It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, June 11, 2025

IL DIVO - Adagio (Live Video)

My Way - Domingo x Carreras x Dimash x HAUSER | Virtuosos 2025

/ virtuosos_talent_show

/ virtuosos_talent_show

/ virtuosostalentshow

/ virtuosostalentshow

/ virtuosostalentshow

/ virtuosostalentshow

/ virtuosostalent

#virtuosos #futureofclassicalmusic

Music & Lyrics: Claude François, Jacques Revaux

English words by Paul Anka

Arranged for Virtuosos by Sergio Kuhlmann

Performed by Plácido Domingo, José Carreras, Dimash Qudaibergen, HAUSER, Concerto Budapest Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Eugene Kohn

Producer: Mariann Peller

Directed by Imre Szabo-Stein

Editor: Attila Lecza

Special thanks: Veronica Bocelli, jury member of Virtuosos

Produced by Virtuosos Holding Ltd.

Virtuosos is a classical music talent show with a unique format, focusing on discovering young classical talent and then giving the talented youngsters a chance to develop and progress in a way that few others have.

Producer: Mariann Peller

/ virtuosostalent

#virtuosos #futureofclassicalmusic

Music & Lyrics: Claude François, Jacques Revaux

English words by Paul Anka

Arranged for Virtuosos by Sergio Kuhlmann

Performed by Plácido Domingo, José Carreras, Dimash Qudaibergen, HAUSER, Concerto Budapest Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Eugene Kohn

Producer: Mariann Peller

Directed by Imre Szabo-Stein

Editor: Attila Lecza

Special thanks: Veronica Bocelli, jury member of Virtuosos

Produced by Virtuosos Holding Ltd.

Virtuosos is a classical music talent show with a unique format, focusing on discovering young classical talent and then giving the talented youngsters a chance to develop and progress in a way that few others have.

Producer: Mariann PellerThis beautiful flashmob in Paris will give you goosebumps.

Friday, June 6, 2025

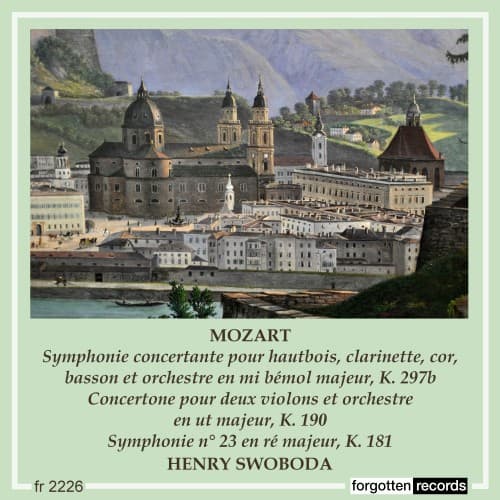

Lost and Recreated: Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, K. 287b

by Maureen Buja

In February 1778, Leopold Mozart told his son to go to Paris with his mother, and the pair arrived in the capital city in March 1778. He immediately started to set up his musical networks and wrote to his father about his activities: he was writing music for choruses for a Miserere by Holzbauer and wrote a Sinfonia Concertante for an ensemble of flute, oboe, bassoon, and horn. However, no such work has even been found.

Croce: Mozart Family Portait (detail), 1781

The sinfonia concertante has a very limited life. It was a successor to the Baroque Concerto Grosso but written for a group of soloists and orchestra. Each soloist has its own prominent role, but at the same time, each soloist is part of the orchestral ensemble. It fell out of use as a genre in the Romantic era but was taken up again in the 20th century by composers such as George Enescu and William Walton.

What we know now as the Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major (K. 297b) is scored for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn. Is this the same work Mozart was referring to in his letter to his father, or something that was just slipped into Mozart’s catalogue because it seemed to fit the bill?

