Robert Redford has died at 89 years old.

It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, September 16, 2025

Robert Redford has died at 89 years old

Monday, September 15, 2025

Sunday, September 14, 2025

Jessica Sanchez sings a tagalog song “Ikaw”

Leonard Cohen - Dance Me to the End of Love (Official Video)

Friday, September 12, 2025

Albinoni and Bach “What I Have Achieved by Industry Anyone Else Can Also Achieve”

Tomaso Albinoni

Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1750) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) were contemporaries, but they never actually met. While Albinoni was at home on various Italian and international operatic stages, Bach never traveled far away from his native community in North-Germany. We do know, however, that Bach did come in contact with the music of various Italian masters, and that his scholarly confrontation with these new styles decisively shaped his musical language and understanding. A scholar has suggested that “the best outside movements of Albinoni’s later concertos are remarkably like some of those by Bach, who benefited from the study of these works.” That similarity is found in some interesting variants of the common Albinoni approach to ritornello form, one, which Bach, took over into his works. Several movements from Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos “show clear signs of having been written under the influence of the concertos for one and two oboes of Albinoni’s Opus VII.”

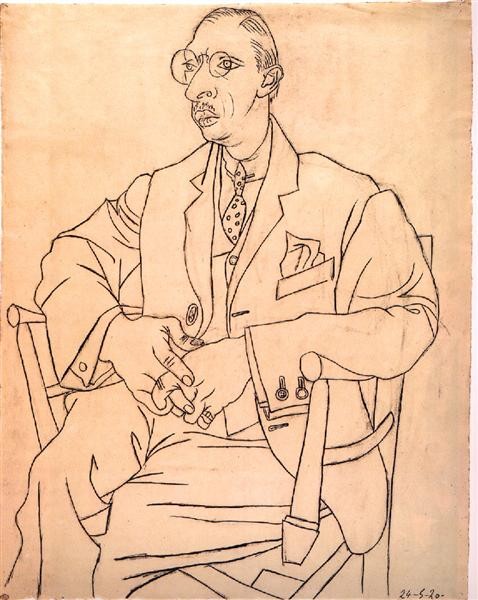

The young Bach, Weimar, 1715

While we can certainly hear some of the similarities of structure and tonal organization, how did Bach actually got his hands on the Albinoni scores? Two possible scenarios have been suggested. In the autumn of 1717 Bach traveled from Weimar to Dresden. The crown prince of Saxony had recently returned from an extended journey to Italy, having spent almost one year in Venice. One of the musicians from the Dresden Court, Johann Georg Pisendel had accompanied the crown prince on his travels, and he became good friends with Vivaldi and Albinoni. Pisendel did make copies of Albinoni’s Op. VII and brought the music to Dresden. We might rightfully assume that the oboist of the Dresden Hofkapelle, Johann Christinan Richter took a close interest in these oboe concertos, and “Bach could certainly have come in contact with certain Albinoni concertos during his stay in Dresden.”

Albinoni’s Concertos Op. VII

We don’t know if Bach made copies of the works he encountered in Dresden, but we do know that he made a trip to Berlin 1719. He was on a mission to take delivery of a new harpsichord for court at Cöthen, and he spent much time and money buying the latest chamber works in circulation. “Albinoni’s Opus VII concertos may well have been among many acquisitions of printed music. There is no concrete source evidence, but it seems unlikely that Bach came in contact with the Albinoni collection much before the fall of 1717, given the collection’s relatively recent publication date and the rate of transmission of Amsterdam prints to Central Europe.”

The mature concertos of Albinoni “were an important factor in Bach’s approach to the genre throughout the decade of the 1720s. Albinoni was certainly not the only influence on Bach’s concertos from this period, but he must be counted among the chief influences. His extended opening ritornellos, his use of formal and structural elements derived from an Italianate vocal style of writing for the soloist seems to have greatly appealed to Bach.”

