It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

Sunday, April 14, 2024

Marschner - Overture: Der Vampyr (The Vampire)

Madonnina dai riccioli d'oro (A. Costanzo - S. Gallizio - B. Garino)

ORCHESTRA ITALIANA BAGUTTI POLKA

Friday, April 12, 2024

Ein Morgen, ein Mittag und ein Abend in Wien - Franz von Suppé

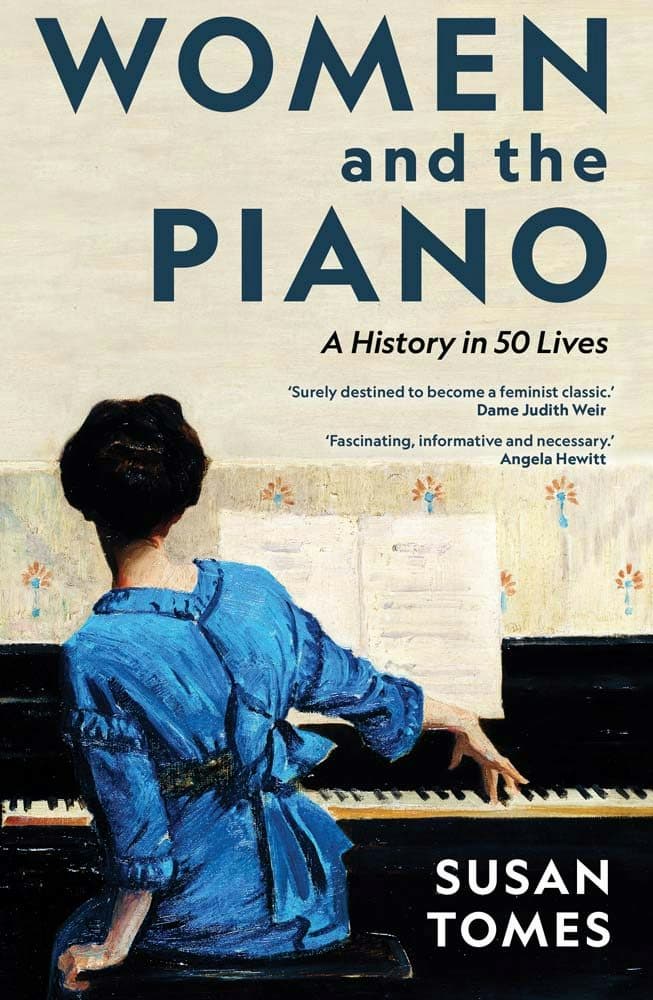

WOMEN AND THE PIANO: A History in 50 Lives - Susan Tomes

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Susan Tomes

Focusing on 50 women pianists – some well-known (Louise Farrenc, Fanny Mendelssohn, Nadia Boulanger, Tatiana Nikolayeva, for example), others less so, or only recently discovered – Tomes traces the lives and music-making of these women across the piano’s history, from the development of the piano in the 18th century to the present day.

As Tomes points out in her introduction, the piano is “an instrument that anyone can play, irrespective of gender”, yet until fairly recently, women pianists and composer-pianists were overlooked, under-represented in concert programmes and recordings, and generally consigned to the background in classical music history.

In some ways, the reasons for this are simple: women pianists lacked access to formal music training, were excluded from performance opportunities, and were even at a disadvantage to men due to the size of the instrument, the piano’s keys being designed for men’s typically larger hands. Additionally, women often had significant obligations to the home and family. And yet, despite these limitations, women continued to play, perform, and compose their own music.

Pioneers, in a number of ways, women pianists carved their own paths within a male-dominated profession. They travelled independently and helped to shape the modern piano concert as we know it today, including playing from memory (Clara Schumann), performing cycles of complete works (Wanda Landoswka/Bach’s Goldberg Variations), premiering new works and reviving historical works, bringing lesser-known and rare repertoire into concert programmes and recordings, and commissioning new music. They were involved in recording, broadcasting, presenting TV programmes about music, creating educational initiatives, devising concert series….and much more – all against a background of, at best half-hearted support, at worst, antagonism, resentment, and open sexism.

These enterprising women, 50 of whom are presented in this book, helped to expand and diversify the profession, gradually debunking the notion that the male approach to a career as a concert pianist was not the only way. These women were not imitators of male pianists but artists in their own right, with their own musical integrity, authority, and identity.

This highly readable, meticulously researched, and elegantly crafted book takes a chronological approach, beginning with French keyboard player Anne-Louise Boyvin d’Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy and ending with Nina Simone, jazz pianist, singer and civil rights activist. For each woman pianist featured, the author gives biographical details, notes their significant performances, recordings or compositions, and demonstrates how they have each contributed to the world of the piano.

The introductory chapters explore some of the reasons why women were sidelined, including social mores and prejudices, and how men became ascendent in the profession. The closing chapters examine where we are today with regard to female musicians, including the effect of equal rights legislation, the rise of piano competitions, shifting attitudes within the profession and audience perceptions, and the influence of teachers. For this section of the book, Susan Tomes spoke to a number of female pianists working today to reveal some surprising insights, and the barriers and limitations which women still face today in a highly competitive global profession.

