Adolphe Charles Adam ; 24 July 1803 – 3 May 1856) was a French composer, teacher and music critic. A prolific composer for the theatre, he is best known today for his ballets Giselle (1841) and Le corsaire (1856), his operas Le postillon de Lonjumeau (1836) and Si j'étais roi (1852) and his Christmas carol "Minuit, chrétiens!" (Midnight, Christians, 1844, known in English as "O Holy Night").

Adam was the son of a well-known composer and pianist, but his father did not wish him to pursue a musical career. Adam defied his father, and his many operas and ballets earned him a good living until he lost all his money in 1848 in a disastrous bid to open a new opera house in Paris in competition with the Opéra and Opéra-Comique. He recovered, and extended his activities to journalism and teaching. He was appointed as a professor at the Paris Conservatoire, France's principal music academy.

Together with his older contemporary Daniel Auber and his teacher Adrien Boieldieu, Adam is credited with creating the later Romantic French form of opera.

Life and career

Adam was born in Paris on 24 July 1803, the elder of the two children, both sons, of (Jean) Louis Adam and his third wife, Élisa, née Coste. She was the daughter of a prominent physician, and was a former pupil of her husband, a well-known composer, pianist and professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Louis Adam gave his son lessons, but the boy was reluctant to learn even the basics of musical theory, and instead played fluently by ear:

I loved music, but I didn't want to learn it. I would sit quiet for hours, listening to my father play the piano, and as soon as I was alone I tapped on the instrument without knowing my notes. I knew without realising it how to find the harmonies. I didn't want to do scales or read music; I always improvised.

He later said that he never became a fluent sight-reader of a score. His mother concluded that her son needed a rigorous education, and he was sent to a boarding school, the Hix institute in the Champs-Élysées. It had a high reputation both academically and musically: his elder contemporary (and pupil of Louis Adam) Ferdinand Hérold had been educated there, and the music master was Henry Lemoine, another of Louis' former students. Adolphe was not an academic child, and recalled in his memoirs how he had recoiled from the study of Latin, which he found "barbaric". The fall of the French Empire in 1814–15, and the ensuing economic problems badly affected Louis Adam's income, and to save money his son was sent to a less expensive school. The staff there were capable, but Adam remained as indifferent to musical theory as to Latin.

At the age of 17 Adam enrolled at the Conservatoire, where he studied the organ with François Benoist, counterpoint with Anton Reicha and composition with Adrien Boieldieu. Adam's biographer Elizabeth Forbes calls Boieldieu the chief architect of Adam's musical development. He set his student exercises that taught him to compose sustained melodies without showy modulations and other technical devices.Adam's father did not want his son to become a professional composer: he would have preferred him to pursue a commercial or academic career, and although he gave Adam board and lodging he refused to subsidise any musical activities. By the age of 20 Adam was contributing songs to the Paris vaudeville theatres, writing what he later called "bad romances and worse piano pieces", and giving music lessons.

Duchaume, timpanist and chorus master of the new Théâtre du Gymnase, offered Adam an unpaid post playing the triangle in the orchestra. Adam said that as he would have paid to be allowed to join he was happy to serve without a salary, but he was quickly promoted to a well paid position:

My entry to the Gymnase was an event in my life. I made acquaintances and friendships with actors and writers; that was, in a word, my starting point. Duchaume died, and I succeeded him as timpanist and chorus master, at a salary of six hundred francs a year. It was a fortune. I no longer gave thirty-sous lessons, and I wrote a little less trashy music.

In 1824 Adam entered the Conservatoire's most important musical competition, the Prix de Rome. He gained an honourable mention, and the following year, at his second attempt, he won the second prize. Forbes writes that Adam derived more benefit from helping Boieldieu with the preparation of his opera La Dame blanche, produced at the Opéra-Comique in December 1825. Adam's piano transcriptions of themes from the opera were published in 1826 and made him enough money to tour the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland in summer 1826 with a family friend, Sébastien Guillié. In Geneva he met the librettist Eugène Scribe, with whom he later collaborated on nine stage works.