J.S. Bach: Fugue in C major, BWV 946

J.S. Bach: Fugue in A major, BWV 950

While the close connection between Albinoni’s Op. VII and Bach’s Brandenburg’s rely on careful stylistic, formal and harmonic analysis, an immediate connection is found in four keyboard fugues with subjects taken from Albinoni’s Op. 1. In BWV 946, 950, 951, 951a we find Bach mastering a new style and maturing as a composer. While some scholars find “facile note-spinning and pointless harmonic meandering among other weaknesses,” others “give Bach credit for tackling rhythmically difficult subjects in a variety of two-, three-, and four-part textures during his teenage years.” In BWV 950, Bach quotes directly from the Albinoni original at two points beyond the subject itself. However, Bach does not merely quote the passages but expands and transforms them to become pillars of the formal structure. A critic writes, “Bach’s scholarly engagement with Albinoni taught him to bring the fugue to a convincing conclusion without a thematically irrelevant coda.”

Musicians and Artists: Stravinsky and Matisse

by Maureen Buja

The Nightingale Collaboration

Even though they were contemporaries, Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) and Henri Matisse (1869–1954) are rarely regarded together. In 1925, however, the two collaborated on a project for the Ballets Russes on a ballet version of Stravinsky’s first opera, The Nightingale, which was given its premiere in Paris on 26 May 1914. The discrepancy between the first act, written in 1908 and still very much by a student of Rimsky-Korsakov, and the second and third acts, written in 1913 and 1914, was a problem.

Pablo Picasso: Igor Stravinsky, 1920 (Paris: Picasso Museum)

Sabine Devieilhe as The Nightingale, 2023 (Paris: Théâtre des Champs-Elysées)

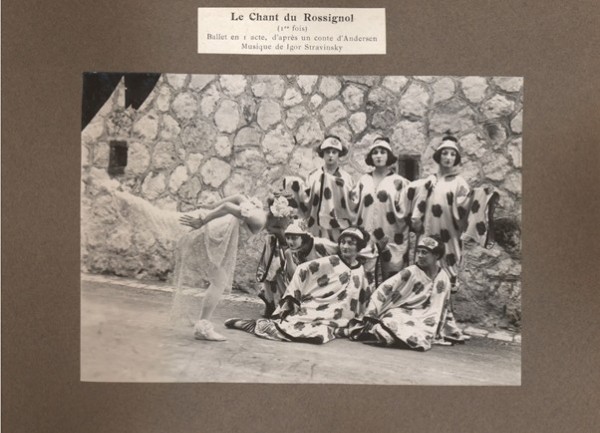

The story comes from Hans Christian Andersen, where a Chinese Emperor is given a live nightingale, which has a song so sweet that hearers weep with its beauty. Emissaries from Japan give the Emperor a mechanical nightingale that delights him. The real nightingale returns to the forest, insulted. Death comes for the Emperor, and the nightingale returns and charms Death. In return for singing for Death, he must return to the Emperor his crown, sword, and standard. Death agrees, and the Emperor comes back to life. The Emperor discards his mechanical bird, and the live bird agrees to sing nightly for the Emperor.

The poème symphonique called Chant du Rossignol also dates from 1914 as a way for Stravinsky to respond to some of Diaghilev’s criticism of the opera. Stravinsky dumped the 1908 first act material and only used the music from Acts II and III for a piece in four movements.

Without the context of opera, the Chinese elements in the work, including pentatonic scales and other exoticisms, would be difficult for the audience to understand. When the poème symphonique received its premiere on 6 December 1919, with Ernst Ansermet leading the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. It was heavily criticised for its dissonance.

Still attempting to rescue the work, Stravinsky turned it into a ballet, written in the early months of 1917 but not staged until after WWI.

