasing dopamine levels and decreasing cortisol levels can help make it easier for your brain to focus.

2. Music helps us reach a balanced energy state.

Everyone knows how difficult it is to focus when you’re tired…or wired.

There’s a happy middle ground here, and the right kind of music can help you reach it.

Every classical music lover has listened to recordings that have calmed us down, and others that have pumped us up.

Using that fact to our advantage in our listening means that we can impact our energy levels as we’re trying to focus.

3. Music masks distractions.

Even if we manage to stay off our phones while working, there are still distractions all around us.

A dog might be barking down the street. Maybe you’re working in a coffee shop next to a loud espresso machine. Maybe you’re in your dorm or apartment, and you can hear your neighbours talking or fighting.

Even if you can work while these things are going on, just noticing them and anticipating them takes up a portion of your brain’s processing power.

Not only does listening to music help to obscure the most common distractions, it also creates a predictable kind of soundscape that frees up space to focus.

4. Genres with lyrics are distracting…and a lot of classical music doesn’t have them.

© theconversation.com

Many people claim that it’s difficult to concentrate on a task if they’re listening to music with lyrics.

Scientists are still learning about this phenomenon, but one 2023 study suggests that this might be true, depending on the task.

The abstract of “Should We Turn off the Music? Music with Lyrics Interferes with Cognitive Tasks” reads:

Music with lyrics hindered verbal memory, visual memory, and reading comprehension…whereas its negative effect on arithmetic was not credible.

The other genre the scientists tested – hip-hop lo-fi – was an instrumental one.

While listening to lo-fi didn’t improve participants’ performance, it also didn’t hinder it in the way music with lyrics did.

This is a preliminary study, and more research needs to be done about which genres and types of music might be helpful for specific kinds of tasks.

But it’s worth noting that a lot of classical music doesn’t employ singers or lyrics…making it an especially intriguing option for people who are experimenting with using music to improve their concentration.

5. Classical music can impact your brain waves. (Or at least some classical music can.)

According to one study:

The term “brain (or neural) oscillations” refers to the rhythmic and/or repetitive electrical activity generated spontaneously and in response to stimuli by neural tissue in the central nervous system.

(Another term for these oscillations is “brain waves.”)

Alpha waves are a type of brain wave associated with a relaxed but alert frame of mind: perfect for inducing focus.

Some music has been shown to encourage alpha waves.

One study in Rome was recently published in Consciousness and Cognition. It followed thirty participants who listened to Beethoven’s Für Elise and an excerpt from Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos in D-major, KV 448.

According to the researchers:

The results of our study show an increase in the alpha power and MF frequency index of background activity in both adults and in the healthy elderly after listening to the Mozart sonata.

Interestingly, Beethoven’s Für Elise did not elicit the same response, suggesting that not all classical music might be equal when it comes to encouraging alpha waves.

6. The tempo of classical music can encourage a calm heart rate.

© onlymyhealth.com

It can be hard to concentrate if you’re stressed out and have a fast pulse.

One technique to bring a pulse down to resting rate is to listen to music with the pulse rate you’re aiming for.

A healthy resting heart rate can vary widely depending on a person’s age, fitness, and gender, but a standard number to shoot for is around 60 beats per minute.

Interestingly, this is a common tempo for a wide variety of classical music. It’s especially common in slow movements from the Baroque era.

7. The structure of a lot of classical music is very predictable, which enables our brains to focus more easily on other things.

A lot of classical music was composed by using formulas, especially in the Baroque era. These formulas and conventions have to do with tempo, dynamics, and structure generally.

The patterns that make up these formulas mean that the music is just predictable enough to give your brain something to latch onto, without distracting it.

8. Silence can be lonely. Classical music can provide companionship…and make tasks requiring concentration more appealing.

Many people prefer completing overwhelming tasks with supportive company.

Listening to classical music while completing a task can improve your working experience, especially if you are feeling isolated, overwhelmed, or unmotivated.

Most classical music is unamplified and non-electronic, enhancing its human qualities and making listeners feel especially close to the performer.

Conclusion

There is a lot that scientists don’t know about how music affects people’s concentration. Hopefully, more studies will be undertaken in the years to come so that we can understand both its limitations and its power.

But until all of the science is in, one thing is for sure: classical music is one of the most promising genres to experiment with when you’re deciding what music will help you focus.