During 1824–1827 Adam wrote or arranged the music for several one-act vaudevilles given at the Gymnase and the Théâtre du Vaudeville, including four written by Scribe as sole or co-author. In late 1827 Scribe provided the text for Adam's first opera, a one-act comic piece, Le Mal du pays, ou La Batelière de Brientz (Homesickness, or the Bargewoman of Brientz), comprising an overture and eleven numbers; it was produced at the Gymnase on 28 December 1827. A little over a year later, in February 1829, Adam's second one-act opera, Pierre et Catherine was given in a double bill at the Opéra-Comique with Auber and Scribe's La Fiancée, and ran for more than 80 performances.

Seven months after the premiere of Pierre et Catherine Adam married Sara Lescot, a member of the chorus at the Vaudeville. Adam's biographer Arthur Pougin describes the marriage as "an important and unfortunate event for him".By Pougin's account, Lescot manoeuvred Adam into marriage, and on his side – and later hers also – it was a loveless union; they separated in 1835. Their only child, Léopold-Adrien, born in 1832, killed himself in 1851.

Adam's first full length operas were premiered in 1829: Le jeune propriétaire et le vieux fermier and Danilowa, opéras comiques given at the Théâtre des Nouveautés and the Opéra-Comique respectively. Danilowa ran well until Parisian life was disrupted by the July Revolution. That, and an outbreak of cholera, led Adam to move to London; this was at the suggestion of his brother-in-law, Pierre François Laporte, manager of the King's Theatre, Haymarket. In 1832 Laporte leased the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and in October, as an afterpiece to The Merchant of Venice, he presented James Planché's His First Campaign, a "Military Spectacle" about the Duke of Marlborough, with music by Adam. The piece was received with "loud and general plaudits", but The Dark Diamond, a historical melodrama in three acts, which followed on 5 November, failed to repeat its success, and Adam went home to Paris in December. He returned briefly to London when his ballet Faust was presented at the King's Theatre in February and March 1833.

In 1834 Adam had one of his greatest popular successes with Le chalet, at the Opéra-Comique. This was a one-act opéra comique with words by Scribe and Mélesville based on Goethe's Jery und Bätely. It was given more than 1000 times in Paris over the next four decades. In May 1836 Adam was appointed as a chevalier of the Legion of Honour, later promoted to officer of the order. His first work for the Paris Opéra was a ballet, La fille du Danube, introduced by Marie Taglioni in September 1836.Within days of the premiere of that piece, his three-act opéra comique Le postillon de Lonjumeau opened successfully at the Opéra-Comique. It was the composer's greatest operatic success internationally, quickly taken up by foreign managements and seen in London in 1837 and New York in 1840.

During 1838 and 1839 Adam composed the music for Les Mohicans, a ballet for the Opéra, and four operas for the Opéra-Comique, and in September 1839 he left Paris for St Petersburg. His ballet for Taglioni, L'Écumeur de mer (The Pirate) was given before the imperial court in February 1840, and two of his operas were staged. He left Russia for Paris at the end of March, stopping off in Berlin, where he wrote an opera-ballet, Die Hamadryaden (The Tree Nymphs), which he conducted at the Court Opera in April 1840.

Adam's next substantial work was the composition by which he has become best known: the ballet Giselle. Based on Heinrich Heine's version of an old tale, the ballet premiered at the Opéra on 28 June 1841 with Carlotta Grisi in the title role. Adam continued his prolific output, including his first grand opera, Richard en Palestine, which was produced at the Opéra in 1844 but aroused little interest. In that year he was elected to membership of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Financial disaster