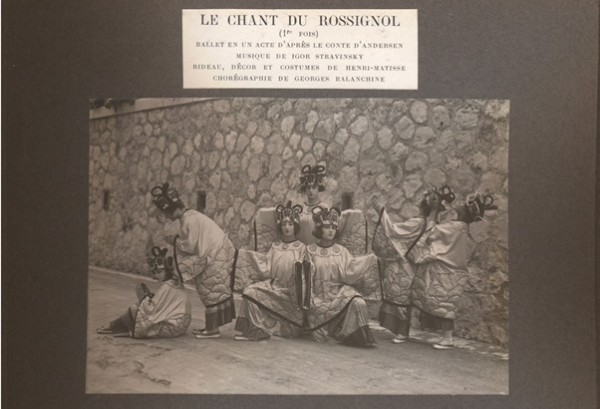

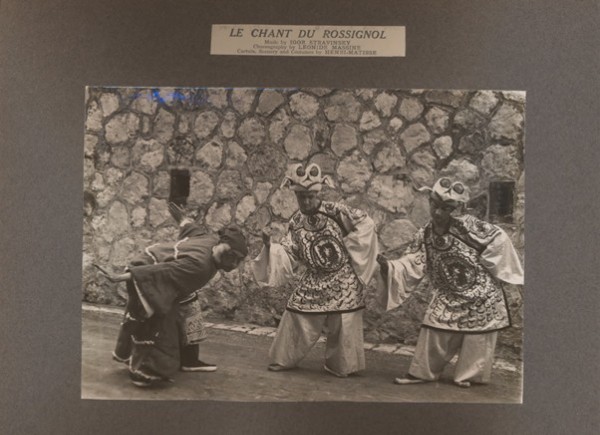

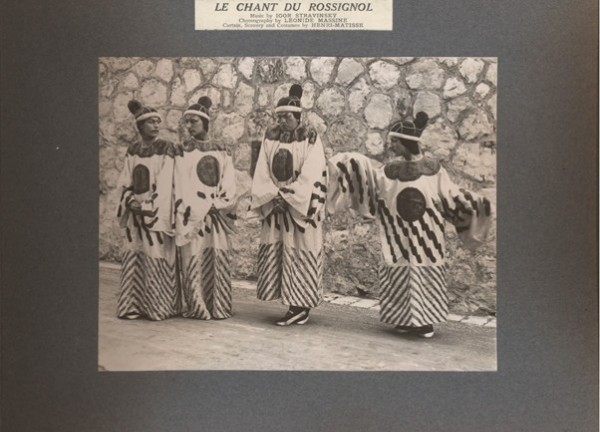

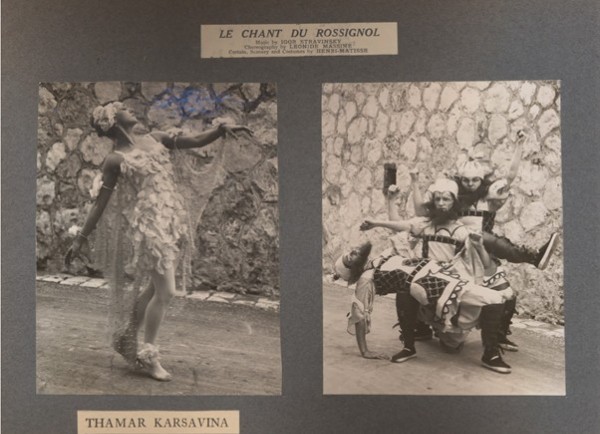

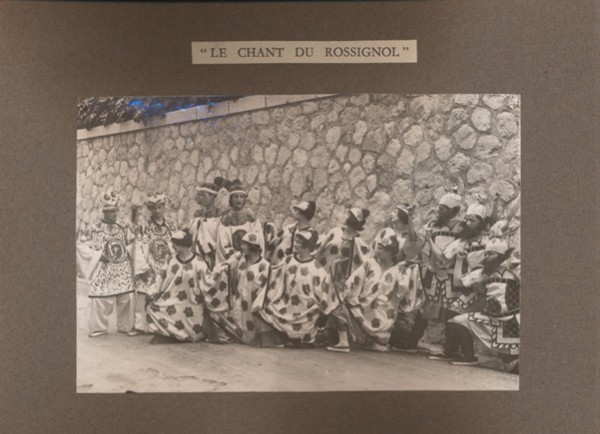

The ballet received its premiere on 2 February 1920 with choreography by Leonid Massine and designed by Henri Matisse.