The work came into the repertoire in 1869, and it took nearly a century for it to be questioned. The Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major was considered to be fully by Mozart until 1964, when the editors of the New Mozart Edition decided to banish it to the list of ‘dubious and spurious works’. This is not uncommon, particularly with famous composers such as Mozart – many later composers were more than happy to have their works circulating (and earning royalties) under another’s more famous name. The number of spurious works by Pergolesi is astonishing in its breadth, for example.

Without a manuscript in Mozart’s hand, the question of whose work this might be broadens considerably. Scholars in the 1960s wondered if, perhaps, the solo work was Mozart’s, and the orchestra accompaniment might be by another hand.

The only known source for the work was a copyist’s manuscript from the mid-19th century. When scholars started looking more closely at the piece, however, some problems quickly emerged. When the instrumental writing of the Sinfonia Concertante was compared to known Mozart works, the solo instruments had anomalous disparities from the norm in terms of range (tessitura). The orchestral accompaniment is more like writing from the early 19th century rather than the mid-18th century. The only known source (the copyist’s manuscript ) was prepared for the Mozart biographer Otto Jahn by one of his copyists and doesn’t have any composer’s name on it – the theory is that Jahn’s copyist had a set of the solo parts (flute, oboe, bassoon, and horn) and made his reconstruction updating the instrumentation (oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn) and added the missing orchestral accompaniment.

It is thought that Mozart’s original score was written for four instrumentalists, 3 from Mannheim, who were in Paris when Mozart was there: flautist Johann Wendling, oboist Friedrich Ramm, and bassoonist Georg Ritter from Mannheim, plus the horn player Johann Stich (known as Giovanni Punto). However, there was no Paris performance, and the score vanished. Mozart suspected local intrigue was involved in silencing his work. The work was commissioned by Joseph Legros for performance at his Concerts Spirituels series. However, the composer Giuseppe Cambini interfered, and the performance never occurred. Although not well-known today, Cambini was extremely active in Paris from the early 1770s – by 1800, some 600 instrumental works had been published under his name, and he had symphonies concertantes performed at the Concert Spirituel starting in 1773.

What has intrigued scholars and performers alike is the fact that the work doesn’t show Mozart at his best, but has enough of a ‘whiff’ of Mozart about it to indicate that he may have been involved somehow with the surviving copyist’s score. The problem, of course, is that this is the only work like that that Mozart wrote, and the difficulty of setting up a definition of ‘normal’ on a unique work is almost insurmountable.

Authenticity aside, performers welcomed a ‘new’ work by Mozart and the work has found a ready audience in the modern age.

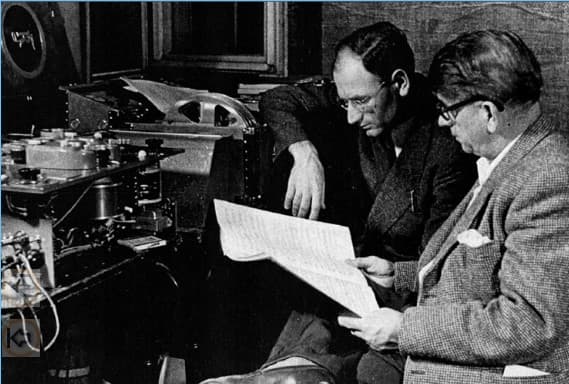

Henry Swoboda at Westminster Records with the pianist and producer Karl Welleitner

This recording was made in January 1950 by an ensemble of soloists from the Vienna Philharmonic and the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera, conducted by Henry Swoboda. Czech conductor Swoboda (1897–1990) studied in Prague and was conductor of the Prague Opera (1921–1923) and the Düsseldorf Opera before emigrating to the US in 1939. In New York, he was the music director for two recording companies (Concert Hall and Westminster) and also led the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra (1962–1964) before returning to Europe to live in Switzerland.

Performed by

Henry Swoboda

The Vienna Philharmonic and the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera

Recorded in 1950

Official Website

Test Your Music Knowledge: How Many of 10 Masterworks by Composers in Their 80s Have You Heard?

by Bruce Robinson

Recently, I heard a superb premiere of music by an 87-year-old composer. I wondered how many composers in their 80s have maintained similar creativity. To my surprise—and delight, as I’m in my 70s—I found ten. The music, much of it rarely performed, will exceed your expectations.