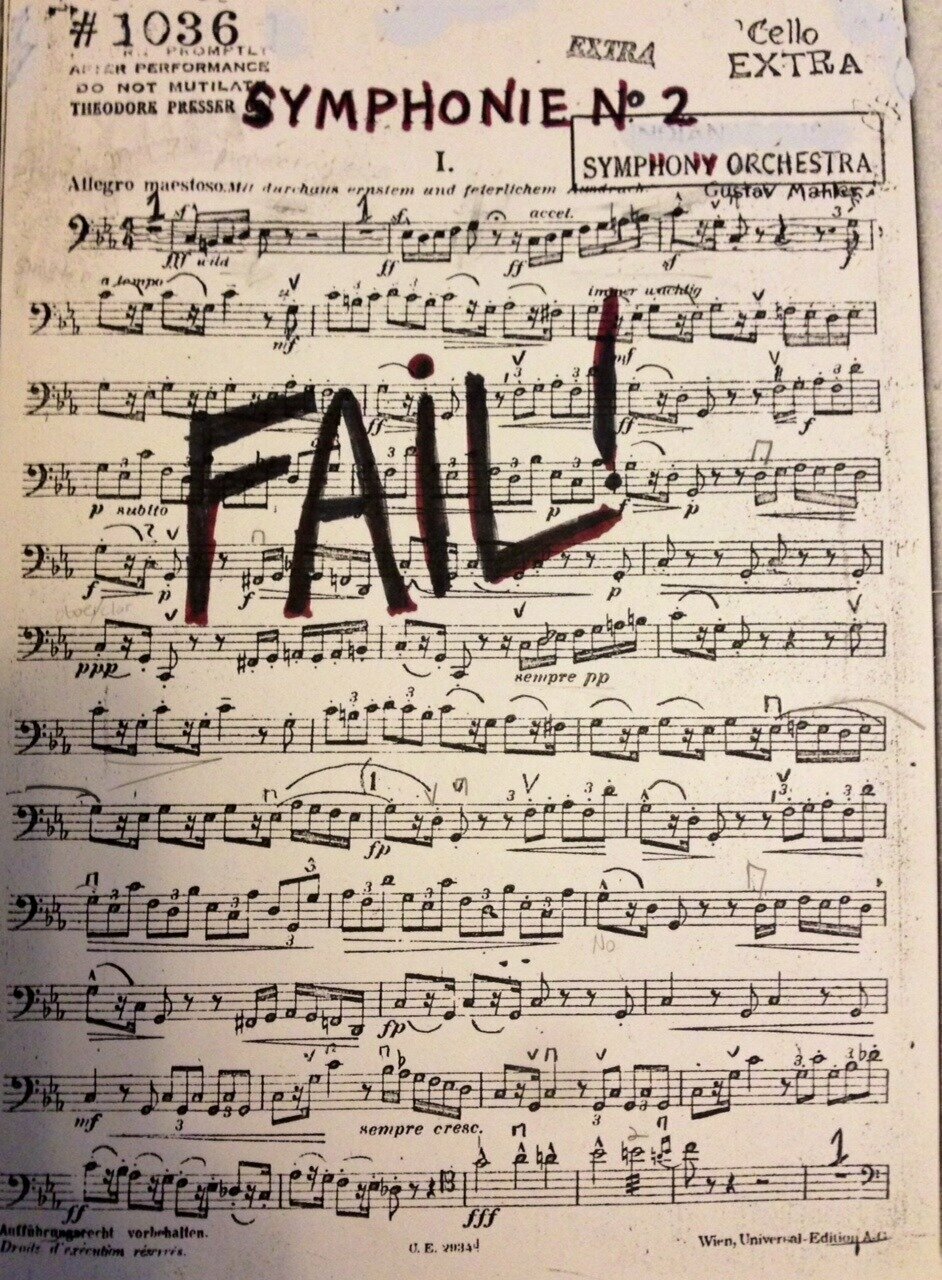

In 1845 François-Louis Crosnier, director of the Opéra-Comique, resigned and was succeeded by Alexandre Basset. Basset soon fell out with Adam and told him that as long as he was director, Adam's works would never be performed at the Opéra-Comique.[Early in 1847 a theatre in the Boulevard du Temple became available, and Adam, in partnership with the actor Achille Mirecour, took it over, rechristening it the Opéra-National. The cost of refurbishing the theatre was enormous, and in addition to investing his own money, Adam raised large sums in loans. The new opera house opened in November 1847, but from the outset its prospects looked doubtful. Financial and artistic performance alike were poor, and the 1848 Revolution was the final blow to the enterprise. The theatres were closed by the incoming régime, and when they were permitted to re-open, there was little demand for tickets at Adam's opera house, which closed on 28 March 1848, after the production of nine operas during its four months of existence, leaving him financially ruined.

Adam assigned the royalties from his earlier works to help pay off his debts, and like many other French composers in need of money he turned to journalism to earn extra income. He contributed reviews and articles to Le Constitutionnel and the Assemblée nationale. He also became a teacher, accepting the post of professor of composition at the Conservatoire, where his students included Léo Delibes.Meanwhile, Basset having left the Opéra-Comique at the time of the revolution, Adam was able to return to what Forbes calls his spiritual home under its new director, Émile Perrin.

Last years

In July 1850 Giralda, ou La nouvelle psyché – one of Adam's best operas in Forbes's view – was given at the Opéra-Comique. In 1851 his estranged wife died, and Adam married the singer Chérie-Louise Couraud (1817–1880), with whom he lived for his remaining years.For the Théâtre-Lyrique, the revived incarnation of his failed Opéra-National, Adam wrote the successful Si j'étais roi, first given in September 1852. In that year he produced six new works, enabling him to clear all his debts.

During the last three years of his life Adam continued to compose prolifically. His late works include what Forbes rates as one of his finest ballets, Le Corsaire, based on a poem by Byron; it was presented at the Opéra in January 1856, after a year's preparation. His final stage work, the one-act opérette Les Pantins de Violette (Violette's Puppets) was given at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens on 29 April 1856. Four nights later Adam died in his sleep, at the age of 52. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery.