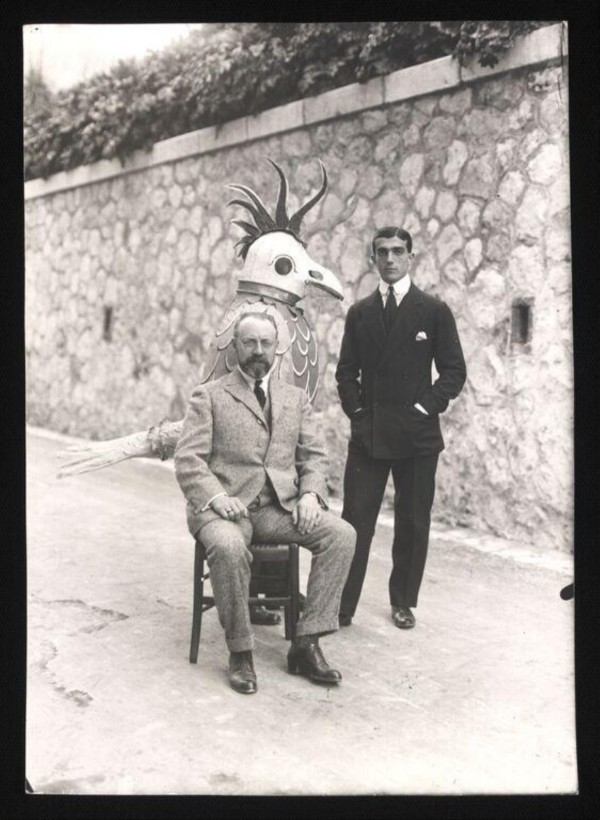

Henri Matisse (seated) and Léonide Massine shown with the mechanical nightingale, 1920

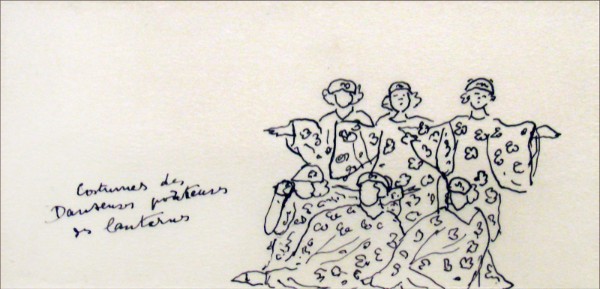

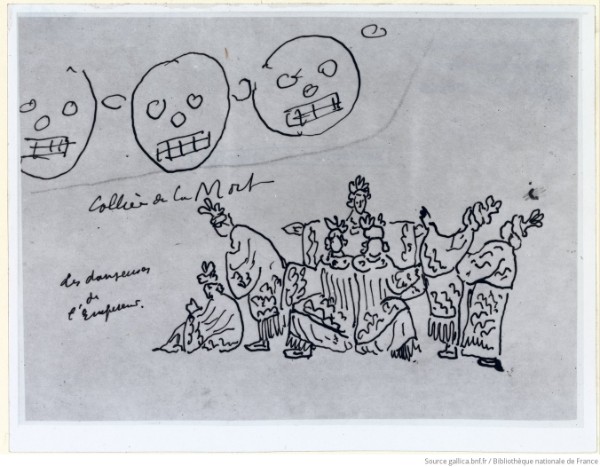

Matisse’s drawings for the production put the Chinese elements to the fore.