Count the pieces you’ve heard before and check your number against our scale at the end. And enjoy the music!

1. Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672): Schwanengesang

Heinrich Schütz

Heinrich Schütz is usually considered the most important German composer before Bach, celebrated for bringing the Italian style he learned from Giovanni Gabrieli in Venice to Germany. At a time when the average lifespan was 36, he lived to 86. Finally retired after writing more than 500 compositions, he wrote his Schwanengesang (Swan Song) in 1671. This monumental work consists of 11 motets based on Psalm 119, a twelfth motet on Psalm 100 with the Magnificat (My soul magnifies the Lord) and a thirteenth motet on the Nunc Dimittis or Song of Simeon (Lord, let your servant go in peace). The style consists of Netherlands-style modal polyphony with dissonant text-painting, often with two choirs for antiphonal glory in the Venetian style. This excellent recording by Musica Fiata doubles some voices with cornetti, violins or trombones, as Schütz would have done.

2. Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767): The Day of Judgment

Georg Philipp Telemann

No composer has been more prolific than Telemann, with his more than 3,000 compositions. When he became music director of five churches in Hamburg in 1721, Telemann also began producing public concerts. At the age of 81, Telemann composed his oratorio The Day of Judgment for such a public concert. Advertised as a “poem for singing with strong emotions,” its libretto laid out four “contemplations” for its main sections: the proclamation of the Last Judgment, a portrayal of the godless, the horror of the Judgment and the happiness of those in heaven. A closing chorale soothes the listener following the drama of the performance.

3. Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764): Les Boréades

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Rameau became well-known in his 40s for his writings on music theory. At 50 Hippolyte et Aricie established his reputation in opera, and he devoted the rest of his life to that medium. In 1763, his last tragédie en musique, Les Boréades, had been copied and even placed on music stands for rehearsal. Mysteriously, it was never performed. Was it too difficult rhythmically for the musicians? We do not know. The score was subsequently lost and rediscovered, then staged at last in 1982 at the Aix-en-Provence Festival with John Eliot Gardiner conducting, creating a sensation. The music features vibrant dances, pre-Classic melody, a chaotic tempest and gala choruses.

4. Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901): Te Deum from Four Sacred Pieces (Quattro Pezzi Sacri)

Giuseppe Verdi

At the age of 79, Verdi completed his final opera, the splendid comedy Falstaff. Two of his Four Sacred Pieces, Te Deum and Stabat Mater, were completed in his early 80s.

Verdi was not a practicing Catholic, saying that he believed in God but not in priests. The theater sounds through all his sacred music, whether the passages are loud or soft. That said, Verdi requested that the score of Te Deum be buried with him.

Te Deum is written for double choir, orchestra and soprano soloist—preferably a boy soprano. The music ranges from apocalyptic climaxes to whispers, often in close succession. The old recording below was conducted by Arturo Toscanini, who knew Verdi so well he consulted with him personally about the score. The performance illustrates Toscanini’s intensity and his constant attention to phrasing.

5. Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921): Clarinet Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op. 167

Camille Saint-Saëns

Saint-Saëns wrote his Clarinet Sonata at 86, in the last year of his life, along with his Bassoon and Oboe Sonatas. The Sonata contains a lyrical first movement, a sprightly scherzo and a virtuosic rondo reminiscent of Carl Maria von Weber. The piece could be described at various times as elegant, nonchalant, and brilliant. The third movement, the heart of the sonata, begins as a dirge and transforms into a vision of paradise.

6. Richard Strauss (1864-1949): Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs)

Richard Strauss

Composed in 1948, Strauss’ Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra are his last completed works. The title as well as the order of the songs was given by Strauss’ editor at Boosey & Hawkes. Set to three poems by Hermann Hesse and one by Joseph von Eichendorff, the songs meditate on the end of life and transfiguration with serenity and acceptance.