In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Forbes writes that much of Adam's prolific output was ephemeral. This includes the many popular numbers he wrote for vaudevilles in his early years, a large number of piano arrangements, transcriptions and potpourris of favourite operatic arias, and numerous light songs and ballads. Nonetheless, "there remain several operas and ballets that are not merely delightful examples of their kind, but are also scores full of genuine inspiration". In this category Forbes includes Le chalet (which incorporates music from the cantata he wrote for the 1825 Prix de Rome competition) which she ranks with Adam's best works for its freshness of invention. For the musicologist Theodore Baker, Adam ranks with Auber and Boieldieu as one of the creators of French opera, thanks to the expressive power of his melodic material and his keen sense of dramatic development.

In France, during Adam's lifetime and beyond, Le chalet was his most popular opera. In other countries the favourite was Le postillon de Lonjumeau. In Germany in particular the opera was celebrated for its tenor aria "Mes amis, écoutez l'histoire" (given in translation as "Freunde, vernehmet die Geschichte"), with its demanding high D. Grove comments that the opera has distinctive and well characterised roles and a sense of theatre, found in all Adam's operas. Of the later operas, Grove singles out Giralda and Si j'étais roi as "the most stylish, tuneful and accomplished".

Although he was a prolific composer of opera, Adam wrote ballet music even more fluently. He commented that it was fun, rather than work. Giselle is the best known; Baker calls it a major work in the history of choreography, which continues to be performed with the same success. Forbes comments that although Giselle has the advantage of a particularly memorable plot, La jolie fille de Gand, La filleule des fées and Le corsaire are of equal quality musically.

Little of Adam's religious music has entered the regular repertory, with the exception of his Cantique de Noël, "Minuit, chrétiens!", known in English as "O Holy Night".

Adam's memoirs were published posthumously, in two volumes: Souvenirs d'un musicien (1857) and Derniers souvenirs d'un musicien (1859).