At a time when the current discourse in classical music – and indeed in society in general – is focused on equality and inclusion, this book is an important, valuable contribution to the debate and a rich celebration of the essential role of women in the history of classical music and the piano in particular.

Playlist: Water Games

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Shipwreck

Each is equally apt: in this piece Ravel brilliantly evokes “the splashing of water and by the musical sounds of fountains, cascades and rivulets” (Ravel) through shimmering figurations, cascading arpeggios and other fluid textures. It’s a masterpiece of Impressionism and was the well-spring for other water-inspired piano music by Ravel, namely Une barque sur l’océan from Miroirs and Ondine from Gaspard de la Nuit.

Fountain in Villa d’Este, Tivoli

But the forerunner of these pieces was undoubtedly Franz Liszt’s Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este, which, like Jeux d’eau, evokes the sparkling play of fountains and the fluidity and brilliance of water. The Villa d’Este boasts an extraordinary system of fountains, with some fifty-one fountains and nymphaeums, 398 spouts, 364 water jets, 64 waterfalls, and 220 basins, fed by 875 metres of canals, channels and cascades, and all working entirely by the force of gravity, without pumps.

Reflections on water

Debussy was also a master of depicting water in music. Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in the Water). Here Debussy imitates not just the sounds of water – droplets and burbles, splashes and raindrops – but also reflections, the pictures that float upon the surface.

n. The Lone Wreck, from The Tides by English composer William Baines, is a dramatic tone poem which paints a haunting picture of an abandoned ship deep in the ocean, complete with the calls of sea birds.

Night gondola in Venice, Italy

The Barcarolle, or “boat song”, inspired by the songs of Venetian gondoliers, seeks to portray the rocking motion of the sea and the rise and fall of waves. Chopin’s Barcarolle is perhaps the most famous work in this genre. Mendelssohn’s Venetian Gondolier’s Song in f-sharp minor from his Songs Without Words is dark and atmospheric, suggesting nighttime on the Venetian lagoon.

Liszt was also adept at portraying the motion of the ocean. In his Legende No. 2, St. Francis of Paola walking on the waves, the waters roll and bubble beneath the saint’s feet as he crosses the Straits of Messina.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Britten transports us to more serene waters in Sailing from his Holiday Diary suite. The wind gets up in the middle section, tossing the boat about, before calm is restored.

Transcending Tunes of Light and Shade Handel: Messiah

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

George Frideric Handel © portlandhandelsociety.org

The reasons for this tradition are somewhat apocryphal: one version is that at the first London performance in 1743, the audience “together with the King”, were so moved by the ‘Hallelujah’ Chorus that they spontaneously rose to their feet. An alternative explanation is that King George II was so tone-deaf that he thought the performance had finished, and the orchestra was playing the National Anthem: once the King stood, everyone present was obliged to stand too. Whatever the reason, there is something really special about standing for such an uplifting and triumphant piece of music.

For me ‘Messiah’ will forever be associated with the beginning of the Christmas season. When I was at school, it formed an integral part of the concert which ended the Autumn term, along with the service of nine lessons and carols at the church next door to my school. I must have sung Handel’s ‘Messiah’ at least 10 times, for the tradition of performing it at Christmas continued when I joined my university choir.

Background

‘Messiah’ was composed in 1741, with a text compiled by Charles Jennens from the King James Bible and the version of the Psalms included with the Book of Common Prayer. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742 and received its London premiere nearly a year later. Initially it received a modest public reception, despite Handel’s established reputation in England, where he had lived since 1712, but gradually the oratorio gained in popularity and it is now one of the best-known, much-loved and most frequently performed choral works in Western music.

The Story

The work is organised in three sections: Part 1 tells the story of the birth of Christ and includes all the familiar elements of the Christmas story. Part 2 is concerned with Christ’s passion and death, his resurrection and ascension, and ends with the joyous ‘Hallelujah’ chorus. It is this aspect of the work which makes it just as applicable for performance at Easter as well as at Christmas (in fact, its premiere in Dublin took place 19 days after Easter 1742). Part 3 returns to the theme of resurrection and represents the real core of the work as Christ’s resurrection is connected to our own redemption and sense of hope, beautifully affirmed in one of the work’s most famous arias, ‘I Know that My Redeemer Liveth’. And I suppose the best thing about ‘Messiah’ really is all the memorable ‘tunes’ – from ‘Ev’ry Valley Shall be Exalted’ to ‘The Trumpet Shall Sound’, ‘I Know My Redeemer Liveth’ to the charming duet between tenor and alto ‘O Death Where is Thy Sting’. Then there are the choruses: ‘And the Glory of the Lord’, ‘All We Like Sheep’, ‘For Unto Us a Child is Born, ‘Hallelujah’, and the wonderful fugue of the final chorus. In between all this are some beautiful solos, recitatives, which serve to move the narrative forward, and delightful orchestral interludes.

Handel brings the text to life with light and shade, storms and sunshine, fugue and counterpoint, and a huge variety of textures and “word painting”, the technique of having the melody mimic the literal meaning of the libretto. Because of the skilful way in which Handel organises the material, and the universal, redemptive message of the text, Messiah remains a work which is uplifting and life-affirming, regardless of how it is performed.