Frühling (Spring) rhapsodizes about youth, shimmering with light and an ecstatic line for the soloist. September celebrates an autumn garden, with accompaniment patterns and inner voices sounding like falling leaves. Beim Schlafengehen (Going to Sleep) features a gorgeous violin solo and an ecstatic rising soprano line as the soul ascends. And Im Abendrot (At Sunset) quotes the Transfiguration Theme from Strauss’ own Tod und Verklärung, the music becoming slower and slower to the end.

Renee Fleming – Strauss’ 4 Last Songs –

7. Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971): Requiem Canticles (1966)

Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky’s last completed score of consequence, Requiem Canticles, was played at his funeral in 1971. Although it was written five years before, when he was 83, Stravinsky’s wife, Vera, said, “He and we knew he was writing it for himself.”

Stravinsky called it “the first pocket Requiem,” as it lasts just 15 minutes. He had written a Mass in the 1940s; here he composed only the sections unique to the Mass for the Dead. It begins with a string prelude and ends with a postlude of bells reminiscent of his 1923 ballet Les Noces. An orchestral interlude splits the vocal movements—Exaudi, Dies irae, Tuba mirum, Rex tremendae, Lacrimosa, and Libera me—most of which are represented by a fragment of the text. As with his idol Tchaikovsky, every measure of his music can be danced, and both George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins choreographed Requiem Canticles.

8. Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992): Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà… (Lightning Over the Beyond…)

Olivier Messiaen

The New York Philharmonic requested a short piece from Olivier Messiaen for its 150th anniversary in 1992; Messiaen responded with a 75-minute work of 11 movements scored for 128 instruments, including three ondes Martenot. Messiaen’s last composition took four years to write, 1987-1991, during which he was often in intense pain from back surgery.

Despite its scale, Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà… is transparent in texture and light in temperament. Messiaen’s writing follows its usual methods and themes—modes of limited transposition, palindromic rhythms, ecstatic Christianity and birdsong—in an astonishing array of textures.

9. Pierre Boulez (1925-2016): Dérive 2

Pierre Boulez

Both the story of Dérive 2 (1988-2006/2009) and the music itself are about constant transformation. Boulez dedicated the music to composer Elliott Carter for his 80th birthday in 1988. Boulez continued to expand the score, so Carter only heard the music at the age of 98, in 2006. Even then, Boulez worked on the music another three years, eventually creating 50 minutes of music.

Dérive 1 (1984) was built on a cryptogram, a set of six notes spelling out the last name of the conductor and music patron, Paul Sacher. Six chords were also developed, and Dérive 2 is also built on this framework. 11 instruments continuously play with this material. Textures are pointillistic, layered in rhythm, constantly being transformed through permutation.

10. John Corigliano (1938- ): Tennessee Songs (2025)

John Corigliano

Read about Corigliano’s Tennessee Songs on poems of Tennessee Williams in my recent article. The premiere was on April 2, 2025, in Tucson, Arizona, with soprano Larisa Martinez and her husband, violinist Joshua Bell. No recording is yet available.

How Do You Measure Up?

I’ve heard none of these pieces.

You’re in good company—and about to discover some gems.

I’ve heard one piece.

Excellent! Now go find the other nine.

I’ve heard two pieces.

You’re officially a connoisseur. Or are you just pretending?

I’ve heard three pieces.

You either know your stuff—or got really lucky with a Spotify shuffle.

I’ve heard four pieces.

Where did you do your graduate work? Vienna? Berlin?

I’ve heard five pieces.

Have you considered donating your brain to musicology?

I’ve heard six pieces.

Are you sure you’re not just counting the same piece six times?

I’ve heard seven pieces.

You’ve either conducted an orchestra or are an orchestra.

I’ve heard eight pieces.

You’ve clearly frightened your streaming algorithm.

I’ve heard nine pieces.

Step away from the headphones and touch grass.

I’ve heard all ten.

Pinocchio? Is that you?