Matisse: Costumes for the dancers

Matisse: Costumes for the dancers and the Emperor (Gallica: btv1b7002923m)

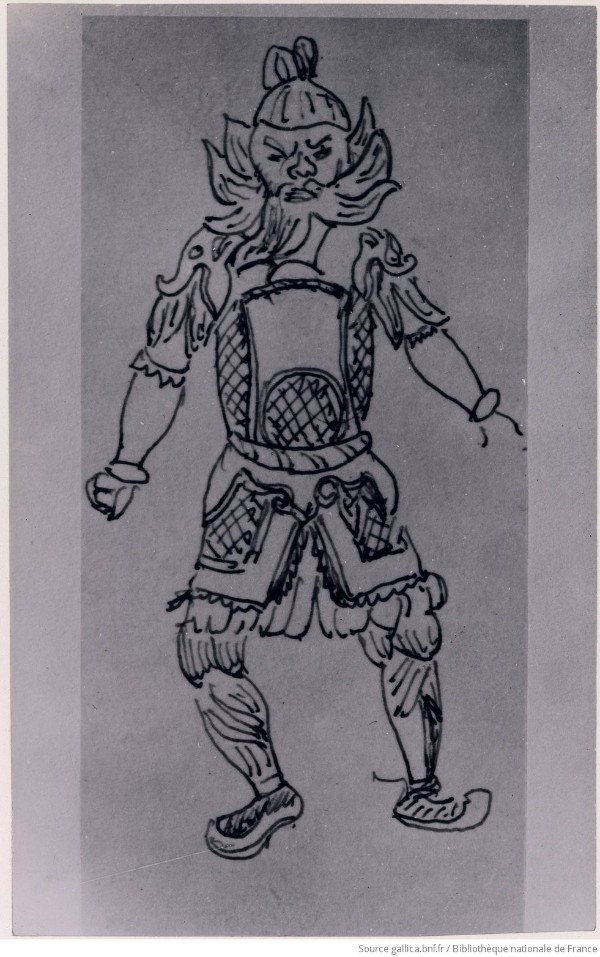

Warrior’s costume (Gallica: btv1b7002916g)

Serge Leonovich Grigoriev (1883–1968) was the regisseur of the Ballets Russes from 1909 through the 1920s, and then, after the disbanding of the company with Diaghilev’s death in 1929, joined Colonel de Basil’s Ballet Russe in 1932, remaining with that company until 1948. The position of regisseur is critical to any company – functions as not only the director and the stage manager but also the choreographic reference point, and company memory. His phenomenal memory is what made Diaghilev’s ballets live on through the decades.

The Library of Congress holds Serge Leonovich Grigoriev’s photo album with examples of sets and costumes for Pulcinella, Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur, Petrouchka, Zéphire et Flore, Mavra, Le Renard, Les Biches, Les Fâcheux, and Barabau and photographs of Pulcinella, Le Chant du Rossignol, and Les Matelots.

Although they are in black and white, we can get a feeling for Matisse’s designs. Dancing the role of the Nightingale was Tamara Platonovna Karsavina, one of the leading ballerinas in the Russian Imperial Ballet, who was frequently invited to dance with Diaghilev’s company. Her most famous role was that of The Firebird in Stravinsky’s ballet for Diaghilev.

Image 7 (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

Image 8 (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

Image 9 (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

Image 10 with Tamara Karsavina as The Nightingale (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

Image 11 with Tamara Karsavina (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

Image 12 (Library of Congress, Serge Grigoriev’s photo album/scrapbook, https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/ihas.200156317)

There is one photograph of the stage with Matisse’s decorations and costumes.

Henri Manuel: Photograph of the stage, designs by Matisse, 1920 (Gallica: btv1b7002909b)

The dilemma for Stravinsky was that he thought the music was best heard in the concert hall, where it receives a focused hearing, rather than on the ballet stage, where the dancers also compete for attention.